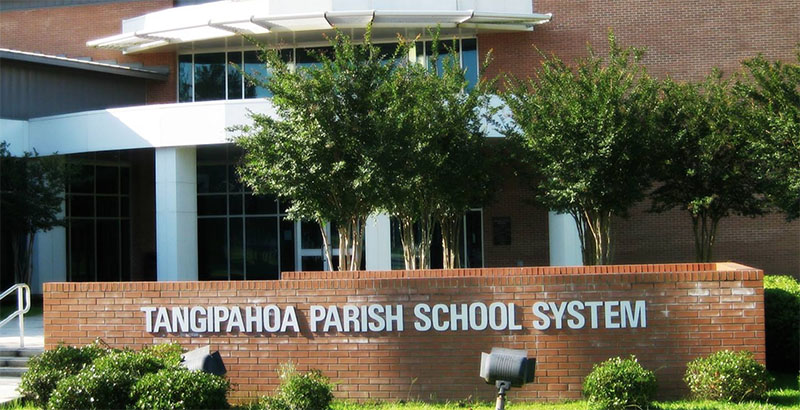

One of the Nation’s Oldest Desegregation Cases Might Settle This Week in New Orleans. After 54 Years in the Federal Courts, What Has It Accomplished?

Update November 21:

At a hearing Wednesday at the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, there was no resolution to the long-running Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board case. After six hours of testimony, Judge Ivan Lemelle suspended the hearing, which is set to resume on January 3.

In an interview with The 74, Tangipahoa Parish School Board President Sandra Bailey-Simmons said that the reprieve will “give the community a chance to meet and talk over this final agreement that we put together as a board.” While some had hoped Lemelle would approve a proposed agreement between the Moore plaintiffs and the board, Bailey-Simmons said she saw the hearing as a healthy development. “It’s a positive step,” she said. “There’s no doubt about it, we’ve come a long way.”

“Once again we embark on the well-traveled roads of Tangipahoa Parish.”

So begins a ruling from the United States Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in May 1979. The court, based in New Orleans, was attempting to disentangle a legal complaint that had inched along for years: A group of eight black teachers from southeast Louisiana had been dismissed or demoted when the local school district was compelled to integrate, and had turned to a lower court to be reinstated and awarded back pay. The defendant, the Tangipahoa Parish School Board, appealed.

It was a common enough story. In the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education and the myriad legal fights that followed, hundreds of districts throughout the South and elsewhere found themselves forced to merge separate-and-unequal school systems. White teachers generally weren’t the ones made to look for new jobs: According to one recent study, the long transition reduced black teacher employment in the South by nearly one-third.

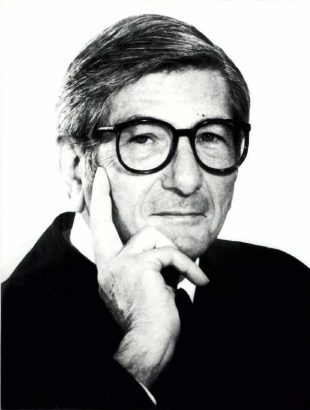

After batting about both sides’ “tortuous” legal arguments, detailing a series of motions and appeals that had carried on throughout the 1970s, Chief Judge John Robert Brown ruled in favor of the teachers, openly wishing that “this nearly ten-year-old case has hopefully come to an end.”

Judge Brown couldn’t have possibly guessed how many more footfalls would pass over the winding trail he had just spent several thousand words exploring. Though the immediate legal question of the terminated teachers’ rights was dispensed with, the case of Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board, initially filed in 1965, was nowhere close to being settled. The case continues still, five decades on, following the deaths of most of the judges and lawyers who originally adjudicated it. Even the plaintiffs, schoolchildren when the case was filed, have long since passed into middle age and beyond.

But all that could soon change. Fifty-four years into the Moore saga, a hearing Wednesday in New Orleans could finally put to rest one of America’s longest-running integration lawsuits. The case — reactivated a little over a decade ago after years lying dormant — could at last conclude, pending approval of an agreement forged between both sides over the past year. If that approval comes, Tangipahoa Parish schools would at last be granted “unitary” status, the final declaration that a system has eliminated the effects of segregation.

Brett Duncan, who won a seat on the school board in 2010 with the hope of helping the district end the suit, said a resolution is in sight.

“We’ll still have a final agreement where we have promised and made commitments to the plaintiffs on our intentions, and we invite the plaintiffs to hold us to that agreement,” he said. “We’re right there, and we’re anticipating that the judge will approve it.”

Local onlookers, some of whom remember the painful early days of integration a half-century ago, seem eager to move past a racial saga that began while Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon Johnson were still alive, before the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Black residents stand to gain some assurance that their children have a fair chance in local schools, and the district will receive greater autonomy over its finances and operations, allowing leaders to focus more closely on improving schools for all students.

But the close of one draining and complex legal battle, while long sought, will not bring an end to the significant educational challenges facing Tangipahoa’s schools, which are largely underfunded and underperforming. And whatever ruling comes down, it won’t erase a vexed era of local history any more than Judge Brown’s decision did 40 years ago.

Samuel Hyde, a professor of history at Southeastern Louisiana University, offered a measured assessment of the case’s legacy.

“For black people, I believe their quality of life has been improved by being a part of one school system rather than a separate system,” he said. “For white society, their ability to understand the needs and concerns of the other side has been dramatically improved. What I don’t think has improved is the quality of the schools.”

A campaign of harassment

Hyde has had ample opportunity to observe the progress of integration in the parish. As the director of the Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, he is a specialist in the history of Tangipahoa and the seven other “Florida Parishes” — so named because they once made up part of the short-lived British colony of West Florida, east of the Mississippi River.

The parishes exist somewhat outside the Creole-and-gumbo ecosystem that predominates in popular depictions of Louisiana life. Towered over by huge forests of long-leaf pines, communities of Scots-Irish, Italians and freed blacks gradually popped up to service a booming trade in logging and paper.

The area’s growth was marked by eruptions of violence, often directed at the descendants of slaves. On Friday, nearby Washington Parish will mark the centennial of the Bogalusa Massacre, when an armed mob attacked a group of labor organizers attempting to organize a cross-racial union at the Great Southern Lumber Company, then the largest sawmill in the world. Four white unionists were killed defending one of their black comrades, and the organizing drive was crushed.

A native of the area, Hyde chronicled the brutality in his 1998 book Pistols and Politics, a study of the extraordinary rates of rural homicide endemic to the Florida Parishes in the 19th and 20th centuries. Vigilante murders and Hatfield-McCoy-style feuding raged to the extent that Tangipahoa Parish was commonly referred to as “Bloody Tangipahoa,” he found.

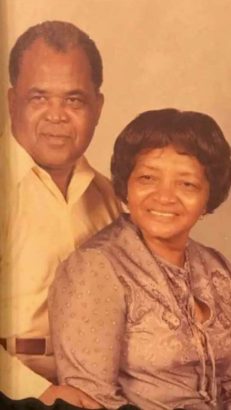

This was the historical backdrop against which M.C. Moore, a truck driver and father of 15 in the small city of Hammond, sued the parish school board in federal court in May 1965. He filed the suit on behalf of his children, who he believed were receiving a subpar education in local schools that remained overwhelmingly segregated more than 10 years after Brown v. Board.

It was one of hundreds of legal actions unfolding across the South at the time, and at first it proceeded quickly: Within months, Tangipahoa was ordered to implement a desegregation plan based largely on nondiscrimination and family choice. Several years later, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such plans didn’t do enough to end de facto segregation — in Tangipahoa, it was found, the proportion of black children attending integrated schools actually declined from 4.1 percent to 3.6 percent under the district’s freedom-of-choice system — District Court Judge Alvin Rubin required the school board to take more active measures. Those measures included school consolidation, one of the hallmarks of integration’s more assertive second phase.

It was the beginning of something. After centuries of second-class citizenship, enforced through legal writ and mob violence, Tangipahoa’s black students would learn and play alongside white classmates.

But progress came with a price. Months after filing the lawsuit, Moore awoke in the night to the sound of a gun being fired into his home; discovering that the phone lines had been cut, he sent his wife running to call for help from a neighbor’s house. The bullets had only narrowly missed the bed where the Moores’ young son was sleeping.

A group of friends arrived to defend the family, but they couldn’t prevent the campaign of harassment that followed. Moore was sent on far-flung jobs hauling pulpwood through swamps, where his truck would get bogged down. Someone made a habit of pouring sugar into his gas tank, and soon he abandoned the work altogether to bake and sell pies with his wife. One Moore daughter, newly assigned to a majority-white school, cut classes because of the stress.

Years later, Hyde interviewed M.C. Moore and his wife at their home, which still bears bullet marks from a darker era. Their lonely fight had left scars.

“What struck me was how intimidated they still seemed about it,” he said. “They were cautious with me at first, and they weren’t really sure what I was there about.”

Hyde’s experience with the case is personal as well as professional. The white son of a local school principal, he became a target when desegregation commenced in his fifth-grade year. Physical bullying was only one manifestation. One night, a white father called the house in a rage, claiming that a black teacher had taken a toy from his son.

“I answered the phone, and the man told me that — I’ll quote him: He said he was coming to get Daddy, and said he would cut his throat if he didn’t make ‘that nigger’ give it back,” he remembered. “Everybody was angry at Daddy.”

A harrowing transition

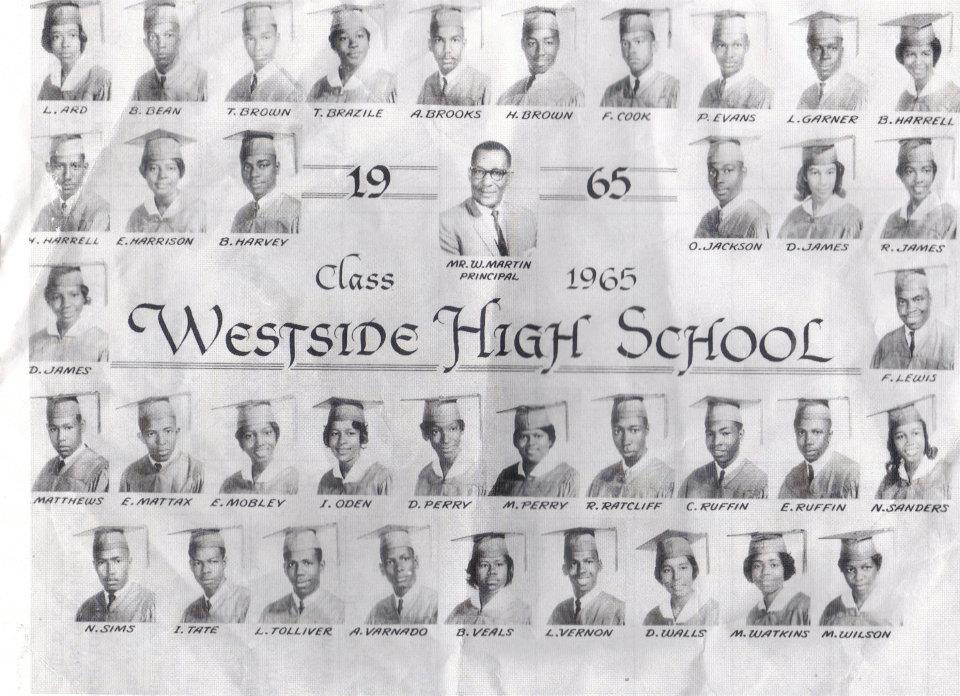

Of course, the transition was much harder for black students, many of whose schools were closed or merged with predominantly white schools. Antoinette Harrell is a local author and genealogist who has closely studied the history of the Moore case. Her family moved from the area in 1972, but she remembers with excruciating clarity the mistreatment she suffered as a fourth-grader, when she was transferred from the predominantly black Westside Elementary to the mostly white Amite Elementary.

Like many black students, Antoinette was held back a year — a demoralizing phenomenon she attributes to white teachers’ dim opinion of their intellectual abilities. One white teacher had fashioned a thick strap from an old fan belt, wielding it harshly against black students.

“I will never forget the look they gave us,” she said. “Like you belonged in somebody’s zoo.”

The experience stung all the more, she said, because of how much she had previously enjoyed school. The black teachers at Westside were figures she knew from her neighborhood and church — many the sons and daughters of sharecroppers who were conscious of their status as professional role models. They held students to high standards because they were more familiar than most with the absolute necessity of good schooling.

“We came from a school in the black community where the teachers really cared about our education,” she said. “And we were really bright students being told that we couldn’t read, couldn’t write. We felt like, ‘OK, we want equality of education, but if this is what integration is all about, I’d rather go back to the segregated schools.’

Many of those beloved black teachers lost their jobs as schools combined. Gideon Carter III, the son of one of the parish’s few black principals, was a few years older than Hyde and Harrell when integration began. A civil rights lawyer, he now represents the plaintiffs in Moore.

“It was not handled well,” he remembered. “My dad was a school principal, and my mom was a schoolteacher. A lot of their co-workers were terminated or demoted when the school system was integrated. A lot of black employees lost their jobs.”

“I will never forget the look they gave us. Like you belonged in somebody’s zoo.”

—Antoinette Harrell

Some joined the Moore case as plaintiffs, eventually forcing the district to adopt affirmative action policies in hiring teachers, coaches and other staff. More formal guardrails were put in place as the case evolved, with a court compliance officer detailed to the district office and Judge Rubin mandating that school board officials submit major financial and construction decisions to the court for prior approval.

But in 1977, Rubin was appointed to the Fifth Circuit, and the suit lost its most committed principal. For the next three decades, the desegregation plan seemed to be forgotten.

Lost momentum

The remarkable thing about Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board isn’t the heavy personal cost it exacted, mostly from black students and educators, or the fact that it didn’t fully realize its aims. Between white flight and limited administrative bandwidth, desegregation in schools has always been messy, at best, in its implementation. Few districts ever reached the level of racial heterogeneity envisioned by the activists and politicians who led the charge in the 1960s and ’70s.

What is striking, at least to an outside observer, is the sheer length of time during which little or no formal oversight was exercised over the school board’s progress toward integration. In the 1980s and ’90s, the case essentially remained at a stalemate: Tangipahoa schools were never declared unitary, but few attempts were made to enforce the court’s requirements on student assignment, hiring and facilities.

Duncan, who sits on the board and has led efforts to resolve Moore in recent years, suggested that both sides had likely thought it wise to allow the case to go dormant. For the plaintiffs, declining to close the matter allowed them to revisit it if the district began to backslide; for the board, it was a chance to put bad headlines behind them and “quietly let this thing go.”

“The courts started backing away, started losing interest.”

—Carl Bankston, Tulane University

“Rather than have the big fight to get final closure, they would just kind of walk away,” he explained. “The board went through the whole process of building schools, consolidating schools, they did all the stuff they were ordered to do. People were satisfied, but they just didn’t file the motion for unitary status. We have the benefit now of knowing that that was not a good strategy.”

Carl Bankston, a sociologist at Tulane University who has studied race and education in Louisiana and the broader South, told The 74 that across the country, momentum behind desegregation efforts began to dissipate during that time, only beginning to re-emerge at the beginning of the 21st century.

“Many people argue that there was a failure of will during those years, and legislatures simply let the issue of desegregation drop,” he said. “The courts started backing away, started losing interest.”

In Tangipahoa, interest returned in 2007, when the Moore family petitioned the court to reopen the suit. The move came in response to a hiring controversy, when the district declined to hire a qualified black applicant to serve as head football coach at Amite High School. While the rejection was somewhat predictable — in the previous 30 years, no black head coach had ever been hired at any of the district’s high schools — it disregarded the court’s long-standing requirement to fill new vacancies with black candidates until the district had reached a 40:60 staffing ratio.

Those requirements, along with many others that the court had imposed decades before, had simply been allowed to lapse. When presented with the complaint, District Court Judge Ivan Lemelle ordered the school board not only to hire the black coach but also to devise an entirely new segregation plan going forward. More than 40 years after M.C. Moore first filed the suit, Tangipahoa Parish was back at the drawing board.

Carter, the plaintiff’s attorney who has worked on the Moore case since that time, said that much of the past decade has been spent reviving legal bargains struck by the district while he was still a student there.

“These cases can go dormant, and nothing may be done for many, many years,” he said. “In this particular case, historically, there’s been an attitude of noncompliance with existing court orders. So over the past 10-plus years, we’ve entered agreements to bring the system back into compliance with the orders of the court.”

Edging towards settlement

That hasn’t been easy.

It is already a significant victory that both sides have agreed in recent months to an extensive settlement that will commit the district to achieving greater student integration through the continued use of magnet schools and intra-district transfers. New policies have also been proposed to actively recruit, mentor and retain a more diverse teacher workforce, among a slew of other goals. If the plan is approved by Judge Lemelle Wednesday, the effects will be momentous.

But the deal, which the judge may still reject, came after another decade of debate and legal maneuvering. A plan put forward by the school board in 2010, which would have spent millions of dollars to build three new schools, was crippled when local voters overwhelmingly rejected a tax increase to raise the needed revenue. The district has operated for years within an operational straitjacket, needing to attain the court’s permission before reaching decisions around hiring and construction. At the same time, far too few kids have received an adequate education in the district; the release of state test results this spring showed that just one-quarter of Tangipahoa students scored at mastery level, far lower than the rates at nearby St. Tammany, St. Helena, and Livingston Parishes.

Movement has come in spurts. The 2018 appointment of Superintendent Melissa Stilley — a former teacher who returned to lead the district after working at the Louisiana Department of Education — has been met warmly by the plaintiff side. Carter says that her fresh perspective has been “instrumental” in helping nudge the fight toward its conclusion. (Stilley did not respond to requests for comment for this article.)

And some concrete improvement has already been measured. A 2017 working paper by Northwestern University scholars Diane Schanzenbach and Cynthia DuBois found that the district has advanced somewhat toward the goal of a 40:60 ratio of black to white staff members. The resumed affirmative action policies were credited with bringing about the greater diversity.

Legal fees have totaled nearly $5 million since the case reopened, hardly an insignificant sum. According to Duncan, Tangipahoa is the least funded school system, per pupil, in Louisiana — which already funds its public schools at levels lower than the national average.

And data analyzed by Tulane’s Bankston suggests that, as the renewed battle over integration has gone on, white families have been fleeing Tangipahoa schools. White students made up 51 percent of the district’s enrollment in the 2006-07 school year, when the case was reopened; they account for just 43 percent today, a sizable drop in both absolute and relative terms. The percentage of white students in the parish attending private schools grew from 18 percent to 25 percent over the same period.

“There may be other things beyond segregation that affect this movement,” Bankston said. “But I think it is a pretty reasonable inference that the desegregation case makes some impact on these figures.”

The academic performance of the district isn’t helping matters. When the Louisiana Department of Education released its latest school performance scores earlier this month, three of Tangipahoa Parish’s schools received F grades, and another nine received Ds. Just one, the Southeastern Louisiana University Lab School, received an A. District officials touted some schools’ progress in closing achievement gaps, but clearly much work is left to be done.

Southeastern Louisiana University’s Hyde, who commends the work being done to improve and integrate classrooms, says that he is nevertheless grateful to send his young children to an Episcopal school in Baton Rouge, which he hopes will be a refuge from the kind of bullying he experienced as a student in the ’70s.

“There’s kind of a malaise about the schools now,” he said. “White support for them has waned by the year, and I think there’s a kind of despair among people now that anything’s going to change if the schools continue to be perceived this way. The wealthy people that could easily pay these proposed taxes abandoned the public school system a long time ago.”

Although a renewed focus on integration has recently migrated from niche policy circles to Democratic primary debates, America’s generational push toward greater diversity and equality in schools stalled some time ago. There is evidence showing that integrated classrooms yield real academic gains for minority students, but some research also suggests that concentrations of poverty, rather than racial isolation, are the true drivers of achievement gaps. In any regard, precious little progress has been measured in bringing the performance of the most disadvantaged students up to that of their more affluent peers.

Bankston, who acknowledges that lawsuits like Moore have been necessary tools to combat persistently segregated school districts, lamented that they often fall short of communities’ hopes. The human toll of segregated schools is intractable, and whether or not a district is ever declared unitary is a different question than whether the people who attended its schools are ever made whole.

“The whole idea of desegregation in schools, at least from the 1960s, has not been simply to open up schools to all comers, but also undoing the damage that past discrimination has created in schools,” he said. “Unfortunately, that damage is so deep-seated that it’s really hard to reach a point at which you can actually say that we’ve made up for all the harm that previous school boards have done. Instead, it ultimately ends when people say, ‘OK, we haven’t resolved everything, but we’ve exhausted all of our options, so we’re just going to call an end to it.’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)