How Democracy Prep Is Drawing Upon Civics to Challenge Its Students to ‘Change the World’ — Before They Graduate

By Kevin Mahnken | April 10, 2019

At a time of widespread apathy, these high schoolers are using what they’ve learned to make real change in their communities via a nine-month senior capstone project that prioritizes civic engagement

Djeneba Sy has a way of standing out from the crowd, even one as hectic as this.

The senior at Democracy Prep Harlem High School stood smiling behind a desk in the crowded fourth-floor classroom, ready to explain the details of her yearlong capstone project. A few students thronged around her as others squeezed past. Like her classmates, she introduced herself and gestured toward her visual aid, a foldable display board covered in quotes and statistics about the research she’d conducted this year.

Unlike the other seniors, she was clad in her cheerleader uniform for the Democracy Prep basketball team’s homecoming game later that day at nearby City College. Her subject, depression and mental illness, was a grim one, but she cut an especially — well, cheerful figure in the school’s trademark blue and gold. A bow sat atop her already elaborately styled hair.

She led off with a bracing motto: “Face your problems rather than running away from them; otherwise, they’ll build up over time.”

Djeneba was addressing a few members of the school’s junior class, which had been broken into small groups and circulated through five classrooms on the building’s top floor. Boston College (all the classrooms are named after colleges and universities) was full of about 12 seniors, each telling a few 11th-graders about their projects. There was just enough time for their listeners to absorb the presentation, ask a few questions and share their thoughts before moving to the next desk.

After 10 minutes, an alarm went off, the audience rotated to the next classroom and a new group of juniors trooped in. Some looked dazed.

Change the World projects like Djeneba’s are a fixture at Democracy Prep high schools, the most ambitious expression of an organizational mission that has been developing over the network’s 13 years in operation. Along with preparation for college-level academic work, the organization — 21 charter schools spanning New York and four other states — aims to equip students with the knowledge and skills for a lifetime of active citizenship.

Change the World is the culmination of the network’s civics approach, a rite of passage that sees 12th-graders launching hundreds of small-scale social enterprises each year. By raising money, organizing demonstrations, hosting guest speakers and building advocacy groups, the seniors have a chance to put what they’ve learned about activism and community engagement into practice. It’s a method that the school believes will ultimately yield energetic, responsible citizens — and possibly act as an antidote to the grim state of democracy today, in which too few Americans are prepared to cooperate to solve major problems facing their communities.

The controlled stampede this January morning was the brainchild of Amrita Khalsa, the Change the World coordinator at Harlem High. She oversees the projects and teaches the senior class a semester each of sociology (with a special emphasis on the development of social change) and economics.

Over the course of their senior year, Khalsa helps her students identify a social problem, whether in the school, their hometown or the world at large. They write a research review examining the roots of that problem, design and implement some method of combating it, and measure the impact of their solution. To complete the assignment, the students have to defend their findings before a panel of three faculty members.

The fourth-floor pitch fair was functioning like a soft opening. The juniors — who will be doing the same thing this time next year — gave constructive criticism and ranked the pitches they listened to, with the highest-rated being announced later in the day.

Before leading them upstairs, Khalsa gathered the juniors in the school cafeteria to set expectations.

“I want to see their Change the World projects come out really great, but I’m also going to need the feedback from you guys,” she said. “Really push the 12th-graders: ‘Why did you choose this topic? Why is it so important? What are your plans for this project? How are you going to do this?’”

The scene on the fourth floor resembled a kind of social consciousness trade show. Dozens of projects were described, covering a truly staggering variety of causes: gender equity in sports, child abuse, sanitary food practices, inclusivity in beauty and makeup products.

And, of course, mental illness. Speaking to a girl in a red hoodie, Djeneba had to use her cheerleading voice to be heard above the din of mottos and action plans.

American adolescents are suffering from soaring rates of mental health problems, she explained. In a recent Pew poll, 96 percent of U.S. teens said depression and anxiety were problems for people their age — higher than bullying, drug and alcohol abuse, teen pregnancy, poverty or gangs. With her classmate Brandon Arthur, Djeneba created her own survey to measure psychological well-being across the student and staff populations at Democracy Prep.

After retrieving the data, their plan is to invite a psychologist or social worker from the charter network to lead a panel on mental health awareness. They hoped the session would include “flash counseling” sessions, allowing both teenagers and adults to voice their doubts and worries.

