Can Civics Education Allow Schools to Rediscover Their Democratic Purpose — and Help Rescue America From Decline?

By Kevin Mahnken | April 17, 2019

In an era of ‘fake news’ and loss of trust in political institutions, states, schools and philanthropies are increasingly turning to civics education as a way to stem the tide of cynicism and disengagement.

The results were historic.

The 2018 midterm elections were a generational moment of mass democratic mobilization. Americans opened their wallets, knocked on doors and swamped the polls in record numbers, hitting a 104-year high for voter participation to hand Congress to the Democrats and deal Donald Trump the greatest defeat of his presidency.

A thumbnail portrait of that political wave could be seen in New York, where speed-walking commuters were greeted on Election Day by a sight that has become familiar to them over the years. On the sidewalks of Harlem, swarms of students from Democracy Prep Public Schools, a local charter school network, clutch fliers entreating them to exercise the franchise. The youngest, some just kindergartners, wear yellow T-shirts printed with the slogan, “I Can’t Vote … But You Can!”

If passersby can’t be bothered to read them, the kids have been known to shout to get the point across.

THEY can’t vote but YOU can! If you live in New York, don’t forget your civic duty! Make sure you go out and vote today! #NYCVotes#NYPrimary #TBT pic.twitter.com/C3XA64KoGm

— DEMOCRACY PREP (@DemocracyPrep) September 13, 2018

Many of the kids had taken part in this ritual before. Democracy Prep, which comprises 21 schools in five states, lives up to its name by placing democratic action at the heart of its identity. The network’s 6,500 students regularly participate in Get Out the Vote drives not only in November but also in primary elections.

This past election cycle, the kids fanned out not just across Harlem, where the network was founded, but also in Las Vegas and Washington, D.C., where they canvassed on college campuses. Elementary school students lined the sidewalks of Camden, New Jersey, with handmade signs in English and Spanish. And a number of high school seniors headed to the polls themselves to cast their first votes.

WATCH — Inside Democracy Prep, a School Network With Civics in Its DNA, Students Are Embracing Their Assignments to ‘Change the World’

The schools’ street-level organizing is paired with a set of civics-related requirements intended to foster the skills of social participation. High schoolers must complete 40 hours of community service and also lobby public officials, compose a brief about a politician or policy proposal, provide an oral presentation (whether a public speech or testimony before a panel), submit an op-ed for publication and raise money for a cause. And every Democracy Prep senior must pass the U.S. citizenship exam.

This approach appears to be bearing fruit. Last spring, the policy research organization Mathematica released an extraordinary study finding that Democracy Prep students were 12 percentage points more likely to vote and 16 points more likely to be registered to vote than their peers.

Those results offer something of a first: proof that exposure to a particular educational model can dramatically increase rates of political action. Though it’s unclear how replicable the effects are, they have fed the hopes of both education experts and political scientists that schools hold the key to revitalizing a democracy that has spent decades toggling between apathy and bitter partisanship.

Americans are much more ideologically polarized — and less likely to read a newspaper, volunteer for a cause or trust the government’s intentions — than in past generations. Public opinion polling suggests that our long era of political antagonism has bred a growing disillusionment with democracy, especially among young people.

To David Campbell, a political scientist at Notre Dame who has written about civic education, those indicators are a chilling sign of the times.

“That’s something that, frankly, we’ve all just taken for granted: ‘Of course, [the U.S. is] a democracy, it’s always going to be a democracy,’” he said. “Well, we’re beginning to kind of rethink that. We’re nowhere near Venezuela, I’m not suggesting that, but there are cracks. And it’s not just because Trump got elected, because actually a lot of this stuff was coming up before Trump arose on the scene. We’ve seen evidence of this now for the last few years, and if anything, 2016 kind of galvanized our attention. Yeah, this is a moment.”

Emilyn Whitesell, a researcher who co-authored the Mathematica study, said the effects of attending Democracy Prep were “some of the larger impacts we’ve seen from a rigorously designed study.”

