The State of America’s Student-Teacher Racial Gap: Our Public School System Has Been Majority-Minority for Years, but 80 Percent of Teachers Are Still White

In 2014, according to U.S. Department of Education projections, the demographics of the nation’s classrooms were set to break a historic barrier: For the first time, the majority of students in America’s public schools would no longer be white.

Based on population trends, National Center for Education Statistics predicted that 50.3 percent of the student body for the 2014-15 school year would be people of color — a precursor to the country as a whole becoming majority-minority in the next three decades. (The Office for Civil Rights is expected to release more complete student demographic information for that time span in the next year.)

But are the classrooms of 2018 and beyond rising to meet this seismic shift?

Many critics are less than optimistic. “In general, U.S. schools tend to change more slowly than the country around them, for better or worse,” Jon Valant, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, told The 74 in an email. “I’m not sure that I’m seeing or expecting a major direct response to the projected demographic shifts.”

Although America is becoming more diverse each year, and is expected to have a majority-minority population by 2044, the teaching force is not keeping up with the changing racial makeup of America’s children. Elementary and secondary school teachers form a group far whiter and more female than the students in their classrooms, despite a strong body of research that indicates that a diverse teaching staff benefits students of all races.

Moreover, gaps in academic achievement and high school graduation rates mean large numbers of minority students are falling behind every year, leaving them unprepared to enter the workforce, succeed in college, and participate in American civic life.

The demographic shift is partially linked to a decline in the white population, which dropped from 58.45 percent of students in 2003-04 to an estimated 50.4 percent a decade later. During the same period, the percentage of blacks dropped slightly, from 16.88 percent to roughly 15.5 percent, while the Asian population saw a small increase, from 4.53 percent to an estimated 5.2 percent.

But the shift is largely driven by exponential growth in the Hispanic population, which is younger and has a higher fertility rate than that of whites. Latino students made up 24.8 percent in 2013-14, up from 18.94 percent in 2003-04. During that span, every state saw its share of Hispanic students increase. Over the same period, every state except Mississippi and Washington, D.C., saw its share of white students decline.

In recent years, the Hispanic growth rate has slowed and even been surpassed by that of the Asian population. Nonetheless, Hispanics accounted for 51 percent of overall U.S. population growth from 2016 to 2017, according to the Pew Research Center.

The shift is comprehensive. Most communities are seeing increased diversity, even small towns and rural regions, according to a 2015 report by the Urban Institute. Although Florida and states in the Southwest have seen the most dramatic influx of Hispanic students, school districts across the nation are becoming less white and can expect more diversity each year, at least for the next few decades. For example, over the past five years, the number of districts in Minnesota with majority-minority enrollment has doubled, with almost a quarter of all public school students there attending classes in such districts, MinnPost reported.

“Pretty much the entire United States is becoming at least a little less white,” Steven Martin, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, said in the report. “Not only are white shares decreasing nationwide, but they are decreasing everywhere — in the Midwest and the Southeast, in big cities and in rural areas, in places where whites are leaving and in places where whites are moving to.”

A towering teacher diversity gap

The growth in the population of minority students is occurring as the demographics of the teaching profession have remained largely static — mostly white and female.

The potential harm of this mismatch is underscored by research showing that African-American students benefit from having even one teacher who looks like them in elementary school. For instance, a study of a group of black North Carolina students in the early 2000s found that having just one black teacher in grade 3, 4, or 5 decreased the dropout rate by nearly a third and also made students more likely to say they planned to go to college. The benefits were even stronger for boys and students living in poverty, and there were no negative effects for students of other races. Furthermore, research indicates that black students are less likely to face exclusionary discipline — suspensions and expulsions that remove them from the classroom — when taught by same-race teachers. (The effects of same-race teachers for Hispanic students have not been studied enough to know whether there is an added benefit.)

Less than 20 percent of teachers are minorities nationwide, compared with more than half of students. In fact, the teacher diversity gap is “larger than expected based on racial differences in bachelor’s degree attainment alone,” according to a 2017 Brookings Institution report on teacher diversity and educational attainment.

For example, Hispanic students make up about one-quarter of all K-12 students — but less than 10 percent of all teachers, according to data compiled by the Urban Institute last year. Although Hispanic college graduates are becoming teachers at nearly the same rate as white graduates, the numbers have not kept pace with explosive growth in the numbers of Hispanic children. Additionally, Hispanics lag behind other groups in high school and college graduation rates, which shrinks the pool of potential teachers, as The 74 has reported.

The reasons for the gap are many: hiring bias, certification tests that teachers of color are less likely to pass, a racial gap in bachelor’s degree attainment, and lower retention rates for teachers of color, among other factors. Moreover, new research based on teacher turnover in North Carolina suggests that black teachers may choose to teach in more challenging school settings, where turnover rates are higher for all educators, which could further exacerbate the overall retention gap.

Making things worse, when teachers from underrepresented groups work at schools where most teachers are white, they are often tasked with additional informal roles, such as translating for Spanish-speaking parents. Having a teacher who can fill those cultural roles benefits students but can also be exhausting for teachers, potentially causing burnout, research indicates.

Urban Institute researcher Constance Lindsay, who focuses on teacher diversity, said the best way to increase teacher diversity is “getting more kids of color into college.”

“If there’s no supply, you just won’t have the diverse teachers that you need” to create school staffs that represent the students they serve, she said. This strategy for increasing diversity in the profession can prove doubly challenging, however, when exposure to same-race teachers is a proven lever for decreasing dropout rates and improving student achievement.

At the heart of the teacher diversity question is the “larger issue of education policy, which is ‘How are we going to close these achievement gaps?’” Lindsay said. In other words, the teaching profession can’t get more diverse without more students of color entering and graduating from college, an outcome that hinges in part on better schools and teachers to get them there.

Organizations including KIPP charter schools and Teach for America have prioritized hiring teachers who look like their students, as have some individual districts, spurred by the research and increasing awareness about the importance of teacher diversity. Yet Lindsay and others say the change isn’t coming fast enough.

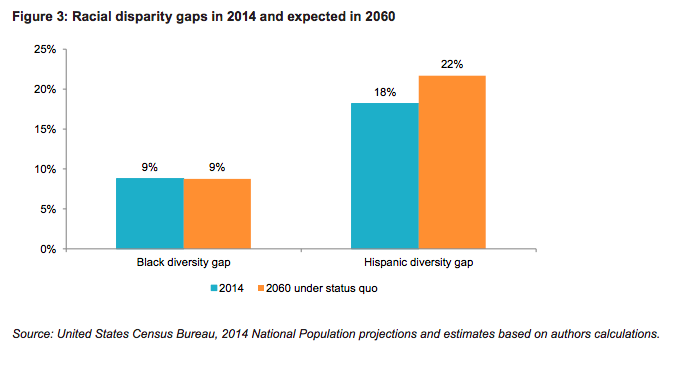

By 2030, people of color will make up more than half the total workforce, but projections by Brookings and the National Council on Teacher Quality indicate that the teaching force will not keep pace and the diversity gap will remain unless major changes occur.

Another part of the problem is that teaching is not the only profession where leaders are actively looking to attract college-educated minorities.

As other industries seek to diversify their workforces, college graduates of color may be recruited to jobs with more prestige or higher pay, said Lisette Partelow, director of K-12 strategic initiatives at the Center for American Progress. Additionally, she said, teaching, known for poor working conditions and low pay, has a “reputation problem,” which can deter or push out teachers with heavy student loan burdens or other financial obligations.

In addition to empowering more minority students to graduate from college, Partelow pointed to initiatives like Boston’s teacher residency program, which recruits local college graduates to work as educators, and has a track record of attracting more people of color than traditional teacher preparation programs. Additionally, paying teachers better and treating them like their peers in other professions would help attract more graduates to teaching and keep them in the classroom, she said.

Some critics argue that efforts to make the profession more diverse, such as changing certification exams or creating alternative routes to the classroom, will lead to lower standards.

Data indicate that white candidates are more likely to pass the Praxis tests used for certification in many states than their black and Hispanic counterparts. A report by Educational Testing Service, which administers Praxis, argues that test score gaps between white and black teacher candidates are partially due to a college readiness and achievement gap and broader societal inequities between the races. The racial gap was wider for students who earned higher grades in college, possibly “a function of the economic status and standing of individual test-takers, which may also play a part in their preparation for higher education and the selectivity of the colleges and universities they attend,” according to the report.

Moreover, at least one study offers a possible counterexample to the value of a diverse teaching force: A long-delayed, court-ordered Louisiana program to hire more black teachers was found to have no measurable effect on student achievement when implemented in 2010.

Racial gaps in the classroom could exacerbate achievement gaps between schools

As America becomes increasingly non-white, a stubborn racial diversity gap between students and educators also has the potential to exacerbate existing racial gaps in student achievement and discipline.

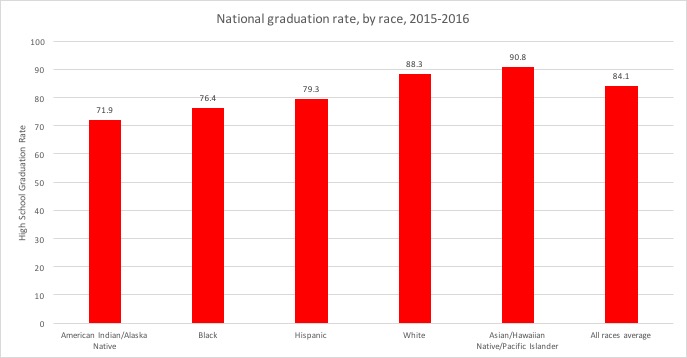

Although the high school graduation rate hit a five-year high in 2016, racial gaps remain, with Asian students graduating at the highest rate, followed by white students, and other minority groups lagging.

(Data source: National Center for Education Statistics)

The gaps in graduation rate mirror yawning achievement gaps, which have plagued American education for decades.

“For as long as we’ve been measuring test score gaps in this country, the gaps have been very, very large, and that is still the case today,” Brookings’ Valant told The 74 in an interview.

Valant said the gaps translate into large groups of students left unprepared for life after high school.

“Very large gaps, coupled with a very large population of students of color and students from poor families, means that we have these large populations of students who are entering college and career at a large disadvantage,” Valant said.

The gaps could grow worse as the population of minority students is projected to increase even more over the next ten years, ahead of the general population and far faster than the teaching force. In 2025, NCES projects the student population will be 45.6 percent white, 15.2 percent black, 28.5 percent Hispanic, 6.1 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.9 percent American Indian/Alaska Native, and 3.6 percent two or more races.

Experts told The 74 they were glad issues like teacher diversity have been getting attention from advocates and policymakers lately, but they agreed there is a long way to go before schools are prepared to serve all children. While educator diversity is one lever for improving outcomes, increasing the number of minority teachers alone is not enough.

Rather than fixating on one lever for improving education for minority students, Valant said, “it’s much more likely that we have to get a lot of different things right at the same time.”

Related

● Study: Gaps in Civics Performance Between Black and White Students Deepened in NCLB Era

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)