Djeneba said she hasn’t personally dealt with depression. But people close to her have, and she’s concerned about widespread public ignorance of the causes and manifestations of mental illness.

“Growing up, I witnessed my friends go through [depression]. In middle school, there was this girl who went through it. I didn’t know how to help, so I kind of stayed away. It’s like you’re watching it on TV — what can you do? That’s what made me want to pick depression. I want to know more so I can help.”

Her pitch concluded, she paused for questions. Before moving on to the next desk, the girl in the hoodie stopped and reached in for a hug.

The knowledge divide: The wrong side of the knowledge divide

To Viviana Perez, who coordinates civics programming throughout Democracy Prep’s far-flung locations, the nine-month slog it takes to produce Change the World projects every year captures the essence of what the network is attempting to achieve.

“It mirrors real life,” she said. “Oftentimes, we think about our education not giving us practical skills. The Change the World project asks the students to actually think about something that they are passionate about, a societal ill that they might see in their community, and figure out, ‘What can I do to resolve that?’”

According to a recent study, which found that Democracy Prep graduates are significantly more likely than their peers to vote and to be registered to vote, the network seems to be succeeding in its aim of activating students as democratic actors.

That success has come even while Democracy Prep mostly serves kids who start on the wrong side of the knowledge divide. Scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as “The Nation’s Report Card,” clearly show low-income and minority students falling further behind in civics.

With schools located in New York, Camden, Baton Rouge, San Antonio, and Las Vegas, its 6,500 students are 99 percent non-white. Eighty-five percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a common proxy for low-income status.

Natasha Trivers, Democracy Prep’s superintendent and interim CEO, said the country can’t afford civic disillusionment from any corner.

“Absolutely, I’m concerned that we’re getting to a place of civic decay, to put it in the most dire terms,” she said. “I think disenfranchised young people anywhere — even if they are of some means and privilege — is a problem. People who are afraid and feel left out of the conversation are a problem. That’s not how our democracy is meant to work.”

Yet even with a view toward the bigger picture, it’s easy to be struck by the obstacles facing many of Democracy Prep’s students. Trivers herself attended public schools in New York City. The disorder and violence in her environment made it difficult to imagine shaping it for the better. She was mostly trying not to disappoint her mother, a Jamaican immigrant working two jobs to make ends meet.

“Frankly, a lot of what I spent my time doing is sort of building a façade so that I could look tough enough to walk to the bus stop and go to my school,” Trivers said. “I also didn’t push myself to be a scholar that was getting straight A’s. I didn’t see a value in that. It was a pretty discouraging time where I was like, ‘I’m not really sure what I’m supposed to be doing except for surviving.’”

Today, she said, “I see a lot of myself in my students. We have a fair amount of students who have emigrated from West Africa, students who are navigating how to pursue the American dream.”

Change the world; act locally: Change the world; act locally

Samantha Hernandez has been in pursuit for over a decade. A senior at Democracy Prep Charter High School — one of Harlem High’s four sister high schools in New York — she has been on a journey that has taken her across both national and district boundaries, and will soon see her enrolled in college.

Samantha’s mother brought her to the United States in 2006 from Nagua, a low-lying town in the northern Dominican Republic known for producing rice and coconuts. She was just 5 at the time; the early stages of the transition, she now remembers, were a “bumpy road.”

Samantha, her mother and her little brother shuttled between working-class neighborhoods in the Bronx. She was a good student from a young age and by eighth grade was completing high school work a year ahead of schedule. Her teachers were soon advising her to transfer elsewhere, since her own school didn’t offer the Advanced Placement classes she would likely require as the years passed.

But the district school she enrolled in for the following year, which putatively had a focus on law and public policy, was far worse. The school culture had given way to chaos, with drugs and violence in abundance. She said that she “knew who not to mess with” but that her worries made it impossible to focus academically.

“I felt so frustrated that I actually did worse in school because I couldn’t concentrate,” she said. “There would be times when I didn’t want go to class.”

Samantha left for Democracy Prep after ninth grade. From her home in the South Bronx, she commutes nearly an hour on the subway just to reach Charter High each morning. But the difference in learning environment makes the haul worth it, she said. While she says the charter’s disciplinary standards can take on a “military” cast, she has peace of mind there.

The international roots of families like Samantha’s have led some Democracy Prep seniors to view Change the World through a global lens: Several recent projects have been devoted to sending aid to Africa or the Caribbean for school supplies, or supporting the work of overseas missionaries.

But for her project, Samantha is attempting to alleviate a long-ignored problem in her own backyard: raising funds to buy and distribute hygiene products for homeless women. Homelessness is a common subject of Change the World projects — New York City’s estimated unhoused population numbers nearly 80,000, and Samantha encounters desperately poor people on her way to and from school every day — but she wanted to focus on an aspect of the problem that she believes doesn’t get enough attention.

Discovering the precariousness of women who couldn’t access necessary supplies gave her a shiver of recognition, she said.

“There were a lot of times where I was alarmed because I’m a woman myself. … Those thoughts wouldn’t go through your head — that people need basic necessities, and when they’re homeless, they don’t have security over those [necessities].”

Filming the foster care crisis: Filming the foster care crisis

Many Change the World projects draw on personal experience. When Nyashia Hughes was in elementary school, her cousin’s mother died, breaking up the home. Nyashia’s mother tried to take the boy in, but ultimately the cousin was “lost in the system,” Nyashia said; to this day, she doesn’t know what became of him.

The searing experience fueled Violet, a 15-page melodrama centered on the failures of the foster care system. The system serves nearly half a million American children. Most struggle to get anything approaching a decent education, and far too many carry the wounds of childhood abuse and abandonment.

On a Friday afternoon in early March, Nyashia Hughes asked a handful of friends to make the ultimate sacrifice for her Change the World project. As the winter weather began to thaw in Harlem, she recruited them to stay after school to help her shoot her first movie.

Nyashia said the few media depictions of foster families have contributed to damaging negative perceptions about the challenges of kids whom society has largely given up on. Those stereotypes can scare off prospective parents.

“People believe that if you bring a foster child in, it will cause a lot of drama,” she said. “It will take a lot of time. You’ll go through a lot of money, and of course money is necessary because it’s a child. You are taking care of a life.”

On the distinctly no-fuss set — the scenes are shot in Democracy Prep classrooms and offices, on a single tripod-mounted camera — Nyashia gave direction to the classmates she selected to play Violet, a teenage girl who has moved among multiple foster homes, and her teacher. In the scene, the teacher notes his concern that Violet’s grades are dropping; she responds that she’s nervous about becoming too old for a family to adopt.

It’s a wrenching moment that Nyashia insisted on capturing in multiple takes from different angles. Violet will be her cinematic debut, but if she experienced any butterflies, she hid them beneath a veneer of chirpy confidence. She even storyboarded what she wanted the shoot to look like (although, she conceded, “it looks horrible because I can’t draw”).

“I have a vision for everything,” she said. “I know how I want things set. I already even thought, for when I go into editing, how I want some things to be filtered. Some scenes should be filtered differently to show different emotions within the characters.”

Lisa Kowalski, the drama teacher who is overseeing the project, began to tap her watch, and the shoot broke up for the weekend. The kids seem to have enjoyed themselves, and Nyashia will get her first directing credit, but Violet’s somewhat bleak story is what she’s focused on most. Just 17, she knows already that she wants to be a foster parent, and the stories of kids languishing in foster care seem to haunt her.

“Most of the time, it comes from drug abuse with previous families or their own family or just the things that they had experienced in group homes. A lot of kids who are foster kids end up in juvie and things like that. So, they have a lot of things that impacted them in the past that people don’t necessarily focus on. They just focus on the things that are occurring … now, so that kind of creates that negative perception.”

‘Action civics’ or advocacy?: ‘Action civics’ or advocacy?

Change the World fits squarely into an educational philosophy known as “action civics.” At its most basic, action civics simply means engaging students in direct, change-driving work aimed at solving real-world problems. But at its most extreme, critics say that it veers into activism, pointing to the increasingly common sight of students leading walkouts to protest gun violence or joining their teachers on picket lines.

It’s on that last point that a number of education reformers — particularly on the political right — begin to get queasy. Some have spent years banging the drum for more civics content, pointing to Americans’ woeful ignorance of their government and history. But they are uncertain about the recent vogue for action civics.

Robert Pondiscio, vice president of external affairs at the right-leaning Fordham Institute, said it’s absolutely right to teach students what government does — and even what steps to take to get government to do what they want. But to prod them to think of themselves as activists is to cross the line into advocacy.

“Once you start talking about shaping a kid’s attitude and beliefs … as a deliverable for their education, then I get uncomfortable,” he said. “I want them to have civic knowledge and skills, and what they do with them is up to them. It may sound anodyne to say that children should have a commitment to social justice, but it’s really not. That’s a political stance, and that’s the type of language, I think, that gets conservatives’ hackles up a little bit.”

That’s led prominent reformers like Chester Finn, Pondiscio’s Fordham Institute colleague, to warn that class time is being lost to protests that flirt dangerously with partisanship. When teachers led a group of California students to Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s office in March to forcefully advocate for her to support the Green New Deal, Pondiscio complained that they were being used as “political props.”

“If all you’re doing in your action civics projects is doing things at the direction of other people, then you are not fully citizenship-ready,” he said. “You are not prepared to exercise your own agency as a citizen. You are prepared only to march in somebody else’s army, and that is just not, by my standards, good enough.”

Pondiscio has written prolifically about the need for more civics instruction, sometimes opining that students should be able to pass the U.S. citizenship test by the end of elementary school. He has also worked with Democracy Prep in the past teaching American democracy to seniors at Harlem’s Democracy Prep Charter High School. The course is meant to run parallel to the students’ Change the World projects, generating discussions about fundamental issues of the constitutional system in the context of current events.

When, in 2015, one of his students organized a “die-in” in front of a local police precinct house to protest police brutality, Pondiscio had him construct a brief on how law enforcement policy — from training on the use of force to mental health services — might be changed to make police more responsive to people of color. Would these changes need to be pursued at the state level, or the municipal level? Who would be the decision maker to pressure, and how could that person be persuaded?

Overall, Pondiscio said that he “loves” Change the World projects and considers the coursework associated with them to be worthwhile. The U.S. citizenship test is, in fact, a high school graduation requirement at Democracy Prep, and Change the World is only the most active facet of a network-wide civics program that includes classroom investigation of the contentious issues of American history and government. But as more states enact new mandates around civic education, Pondiscio said he hopes that students will be equipped with not only an activist spirit, but also the basics of American democracy.

“It’s one thing to march in a protest, and that’s OK, but now the other part is, ‘How do I learn where those levers are, and how to pull them?’”

Social justice focus: Social justice focus

At Democracy Prep, the study of American government and history isn’t confined to one class during senior year, or even one course of study. An element of citizenship education underlies even seemingly unrelated subjects.

“Even our Algebra 1 teacher working with the kids is like, ‘Let’s look at Census data and talk about the trends we can pull out as we’re practicing writing formulas and graphing things. Let’s talk about social justice. Let’s talk about populations and wealth and what that looks like across different neighborhoods in New York City,’” said Ashley Getting, who teaches the Change the World curriculum at Charter High. “That’s such a focus of our curriculum, everything’s tied back to that social justice and civics model. I loved that coming in.”

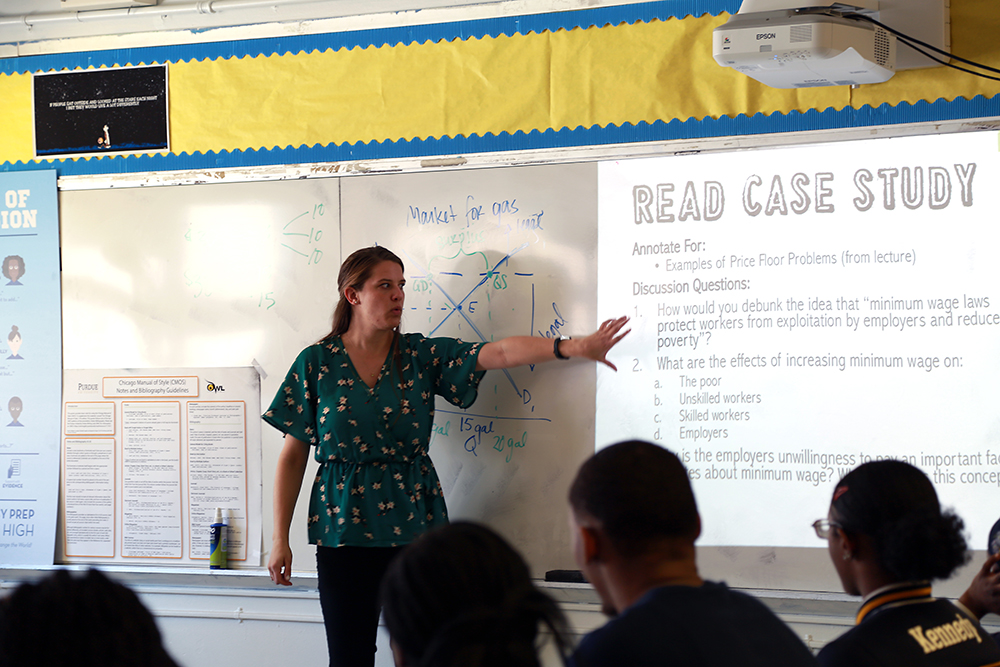

Now in her sixth year, Getting serves as the history department chair at Charter High, where she coordinates the progress of students’ projects. In the classroom, she teaches one semester of Sociology of Change, looking at the progress of social movements over time, and one semester of economics. Her syllabus touches on a range of historical episodes, both domestic and international, with obvious relevance to contemporary politics: So far this year, she has taught units on the origins of gerrymandering and apartheid rule in South Africa.

Getting says that one aim of the course is to disabuse students of the notion that persistent social problems can simply be solved by an all-powerful government.

“We start off the year with an analysis of systemic change — what it takes to change systems and institutions — basically to get them thinking, ‘OK, government can’t do everything; it’s too large and slow. So what do we need to do individually?’”

Sociology of Change also gives her the freedom to try new ways of approaching familiar subjects. This year, she has begun integrating study materials from Harvard Business School’s Case Method Project, a clearinghouse of academic simulations that put students in the role of historical decision makers at critical episodes from America’s past. Some force them to consider Lincoln’s perspective during the secession crisis, or to weigh the benefits of passing the Equal Rights Amendment in the early 1980s.

To close out this year’s course, Getting chose a case devoted to Martin Luther King and the origins of black suffrage in the South. Her seniors spent four classes discussing the legacy of disenfranchisement after Reconstruction, the long era of disinvestment and exclusion leading into the 20th century — and then the first stirrings of black economic and political power decades before King gained a national platform.

During one lesson, Getting divided the class into discussion groups around a few desks to consider the social changes unfolding over the first decades of the 20th century, including the tactics of early activists. In one group, a debate broke out over the intentions of policy makers at the time — by slowly improving the quality of life of African Americans during and after World War II, were they hoping to build a more fair social order? Or throwing crumbs to keep a mistreated caste from demanding more?

Cheikh Fall, a senior who emigrated from Senegal just six years ago, said he believed that the era’s reformers were sincere in their efforts to end injustice but didn’t push hard enough to achieve integration.

“I think their focus was more helping black people, not making sure that blacks and whites could coexist,” he argued. New high schools, hospitals and housing developments were a boon to the black community, but they stopped short of the full inclusion that was needed.

“Instead of actually ending segregation, they were just making blacks more comfortable,” he said.

From across the desk, Cheikh’s classmate Kennedy Douglas cut in. Whites held all the cards and could have brought about a truly integrated society, she said, but it took decades for an activist movement to force their hand, from Brown v. Board through school busing. “If they really wanted to end segregation, I feel like it would have happened back then.”

Getting, moving between discussion groups to prod with more questions, addressed Kennedy directly. “So why did it take so long to get there?”

“It’s still not ended,” she answered.

Becoming ‘better citizens’: Becoming ‘better citizens’

Brandon Arthur doesn’t take Getting’s class — he’s a student at Democracy Prep Harlem High School, Charter High’s sister school 14 blocks to the south. But Brandon, who is collaborating with his classmate Djeneba to implement a Change the World project focused on depression, views the conditions of African-American life in 2019, including the issue of mental health, through the lens of history and power.

“In the black community, we experience a lot of depression, we experience a lot of mental illnesses that are kind of generational; they’re, like, handed down to us from our ancestors,” he said.

Asked to elaborate, he made the connection more explicit.

“We were oppressed, and we were also depressed, right? There’s a lot of resentment in our community, and I feel like … some people feel like they can’t get above where they’ve been and where they are now because of their skin color. They don’t necessarily know how to express that, so it just bottles up and it becomes depression, or it becomes some sort of outrageous behavior that they can’t even explain themselves, because they don’t have the tools.”

Tall and comfortable speaking off the cuff, he said he wants the black community to open up more about the mental health struggles that it is disproportionately vulnerable to: Statistically, African Americans are much more likely than whites to suffer from depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Unlike Djeneba, he said that he has experienced bouts of depression himself, along with others in his family. That wasn’t helped by his early feelings of being “different” — Brandon is openly gay, which he said hasn’t been easy in the part of Harlem where he lives.

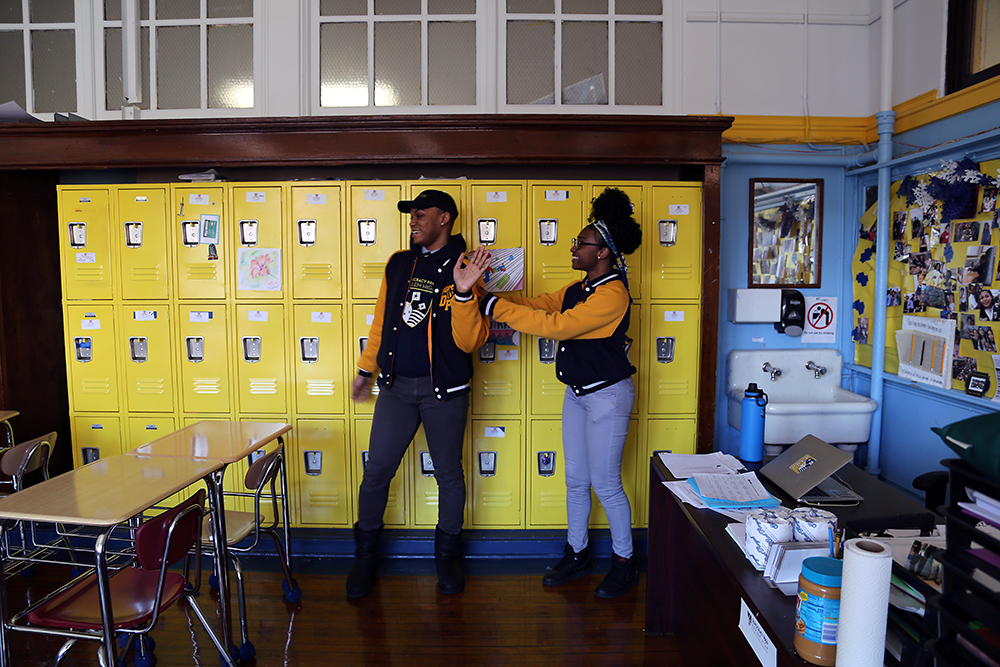

Students are meant to implement their projects in the spring, then collect data on their impact and present them to a faculty panel for a final assessment. In mid-March, Brandon and Djeneba were still partway through their project, having already administered a survey to more than 100 students and staff asking about their mental health. The poll inquired about specific stressors, such as sex, social media and gender identity. Brandon said the results changed the way he looks at the school community.

“We got a lot more responses about sexuality than I thought we would because everyone seems so content in who they are here,” he said. “I was like, ‘Wow, people are going through similar struggles to myself,’ so that kind of shocked me.”

The typical pressures of adolescence would be enough without wondering about what comes next. Both Brandon and Djeneba are waiting to hear back from colleges, and the uncertainty of the admissions process has begun to take its toll.

Sitting beside Brandon, Djeneba became emotional while describing what it would mean to her to start college in September. Neither of her parents, immigrants from West Africa, finished high school.

“I am a little stressed because my parents, they dropped out of school, 11th grade, back in Mali, and that’s when they came,” she said, beginning to tear up.

For the moment, both are excited to consider the future. They said that their time at Democracy Prep has prepared them for college-level academic work. But Brandon added that he feels the school has made him a better person: more attuned to the problems in the world, and more ready to find solutions.

“If you don’t have knowledge of a situation, you’re really not going to know what to do when you get there. DP gives us the knowledge and the experience that we need to join everyday politics, because we are in a group [that’s] kind of marginalized. … So DP giving us this opportunity to get out to vote — to try to encourage people amongst our community to vote — it makes us better citizens. It makes us educated citizens, and education is power.”

This article was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Disclosure: Kevin Mahnken worked with Robert Pondiscio as an associate editor at the Fordham Institute from 2014 to 2016.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter