A Manhattan High School Reframes How Slavery Is Taught Using The New York Times’s 1619 Project

Updated, Nov. 6

Jeremias Mata started his junior year thinking he’d already learned everything he needed to know about slavery.

“When I found out I was going to learn about slavery [this year], I was like, ‘Urgh … again?’” said Mata, 16, sitting in his 11th-grade history class at the Facing History School in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen. Over time, he’d connected slavery with hopelessness and a certain simplicity — that many black people had once been slaves, and that was that.

“But when we got into it” this year, he continued, “it was a lot of stuff that I didn’t know about.”

Part of what’s making this year’s lessons novel for students like Mata is an addition to the school’s history curriculum: The New York Times’s 1619 Project — a compilation of essays and poetry, penned almost entirely by black authors, that re-examines slavery’s legacy in the U.S. 400 years after the first enslaved people arrived here from West Africa.

The project, released in August, is helping schools nationwide reframe how slavery is taught in a way that captures its brutality, complexity and influence in shaping America, while also affirming the experience as integral to black Americans’ identity and their contributions to the country. Already a supplemental resource this year in every Chicago public high school, the project isn’t mandated material in the country’s largest school district. Its launch this summer, however, coincides with a new city education department policy encouraging schools to adopt curriculum that’s relevant to marginalized students’ experiences.

For many communities, having what’s known as culturally responsive education and implicit bias training is “a matter of life and death,” Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, a vocal advocate for the policy, said at a panel discussion last month. New York City is a predominantly minority district — about 26 percent of students are black, 41 percent Hispanic, 16 percent Asian and 15 percent white — and many schools are deeply segregated.

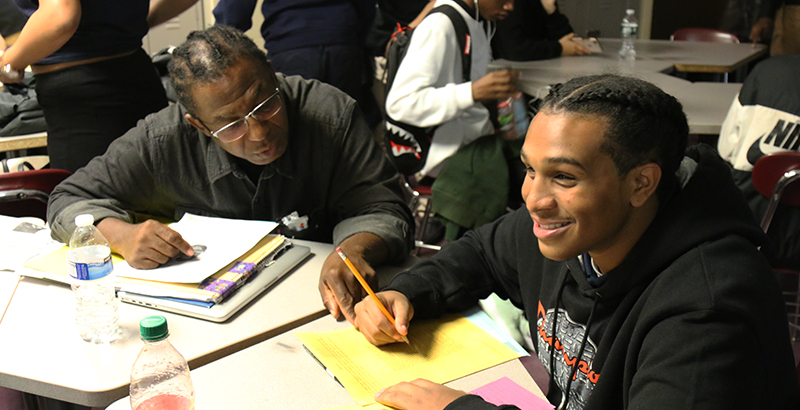

“It’s extremely important, especially with the student body that we teach here,” said Eric Albino, a history teacher at the Facing History School, whose enrollment is roughly 25 percent black, 71 percent Hispanic or Latino and 2 percent white.

The decision to intermittently weave the 1619 Project into the class curriculum throughout this year was immediate, co-teachers Albino and Alexa Achille said — especially as it aligns with the school’s existing mission to “recenter” history around “people who are often forgotten.” The district school, which opened in 2005, is one of the nonproft Facing History and Ourselves’s 19 partner or lab schools in the tristate area.

It serves 359 students in grades 9 through 12, many of whom commute from Washington Heights, Harlem and the South Bronx. It’s one of the city’s more than 30 “consortium” schools, small schools that teach a few subjects deeply to students who demonstrate their learning through a portfolio of oral and written work. Students are exempt from all but the English Regents exam.

While race plays a critical role in teaching the 1619 curriculum — and other parts of history that are often glossed over — Albino stressed that its lessons are important to all students.

“The general scholarship of topics like this needs to be pushed,” he said.

Mata and his peers spent class on a Thursday morning in late October digging into parts of the 1619 Project. One poem depicted the devastating emotional and physical toll that the transatlantic journey known as the Middle Passage inflicted on those bound for slavery in America. Others told the story of how enslaved people, including Native Americans, erected much of the country’s early infrastructure, from railroads to churches, and how slave labor fed a surging cotton market that enabled America’s rise as a global economic powerhouse.

“I kind of feel like it gives me a new sense of what it means to be gritty. To make it out of a bad situation,” said Mata, whose family is from the Dominican Republic and Cuba.

Mata said he doesn’t believe that his peers attending other district schools are getting the same exposure to these in-depth conversations about slavery as he is now. He thinks they should.

“It relates to a lot of stuff that happens now,” said Mata, alluding to the prevailing racial inequities and tensions roiling the country. “People of color are automatically one step behind other people. Because of slavery, that was a barrier that was put in front of them, and it took them a long time to break out of it. Even now.”

Cotton, slavery and the building of America

Albino and Achille saw an opportunity to surface the 1619 Project last month during a history unit exploring the roots of early America from the 1600s to the 1700s — a time frame that coincides with the start of American slavery.

Class that Thursday morning began with students comparing two poems by author Clint Smith: one on the Middle Passage, and a second describing the despair and hellish conditions inside the New Orleans Superdome, where thousands of residents were held for days without adequate water, working toilets or power as Hurricane Katrina ravaged the Louisiana city.

“I slide my ring finger from Senegal to South Carolina and feel the ocean separate a million families. The soft hum of history spins on its tilted axis. A cavalcade of ghost ships wash their hands of all they carried.”

“Before desperation descended under the rounded roof … There were families inside though there were some who failed to call them families … There were people inside though there were some who only saw a parade of disembodied shadows.”

“What are the similarities?” asked Albino, who that day taught the class without his co-teacher, Achille.

Class participation, at first, was subdued. The 15 or so students were infants when the historic hurricane made landfall in 2005, and they didn’t appear to have much context.

Albino expounded a bit more. He displayed an image of the city submerged underwater on the class prompter, noting, “Everything you see on there is a roof.” He explained how the government inadequately prepared for and responded to the hurricane — a decision that left many poor black people stranded to bear the brunt of the storm.

He asked again: “How does Hurricane Katrina and the way it played out in New Orleans reflect the legacy of slavery?”

Answers started trickling in. One student likened the packed Superdome with the confined space on slave ships. A few identified how both groups of people lost control. “Originally with slavery … all of a sudden they were taken abruptly to a whole new land,” one of the students said. With Hurricane Katrina, “These people were living their normal lives and then this hurricane came, basically forcing them to restart.”

“The hurricane is a metaphor [for] the white people, taking all of the black people from their homes and taking them away from [comfort],” another surmised.

Albino piggybacked off of the last student’s interpretation. “It’s kind of a reflection of the dehumanization that plays a role throughout American history,” he said. “These poems, I thought, really nailed down this connection.”

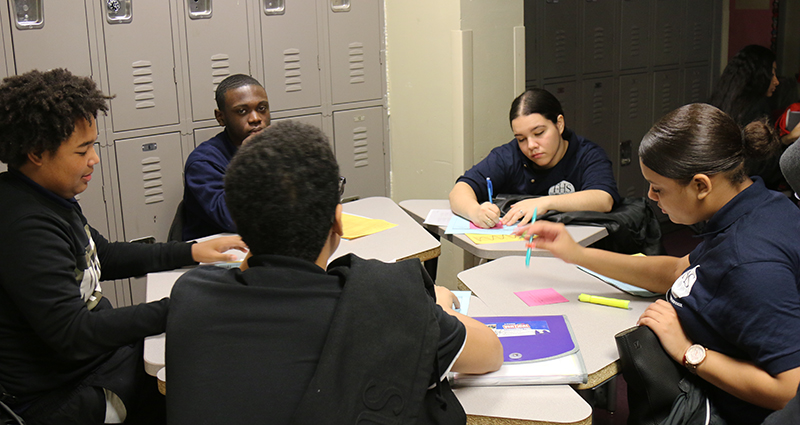

The class then split into groups to analyze four other short poems and essays, which underlined slavery’s role in U.S. wealth and trade, the connection between police brutality and power dynamics and the roots of black mistrust in the medical system. Students were preparing to submit their first major assignment for the unit — an essay on how identity affected power in early America — and their teachers wanted them to cull compelling quotes from the 1619 materials about slavery’s impact to add to their final products.

Discussion was particularly lively at one table around the essays “Fabric of Modernity: How Southern Cotton Became the Cornerstone of a New Global Commodities Trade” and “Municipal Bonds: How Slavery Built Wall Street.”

“New Amsterdam’s and New York’s enslaved put in place much of the local infrastructure, including Broad Way and the Bowery roads,” one student read from the latter essay about the creation of the two iconic city streets. Another lifted a quote on how the cotton trade initiated modern-day contracts: “From the first decades of the 1800s … the sheer size of the market and the escalating number of disputes between counterparties was such that courts and lawyers began to articulate and codify the common-law standards regarding contracts.”

These readings prompted 15-year-old Justin Ventura to make a self-proclaimed “pretty controversial” statement to his classmates.

“I don’t feel like slavery was good, but it was kind of necessary for the world to become what it is,” he said. “Obviously we had to start somewhere, build from the ground up.”

Those at his table were in agreement. One female classmate, venturing away from the readings in front of them, added that slavery and the civil rights activism that ensued a century later to try to undo its harmful legacy ushered in equal rights laws, including in education.

Darielle Santana, 16, said he finds it all “very interesting.”

“In my other schools, I would just learn that slaves came, they worked on the plantations, were mistreated and then were freed after the Civil War,” Santana said after class. “But now I actually learn … how this history impacts us today.”

Like Mata, he wants his friends to learn too. “They should know about 1619,” he said.

Changing how history is taught districtwide

Teaching curriculum that focuses on the perspectives of often-overlooked groups is not mandated in New York City. But district policy does recommend the practice, and schools and educators can choose to bake it into their class lessons, as teachers Albino and Achille have done with the 1619 Project.

If teachers want “to take the opportunity to provide more perspective on the subjects that they’re talking about so students get a deeper understanding, they can use pieces of what we’re doing if they have time to pause and reflect,” Achille said.

The city education department has identified specific existing resources for educators “that can be enriched by essays and poems from 1619,” a spokeswoman wrote in an email Tuesday. New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones’s lead 1619 essay, for example, can tie into eighth-grade-level Passport to Social Studies lessons on Brown v. Board of Education and the Little Rock Nine and a Hidden Voices Project profile on David Ruggles, an African-American abolitionist in New York City in the 1800s. The DOE will host professional development sessions that “examine certain aspects of the 1619 Project” this school year, she said. The district announced in a report last week that it invested $23 million in culturally responsive education and implicit bias training in 2018-19.

Facing History and Ourselves hasn’t developed its own curriculum around the 1619 Project, though it pointed to its lesson on reparations that ties in those materials. Much of the nonprofit’s work in the city involves its collaborations with the education department to provide history curricula such as Civics for All lessons to more than 700 schools, said Pam Haas, the organization’s executive director for New York. The organization also conducts professional development trainings relating to bias, hatred and equity, she said.

Yet another avenue is the Pulitzer Center, a nonprofit journalism organization that offers a 1619-specific curriculum — and a space for teachers to share creative lesson plans — along with a free online version of the project. While the Facing History School teachers didn’t explicitly follow the center’s curriculum, it’s an “inspiration,” Albino said.

Despite widespread interest in the project, this approach to teaching history hasn’t been without criticism. Some worry that Chancellor Carranza’s intense focus on race, class and equity is a distraction from the urgent need to teach basic math, reading and science. The 1619 Project specifically has also struck a nerve with more conservative critics, who don’t consider slavery part of “the essence of America” and who believe that the U.S. definitively moved past this “original sin” after the Civil War and subsequent civil rights movement.

For educators who want to dive in, Facing History School’s Assistant Principal Calee Prindle urged professional development training on how to broach difficult topics in the 1619 Project with their students. Facing History and Ourselves cited various webinars teachers could listen to, like this one on creating “class contracts” where students agree on expectations for how members of the class will treat one another during tense discussions.

“It could be really harmful if you just say, ‘Go do this curriculum,’ and teachers aren’t trained to create positive relationships with students, to have brave spaces in classrooms,” she said.

Teaching history with the 1619 Project is an ongoing process, Prindle added. She’s eager to see what’s next.

“I’m really excited to see … how it will manifest itself, especially in the spring semester,” she said. “The journey has just begun, really.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)