Meanwhile, a growing number of policymakers across the country — even those without an inkling of Democracy Prep’s existence — are willing to bet on civics education as an engine for building better citizens.

Two days after Election Day, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker signed a bill overhauling the state’s approach to civics education. The new law requires public schools to offer students the opportunity to participate in civics and community service projects beginning in eighth grade. Some of the bill’s proponents hinted that the effort was a direct response to America’s troubled political climate — perhaps one as clear as the election results earlier in the week.

The legislature’s education committee chair called the law critical “in light of … the perilous state of our country’s civic and political life today.” Months before, the speaker of the state House of Representatives had made the point clearer still, remarking, “The last year — in terms of what’s going on in the country, in particular — has convinced me about the need for further civic education and, through that, hopefully more civic involvement nationwide.”

Both were echoing sentiments percolating in the education world for several years. During and after Trump’s election, worried onlookers pondered whether a “Sputnik moment” (or, as others preferred, a “sphincter-check moment”) had arrived for civics education. Others have warned that inattention and apathy are watering down children’s appreciation for American values.

Many of these commentators took the opportunity to note Americans’ well-demonstrated ignorance of even basic facts about their history and institutions. A host of measures — most prominently the annual poll conducted by the Annenberg Public Policy Center — have shown that most adults can’t name the three branches of government, don’t recognize prominent political leaders and mistakenly believe that illegal immigrants have no rights under the Constitution.

Whether out of embarrassment at those results or concern for the lacerating tenor of contemporary political discourse, enterprising leaders have responded in force. Teachers are building out their schools’ civics offerings. Scholars and philanthropies are brainstorming programs to help students spot and debunk the myriad sources of fake news. And a slew of states between Washington and Florida have either considered or adopted measures to direct more resources to civics in schools, at both the K-12 and postsecondary levels.

Massachusetts is only the latest state to join a nationwide push to teach kids more about the U.S. government and their relationship to it. But even with a growing movement to draw attention to the subject, the news is still clogged with more bad omens than good. The latest, a Presidents Day poll of 41,000 adults conducted by the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, found that a majority of Americans in every state except Vermont would fail the U.S. citizenship exam — the same test that Democracy Prep students have to pass (with a minimum score of 83 percent, as opposed to the typical standard of 60 percent).

Fractured trust: Fractured trust

Voting is a limited window into civic behavior. But how Americans vote — or, more accurately, how we don’t vote — is the easiest way to measure our estrangement from public life.

By the standards of other developed nations, voter participation in the United States has historically been quite low. After peaking in the decades following World War II, turnout steadily dwindled over the second half of the 20th century. Although it has regained some ground since then, roughly 60 percent of eligible voters have opted out of midterm elections since the passage of the 26th Amendment, which granted 18-year-olds access to the ballot in 1971.

Even in last year’s hotly anticipated elections, the once-in-a-century organizing still brought less than half of eligible voters to the ballot box.

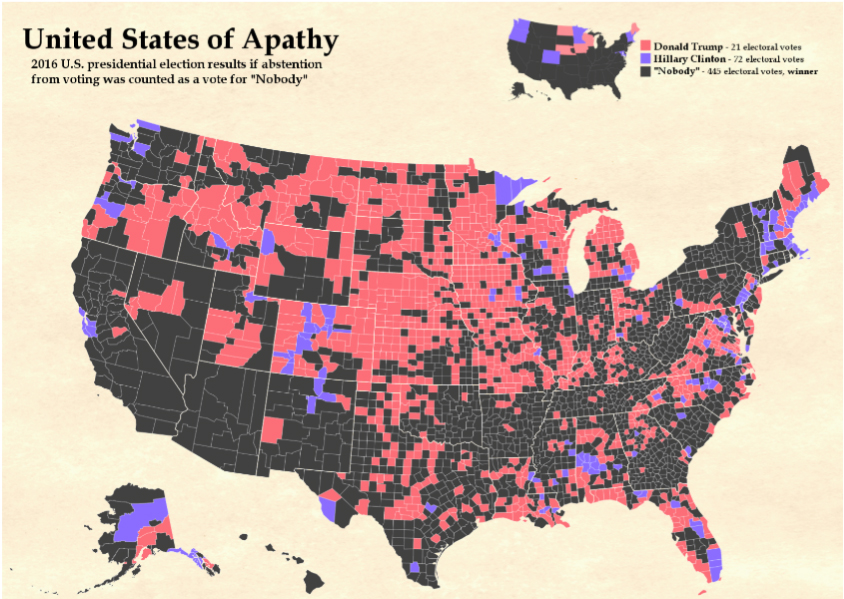

A county-level turnout map created by cartographer Philip Kearney shows that non-voters formed the largest bloc of adults in hundreds of counties and dozens of states in 2016 — to the extent that, if refusal to vote were counted as voting for “Nobody,” that imaginary candidate would have won 445 electoral votes.

But as Mathematica’s Whitesell observed, showing up to vote every few years is only one marker of involvement in civic life.

“Voter registration, and then actually participating in elections, are very important. But these are two measures that don’t paint a very nuanced picture of the sum of your civic engagement with your community and your participation.”

Widening the perspective does little to brighten the picture. Membership in political parties has dropped substantially over the past 15 years. Church attendance has faded. Americans spend less of their time volunteering than in previous generations. Most of us — particularly the young, the poor and the poorly educated — don’t know our neighbors or speak to them about community concerns.

One of the first intellectuals to point out these trends was political scientist Robert Putnam, whose 2000 tract, Bowling Alone, chronicled the fraying of America’s social bonds through the disappearance of voluntary associations like veterans organizations, political clubs and sports leagues. Those institutions brought neighbors together to address common challenges and collectively undertake the responsibilities of citizenship, from leading Girl Scout trips to picking up litter. In their absence, Putnam found, an atomized polity lost its grip on public life.

Putnam’s fears are shared by Peter Levine, a professor of citizenship and public affairs at Tufts and a founder of the university’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). The center serves as a clearinghouse for research into how young people become activated as citizens and what can be done to bolster their rates of public participation.

A 2016 CIRCLE survey of millennials found that those backing Donald Trump were more likely than Hillary Clinton supporters to say they were politically disengaged. Another poll from the same year, this one conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, found that Trump had a special appeal for Republicans who rarely or never participated in social groups like sports teams, book clubs or PTAs.

He also attracted respondents who said the U.S. “needs a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.”

As Americans have moved away from collective participation, their attitudes about individuals and structures outside themselves have also undergone a radical change. Social trust, the belief that other people are honest and helpful, has shown a decline in recent decades. The atrophying of political trust — the confidence citizens have in their governmental and political institutions — has been even more dramatic.

In 1958, 73 percent of Americans trusted the government to do the right thing at least some of the time, according to an analysis from the American National Election Study. Beginning around the time of the Vietnam War, that portion began to shrink, and it now includes only about one-quarter of the population.

Loss of trust in government — its competence, its responsiveness to citizens’ concerns and, ultimately, its legitimacy — has led in disturbing ways to a disenchantment with democracy itself, particularly among young voters. According to the 2018 American Institutional Confidence Poll, respondents between the ages of 18 and 40 were much less likely to agree that “democracy is always preferable” to other forms of government (55 percent) than those over 64 years old (84 percent). In other studies of public opinion, millennials have shown a surprising openness to rule by technocrats, or even the military, rather than elected officials.

‘You don’t know who’s out there’: ‘You don’t know who’s out there’

Since 2016, questions about the loss of faith in democracy have often been posed in the context of a hazily defined place called Trump Country: the factory floors and greasy spoons where working-class whites formed a bond with the unconventional candidate out of anger at being left behind.

But America’s original left-behind place was the faltering metropolis. The “urban crisis” of the 1960s and ’70s, born of deindustrialization and white flight, saw deadly riots sweep through cities across the country. And though most have recovered from the years of drugs, violence and disorder that followed, the urban poor are still subject to some of the greatest failures of public policy, from law enforcement to housing.

The areas where Democracy Prep schools operate, and the students they serve, have not historically enjoyed access to the heights of government power. Their host neighborhoods — north Baton Rouge, west Las Vegas, the Morrisania section of the Bronx — exist in the shadow of more prosperous environs. Over the period examined in the Mathematica study, 99 percent of the network’s student body was black or Latino, 23 percent spoke no English at home and 76 percent qualified for free or reduced-price lunch (the standard proxy for low-income status in the education world).

Perhaps that’s why the issue of social trust is such a tricky one for Jy’Asia Dunn.

The 19-year-old is a senior at Democracy Prep Harlem High School, one of five the network operates in New York. Located on West 120th Street in Manhattan, Harlem High is a fair distance from Jy’Asia’s home in the Highbridge neighborhood of the Bronx. Though she doesn’t mind commuting for what she calls a “very rigorous” education, she says she’s late most days — school starts at the oddly specific time of 7:43 each morning — and not just because of the oft-malfunctioning B subway line.

From her home, the quickest route to the train is across a set of crumbling stone steps connecting Anderson and Jerome avenues. After dark, locals steer clear of the passage, screened by overgrown trees and strewn with litter. Neglected for decades, the stairs have become a magnet for crime; a 2012 article for DNAinfo recounted neighborhood leaders’ repeated and unsuccessful appeals to city officials to have the area cleaned out. But more than six years later, the stairs remain dilapidated as ever.

“It’s hard to get here on time and safe,” Jy’Asia said. “It’s so dark in the morning, and you don’t know who’s out there. Recently, someone died over there. Someone got shot. I’d rather wait till the light comes outside, and more people are outside, than to be on time to school. I’m not going to put myself in danger to be walking through the dark.”

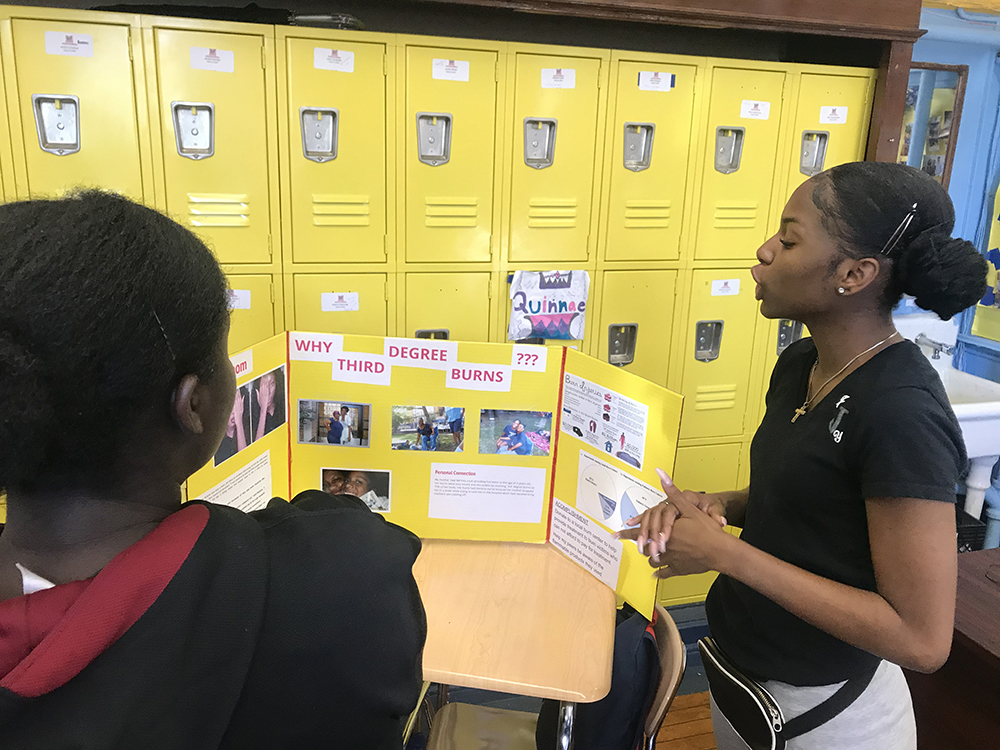

She’s close to her friend and classmate Deasha Gilmore, who also hails from Highbridge. This year, they’re collaborating on the assignment that represents the culmination of Democracy Prep’s civics curriculum: Change the World, a yearlong project that takes civic learning out of the classroom by engaging seniors in research and direct community action.

The girls are teaming up to lead an awareness campaign about burn prevention. The subject has personal significance for Jy’Asia, whose mother suffered third-degree burns as a child. The injury resulted from an accident in the home involving faulty maintenance, Jy’Asia said.

As a child, Jy’Asia said she was sometimes uncomfortable with the visible damage done to her mother’s skin. Now that she’s nearing the end of high school, she wants to educate others on how to protect themselves from similar pain.

“As I grew up, I was like: This woman is beautiful. This woman’s my mom, and I love her so much. I just wanted to show the world how beautiful she is, and how to prevent burns.”

For all the ways it has changed over the past few decades, New York is in some ways the same city Jy’Asia’s mother grew up in. Rents are coming up quickly in Highbridge, but it has long been one of the poorest corners of the city. Just a few subway stops away from gentrifying West Harlem and Washington Heights, the neighborhood’s children grow up amid crime, shoddy infrastructure, and unstable and unsafe public housing.

Education options haven’t been a historical bright spot, either. Local elementary school P.S. 64 was phased out three years ago after ranking among the bottom 1 percent of schools in the city. After years of Highbridge having no middle school of its own, frustrated parents had to wage a years-long campaign to plan and open one themselves.

The world that Highbridge residents see reflects the inequities that pervade American society, and their influence over the conditions shaping their lives is drastically limited compared with that of more advantaged New Yorkers. Experts on American civic life have come to refer to this basic inequality as the “civic empowerment gap.”

The civic empowerment gap: The civic empowerment gap

No one has written more prominently on this phenomenon than Meira Levinson, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education whose 2011 book, No Citizen Left Behind, detailed the massive disparities in democratic participation between the white, educated, affluent and native-born versus the non-white, uneducated, poor and (often undocumented) immigrants. Levinson finds that people who earn more than $75,000 a year are up to six times as likely to work on a political campaign, participate in a protest or reach out to an elected official as people who earn less than $15,000.

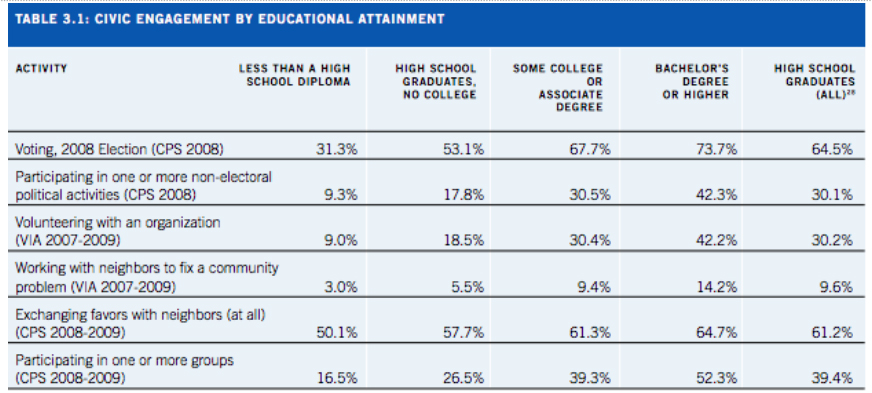

In its 2010 report on civic life in America, the Corporation for National and Community Service demonstrated the same gaps. Though race, class and immigration status were all associated with different levels of political activity, no variable was more determinative than educational attainment. Bachelor’s degree holders, the study found, were more than twice as likely to have voted in the 2008 election as those without a high school education; more than four times as likely to volunteer with an organization or take part in political activities besides voting; and more than three times as likely to take part in one or more groups.

Not only do the more advantaged enjoy much greater political participation (and with it, far greater political influence), their children are also better schooled in civics and politics as well.

Last year, the Brown Center on Education Policy’s annual report on American schools focused specifically on civics education. The study tracked standardized test results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), sometimes called “The Nation’s Report Card.”

Two decades of scores provide a bleak picture: Gaps in civic knowledge between white and black students, white and Hispanic students, and middle-income and low-income children have not shrunk during the era of accountability-based reform that began with the 2001 passage of No Child Left Behind. In fact, they’ve actually widened.

Scores from the 2018 NAEP civics exam will be released this fall, and few expect these trends to be reversed. Some even claim that, by fixating stubbornly on math and English performance, NCLB undermined attempts to improve civics education. Since what gets tested is what gets taught, they argue, instruction in the two core subjects crowded out classroom time for science, art, music and civics.

Though this theory is common among educators, not everyone agrees. In a 2009 study for CIRCLE, Tufts’s Levine found that NCLB didn’t result in lost instructional time for civics at the middle or high school levels. In some cases, he wrote, the percentage of older students taking courses in liberal or performing arts even grew in the years following the law’s passage.

Still, Harvard’s Levinson said there’s some truth to the idea that schools care less about civics education now than in 2001.

“I think that No Child Left Behind narrowed what people cared about, what they were held accountable for,” she said. “Certainly, it focused entirely on literacy and math for the first years, and then built in science. It is quite clear that, say, social studies instruction in general — and civics instruction as part of that and also as its own thing — simply got sidelined.”

But Levinson believes that federal education law is not the primary driver of America’s shift away from civics education, which she says began decades before the dawn of the testing era. But given the nation’s slump in civic engagement, she says, it’s crucial for schools to rededicate themselves to teaching the subject effectively.

“Good civics education actually does make a difference, and we have fewer civic-educational institutions elsewhere in society now,” she said. “Part of the reason for the civics education crowd being in favor of civics education is because there’s pretty good evidence that it can make a difference, and that it’s more needed to make a difference.”

‘An obvious solution’: ‘An obvious solution that will make no difference’

Given Americans’ growing skepticism of their political system and governmental institutions, and the widening gulf in civics knowledge and participation along lines of race and class, it comes as little surprise that many states are rushing to add civics content to their K-12 curricula. Many cite public education pioneer Horace Mann, who argued that the first aim of schooling should be to prepare children for the duties of citizenship.

Indeed, the National Conference of State Legislatures has found that 115 bills and resolutions pertaining to civics education were introduced in 31 states during the 2018 legislative session, of which 15 were adopted. That counts as something of a deluge for a niche policy area that has traditionally been favored by the earnest and the academic.

Even before Massachusetts enacted its reforms, the state of Washington became the 42nd state to mandate at least one semester of civics coursework as a high school graduation requirement. In an April 2018 press release touting the new law’s passage, its primary sponsor said she hoped that more classroom instruction would help combat “this age of ‘fake news,’ social media, distrust of government and misunderstanding of process.”

Though the pivot toward civics education has occasionally taken an anti-Trump tack, Republican-leaning areas have gotten into the game as well.

Most prominently, 18 states have adopted a requirement that all public high school students take the U.S. citizenship test, just since 2015; eight of them require students to pass the test in order to graduate. The sudden progress on that front has followed intense lobbying from the Joe Foss Institute, an Arizona nonprofit whose former president, Frank Riggs, was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for state superintendent in 2018.

Former Republican Indiana governor Mitch Daniels, now the president of Purdue University, has called for undergraduates to take the test as well, saying he was dismayed by the lack of civics knowledge among students who should have picked it up in high school.

While cheered by the newfound attention to the subject, some of the field’s experts are left cold by simple calls for more butts in civics seats. The citizenship exam is a case in point: While its tougher questions may flummox some test takers (Are you sure you know what year the Constitution was written?), most students will surely memorize the answers and forget them later.

Requiring that students take the test to graduate is “a classic case of what seems like an obvious solution that will make no difference whatsoever,” Notre Dame’s Campbell said. “I wouldn’t say we have any reason to think it would make much difference. And the reason for that is just giving kids a test is not really going to have much effect on them.”

Indeed, among some of civics education’s most passionate advocates, there is something of a debate over just how worried we should be about Americans’ inability to rattle off civic and historical facts. As some have pointed out, high schoolers flunked U.S. history tests throughout much of U.S. history, and it’s likely mistaken to believe there was ever a halcyon era of civics instruction.

“We’re in a crisis, but it’s not a crisis of declining knowledge of the system of government,” Tufts professor Levine said. “I think the crisis has to do more with certain features in our republic, like our inability to talk about issues with people who disagree or our inability to sort out reliable news from unreliable news … The republic is in some danger, and we have a different set of challenges than we used to have.”

Political scientists have raised concerns about online “filter bubbles,” the social media feedback loops we construct to insulate ourselves from opposing political views. Not only does our lack of exposure to contradicting ideas limit our capacity for personal and intellectual growth — it also makes it easier for us to be taken in by narratives that flatter our existing beliefs. Studies of high school and college students have shown that many are utterly unable to tell legitimate news and reference sources from slick marketing or editorial content from ideological sources.

Levine doesn’t gainsay the benefits of more class time spent on civics instruction (“I would say, pretty much, the more the better. … We’re not anywhere close to worrying about too much time on civics”), but he principally values that time as a chance for pointed, but cordial, disagreement on current events, politics and American ideals.

“Here’s my big point: We have to be tolerant of a little bit of politics in our schools, including the politics we don’t actually like. Otherwise, we throw the baby out with the bathwater and we basically have everything, we have politics-free zones. That’s a bad way to grow up. As a liberal, I am OK with some conservative teacher indoctrinating the kids if it means that there can be some discussion of politics in the schools.”

There is a danger in the political verging toward the partisan. Teachers often tread a narrow line when introducing controversial topics of discussion, and parents are quick to complain of political advocacy in the classroom. The concern has grown to the point that, over the past year, lawmakers in Arizona, Pennsylvania and Maine have all introduced bills to prohibit forms of political indoctrination in schools.

Yet the power of open debate is documented in research: In a 2005 working paper for CIRCLE, Campbell drew on survey and assessment data to show that students who experienced an open classroom environment — i.e., one characterized by frequent, respectful conversations about contemporary political issues — were both more knowledgeable about civics and more likely to report that they would be informed voters someday.

“Politics is fundamentally about conflict,” Campbell said. “So what a good civic education needs to do is teach all of us, the young or old, how to deal with conflict so that we don’t just shy away from it and ignore it, but actually engage in it. And that means we have to expose kids to the cut and thrust of politics. If you don’t, then we will have not prepared them for the world in which they really live.”

The levers of power: The levers of power

If you’re hoping to dig into a contentious debate, inequality and class warfare is a pretty good place to start.

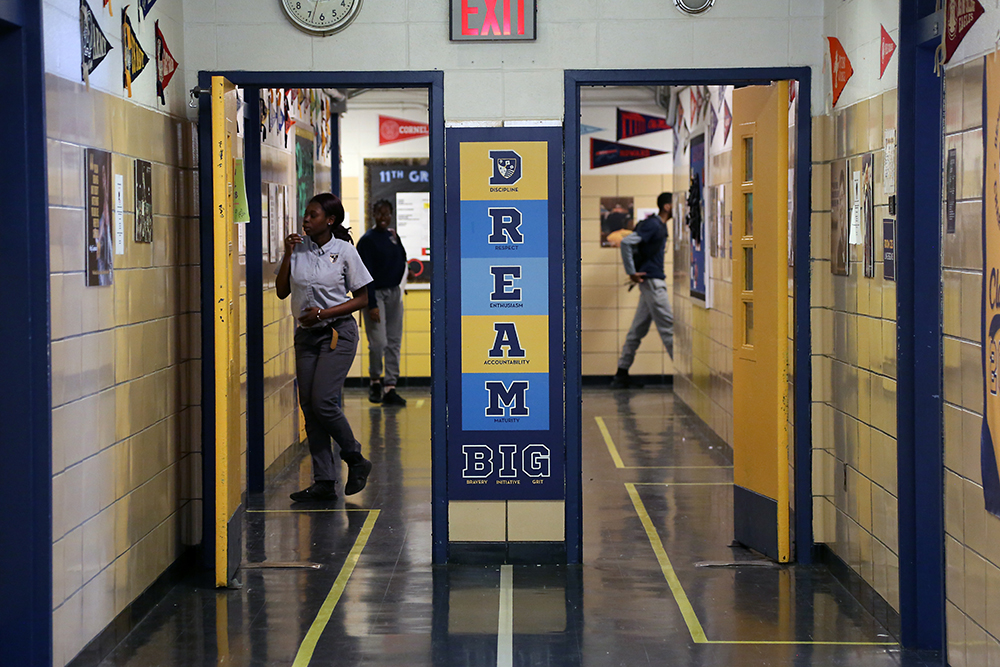

In a third-floor classroom at Democracy Prep Charter High School in Harlem, Jillian Powers is trying to impress upon the class of 2019 the importance of a half-forgotten episode that unfolded eight years ago and 175 city blocks downtown. The walls are crowded with posters of activists and leaders — Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela, Louis Brandeis — extolling the value of grit and initiative.

Powers teaches Charter High’s Seminar in American Democracy, a yearlong class that all Democracy Prep seniors take in order to graduate. The course aims to highlight the fundamentals of the U.S. system of law, government and economics through discussions of current events. Her classes this year, held every other Friday, have touched on multiculturalism, gentrification and the recent repeal of New York City’s weirdly draconian cabaret law.

Today she’s leading a class on economic inequality, with a focus on both Occupy Wall Street and Amazon’s recent decision not to build a second massive headquarters in Queens.

All the students are familiar with the Amazon reversal — most of them shop from the internet retail monolith, or at least stream its television shows — but Occupy is a bit more obscure; even though they live less than a dozen miles north of the Financial District, most of them were starting fourth grade when the first tents were pitched in Zuccotti Park in 2011.

By way of context, Powers scrawls a few figures on the whiteboard: Between 1979 and 2007, income for the top 1 percent of earners grew by 275 percent. Ninety-five percent of the income gains between 2009 and 2012 were achieved by the same 1 percent of earners. Yet millions of American children live in poverty.

That level of inequality hasn’t been seen since the Gilded Age, she tells the class. Why might it be a problem for democracy?

Farhan Mehsud raises his hand. Polite and soft-spoken, Farhan is headed to New York University in September. His favorite subject is math, but with his tendency to speak in paragraphs, he’d likely make a good essayist.

“The democracy that America attained during the founding era was due to the common men, who weren’t rich people. They were farmers. With their voices, change was able to be brought. But now, the 1 percent are the ones who are making most of the decisions, and that goes against the fundamental principles of democracy that our country was built upon.”

The seminar continues from there, zigzagging between questions of economics and political theory: Can the Amazon deal, struck between a handful of city officials and the world’s richest man, be the product of a truly democratic system? Why do we have a representative democracy, anyway, rather than a direct one?

The conversation settles on the organizing tactics of Occupy Wall Street, which tended toward the anarchic. Powers compares the campaign’s shortcomings with those of the Young Lords, a ’70s–era human rights group whose influence was limited, she notes, because they “didn’t want to work with the politics.”

Another student, Cheikh Fall, jumps in. If you’re not willing to pull the levers of government and politics, he says, no one’s going to take you seriously. The capacity to work the system — both from within and without — is what Democracy Prep aims to instill in its graduates through years of practice in civic participation.

“You’re not making any change, so you’re basically doing this for nothing,” he says. “’Cause if you just say, ‘I’m going to change the system, but I’m not going to work within the system to change it,’ the system is going to remain the same. And you’re just going to be that outlier who sits there and pretends that you’re changing something. In reality, you’re not really changing anything, because the system is still run by the same people.”

“So what’s your purpose?”

This article was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter