Best Education Articles of 2019: Our 19 Most Popular Stories About Students and Schools This Year

By Steve Snyder | December 17, 2019

This is the latest roundup in our “Best Of” series, spotlighting top highlights from this year’s coverage as well as the most popular articles we’ve published each month. See more of the standouts from across 2019 right here. (You can get all the latest features, essays and videos delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for The 74 Newsletter)

From Minneapolis to Memphis to Puerto Rico, from sexual assault investigations to civics education breakthroughs to academic profiles, it was an eclectic year here at The 74, featuring a wide array of both breaking news coverage and big-picture profiles. And that doesn’t even touch on our exclusive Brown v. Board microsite that looked to restore the unsung heroes to the story behind the landmark desegregation verdict.

As we always do in December, we thought we’d take a beat before diving into yet another presidential election to put a final stamp on the year that was. Below, we’ve assembled the 19 most popular and most widely discussed articles from 2019 (you can also check out our top 18 articles from 2018).

Civics Education: American democracy is in trouble — just ask a poll worker. We vote less often than other developed nations, our rates of volunteering have plummeted, and less than half of us could pass a citizenship test. Perhaps that’s why political scientists cheered when a recent study found that alumni of Democracy Prep Public Schools vote at much higher rates than their peers. Students at the schools study social change and debate current events; even more strikingly, they complete an impressive array of civics-centered requirements to graduate — from writing policy briefs to petitioning lawmakers. The network’s founder, Seth Andrew, says Democracy Prep is doing work that should be replicated across the country. “I think every school should have a civic purpose. Ours is just more explicit about it than most.” This past spring, The 74 published a four-part series and a documentary on the school network, orchestrated by writer Kevin Mahnken and editor Andrew Brownstein. The effort launched with this profile of the network and its founder, taking a closer look at the role education plays in curbing our civic ignorance and polarized politics. (Read the full longread from reporter Kevin Mahnken)

Also, be sure to check out these other chapters in our Democracy Prep series:

● How Democracy Prep Is Drawing Upon Civics to Challenge Its Students to ‘Change the World’ — Before They Graduate (Read more)

● Democracy Prep’s Expansion Woes Raise Questions About Whether Civics Education Can Be Brought to Scale (Read more)

● Can Civics Education Allow Schools to Rediscover Their Democratic Purpose — and Help Rescue America From Decline? (Read more)

● WATCH: Inside the Civics-Driven Democracy Prep, Students Are Embracing Their Assignments to ‘Change the World’ (Watch the full video)

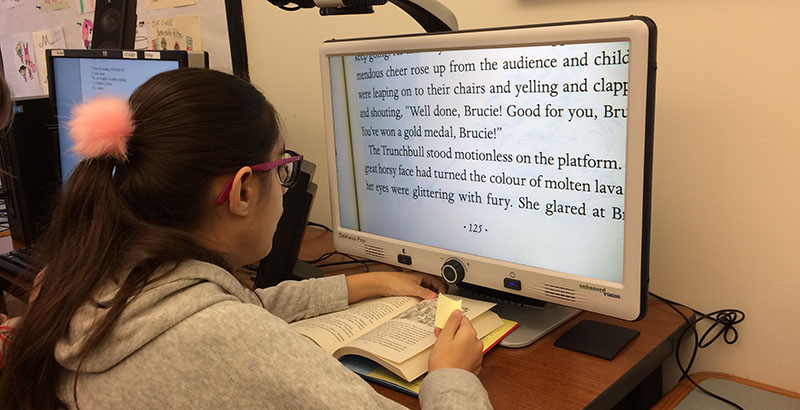

Special Education: Sophia Salehi is blind, until recently unable to navigate the hallways at school, let alone her neighborhood. Her parents tried for 11 years to get her Houston-area schools to provide the special education services she was entitled to. But not even a series of court victories convinced officials to budge. She now goes to school in Massachusetts. Jaivyn Mauldin reads in the 99th percentile, but his severe dysgraphia means he can’t write. His Austin-area schools said he was too smart for special education and assigned him handwriting drills as discipline. His family moved to Oregon to get him help. Angela Smith was a special education evaluator in Dallas — who couldn’t get her own son evaluated. When the U.S. Education Department confirmed a 2016 bombshell report by the Houston Chronicle, disability advocates and parents learned, to their shock, that Texas had secretly placed an illegal cap 12 years before on the number of children with disabilities who could get special education services in schools. An estimated 250,000 students were languishing, unable to get the help they were entitled to. Orders from Washington notwithstanding, today — three years after the nation’s second-largest state pledged to reverse course — advocates say precious little has changed. And if Texas can get away with defying federal law, what’s to stop other states from following suit? (Read the full feature from national correspondent Beth Hawkins)

Exclusive: Sixty-five years ago, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in America’s public schools was unconstitutional. This past May, we launched a new website and oral history commemorating the anniversary: The Untold Stories of Brown v. Board, a multimedia deep dive into the lesser-known students, parents and plaintiffs who joined forces six decades ago to wage the legal battle against “separate but equal.”

A brief overview of the project, which can now be found in full at The74Million.org/Brown65: In the American judicial system, the two small words “et al.,” meaning “and others,” erase the names, faces and histories of everyday individuals seeking remedies for wrongs done to them. Used as a reference in class-action litigation in place of the names of each individual plaintiff, those four letters relegate men, women and children to what can be characterized as a “legal wasteland,” rendering them and their stories unknown. In the instance of Oliver Brown, et al. v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, those four letters diminished the stories of families who participated in five essential class-action lawsuits across the nation. Those five suits — Oliver Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Briggs v. Elliott, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart and Bolling v. Sharpe — were later consolidated by the United States Supreme Court.

Although the name Oliver Brown is universally known, the names and stories of these other revolutionaries have remained largely unknown and untold, buried under the weight of four little letters. But now, for the first time, a wide swath of Brown v. Board plaintiffs and their relatives assembled by Cheryl Brown Henderson, founding president of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research and daughter of Oliver Brown, is working on changing that — by detailing their stories of oppression, their battle for justice and their triumph. She has assembled a new book, Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, and we have been thrilled to be the digital launch partner in sharing their narrative. Read all the excerpts, watch the video testimonials, learn more about the legal history and download the book. Visit our special microsite: The74Million.org/Brown65.

Investigation: On Sept. 23, 2015, a 5-year-old boy with disabilities in Detroit arrived home from school bruised and very likely sexually assaulted. The school bus driver, who told the boy’s mother about probable sexual misconduct by other students, didn’t report it to the district. And though she informed school officials about the incident the following day, administrators didn’t investigate, or speak with the boy’s family, for months. A federal probe that concluded last year determined that this case may be just one sign of larger problems with how Detroit Public Schools deals with sexual misconduct — and the district is not alone.

While most of the debate around Title IX, which requires schools to address sexual violence, has focused on whether colleges provide due process for accused students, the Trump administration has quietly discovered that many K-12 school districts had no plan to deal with these cases — a violation of federal law. In cities including Detroit, Kalamazoo and Washington, D.C., officials found that districts had little to no Title IX training — and some had policies explicitly barring investigations of sexual assault reports from taking place. Through Freedom of Information Act requests, The 74 has exclusively obtained records that provide the first look at how the Trump administration has enforced Title IX in investigations of schools, revealing that at least 70 districts and colleges had to overhaul their policies to address problems uncovered by the government in the past two years. (Examine the original documents and read Tyler Kingkade’s full report here)

Mastery-Based Learning: As more schools consider adopting innovative models like project-based or experiential learning, educators are realizing that the broad set of skills students are learning don’t translate easily into letter grades or GPAs. That becomes a problem when it comes time to submit transcripts for college admissions. So D. Scott Looney, head of Cleveland’s private Hawken School, decided to launch a group to design a different kind of high school transcript. After two years of development, the Mastery Transcript Consortium now has 250 member schools, and a few of them will be submitting this new transcript to colleges for the first time in the 2019-20 academic year. The transcript is still being tested and discussed among member schools, but it’s drawn attention and headlines for its nontraditional approach of visually describing student learning. The group, which includes a large proportion of private schools, has also been at the center of debates around equity in college admissions. Does eliminating grades in favor of more holistic descriptors improve or exacerbate inequality? (Read the full feature from Kate Stringer)

College Success: Not that long ago, many Houston Independent School District high schools lacked what’s known as a school profile — essential information to college admissions officers wanting to know a school’s demographics, AP offerings and SAT/ACT scores. “That’s the basic document colleges use to gauge a student in relation to other students. Many of our campuses refused to do it. They just didn’t see a need, because for years they had never had a kid apply to a non-local option,” said former fifth-grade teacher Rick Cruz. That mindset began to change after Cruz and some Houston ISD colleagues in 2010 formed EMERGE, a program meant to mirror what private college consultants do for the wealthy but tailored to the specific needs of Houston ISD’s first-generation, low-income students. The goal was to match those students with colleges that offered full-ride scholarships to high-achieving, high-poverty students, make sure they run the necessary application gauntlet and then track them once they enroll. Thanks to district and philanthropic support, EMERGE is now in every Houston ISD high school and the results are strong: 95 percent of EMERGE students have either earned college degrees or are on track to, more than 80 percent have a 3.0 GPA or better, and 87 percent are expected to earn a bachelor’s in four years. (Read Richard Whitmire’s article)

● Other Excerpts from ‘The B.A. Breakthrough’: Houston’s college counseling experiment was just one in a series of special features tied to the new book we published in 2019 — Richard Whitmire’s The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See notable excerpts and profiles, and download the complete book, at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

Personalized Learning: When children go to the doctor, they receive an individualized plan to support their health. Why isn’t this the case in education? A new report from Harvard’s Education Redesign Lab asks this question and seeks to upend the “factory model” style of education that provides all students with very similar academic career tracks. Instead, the report says, every student should have an individualized success plan that recommends key services to support his or her specific needs, whether it’s math tutoring, mental health counseling or speech therapy. This requires a big lift in organization and resources — but this effort should not be limited to schools, the report says. Here’s why the whole community needs to be involved in supporting the whole child — and 10 guidelines for crafting success plans that support children from birth through college. (Read the full feature from Kate Stringer)

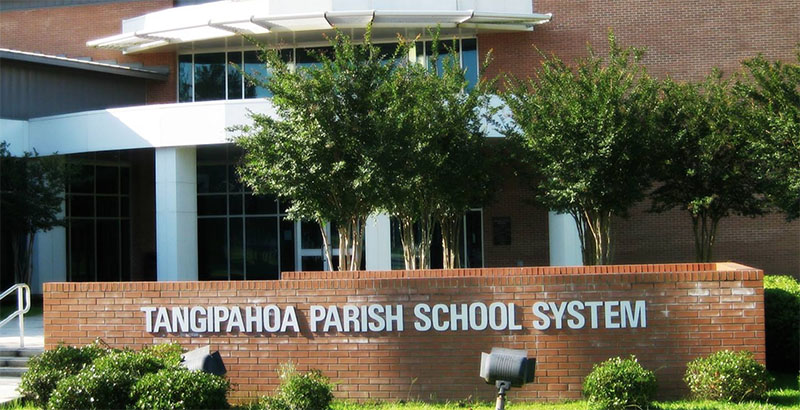

Desegregation: In the years after Brown v. Board of Education, the United States entered a contract with its black citizens: Their children would no longer be consigned to separate, inferior schools, and if districts attempted to keep them out, they would have their day in court. Hundreds of cases were filed, petitioning judges to break down barriers between black and white students in school assignments, facilities, learning materials and budgets. One was triggered in 1965 in southeastern Louisiana’s little-known Tangipahoa Parish, where a local truck driver and father of 15 sued the local school board for providing black students with a substandard education. The children of Tangipahoa not only got their day in court — since the day the case was filed, they’ve received the equivalent of roughly 20,000 days. We may now be nearing the last, as both sides in Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board have asked a federal judge to approve an extensive settlement in one of the longest-running desegregation cases in the country. Kevin Mahnken reports on the history of the case, and what awaits. (Read more about the history of the case, and what awaits, from Kevin Mahnken)

74 Interview: Gloria Ladson-Billings remembers the first time she learned that an African American could graduate from Harvard University: She was in Ethel Benn’s fifth-grade class in Philadelphia. That realization — and Benn’s excellent teaching — set her on a path to find out what makes a great teacher. Since the 1990s, Ladson-Billings has been studying and writing about culturally relevant teaching and what it takes to successfully educate all students, especially the children of color so often left behind. At the core of her educational philosophy are three components of culturally responsive education: academic success, cultural competence and sociopolitical consciousness. Teachers must accept responsibility for bringing all three into their classrooms, she says. Ladson-Billings spoke to The 74 about how teachers can talk to students about current events, the difference between integration and desegregation, and the hallmarks of being a culturally relevant teacher. (Read the full interview from Laura Fay)

Social-Emotional Learning: It took two years of collaboration among 200 teachers, students, parents, scientists and policymakers, but a new report on bolstering social-emotional learning in America’s schools has been published. In From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope, these SEL experts, convened by the Aspen Institute, share six ways that teaching skills like collaborating with peers, managing emotions and feeling empathy can help children be better students and citizens of the world. Research has shown how teaching these skills can improve academics, graduation rates and earnings — and the report provides a concrete path toward integrating social-emotional learning in schools. From improving teacher prep programs to lifting up student voice and choice, here are the big ideas coming out of the group’s collaborative work. (Read the full story from Kate Stringer)

Profile: What do you do about a school that’s adored by its families but failing academically? Do you start fresh and risk upending the community that made the school beloved in the first place? At Dugsi Academy in St. Paul, Minnesota, the answer was a resounding no. A haven for Somali immigrant families, the charter school was required by its authorizer to turn itself around or shut down — and today, nearly two years into what school turnaround veteran Mary Stafford calls “Extreme Makeover: The School Edition,” her plan for keeping the elements Dugsi’s families valued while changing what wasn’t working is showing signs of promise. (Read more about Beth Hawkins’s memorable visit to the school)

Puerto Rico: Days after Julia Keleher announced her resignation as Puerto Rico’s education secretary, she stepped up to a microphone at a Yale University conference and spoke of her defiant and sometimes bitter crusade to change the island’s entrenched culture of corruption. That effort, she said, created “armies of people that literally would have been happy to take my head off.” But even then, her work was being scrutinized by another set of observers with the power to turn that narrative on its head: the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In July, Keleher and five others were indicted in an alleged conspiracy to direct more than $15 million in federal funds to organizations with personal and political connections. All pleaded not guilty. But Keleher’s indictment surfaces a deeper irony. Years before becoming education secretary, she worked on a U.S. Department of Education team tasked with fixing waste, fraud and mismanagement of federal funds in Puerto Rico’s school system — issues that had led to the conviction of an education secretary nearly two decades earlier. This alleged role reversal is one of many lingering riddles to have emerged since her arrest. Friends and colleagues describe Keleher as a tireless advocate known for 2 a.m. emails and sometimes little sympathy for those lacking her single-minded work ethic. But they also recall her as someone too smart to cut corners and too tough to get ensnared in someone else’s scheme. In this special 74 investigation, we take an expansive look at Keleher’s decades-long career as a hard-nosed change agent intent on ending corruption in Puerto Rico — and an indictment that is calling that narrative into question. (Read Mark Keierleber’s profile)

Opportunity Youth: For Dionna Camino, it was caring for her terminally ill father. For Shelby Morales, it was an unexpected pregnancy at age 14. For both, it was too much responsibility too soon that knocked them off the tightrope of getting through high school and college to land a good-paying job. Now, they are among the estimated 4.5 million so-called opportunity youth nationwide — 16- to 24-year-olds who are neither in school nor working — struggling to put their lives back together. Disengaged from both education and the labor force, these young people are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, too often finding themselves in the school-to-prison pipeline. Some are homeless or have young children. Maybe they dropped out of high school, have criminal records or are on probation. But some have high school diplomas and even some college coursework. For most opportunity youth, it isn’t a defined set of missteps; rather, it’s a churning sea of relentless waves and undertows pushing them under and dragging them in all directions. They can look up and see the school-to-success high wire — options and resources available to teens that will guide them toward becoming financially, emotionally, socially secure adults. They just don’t know how to climb back on. Bekah McNeel reports on the steps cities around the country are taking to help. (Read the full story)

A Manhattan High School Reframes How Slavery Is Taught Using The New York Times’s 1619 Project

Curriculum: Over years of classes, 11th-grader Jeremias Mata had viewed slavery with a certain simplicity and hopelessness — that many black people had once been slaves and that was that. This year, learning about slavery has been different for students at Manhattan’s Facing History School, partly because teachers are incorporating The New York Times’s 1619 Project — a compilation of essays and poetry that re-examines slavery’s legacy in the U.S. 400 years after the first enslaved people arrived here from West Africa. The project is helping schools nationwide reframe how slavery is taught in a way that captures its brutality, complexity and influence in shaping America, while also affirming the experience as integral to black Americans’ identity and their contributions to the country. This reframing is “extremely important, especially with the student body that we teach here,” says history teacher Eric Albino. New York City is a predominantly black and Hispanic district that struggles with inequity and segregation. Teaching curriculum that is relevant to the experiences and perspectives of students of color has been a major — if not universally embraced — policy push of New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, though the practice isn’t mandated across the country’s largest school system. (Read more about Taylor Swaak’s visit to see the 1619 Project in action)

Eating, Shopping and Project-Based Learning: A View From Memphis’s Mall-Based Crosstown High

Profile: One semester into the inaugural year at Memphis’s Crosstown High School, a project-based-learning charter school and recipient of a grant from the folks who run the XQ high school redesign contest, leaders are learning some important lessons. Not all projects catch students’ attention. Freshmen coming from years in a traditional school setting aren’t quite ready to totally guide their own learning. It’s hard to teach and test math in nontraditional ways. And given access to the unique mall setting that houses the school, teens will be teens. This past February, we reported on the school’s unique curriculum and setting, and its leaders’ goal of attracting a diverse student body. (Read Carolyn Phenicie’s full profile of the school)

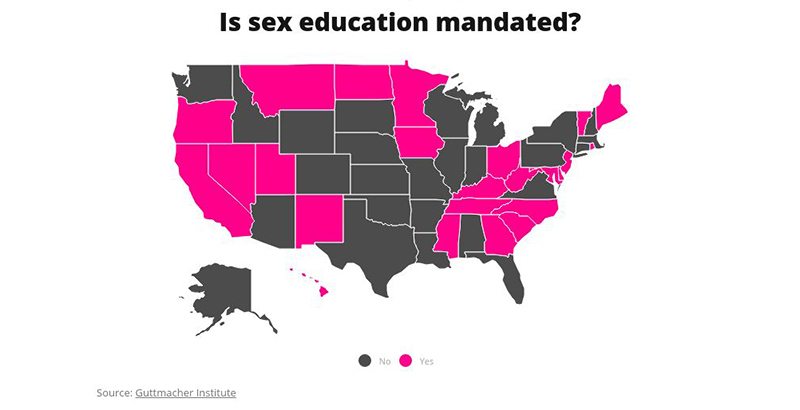

Sex Education: Students, advocates and lawmakers across the country are re-examining the role of sex education through the lens of the #MeToo movement. A new study shows that learning refusal skills can protect students from later sexual assaults, which researchers say indicates that improving sex ed should be the next step for the #MeToo movement — a way to both protect students from being victimized and prevent them from perpetrating assaults. A historian who studies sex ed called the results “hugely significant,” and the researchers themselves said the study could change how adults think about teen sex and sex education. The study found that most students who had learned refusal skills had also received comprehensive sex education in school. As the #MeToo movement takes hold, some state lawmakers have taken steps to add consent and healthy relationships to their schools’ sex education classes and generally make the programs more comprehensive. Advocates applaud the changes, but some parent groups and critics have pushed back against lessons they say are not age-appropriate and policies that minimize local control. (Read the full story from Laura Fay)

Inspiring: It would have been a long-shot bet that twin brothers who spent their childhoods struggling with a rare speech impediment and toiling in the fields as immigrant farmworkers would one day become international academic stars. But Octavio and Omar Viramontes, who recently graduated one day apart from top medical schools, had a secret weapon: the perseverance of their parents, who brought the family from Mexico in search of a better life. From them, the twins learned the importance of hard work and gained a firm belief in the power of education. And now, having been high school valedictorians and racked up scholarships and academic honors, Dr. Octavio and Dr. Omar are preparing to give back to their community. (Read more about this inspiring story from Debra West)

Deeper Learning: Since 2017, humanities students at High Tech High Chula Vista, a San Diego-area charter school, have been holding human lives in their hands: Each year, they assist attorneys at the California Innocence Project who are considering which pleas to review from prisoners who maintain they’re innocent. The idea for the project comes from an approach to education called “playing the whole game,” which suggests that students learn best through real work that resembles what they will likely encounter outside of school. It’s the brainchild of Harvard Graduate School of Education professor emeritus David Perkins, who conceived it after thinking about the most meaningful experiences he had in high school: drama, music, science fairs and the like. These and other large-scale endeavors, he said, “seemed more meaningful” than the rest of the curriculum. But whether this approach helps students see the bigger picture or simply flounder by “sharing their ignorance” of complex topics remains an open question. (Read the full story from Greg Toppo)

Future of Work: With a bachelor’s degree in psychology, 22-year-old Rachel Van Dyks expected to easily land a good job. Instead, the 2017 graduate works 46 hours per week at a local ice cream parlor and a high-end steakhouse — while earning an associate’s degree at a for-profit technical school. She’s not alone; while a majority of college graduates require additional education to qualify for a good-paying job, many don’t find that out until after commencement exercises are over. The traditional path is to pursue a master’s degree, but 14 percent of college graduates, like Van Dyks, are abandoning the academic track and enrolling at a community college or a for-profit technical school and getting an associate’s degree or industry certification, specifically to qualify for a job. (Read the full story from Laura McKenna)

Integration: Over several months this past spring, national correspondent Beth Hawkins tracked the groundbreaking integration efforts of the 78207, the zip code located on the west side of San Antonio, Texas. It is the poorest neighborhood in America’s most economically segregated city: 91 percent of students in the San Antonio Independent School District are Latino, 6 percent are black, and 93 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. As Beth reports, into this divided landscape three years ago came a new schools chief, Pedro Martinez, with a mandate to break down the centuries-old economic isolation that has its heart in the 78207. In response, Martinez launched one of America’s most innovative and data-informed school integration experiments.

He started with a novel approach that yielded eye-popping information: Using family income data, he created a map showing the depth of poverty on each city block and in every school in the district — a color-coded street guide comprising granular details unheard of in education. And then he started integrating schools, not by race but by income, factoring in a spectrum of additional elements, such as parents’ education levels and homelessness. To achieve the kind of integration he was looking for, he would first have to better understand the gradations of poverty in every one of his schools and what kinds of supports those student populations require, and then find a way to woo affluent families from other parts of the city to disrupt these concentrations of unmet need. Martinez’s strategy: Open new “schools of choice” with sought-after curricular models, like Montessori and dual language, and set aside a share of seats for students from more prosperous neighboring school districts, who would then sit next to a mix of students from San Antonio ISD. Read Beth’s immersive profile of the San Antonio experiment.

Go Deeper: See all of The 74’s top 2019 highlights right here. Get the latest features, essays, analyses and videos delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for The 74 Newsletter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter