74 Interview: Researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings on Culturally Relevant Teaching, the Role of Teachers in Trump’s America & Lessons From Her Two Decades in Education Research

See previous 74 interviews: Sen. Cory Booker talks about the success of Newark’s school reforms, civil rights activist Dr. Howard Fuller talks equity in education, criminologist Nadine Connell talks about the data behind school shootings, former U.S. Department of Education secretary John King talks the Trump administration and more. The full archive is right here.

Gloria Ladson-Billings remembers that there was a difference between the black and white teachers she had growing up in Philadelphia.

African-American teachers could give the students “the talk,” she recalls, referring to a 2017 Procter & Gamble television advertisement that showed black parents talking to their kids about racism. The black teachers could speak to students honestly about what it means to be African-American in a way their white counterparts never could, she remembered.

Ladson-Billings speaks often about her fifth-grade teacher, Ethel Benn, who first taught her about W.E.B. DuBois. She was amazed to learn that a black person had graduated from Harvard University, she remembers; at the time it seemed impossible.

Now, Ladson-Billings studies what it takes to be a successful teacher of African-American children and has written extensively about culturally relevant teaching since the 1990s.

Culturally relevant education is more than celebrating Black History Month or offering an ethnic studies class, she said. She has defined three pillars of culturally relevant teaching — academic success, cultural competence and sociopolitical consciousness — which are more relevant than ever as educators and advocates decry declining civics education and persistent achievement gaps. It means giving students space to talk about an event like the killing of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri, and letting students choose to investigate problems that affect them rather than teachers setting their own social justice agendas in the classroom.

Based at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Ladson-Billings was elected president of the National Academy of Education in 2016 and has earned numerous awards for her research on teaching and the intersection of education and Critical Race Theory.

Ladson-Billings talked to The 74 about how her work is misinterpreted, the role of educators in Trump’s America and why she prefers the phrase “education debt” to “achievement gap.”

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: After all these years, how do you define culturally relevant teaching?

Ladson-Billings: I’ve never changed it. What’s changed is the way people have interpreted it. But I defined it as a threefold approach to ensuring that all children are successful. That approach requires a focus on students’ learning, an attempt to develop their cultural competence, and to increase their sociopolitical or critical consciousness. And for me, that’s an all-or-nothing proposition — you can’t do one or two and say, “Oh, I’m being culturally relevant.” You’ve got to do all three things.

How do you think the interpretation of your work has changed?

I think that people don’t actually read the work. They may read one article that appeals to them and think they know what we’re talking about, and so as a result someone will celebrate an additional holiday or color in a different face on the bulletin board or use one activity that they’ve seen somewhere and then claim, “Oh, we’re being culturally relevant.” Or they’ll say, “Oh, we’re studying Benjamin Banneker in mathematics — that’s being culturally relevant.” Well, that’s doing an activity. It really has to do with a philosophical outlook towards one’s approach to teaching.

A hallmark for me of a culturally relevant teacher is someone who understands that we’re operating in a fundamentally inequitable system — they take that as a given. And that the teacher’s role is not merely to help kids fit into an unfair system, but rather to give them the skills, the knowledge and the dispositions to change the inequity. The idea is not to get more people at the top of an unfair pyramid; the idea is to say the pyramid is the wrong structure. How can we really create a circle, if you will, that includes everybody?

How would you explain the way that those three fit together?

I, of course, saw it over the three years that I spent observing these outstanding teachers [to write The Dreamkeepers, a book about successful teachers of African-American students]. When the teacher raises questions about what they’re teaching, they ask, “What’s the cultural implication of teaching this?” Then, “What do I want kids to do with it?” I often talk about that sociopolitical consciousness as answering the “why” questions. What I mean by that is, kids come to us all the time and say, “Why do we have to study this? Why do we have to learn this?” A typical teacher response is something like “You’re going to need this next year.” That’s not an answer.

Culturally relevant teachers say “OK, here’s why you need to know this: because if we’re going to change this, if we’re going to actually speak to this level of unfairness and inequity, then you need some tools. You need to be able to read and you need to be able to write, so that you can speak directly to this.” I think the other thing that happens is teachers pick up their own causes and decide, “Oh, I’m making my kids critically conscious.” You’re getting kids to do the work that you’re interested in. Sometimes critical consciousness moves away from what kids really care about.

I find that teachers often shy away from critical consciousness because they’re afraid that it’s too political. A perfect example for me is some years ago when Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, that district in Ferguson sent out a directive that teachers not talk about this. This is exactly what kids are talking about every single day, because at night when they go home and turn on the news, their streets are flooded with protesters, and they need an adult to help make sense of this. But the school has said, “No, you can’t talk about this.”

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about your work?

That it’s for black children. What I tried to do is figure out, if black children are the poorest performers, what could we do to improve their performance that would likely improve performance for everybody? One of the things I did is, rather than make them the object, I made them the subject of the study. I centered their experience.

Most research centers the experience of white, middle-class students. If they don’t tell you the race or ethnicity of the kids, it’s because typically those are white, middle-class kids. You’re supposed to know that. They need to be called just kids. And I decided I would do a study and black students would be just kids. But because they happened to be black, people presume that this work is only for black students.

Are there any other misconceptions you worry about?

Probably that people think that it’s something that can be packaged. Someone will come along with something like culturally responsive lessons, as if teachers don’t have to think and plan and decide what appropriate lessons are for the students they are teaching. That’s going to be different for different teachers. If your classroom has a number of recent immigrant students, then the package is not going to attend to that. The way teacher education is set up is that people believe, “Oh, you can always just buy something that will attend to whatever the issue is,” and it really does require thoughtfulness and planning.

In the past few years, we’ve seen some cities and schools adding things like African-American history class or Mexican-American studies. In Texas, for example, there was a years-long fight over whether a Mexican-American studies course should be allowed, and then another fight about what it should be called. How do issues like that that fit into what you advocate for?

The ethnic studies debate goes back 50 years — it’s not a new one — but what research has found is just changing the content is never going to be enough, if you are pedagogically doing the very same things: Read the chapter, answer the questions at the back of the book, come take the test. You really haven’t attended to the deep cultural concerns. What happens is school districts want you to do just that — teach exactly the way you’ve been teaching, just change the information. That does little or nothing to increase engagement, and it certainly doesn’t help kids feel any more empowered about what they’re learning.

Beyond ethnic studies courses, what are other steps that can be taken districtwide to make teaching more culturally relevant?

We probably need to have a serious revamping of the curriculum. I do think there’s a place for ethnic studies courses; I have taught those courses. It’s not either/or. It’s always a both/and. You still have to go back to a course like U.S. history and ask, fundamentally, “What’s missing?”

The fear of just having ethnic studies classes is you create a kind of ethnic balkanization, and people think that the ethnic pride students might exhibit turns into hatred, and that’s really never been the point. But it will come across that way if you haven’t been thoughtful about curriculum development.

Here’s what I mean: If you take an ethnic studies course and one week we’re focusing on Mexican Americans and then one week we’re focusing on American Indians, what you get is that people are engaged and less engaged depending on what group you’re in. A very different approach would be to look across the common experiences of people and pull all those experiences to illustrate a point or an issue. If I were teaching one of these courses, one of the first issues I might take up with students is migration, because everybody has a migration story, not just Mexican-Americans or Central Americans. Everybody’s got one. It’s a fundamental question: How did you get here? That can be answered by everybody, and we can look across the migration stories to raise other kinds of questions. You might have a study about a concept like assimilation and acculturation: What is it that your family has done to assimilate into American society, or how have they acculturated if they haven’t assimilated? How have they made life here work for them?

Taking big ideas and then pulling across all of the different cultural groups requires a lot of knowledge, though, and a lot of times we get lazy. It’s much easier to say, “Oh, I’m doing this two weeks on the Irish Americans.” Now, the Irish Americans have a very interesting migration story. If you’ve ever seen the film Gangs of New York, you’re kind of shocked: “Oh my gosh, they went through all of this. I just assumed they were white and they just fit in.” No, they didn’t. There’s a powerful migration story in the same way that the Chinese on the West Coast have a powerful migration story.

You said in an interview with Madison 365 that you had a lot of African-American teachers when you were growing up in Philadelphia. How do you think that affected you and how you perceived education?

It probably impacted me because my teachers didn’t have to censor themselves. Here’s an example: If our teachers were taking us on a field trip — say, downtown, a more public space where you’re going to come across a majority of people who back then would have been white — our teachers didn’t have any trouble saying, “Listen, you have to behave a particular way because when we get there, people are going to look at you, because they probably haven’t seen little black children. If you do anything, if you misbehave in any way, they’re not just gonna say, “Oh, look at those badly behaved children.” They’re gonna say, “Look at those badly behaved black children.”

OK, we got that. In an integrated setting, our teachers wouldn’t have been able to say that. Our white teachers would never say that to us. So there were ways in which black teachers could close the door and be real with us. I’m sure you’ve seen the Procter & Gamble advertisement about “the talk.” There was some backlash because people don’t realize, our parents really do give us this talk. And as a parent I have given my children that talk. That’s what black teachers are able to do: give us a talk.

New York City’s schools chancellor, Richard Carranza, said in 2018 he was going to prioritize implicit bias training for all educators in the district. Do you see that as a step in the right direction, and to what extent do you think something like that could have an impact?

So, here’s where I maybe differ from a lot of people who do this work. I look carefully at Jennifer Eberhardt’s work. She’s a psychologist at Stanford who was credited with discovering what actually happens in the brain around implicit bias. I believe there is something called implicit bias. What concerns me is that it becomes the default, and what I mean by that is: People do things that they have no business doing, and the response is “Well, you know, I have implicit bias.” Duh! So I’m worried that it becomes an excuse …

When we do this work, there are certain baselines that people have to have. Number one, they have to believe that racism is real, and number two, they have to believe that they may be acting on it. Now, we have some people [who] don’t want to participate just because of that. For example, I was in Green Bay and teachers wanted to know some resources for implicit bias training, and I said, “I don’t think that’s the first place you go.” You’re already setting people up to be defensive. You’re telling them walking in the room, “You’re biased.” It’s true for all of us, but not everybody can hear that. And if they can’t hear it, it’s difficult to work with them.

So I know what they’re trying to do, but the question is, is it exacerbating the problem, where people begin to think, “Well, there’s nothing I can do about it; it’s just the way my brain is working?” Or is it actually educating them to the point where their behavior changes?

Is there something that would be a better strategy for Carranza and other superintendents to deal with implicit bias among teachers?

First of all, I think that almost all of this work has to be local. I think we have to stop bringing 1,500 people in the room and thinking we can preach them into better behavior. I just don’t think that’s going to work. But I know we work on economies of scale, so we just think, “Let’s bring a trainer in and just train everybody.”

You have to be able to look at your specific and local context, so for these teachers in Green Bay, I told them, “Well, why don’t you guys do this? Why don’t you go back and just pull your data, look at your suspension rates and who’s being suspended, look who’s being assigned to special education, look who gets into advanced placement class, look who’s in honors — just document that, and then share that with each other and say, ‘How do we explain it?’”

People’s explanations will help you understand why certain things are happening. If their explanation is, “Well, you know, we have all these poor kids,” OK, the poverty is not gonna stop next week. Are we saying because the children are poor, they are incapable of X, Y or Z?

You said several years ago that what we typically call the achievement gap is really more like an education debt. What do you mean by that?

When we use that gap language, we are often putting the blame on the individual child or their family or, in some cases, the teacher. It suggests that everybody else is doing just great and you guys need to catch up. I’m saying it’s much more complex than that.

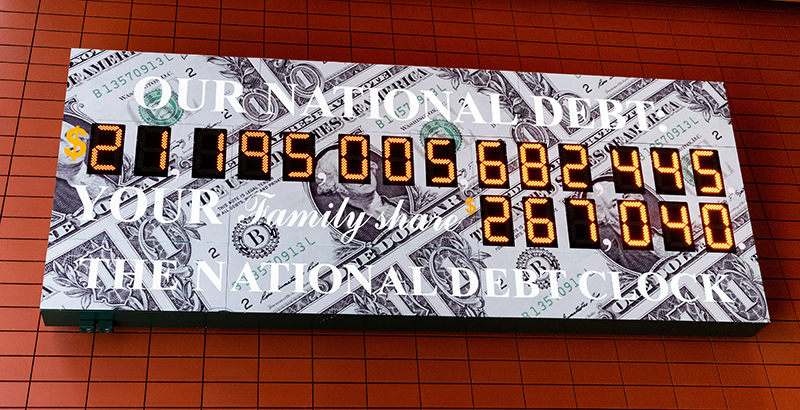

And I came across the notion of the debt when I was headed home from New York and was stuck in traffic, as is true of everybody headed home from New York. I looked up and saw a billboard, and it was lit up and it had numbers, and it was spinning like crazy. And I happened to read the caption under this huge number that said, “This is the national debt.” And then, under that big huge number was another number that was pretty big, and it was spinning too, and that caption read, “And this is your portion of it.”

I thought, “Oh my God, there’s no way I can pay this.” For me, the question was, “Why did I think I needed to pay that? Why did I feel like, ‘Oh, I have this responsibility?’” Well, part of it is that the rhetoric of this country has been “We’ve got to do something about the national debt. We can’t keep leaving our kids this debt.” Every politician will get up in front of people and say, “We’ve gotta reduce the debt.” Now, the way that’s framed, it’s everybody’s responsibility. It’s not just the congressperson’s responsibility, it’s not just the president’s responsibility, it’s not just the governor’s responsibility. It’s everybody’s responsibility, and we are all saying, “We don’t like this debt, this is hurting the country, we can’t leave our kids in this sad situation with all this debt.”

I thought, “Well, yeah, but we’ve left them what I would call an education debt.” There are things that we didn’t just start doing — we’ve been doing them for a very, very long time. We have historically not provided a good education for all of our kids. Black children didn’t even get universal secondary education until the 1960s — not the 1860s, the 1960s. So there were still places in this country where you couldn’t go to high school if you were black.

We’ve never done well by American Indians in terms of their education, and on and on, so we have this historical legacy. We’ve also had the funding legacy. We have done inequitable funding for centuries. There’s some school districts that just haven’t gotten adequate resources. We continue to do that. There’s a huge difference between the way urban and suburban schools are funded. Then we’ve also had this political debt, where if you didn’t start letting people vote until 1965, then they haven’t had a history or a legacy of voting and participating. They couldn’t even pick their school board members in some places. They couldn’t pick their own mayors and city council folks and governors.

So all of this is accumulated, and that’s what I mean by debt. To me, that’s not a gap, that is really a debt, and society owes large groups of people because for generations, we haven’t done right by them and their families.

You originally wrote that more than 12 years ago. Do you think since that time the country has made any progress on that debt?

Not much. Because, number one, we haven’t acknowledged that it exists. We’re still talking about achievement gaps.

There have been a lot of headlines and talk lately about teacher diversity and the teacher pipeline, which is leaving us with about 80 percent white teachers, and more broadly, people are re-examining the importance of representation for kids. What do you think would help attract more minority teachers to the field and fix some of the leaks in the teacher pipeline?

The unspoken thing about that is you can’t be a teacher if you don’t graduate from high school. That’s a fundamental truth. If you’re not improving the rate at which kids of color are leaving high school, that’s not a leak, that’s a break in the pipeline. You’ve already decided, you’re not going anywhere. That’s a huge problem.

The second issue is, people have other choices, so how would you convince someone to take a low-status, low-paying job when they could have an opportunity now to go into a profession that will remunerate them more highly?

The third issue is that we keep talking about this mismatch between students and teachers as if it’s only about kids of color and their teachers. White children desperately need people of color as teachers. I keep getting students at the college level who tell me, “You’re the first black teacher I ever had.” That’s a problem. That’s a real problem because do you think you can go out into the world and interact with people when you’ve never had an ongoing relationship with someone who’s different from you? There is some data that suggests that white children benefit from having teachers of color. We rarely talk about that. We think, well, we just can fix everything that is going on with black or brown children if they have black or brown teachers.

You were quoted in 2017 in Education Week about the importance of kids having access to at least one culture besides their own. We know that our schools remain racially segregated even though the student body is more diverse than ever. Do you think integration is part of improving achievement for kids of color?

Yeah, integration but not desegregation. They’re two different things. Desegregation is often about just trying to get the numbers right, and that’s essentially what Brown v. Board of Education required, that you don’t have just a concentration of kids of one race or ethnicity. But one thing we don’t talk about: The most segregated group of kids in the country are white kids. We never refer to their schools as segregated. We refer to black and brown kids as going to segregated schools.

So, integration in which kids of different races and ethnicities have an opportunity to fully participate in the life of the school is what I would hope to see. What I see with schools’ desegregation models is that kids get bused somewhere, they’re in school for the school hours, but they can’t — because of scheduling and transportation resources — really participate in the school, so they can’t stay after school. For example, I remember when we lived in California, one of my kids’ Little League coaches had a son who was an excellent baseball player, and he loved the game just like his dad loved the game. But he was bused across town, and he could not stay after school for practice because there was no bus to bring him back, and his parents both worked so they couldn’t take off to pick this kid up from practice, and so he couldn’t stay. So here, he’s gone to a school to desegregate it, but it’s not integrated. He’s not participating in the entire life of the school. So I want to make that distinction between integration and desegregation because I think integration affords kids something totally different than school desegregation.

Integration has become such a political word, especially in light of the recent controversies about integrating schools in New York City and making the specialized schools more diverse. Do you have a theory about how schools could be integrated fairly and effectively in a way that benefits students?

The challenge is really further upstream. It’s sort of like the pipeline issue. We’re asking about people at the college level when the truth of the matter is, the problem is at the high school when the people don’t graduate. When it comes to school integration, the problem is not at the school, the problem is in the neighborhood, and neighborhoods are deeply, deeply segregated. And you can’t make people live together. You just can’t. So you end up having schools try to engineer a fix that never makes anybody happy and is almost always on the backs of kids in the minority, so it’s always the black and brown kids getting on the bus headed all the way across town. When you tell white people that they need to do that, they opt out of the public system.

The only instance where you see white folks make this extra effort to get their kids somewhere is when that school is considered a specialty school, so in Philadelphia, it would be Central High School, where you have 90-plus-percent college-going rate; in Chicago it would be Whitney Young; in San Francisco, it’s Lowell; in New York, it’s Bronx Science. I mean, it’s not that white people won’t go to certain neighborhoods — they’ll go if it’s what they believe is the absolute best quality.

I noticed you’ve written about the problem of white people calling the police on black people for no reason, saying that it stems from racism, not ignorance, and it comes from white people having a sense of entitlement about where people should and shouldn’t be. Certainly in a culturally relevant classroom, teachers talk to their students about these kinds of incidents. What do teachers need to know to be able to have those conversations at school?

I think the first thing to ask, is, “What are your kids’ experiences? Have they themselves experienced something like this?” I remember I used to have this thing about making sure I was in the mall the day after Christmas … and I remember being there one day and I saw these three little black boys somewhere between the ages of 13 and 14, being not black boys, but being 13- and 14-year-old boys, being silly, being loud, true of every 13- or 14-year-old group of boys I’ve ever known, regardless of race or ethnicity. Everywhere they went in the store, white people would move away from them. At one point, it was so obvious that I went up and said to them, “Hey, you guys got a disease or something?” They started laughing and they said, “Yeah, we must have it, we must have something.” They recognized that people were going out of their way to avoid them.

You have to know what the kids’ experiences are. Has something ever happened to you that you believe happened because of your race or your ethnicity or your age … because kids will think of all kinds of reasons. “Oh, they thought we were poor, they thought we were loud.” Students don’t always run to “because we were black” as an explanation. Sometimes that’s in our head, but we have to know what the kids’ experiences are to be able to have these conversations.

Is there any other advice or guidance that you would give to a teacher who wanted to talk about something like this but wasn’t sure how?

I would say, rather than force it, allow it to come to them. You have to have a space in the classroom where kids feel free to say, “Hey, did y’all see this thing on the news,” rather than have the teacher say “There’s racism in the society …” Sometimes the kids are just not there. And again it gets back to, we’re not there for our agenda. We should be there to … let students know that whatever is of concern to them, they ought to feel free to bring it here because we’re going to talk about it, we’re going to try to make sense of it.

You’ve also written that the president’s series of comment about athlete protests “hits at the very heart of racist sentiments in this country,” and you have been pretty candid about your general feelings about Trump. What do you see as the role of teachers in this moment of so much division and conflict in the U.S.?

Again, it is to provide the space for kids to have the conversations and to help them provide the evidence. I know that our emotions and feelings are running high, but part of the skills that we as educators should be giving kids are analytical skills in which you don’t just say, “Because I feel this way” — but you are able to say, “And here is the evidence.”

My point about his issue with the athletes was, you don’t lose your citizen’s rights because you decide to be an athlete. You still get to be a citizen. There is a very long tradition of protests by high-profile people in this society. The back of apartheid is broken not just because of the work of the ordinary people, but because people like Stevie Wonder and Harry Belafonte, even Aretha Franklin, said something about it. Stevie Wonder went to jail protesting apartheid. And because you are so highly visible, you’re going to get the attention.

In 2016, you were named the president of the National Academy of Education. What would you like to achieve in that role?

The academy is a relatively small group of people. There’s somewhere in the 200s maybe, and it’s honorific … We have been elected to be in the academy, but we do have some ability to help push an education research agenda, which is different from, say, a political agenda. We have indeed put out some statements about some things that have happened since I’ve been president, from the perspective of “How does this impact education research?”

The first statement we put out was about the decision to ask the citizenship question on the census. Essentially, from our place as researchers, it is likely to skew the data because people won’t answer, and so if we don’t have good data, we can’t make good decisions. So we didn’t really put it in a political context as much as a research context and said, “If you do this, this is the likely outcome, and this is why this is detrimental to the work we’re trying to do.”

Then we also put out a statement in conjunction with some others academies — the National Academy of Science, National Academy of Medicine, National Academy of Engineering — to say that the separation of children at the border has a long-term psycho-social impact, and so just taking a kid away is not just what happened in that day, and we have pretty good research about childhood trauma and parental separation, and so you’re making a mistake to do this. That’s one of the places where the Academy has been able to speak to some current issues. But I think our long-term goal is always to improve the quality of education research.

Is there a certain teacher or a moment you remember that made you want to devote your life to the cause of education?

I didn’t want to be a teacher. I didn’t choose teaching. Teaching chose me. But I did have a teacher who made a profound impact on me, and I talked about her in a variety of places. That was my fifth-grade teacher, Ethel Benn. She was just someone who, first of all, had such deep pride in being black, which, in the era when I was in school, was strange. Nobody wanted to be black, but Miss Benn would tell us wonderful stories, which I know were not part of the curriculum, about the accomplishments of black people.

The first time I ever heard about W.E.B. DuBois was in fifth grade from Miss Benn, and I thought she was making it up. He was one of the first people to graduate from Harvard, and I was like, “Ain’t no black people been to Harvard.” It just seemed incomprehensible. But she was also someone who was set on exposing us to a big world. Miss Benn was the school’s chorus teacher, and people wondered how we had such a big chorus at our school. Well, we had a big chorus because if you were in her class, you were in the chorus. She didn’t care if you could carry a note in a bucket of water — you were in the chorus. And being in the chorus was not merely singing, but the opportunities that she provided to take us all around the city, because we sang everywhere. That was just the coolest thing, to be able to go to parts of the city that we normally would not have gone to, because we had a teacher who thought it was important that we see more than our own neighborhood and our own backyard.

I learned to sing the Latin song “Dona Nobis Pacem” from Miss Ethel Benn in fifth grade in West Philadelphia. Now, I’m not white, I’m not Catholic, I’m not any of the things that I associate with that song, but I learned that song, and interestingly enough, by the time I got to where I had to take a foreign language, the language I decided to take was Latin. So yeah, she was crucial, and she was generous … The funny thing about me and Miss Benn is I did not want to be in her classroom. She just seemed so old, old-fashioned. Now, she was probably younger than I am right now. She just seemed like an old lady. I remember when I found out I was assigned to her, I begged my parents to get me out of there. I wanted to be in this younger, white woman’s classroom across the hall. Because she was cute, and she had a ponytail, and she wore high heels, and I said, “I want to be over there.” And my mother said, “You haven’t even given her a chance. You decided from day one you don’t want to be there. No, we’re not changing anything.”

And that was good, because Miss Benn made a huge impression on me.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)