Democracy Prep’s Expansion Woes Raise Questions About Whether Civics Education Can Be Brought to Scale

By Kevin Mahnken | April 10, 2019

In 2012, the lauded school network embarked on a four-state, $21.8 million growth spurt. Seven years later, it has retreated from a school in DC while campuses in Las Vegas and elsewhere face fiscal ‘austerity’

Las Vegas

“Democracy Prep at the Agassi Campus” is the kind of unwieldy name you get when one well-defined charter school absorbs another.

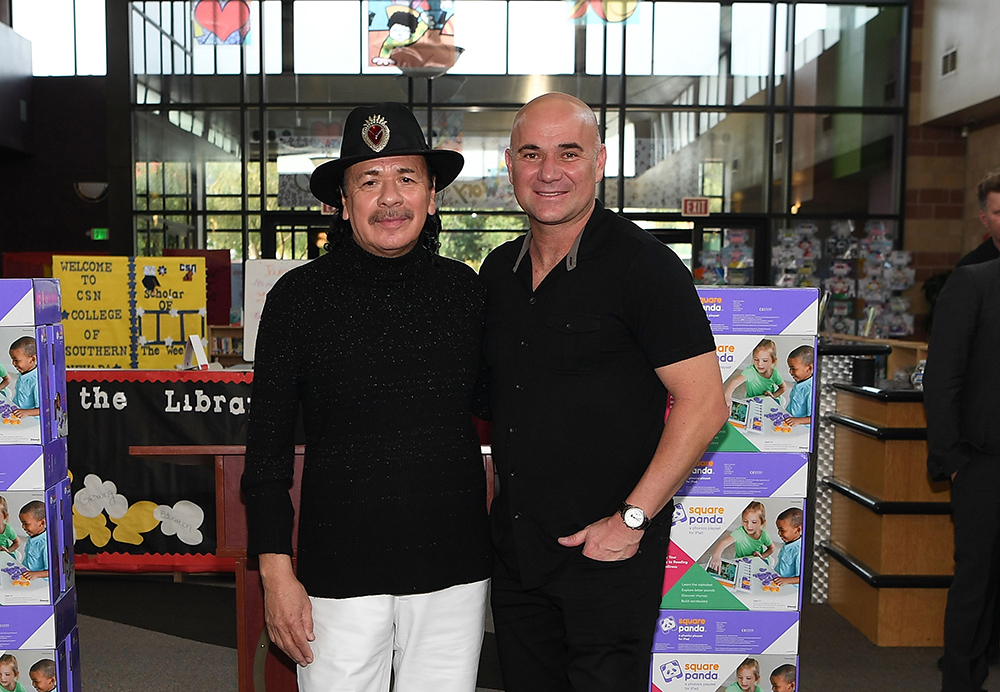

When Democracy Prep — a New York City-based charter network that focuses on preparing students for citizenship — reached an agreement to take over the flagging Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy in December 2016, it assumed more than just the academic obligations of a school that had been in operation for 15 years. It also had to absorb the identity of a community institution.

That decision has brought some benefits. The school was opened in 2001 by tennis great and native son Andre Agassi, his initial foray into what has become a second career seeding charter schools across the country. Today, it serves hundreds of predominantly black and Hispanic students from the working-class neighborhoods of west Las Vegas.

DPAC is the most impressive Democracy Prep facility anywhere in the country. In New York, the network’s schools are often forced to claw for space in buildings that house other programs. At DPAC, it takes a significant amount of walking to see every school installation, many of which are named after prominent Las Vegas brands that helped finance their construction: The MGM Mirage Building is situated near the Cirque Du Soleil Auditorium, both of which lie under the William J. Hornbuckle III bridge (named for the father of MGM Resorts International President William Hornbuckle IV).

The mammoth gym, hung with multiple state title pennants from the Agassi Prep days, still features the charter’s original logo on the basketball court. Elsewhere, from student uniforms to posters on the walls, the old heraldry has been changed to include Democracy Prep’s signature shades of blue and gold, with graduation caps soaring upward.

But school cultures don’t blend as easily as school colors.

Enrollment sank when the reconstituted DPAC opened in the fall of 2017, particularly among high schoolers. Some upperclassmen had attended Agassi Prep since kindergarten, and none were expecting a shift to an entirely different academic culture. Their families, angered by the sudden change to an unfamiliar operator, bitterly protested the move. In 2018, DPAC’s first graduating class of seniors numbered just seven, down from 31 who had started the year.

For the network, such problems are becoming more common. Now wrapping up its 13th year in operation, Democracy Prep has become a kind of test case — not just for whether a successful charter school model can be replicated, but also for whether a comprehensive focus on civics instruction can be brought to scale.

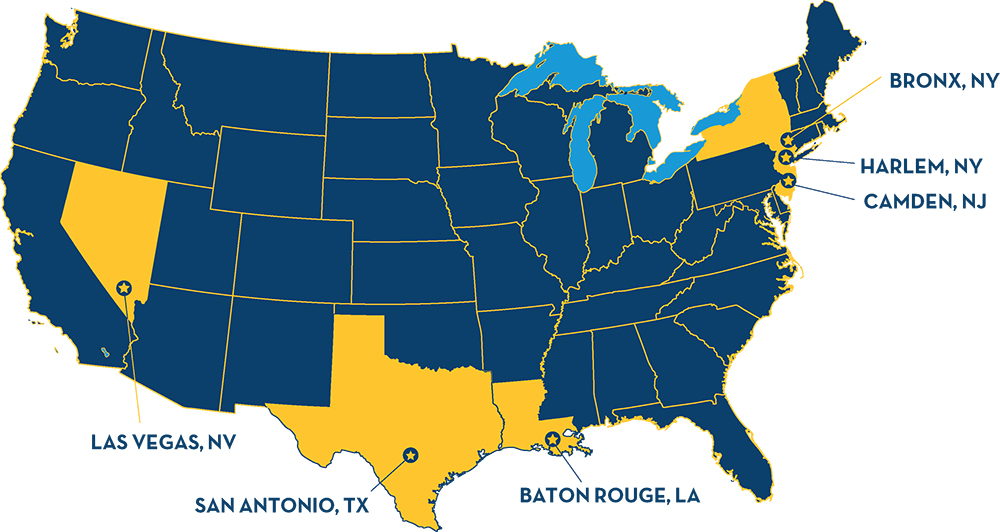

Unique among the nation’s major charter school networks, Democracy Prep places civics education at the heart of its academic mission. High schoolers study politics and sociology, completing extensive capstone projects during their senior year; younger students are pushed to discuss current events, lobby state lawmakers and take part in voter registration drives. Powered by $21.8 million in federal support, Democracy Prep has planted its flag in the District of Columbia, Baton Rouge, Las Vegas and San Antonio over the past five years. In each, it implemented its distinctive model of “no excuses” practices and heavy emphasis on democratic engagement.

Now, financial difficulties — some of them stemming from low student enrollment — have led the network to reconsider both its rapid pace of expansion and its longtime commitment to forgoing philanthropic funding. Last August, facing the prospect of a likely charter revocation in Washington, D.C., the network announced that it would pull out of the school it had operated there since 2014. And after six years in leadership, the network announced in January that CEO Katie Duffy is on a medical leave, with no set date for return.

While Democracy Prep has grown from its initial class of 130 sixth-graders in Harlem in 2006 to roughly 6,500 students in 21 schools today, its leaders concede that critical missteps have led to underperformance and parent opposition in some locations. The schools have, at times, struggled with the perception of being outsiders in their host communities, importing a New York-style approach to education reform without regard for the wishes of local families.

Natasha Trivers, the network’s interim CEO, said that some of the backlash to Democracy Prep in Las Vegas was difficult to combat because of the sheer distance between the school and the organization taking it over.

“We’ve always dealt with the haters, so to speak, but that was haters on a really large scale.” She added that she regretted “not getting out in front of our parents so that they heard our voice louder than the detractors in a way that we just haven’t experienced before.”

DPAC Executive Director Adam Johnson said that some skepticism was to be expected from disadvantaged families who had been promised educational miracles before.

“In our community, lots of folks have come in and said that they want to do these great things,” he said. “If it doesn’t live up to the billing, one time after the next, you’re like, ‘Well, is this going to happen? Is this going to be the time that it’s good?’”

To further complicate matters, faculty layoffs this year have affected at least one of the network’s signature civics programs.

As a prerequisite for graduation, all Democracy Prep seniors complete what is called a Change the World assignment — essentially a nine-month service project that requires students to identify a community problem, such as homelessness or drug abuse, and devise a plan to address it.

Each senior is assigned a faculty mentor who is meant to help keep months of research and implementation from going off-track. But after a series of layoffs at DPAC in early February, several students lost their mentors.

Earning trust: Earning trust

Johnson is working hard to earn trust. During a February visit to DPAC by The 74, he was seen greeting students by name and doling out hugs at the high school’s morning meeting. On weekends, he chaperones school visits to museums and amusement parks, and starting April 12, he will be leading a weeklong student trip to Ecuador to sightsee and perform community service. Just like the students, he’s using the online platform Duolingo to brush up on his Spanish.

Students and staff speak highly of their executive director, though he brought no school leadership experience to the job; instead, Johnson was recruited from a development role at Teach for America. A friendly if towering presence (he played forward on his college basketball team at St. Michael’s College in Vermont), he has a smile that can be contagious.

When Agassi Prep entered discussions to initiate a turnaround in 2016, it was bending to academic reality. That year, its secondary school was ranked among Nevada’s bottom 5 percent academically, and its elementary school was given two stars out of five on the state’s rating system. Though begun with great expectations, and often enjoying the beneficence of Agassi’s celebrity friends — Carlos Santana donated 200 guitars in 2013 — the school simply wasn’t educating its students up to Nevada’s standards; it would have to find a new operator, enter state receivership or close.

But the community wasn’t eager to welcome a new organization from out of town. Agassi Prep teachers wrote anonymous letters complaining that they had to reapply for their own jobs. Families balked at reports of a 10-hour school day and stricter standards on student behavior. The takeover was finalized in late 2016, though hundreds of families protested against it. The move, euphemistically termed a merger, coincided with the school becoming the first charter to join Nevada’s Achievement School District for underperforming schools.

Johnson said he was prepared to see faculty members leave; atop the annoyance of having to reapply, teachers were being asked to work a longer day and answer to a new, unfamiliar boss. But he said he “never expected” the flight of families from his newborn school in the middle of its first year.

The shift in culture, particularly around school discipline — Democracy Prep operates on a demerit system in which students can routinely be dinged for infractions like tardiness and uniform violations — likely alienated students, he said.

“One school year ago they were in the same building, in the same seats, maybe looking at the same teacher. And now that teacher’s enforcing a whole different set of rules. If you could imagine getting your mind wrapped around [that] as a child, you’d say, ‘You’re telling me I can’t do this? We literally just did this four months ago in your second-period class. Why can’t we do it now?’”

By all accounts, the turnaround was hardest on students close to graduation. Mauriyani Spell, a senior headed to Louisiana State University in the fall, said that the previous school year had been rocked by transfers and culture shock. After most of the senior class left for other high schools over the summer or after basketball season, her grades began to slip.

“I started getting depressed,” she said. “It was like this dark cloud up in the school, and nobody was happy. We were always arguing with teachers.” The problem, she believes, was that longtime students were instilled with the “Agassi mindset”; they resented the school that had displaced the one they were used to, and they didn’t appreciate Democracy Prep’s more ambitious academic mandates, such as the requirement for high schoolers to learn Korean.

“They weren’t ready for the change,” she said.

Loss of mentors: Loss of mentors

Taylor Simpson, who teaches classes in American Democracy and Sociology of Change to seniors at DPAC, said he doesn’t let the staffing changes faze him. He’s too busy focusing on atrocities.

“I’m focusing on this concept of bad things that happened in the past, and what we can learn from them in the future,” he said. “We’ve looked at Jonestown. We’ve looked at COINTELPRO. We’ve looked at the rise of the Nazi Party — not so much the history of the Nazis, but instead how people allowed this stuff to happen.”

He likes the blend of civics fundamentals and political debate at Democracy Prep, which allows him to pair a discussion of wrongful convictions — such as those of the Central Park Five and the West Memphis Three — with an examination of the rights of the accused under the U.S. Constitution.

The lessons are imaginatively designed, often incorporating acclaimed documentary films (a recent visit to the class included a screening of A Night at the Garden, an Academy Award-nominated documentary short depicting a pro-Nazi rally held at Madison Square Garden in 1939). Simpson periodically engages students in role-playing exercises around diplomacy and battlefield combat — not a stretch for him, since he deployed to both Afghanistan and Iraq as a Marine.

But the departure of several faculty members has been hard. It means that, on top of his duties leading the class, Simpson must work personally with seniors whose project mentors left the school in the last months before they graduate. Arturo Martinez, the senior class president and valedictorian, said that he appreciated Simpson as a teacher and that his Change the World project — he is studying mental health at the DPAC middle school — was leading him to consider his priorities as a citizen.

“His class is awesome,” he told The 74. “I like it because the project I’m doing — that kind of helped me not only understand what community is but helped me in what I want to become in life.”

Still, the faculty departures have evidently sunk some projects into inertia. Midway through the year, a number of students seemed indecisive about the direction they wanted their projects to take, said Arturo.

Some of his classmates have indeed developed worthy projects. One wants to appropriate some of DPAC’s ample classroom space to host a GED program for local English learners. Another dreamed up an app that would link prospective pet owners with animals to adopt. And a budding young architect is trying to design an inclusive community for adults with cognitive and developmental disabilities.

But losing their mentors has thrown up a roadblock, Simpson said, for both logistics and morale.

“It definitely does make it difficult,” he acknowledged. “My priority is that it will always be my classroom. … I have to wake up each day and still get ready to go teach. So it doesn’t really do me any justice — or better yet, doesn’t do the students any justice — for me to show up and get mad and angry and kick and scream at that.”

Whatever the staffing or enrollment challenges, the school is moving forward with its programs and making gains where it can. In February, the boys’ basketball team, coached by ex-UNLV star Trevor Diggs, was nearing the end of a 23-6 season, and students were preparing for international trips.

Walking around the Las Vegas campus today, visitors are often greeted with signs of a school entering academic and social recovery. A gold banner proclaims DPAC Middle School’s emergence as a four-star program under Nevada’s state accountability system, approaching the top tier for schools statewide. During Black History Month, students were seen role-playing the exploits of Harriet Tubman and decorating the halls with cutout Afrocentric murals. Eighth-graders were getting excited about an upcoming trip to Carson City, where they would meet the newly inaugurated governor, Steve Sisolak.

But at times, the grounds appear sparsely populated. While the Cirque du Soleil Auditorium can attain a circus-like atmosphere during lunch hours, with hundreds of students packed into a joyously chaotic mass, footsteps echo loudly off the sleek hallways and curving staircases that Andre Agassi spent millions to build.

A ‘time of austerity’: A ‘time of austerity’

Setbacks like those seen at DPAC, though not uncommon in the charter sector, still come as a surprise to those who witnessed the network’s string of early victories.

In the fall of 2012, Democracy Prep Public Schools was already a known entity in its hometown of New York City and well on its way to gaining a national profile. The fast-growing charter school network, founded in 2006 by a 28-year-old former special education teacher named Seth Andrew, had already opened three middle schools throughout Harlem, along with a high school that was about to send its first graduating class to college. It had completed New York’s first takeover of a failing charter school and was launching another turnaround in Camden, New Jersey. By the end of September, it would receive a five-year, $9.1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education to expand to other states.

The 2012 grant application showcased Andrew’s deftness in attracting powerful advocates. Letters of support accompanied Democracy Prep’s request from Joel Klein, the New York City schools chancellor whose agency had proclaimed the original Democracy Prep campus the best middle school in Harlem; John White, the Louisiana state superintendent and a nationally known school reformer; and Roland Fryer, an influential Harvard researcher who had found that Democracy Prep students in New York made huge strides in both math and English.

The network applied for and was awarded an additional $12.7 million in 2016; its request was bolstered by more letters, including one from U.S. senator and now-presidential candidate Kirsten Gillibrand. In a blog post marking the conclusion of the grant, network CEO Katie Duffy, who replaced Andrew in 2013, was effusive about its success. “Five years ago, it was nearly impossible to imagine a Democracy Prep that not only spans the Northeast Corridor but which extends into the Bayou and out to the Desert,” she wrote. “Now, it is equally impossible to imagine a Democracy Prep that does not.”

Eighteen months later, Democracy Prep can no longer be said to span the Northeast Corridor. After four years of poor academic performance, the network announced in August that it would be pulling out of its location in Washington’s Anacostia neighborhood.

In late January, Duffy emailed the staff warning of “significant deficits across our network of schools and at Democracy Prep Public Schools.” The shortfalls had arisen from insufficient financial management, along with student attrition and under-enrollment; a period of belt-tightening was underway, she wrote.

The announcement followed the termination last fall of the network’s chief financial officer. Asked about the firing, Duffy indicated that the former CFO had missed warning signs around Democracy Prep’s incoming “time of austerity” or had neglected to pass them up the chain.

“He had a tremendously hard time communicating, especially around bad news,” she said. “And the lag between his communication and the reality just became untenable.”

The former executive, who asked the 74 not to use his name, said that he often wasn’t the first to hear bad news: “A lot of what impacted the financial information … got to me long after it made it to Katie and the directors,” he said.

A few weeks after that interview, Duffy began an extended medical leave. In her absence, Trivers — a former principal with the network who has been its superintendent for the past two years — will serve as interim CEO. A return date for Duffy has not been specified.

Democracy Prep officials offered no further details. Duffy could not be reached for comment.

Underpopulated classrooms: Underpopulated classrooms

The gradual move into new territories brought some of Democracy Prep’s challenges to the surface, but some have been present for years in the network’s home base in Harlem.

Like many “no excuses” charter schools (so named because they accept no excuses for students failing to reach their potential), Democracy Prep has historically struggled to keep all its admitted students enrolled. A 2012 study conducted by public radio station WNYC listed two of the network’s middle schools among New York City’s 10 worst for student attrition.

Network founder Andrew said that the reality of the network’s high attrition rates was nuanced. Some students, though happy at Democracy Prep, left for coveted slots at specialized schools elsewhere in the city. Others were from families who had moved out of commutable distance.

But a key driver for student departures is Democracy Prep’s higher-than-usual academic standards. Aside from special education students with IEPs and those backfilled in after ninth grade — admitted to fill seats that other students have vacated — all network high schoolers in New York must graduate with an Advanced Regents diploma, which requires higher scores on state standardized tests. Those who miss the cut face the unattractive prospect of being held back, which can drive them to other schools simply to be promoted and move closer to graduation.

Those rigorous academic expectations have yielded some terrific results: According to the charter management organization, some 80 percent of Democracy Prep graduates enroll in college, a rate much higher than the national average for low-income students like those that make up most of the network’s pupils. Yet critics also point to the various schools’ year-over-year enrollment figures, which show that large numbers of students leave during their freshman and sophomore years.

The network’s former CFO, noted that sustaining enrollment is a persistent challenge for charter schools, particularly those with rigorous academic expectations.

“If you have a student who wants to change schools, for whatever reason, they can do so quite easily. As well, you have to consider graduation requirements for the different charters. If a charter has rigorous requirements for graduation, it may make it difficult, if not impossible, to backfill students who have left in the upper grades.”

Underpopulated classrooms are a problem for a school that is seeking to rapidly increase its footprint, but they quickly give rise to a bigger issue: In education, head counts make bankrolls, and when students leave a school, their education funding walks out the door with them. This is a somewhat ironic lesson for charter schools to learn, given that they have been accused for years of poaching students and state funding from their neighboring district schools.

At Democracy Prep, the problem of student attrition is no mere abstraction. It is perhaps the most serious obstacle impeding the network’s continued expansion to new states and cities, and a threat to sustaining its existing presence.

The numbers tell the story: The initial ninth-grade class of Harlem’s Democracy Prep Charter High School numbered 79 students, according to its 2009-10 New York State School Report Card. But by the time the class graduated — in a grand celebration at the famed Apollo Theater during which UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon gave a commencement address — just 46 seniors collected diplomas.

The economic straits Democracy Prep finds itself in have necessitated some changes. From the beginning, one of the organization’s core principles has been to operate all campuses solely on public dollars provided by home states and cities. The purpose of that commitment was to preserve institutional independence and prove that charter schools can exist and thrive without the wealthy patrons who often shelter them.

Recently, the network has reconsidered that policy as it tries to re-establish its fiscal footing. The shift is a direct response to its inability to meet enrollment targets that Trivers called “aspirational.” For instance, she said that current enrollment at DPAC stands at 980 students, while the original target was 1,150. An overprojection of 170 students, multiplied by Las Vegas’s 2018 per-pupil expenditure of $8,959 (as reported by Clark County School District), would amount to a budgetary shortfall of just over $1.5 million.

“We did throw a lot of … energy and support and resources into drumming up enrollment and doing student recruitment efforts and all that,” she said. “It was a mistake to budget based on the target — just really hoping we could fill every seat in that beautiful campus — if we weren’t yet able to see any historical data that would tell us that our efforts would prove fruitful.”

There have been other challenges along the way, Trivers noted. Upkeep on the sprawling DPAC facilities has its costs, and transit arrangements in both Baton Rouge and San Antonio are much more complex than in Harlem, which is accessible by multiple subway lines. Per-pupil education funding in Texas, Louisiana and Nevada, where Democracy Prep has opened or turned around schools in the past four years, is less than half of the roughly $22,000 that New York State provides.

But the combined effect was inevitable: Both individual campuses and the network have had to institute cost-cutting measures. Hiring has been frozen for the remainder of this school year. Non-essential travel has been eliminated, and the network isn’t paying out for unused personal days. And staff have been let go.

“We ended up needing to adjust and do layoffs, which is never something that we want to do,” Trivers said. “And we tried every other sort of recourse that we could, but that’s what it came to.” Particularly in Las Vegas, she said, “We saw more attrition throughout the year where we lost a few students at the elementary school and quite a few students at the high school. So the [combination of] not meeting the original enrollment target and then further attrition throughout the year is what kind of led us to that point.”

‘Funbruary’ in the nation’s capital: ‘Funbruary’ in the nation’s capital

Trivers said she’s proud of what the network’s expansion has done to improve education options in host cities, speaking movingly about a graduation ceremony she’d attended at Camden’s Freedom Prep. The Democracy Prep civics program has evolved since its early days, she added; elementary schoolers still hit the streets to get out the vote on Election Day, but middle and high schoolers now also participate in a robust school government program that exerts real influence over how their campuses are run.

Academically, she added, this year’s interim assessments from both Baton Rouge and San Antonio showed substantial student test score growth in math and English. And the wide array of civics-oriented offerings — days of service and public advocacy, high school-level courses in civics and get-out-the-vote campaigns timed to coincide with local elections — have been implemented across the network.

Still, those successes have been overshadowed this year by Democracy Prep’s retreat from Washington. Perhaps nowhere has the expansion been more fraught — or more bitterly ironic — than in the nation’s capital, where one would have expected the network’s civics-minded philosophy to find a welcome home. Instead, the Anacostia campus will close June 30.

That school, Democracy Prep Congress Heights, was begun in 2014 as a turnaround of a severely underperforming charter, Imagine Southeast. Last August, after four consecutive years of diminishing academic returns, the network announced that it would end its efforts in the capital and attempt to recruit another charter operator to undertake a second turnaround.

That search proved futile; even in a area as charter-saturated as the District, no other organizations came forward to clean up the mess at Congress Heights. The school’s new administration and board severed its ties to the Democracy Prep network, which no longer lists Washington as one of its host cities. Though the school’s new leadership petitioned the D.C. Public Charter School Board — the body that authorizes most of the city’s schools of choice — to renew their charter, they were declined. In a letter to parents sent in January, the school formerly known as Democracy Prep announced that it would be closing permanently.

Four years earlier, though, the new school looked like a godsend to an underserved community with few high-quality options.

A program centered on democracy and civic involvement — located in the center of American national politics? To Ethiopia Berta, a kindergarten teacher who started at DP Congress Heights in 2015, it sounded incredible. She’d just wrapped up her second year as a Teach for America corps member in Baltimore, and the idea of stoking civic engagement in one of America’s poorest, most disenfranchised communities was particularly appealing.

“I thought it was amazing that that was a part of the school,” she said. “This was how they wanted the school to be run and the scholars to be taught. This is what you want scholars to take from education: not just to be a scholar, but a citizen scholar who is responsible and aware of their surroundings. That was definitely a big pull for me.”

But right away, she could tell that the school culture was troubled. The turnaround had been underway for a year before her arrival, and much of the staff was united in opposition to Congress Heights’s young executive director, Sean Reidy. A former Democracy Prep teacher in New York who had gone on to earn an MBA, Reidy was recruited to spearhead perhaps the toughest assignment any school leader can take on — being the public face of a school turnaround in a neighborhood historically ill-served by the education system. Berta said that even his fellow administrators seemed eager to undermine him, and she described the leadership culture as “toxic.”

Contacted by The 74, Reidy declined to comment on his tenure at Congress Heights.

Uniforms are often a bone of contention in no-excuses schools, which maintain strict standards for order and appearance. But at Congress Heights, students were often sent to a “reflection room” for not wearing all-black shoes. Berta said that the rigidity betrayed both an ignorance of the deep poverty in Southeast Washington and an arbitrary observance of the rules.

“It’s really ridiculous to send a kid to a reflection room to reflect about a thing they can’t change. You can’t change the fact that you have one pair of shoes,” she said.

In an email to The 74, Trivers noted that students have access to teachers and curricular materials in reflection rooms, and that time spent there “allows for scholars to have a moment of repose, to reflect on their actions.” The network’s uniform code, she added, “is clearly communicated to scholars and families at the start of and throughout each school year. We do enforce that uniform code.”

It’s always the watchword of school leaders to avoid alienating the families they aim to serve. But those facilitating turnarounds must also steward their goodwill with staff, who are worked hard and are often overstressed. Rick Cruz, chairman of the D.C. Public Charter School Board, said his site visits to Democracy Prep Congress Heights revealed an obvious disconnect.

“Certainly, if you’re taking on a takeover — stepping in and having to reinvent the school, and to do so with literally hundreds of students in the school — it requires strong leadership and excellent execution. And those things were missing. In particular, what I notice on my visits is the culture: Are teachers and staff feeling well taken care of, building strong relationships with students? That was not happening, and that’s what led, I imagine, to the results that we saw.”

Those results were poor, both academically and culturally. Students at Congress Heights scored far below the citywide average on math and English, and the school had a suspension rate five times as high as those in other Washington schools. Those who had come in lagging behind children in other neighborhoods ended up receding further into the distance.

The situation wasn’t helped by a punishing churn in top-level leadership. Including an interim period after Reidy was let go, three executive directors led Congress Heights in just four years.

“After Sean was fired, it was a domino effect of instability,” Berta said. “It really set the tone. Every year, we knew we were going to have a new leader.”

But the problem went deeper than that: As an operator, Berta said, Democracy Prep did not always appreciate the differences between New York, where its program had thrived, and Washington, where it was an unknown. In Anacostia, an area of the city that is almost uniformly black, a number of lessons made reference to characters shopping at bodegas. Children who had never heard of such businesses were confused.

Worst of all was the lack of observance of Black History Month, practically a hallowed time of year in Washington. When February academic schedules were circulated, they focused primarily on the celebration of “Funbruary,” a monthlong sequence of activities intended to lift student spirits in the midwinter and invoke the network’s dragon mascot. Berta said that she and her fellow teachers had to insist on more content dedicated to the famous figures and events of African-American culture.

“Carter G. Woodson [the seminal black historian] is a real person; he’s not a dragon,” she said. “We should acknowledge that and acknowledge the fact that we’re in Southeast Washington, which is a huge, huge black community that is enriched with so much history. So why are we not acknowledging that? Frederick Douglass’s house is literally down the street from our school, and we’re celebrating Funbruary.”

The promise of opening a Democracy Prep campus in the nation’s capital initially drew in Hannah Kim, who leaped at the chance to join the school’s board. Kim, at the time communications director for long-serving Harlem representative Charles Rangel, was fast becoming another of Democracy Prep’s army of boosters. A Korean American, she was drawn to the school’s efforts to integrate Korean language and culture into its pedagogy, and she was impressed by its lofty reputation within the academic world.

“When I like something, I really like something,” she said. “We helped secure the initial grants from the Education Department. … It’s what members of Congress are supposed to do. We help organizations in our districts to get grants. You can’t help it when there’s a very successful organization in your congressional district that’s turning the city around.”

Kim sat on the school’s board from its founding through December 2016. Though she still enthusiastically supports the network’s vision — she called Seth Andrew a “genius” who could one day serve as U.S. secretary of education — she argued that it hadn’t learned from the mistakes of the District’s hard-edged school reform regime under former chancellor Michelle Rhee. The politically conscious local population, she remembered, was still smarting from battles with Rhee and former mayor Adrian Fenty when Democracy Prep came on the scene.

“All politics is local,” she said. “The politics of this whole charter school, young elitist, Teach for America alums — outsiders coming in and saying, ‘We’re going to make it better’ — it didn’t sit well. I could see the remnants of the trauma, if you will. It was still in people’s minds: ‘Hey, are these guys trying to pull a Michelle Rhee here?’”

The perils of expansion: The perils of expansion

Trivers said that the lesson she takes from Democracy Prep’s failure in Washington is to adopt a more deliberative approach in opening new schools. She noted that the network was working to open regional offices to better serve its outlying campuses, but she added that it might be necessary to build in a year of observation, consensus building and leadership development before taking the leap.

“We need to take a lot of time and care with a Year Zero situation before going into a region. What I mean by that is [putting] into the expansion plan a year that is spent doing research, planting seeds with community partners, getting to know the whole landscape … and really treating that as a 12-month ramp-up to the year we’re going to start.”

Democracy Prep’s former chief financial officer noted that the $21.8 million in grants the network received from the U.S. Department of Education’s Charter School Program was earmarked explicitly for opening new campuses. Slowing the pace of growth could complicate their efforts to meet the terms of the grant, he said.

“You have to remember that expansion mandate by the CSP. I’m not sure if they have any choice [but to continue opening schools]. I don’t think they can throw on the brakes and say, ‘OK, let’s take a breather for the next three years.'”

In its 2016 application for new expansion funds, the organization set a goal of opening an average of four new schools annually over five years, with an aim of enrolling more than 11,000 students by the end of the 2020-21 school year. In notes on the application published by the department, however, reviewers said that mark “seems too ambitious for an applicant this size.” Indeed, though roughly 6,500 students attend Democracy Prep schools, it had proposed enrolling 2,000 more by this time.

Democracy Prep had continued scouting new sites to expand until quite recently, expressing an interest in either opening new charters or taking over existing ones in Florida and Kansas City last year. In March, the network notified Arkansas education officials that it hoped to gain a toehold in Little Rock in time for the 2020-21 school year.

But Trivers said the network was “hitting a bit of a pause button” on opening new locations during the 2019-20 school year, and that their talks with authorities in new regions were not tantamount to final decisions to expand there.

“It’s always been a part of our DNA that we’re going to grow and we’re going to take on risks, and we still plan to do that in the fall of ’20. It’s just that we’re taking a moment to step back and make sure that we can learn from mistakes,” she said.

As the network ponders changes to its strategy over the next few years, Ethiopia Berta reported that she and her fellow teachers are doing so as well.

As one of the few educators who have stayed at Congress Heights the past four years, Berta has seen many colleagues leave the profession entirely, burned out from the failed turnaround. She’s considering doing the same. In a bit of irony, the experience may have activated her own sense of democratic initiative.

“It made me think, ‘Are you going to continue to be part of a system that just tells people what to do — and they do it — or are you going to be a change agent and actually make a difference in this space?’ So I’m no longer choosing to be in the classroom. I’m really considering how policies in education are created, informed and decided upon.”

This article was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Lead photo: Democracy Prep elementary students visit the Washington Monument in 2013. (Democracy Prep)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter