Regifted: The First 7 Questions to Ask About Mayor de Blasio’s Ambitious Plan to Integrate New York City’s Specialized High Schools

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s ambitious plan to fully integrate New York City’s elite specialized high schools may turn out to be a milestone of social justice and educational equality, but overthrowing the current regime won’t be easy.

At a Sunday press conference, the mayor said “the stars have aligned” behind his proposal to discontinue using the test that by law has been the sole criterion for admission to the schools, which include the prestigious Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Tech, for nearly a half-century. He would replace it with grades, state test scores, and other measures, and then select the top performers from every middle school.

But alumni groups hit back on Monday, blasting the mayor’s effort to quickly push a bill through the Assembly without public comment, while organizations representing Chinese immigrants — whose children make up a significant proportion of the student population at the specialized schools — called the proposal “racist” and promised to fight against it.

Following the bold proposal and the emotional backlash, seven key questions about the path forward for the top high schools in America’s largest school district:

1 Why now?

It’s easy to see why the mayor is confident in his timing; cultural winds are gathered at his back. School desegregation has emerged as a central concern, and he has bet that its proponents, while unhappy with what they saw as a tepid plan to diversify city schools last year, will energize around the new cause.

The use of standardized exams as a measure of academic ability has lost luster as well. Heavy testing loads in state accountability systems were challenged in New York and elsewhere. The list of colleges that no longer require the SAT or ACT continues to grow (most top-tier schools still require them). Research shows that even a good test provides a limited picture of a student’s gifts and potential.

In an analysis I wrote last month of New York City enrollment data, I also found that the tests helped push the city’s top boys and girls to sort themselves into different types of schools.

De Blasio’s new schools chancellor, Richard Carranza, has proved an ardent spokesman, coming out of the gate ahead of the mayor by scolding white parents who resisted integration in their neighborhood schools and criticizing not just specialized high school admissions but also screened schools, which enroll students based on grades, state scores, and the like — criteria similar to de Blasio’s prescription for the specialized schools.

2 Does the mayor need state approval for his plan?

No — and yes.

The plan has two parts. The first is an expansion of the Discovery program, which gives a second try to low-income students who came close to passing the specialized test the first time. The mayor can do this unilaterally (and has in the past).

But the second and more important part depends on state legislators overturning or amending a 1971 law that established test-only admissions. It’s a big assumption, but if that were to happen, the city would then gradually phase out the test over three years while moving to admissions based on identifying the top performers in each middle school.

In part one, the city would expand Discovery so that it produces 20 percent of specialized offers, up from 5 percent this year. Given past admissions trends, that’s about 1,000 seats.

There are a few problems. First, past efforts to expand Discovery haven’t worked. Chalkbeat reported that the program tripled in size under de Blasio, but 78 percent of students offered admission under its auspices in 2017 were white or Asian (the city noted that a higher percentage of black and Hispanic students were admitted under Discovery than through regular admissions).

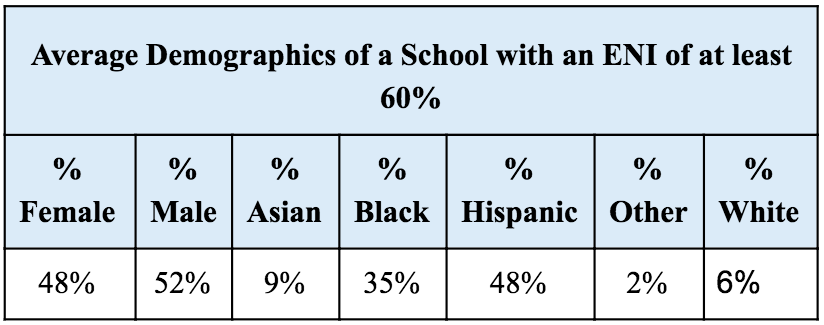

The new plan offers what it suggests is a fix: Only students in high-poverty middle schools will be eligible. The mix will be quite different: About 83 percent of students in these schools are black or Hispanic, according to the Department of Education, and 15 percent are white or Asian.

It’s worth noting that, as of 2017, 23.4 percent of Asian Americans in New York City live in poverty, according to city data. They are among the stoutest defenders of a system that has provided a piece of the American dream: an amazing 28.1 percent of specialized school offers between 2005 and 2013 went to students speaking Chinese at home, according to an NYU study. That figure would decrease substantially under the de Blasio plan.

In all, Asian-American students make up 61 percent of the specialized high school enrollment, though they are just 16 percent of city students. White students account for about one-quarter of specialized school students and are 15 percent of city students overall.

3 Can the mayor secure support from state legislators?

Maybe — but not right away. The Assembly will consider an amendment this Wednesday to replace the test, but even with backing by the entire chamber, there’s no way forward until after November.

His failed effort to help Democrats win the state Senate in 2014 has left de Blasio persona non grata in the upper house, where Republicans force him each year to endure a late-into-the-night negotiation that ends each time in a one-year renewal of his control over schools. (By contrast, Mayor Michael Bloomberg received a six-year renewal.)

Should Democrats win the chamber outright in the fall (which is not at all clear), it’s conceivable that a combination of the zeitgeist and electoral interests could bring about at least a partial change to the law.

While unlikely, it might help if the mayor were able to bring around dissenting Democratic senators who represent districts that are home to large numbers of specialized school students.

In April, Democratic senators Jamaal Bailey, whose district adjoins two Bronx specialized schools, and Toby Stavisky, whose Queens district includes a sizable Asian student population, announced legislation to expand Discovery and early screening for gifted students, and create a practice specialized test, akin to the PSAT, for all sixth-graders.

Neither contemplated changes to admissions policy, and Stavisky has publicly opposed the new proposal. Both graduated from Bronx High School of Science.

Similarly, while de Blasio can count on strong support from City Council, Education Committee chairman Mark Treyger has not endorsed the plan, perhaps because his south Brooklyn district includes a high-achieving Russian population. (Treyger’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

The elephant in the room in all-important state policy discussions is Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Cuomo enjoys making life difficult for de Blasio, but with a re-election challenge on his left from actress Cynthia Nixon, he may have less leeway than usual. His initial tack has been to support the aim of integration while tossing water on de Blasio’s approach. “The mayor raises legitimate concerns,” Cuomo said Tuesday, adding, “I don’t know that there’s much of an appetite in Albany now to get into a new bill, a new issue.”

4 Does the mayor have the authority to change how the five newer specialized schools admit students?

It seems so.

The two-year expansion of Discovery wouldn’t much offset the racial imbalance in the schools: Minority enrollment would increase to 16 percent from 9 percent, according to the city. The rest would depend on the disposition of the Senate.

But lawyers say the mayor can bypass Albany to implement the admissions changes he wants in the five specialized schools — The Brooklyn Latin School; High School of Mathematics, Science and Engineering at the City College of New York; High School of American Studies at Lehman College; Queens High School for the Sciences at York, and Staten Island Technical High School — that weren’t around when the testing law was codified.

“It’s a lack of political courage not to have separated out the five nonmandated schools from his proposal,” said David Bloomfield, a professor of education law at Brooklyn College who has closely followed the issue. “It seems that there’s no question that if he can designate them as specialized, he can un-designate them.”

The schools were created by Mayor Michael Bloomberg between 2002 and 2006.

The mayor has said city lawyers are investigating whether he has the authority to make the changes, which would likely be politically unpopular, particularly in the school communities. Bloomfield said de Blasio has made up “the legal question out of whole cloth and buried it in the bowels of the corporation counsel.”

If the specialized school plan stalls, the mayor may face increasing pressure to redesignate the five schools as something other than “specialized.”

5 How will changing the student bodies at specialized schools affect other NYC schools?

No one’s quite sure.

If the mayor is able to win changes to the law, a three-year phase-out of the specialized test would culminate in admissions being offered to the top 7 percent of students, based on their academic records, in each middle school. A small percentage of seats would be saved for students in nonpublic schools who are new to the city or came close to qualifying. The model resembles the University of Texas’s “Talented Tenth” policy, an idea that has been floated among advocates for years.

The city estimates that, going forward, 45 percent of specialized offers would go to black and Hispanic students (almost as strikingly, the percentage of female students would rise from 44 percent to 62 percent).

But officials said they won’t be able to model changes at other high schools until they are able to see what the new specialized school enrollment looks like.

6 Who will oversee the plan once it starts?

Carranza and his team have overall ownership, but specialized schools typically function as closed-off cultures led by highly autonomous principals. Given what would likely be defining shifts in school culture, these leaders’ ability to manage change would go a long way in determining the plan’s success.

7 Is the proposal in the best interest of students?

Yes, and research backs it up.

Given what we know about the benefits of integration, about testing, about poverty, the status quo isn’t tolerable.

The racial, ethnic, and gender imbalances in specialized schools haven’t changed in decades. This year, five of the schools accepted 11 or fewer black students; three schools accepted five or fewer.

Of the 3,368 students enrolled last year at Stuyvesant, the city’s most decorated high school, only 106 were black or Hispanic.

In all, black and Hispanic students make up 10 percent of the enrollment in specialized schools even though they represent 70 percent of city students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)