Nearly a Year Into Remote Learning, How 3 NYC Teachers Are Digging Deep to Connect With Their Students Through a Screen

President Joe Biden is promising the resources needed to safely reopen schools this spring, and educators across the country are lining up for vaccines, but despite that progress, remote learning remains the reality for scores of teachers and students nearly a year into the pandemic.

And that’s not just the case in districts where teachers unions and administrators continue to battle over reopening plans. In New York City, the nation’s largest district and the first major urban system to offer in-person classes, some 73 percent of students have opted not to return to their schools.

New York City teachers running virtual learning have seen the array of challenges the past 11 months has inflicted upon their students, especially the 72.8 percent that are economically disadvantaged. The teachers’ tech devices have become windows into their students’ worlds during daily Zoom classes, revealing a fraction of the harm that the pandemic — and by extension, distance learning and social isolation — have caused.

In the absence of resources from a cash-strapped NYC Department of Education, which has faced criticism over whether it’s focused enough on supporting teachers trying to help kids navigate remote learning, educators have struggled to find strategies that work. Consulting the internet and leaning on each other, they’ve used creativity, trust, flexibility and a sense of fun to break through to their students.

Here, we spotlight the efforts of three educators, each working in different boroughs with students of different ages, to show how they’ve met the challenge.

Kate Gutwillig, elementary school teacher, P.S. 51, Manhattan

Special education teacher Kate Gutwillig virtually instructs about 80 fourth-grade students at P.S. 51, a high-poverty school in the heart of Times Square. All of her 9- and 10-year-old students were new to her this fall.

When we spoke with Gutwillig on Jan. 19, her school had been shuttered for the previous two weeks following a COVID outbreak. Before the closure, about half of P.S. 51’s 469 students were learning remotely full time; the other half were participating part-time in in-person learning.

For Gutwillig, a former smoker with a medical accommodation, the eeriest aspect of this year has been knowing how much of her students’ lives she’s been missing.

For Gutwillig, a former smoker with a medical accommodation, the eeriest aspect of this year has been knowing how much of her students’ lives she’s been missing.

“I’m used to seeing a lot of behavioral problems,” she said. “Now everyone’s at home. You know those problems didn’t disappear, you just don’t see [some of] them anymore.”

She cites one student as an example, a child grappling with anxiety issues, which he was receiving support for at school.

“This year, we don’t see [his apprehension,]” she said. “We know he’s probably just telling it to his mother, or he’s withholding it, but he’s not showing it to everyone like he normally would. He’s not talking to school staff the way he has in the past.”

Some of her students have vanished, only to reappear later. The school serves a number of children in temporary housing: according to Gutwillig, about one in four of her students lacks a permanent residence.

“It’s like a revolving door of new people coming in, and people disappearing,” she said. “It’s extremely sad when you form a relationship, and then [a student] just disappears. You can’t help but get attached to a child you see for three or four days. Or you see a child for the first time today, and you don’t know if you’ll see them again tomorrow.”

The teacher of 28 years has navigated these hurdles before, although this year, she said, is noticeably worse, which she attributes to the current lack of internet access among students in temporary housing.

“If they don’t have good internet, they’re set up to fail,” she said.

In an email sent in late January, DOE representatives said they’ve distributed over 12,000 iPads to students living in shelters, and that students living in shelters who report connectivity problems are supposed to receive responses within 24 hours. They declined to say how many homeless students currently lack Wi-Fi. As of November, the DOE was reporting that 60,000 NYC students were without online devices.

In an attempt to alleviate some of the suffering of the moment, Gutwillig is intentional about bringing joy into her virtual space.

“I try to spend as much time as possible making the kids laugh,” she said.

She invites her students to join her in movement-based learning games, like an exercise she’s invented to teach them about homonyms.

Gutwillig will take a group of words that sound the same but are spelled differently — like to, two and too — and assign them gestures. “To” translates to reaching for the sky, “two” becomes stretching out your arms in front of you like a zombie, and “too” is touching the floor. She says a sentence to the kids like, “I went to the store,” and the fourth-graders respond accordingly. Later, students take turns leading the group through their own homonym-filled statements.

She also has her students take “brain breaks,” when they retrieve items that fit a certain theme, like an object starting with the letter “w.”

On Inauguration Day, Gutwillig encouraged students to wear their favorite outfits, and the group played bingo on boards bearing 25 words Biden might use in his speech.

“I think of myself as a co-conspirator with the kids,” Gutwillig explained.

Lately, she’s been trying to turn emotionally fraught moments into ways for her students to take action. After the attack on the Capitol, she helped them write letters to former President Donald Trump, “telling him he was the worst president ever.”

Similarly, after the class learned that the nation faced a coin shortage over the summer, Gutwillig organized a fundraising drive. Her students gathered $400 in loose change, which they’re going to donate to a nonprofit of their choice.

Gutwillig said she’d like to see NYC Schools offering more resources to teachers trying to connect with students during the pandemic, an endeavor which, she pointed out, can be isolating.

DOE representatives said in an email that the department has a three-pronged strategy to improve remote learning: technological help, curriculum/instructional content, and training/professional development. That last piece has included offering 211 professional development sessions to 12,613 educators and administrators, they added. For context, there are some 75,000 teachers in the system.

Despite those efforts, some educators interviewed by The 74 have reported they’ve found institutional support lacking. Gutwillig said that, while she’s found the online resources made available by the DOE as part of its Passport to Social Studies curriculum helpful, “The city has provided us with little in the way of resources to teach remotely.” She said she would have liked weekly professional development on remote learning platform usage and engagement strategies.

“We should be thinking about what we’ve learned this whole time, what practices we’re going to take back with us to school in September, and how our teaching is going to change,” she said, adding that she hopes to incorporate some of the technology she’s picked up this year into her teaching in the fall.

“Now we have these other options, tools in our toolkit,” she said.

Michael Simmon, middle school teacher, IN-Tech Academy, the Bronx

Eighth-grade U.S. history teacher Michael Simmon teaches 12-, 13- and 14-year-olds at IN-Tech Academy, a middle and high school in the Bronx. He’s been instructing five classes of about 25 students each. All city middle and high schools have been fully remote since a November shutdown brought on by rising COVID cases, although earlier this month it was announced that middle schools will return to in-person learning Feb. 25.

Simmon often thinks about the extra obstacles his students are facing this year during the pandemic.

“There’s nothing better than being face-to-face in the classroom,” he said. “For a lot of students, [remote learning] is challenging.”

Some of Simmon’s students use their cell phones to tune into class. Some have parents who don’t speak English fluently or are swamped at work, and as a result, aren’t as available to help with lessons. Some kids are sharing a single device with multiple siblings. Some don’t have good Wi-Fi. Others are dealing with a blitz of distractions at home and don’t have a quiet place to work. Others still haven’t received the support their individual education plans require. The DOE released figures last week showing one in four special education students have not received their mandated services this school year.

Like so many other teachers, Simmon has students that have grown increasingly more detached, given the now long-term lack of socialization imposed by the pandemic. He sees them tuning out — not, he said, because they can’t do the work, but because of the unprecedented time we’re living in. Many are simply exhausted.

“In the next two months, we’ll be going on a year of remote learning,” Simmon said. “A lot of kids are like, ‘Why am I doing this?'”

Modern circumstances have forced some of his students to learn almost entirely independently, he explained. “You’re by yourself, fending for yourself.”

Simmon often wonders how many of his students are passing class without fully absorbing what they’ve been taught, a reality educators will have to face when everyone returns to classrooms this fall, he said. “I hope teachers are willing to show some type of leniency in reteaching what students have lost,” he added.

In the meantime, he’s trying to provide a virtual space that feels safe and relevant.

After insurrectionists stormed the Capitol building on Jan. 6, Simmon asked his middle schoolers some guiding questions — like what they had heard and how they felt — before inviting them to lead the discussion. He used this approach after the inauguration, too.

“I give my students a lot of autonomy,” he said. “They need a voice.”

Simmon said his work in the virtual classroom has been complemented by the role his principal has played in supporting everyone through the traumatic events of the last year. Right after Jan. 6, the administrator hosted two virtual town halls — one for students, another for staff — so the community could share their thoughts.

The conversation that followed in Simmon’s classroom was impressive, the U.S. History teacher said — “Almost like a Socratic seminar. I was very proud.”

He told his students so 15 minutes in, as the chat started to wind down, adding as a reminder that the 14-year-olds present would be able to vote in the forthcoming presidential election.

“Your opinions matter,” he said. “They count.”

Then, he segued into preparing the kids for a forthcoming midterm on Reconstruction, the Second Industrial Revolution, the Progressive Era and immigration.

Simmon has long used current events to make lessons about the past resonate, and the turmoil of the last four years has made that easier. “President Trump has helped my classroom a lot,” he said with a dark chuckle.

This year alone, his 8th-graders have addressed workers rights, the exclusion of certain groups from the United States and the reasons they were kept out, and voting rights. Simmon has encouraged students to compare and contrast current events — like Trump keeping Central Americans from crossing the border — with historical ones, like the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

This year alone, his 8th-graders have addressed workers rights, the exclusion of certain groups from the United States and the reasons they were kept out, and voting rights. Simmon has encouraged students to compare and contrast current events — like Trump keeping Central Americans from crossing the border — with historical ones, like the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

He’s also used online tools, like Newsela, which covers current and historical events and has vocabulary adjustment and Spanish translation features, along with BrainPOP videos and Flocabulary lessons. And he’s replaced the traditional white board with Jamboard, where he invites students to post their ideas.

Despite these efforts, remote learning makes understanding exactly how students are receiving the material next to impossible, he said.

Simmon teaches most of class standing up, directing his attention at a grid of avatars on his screen: superheroes and anime characters, like the ones from Dragon Ball Z. About 95 percent of his middle schoolers keep their cameras off during class, he said.

“Sometimes, they’re home with Mom, Dad, little sisters, and they don’t want anyone to see their house,” he explained. “It could be laundry day, and the clothes are on the couch.”

“Of course, I would rather be physically seeing them in the classroom,” he continued. “However, we [teachers] have to be flexible. We have to adjust.”

Most of his students keep their microphones muted. When Simmon calls on them, many answer in the chat, rather than through their microphones.

He’s seen the pandemic’s impact reflected in student grades. “That student that was strong at 80, 85, may have dropped to 65, 70, even though that may not represent who that student really is,” he said. “So yes, we are losing a lot of students because of this pandemic.”

Mutual respect and trust are more important now than ever, he added. “It comes down to an honor system between teachers and students. I have to go by your word that you’re doing your work, instead of physically seeing your work … My students respect me. I have that respect, and I give it back to them.”

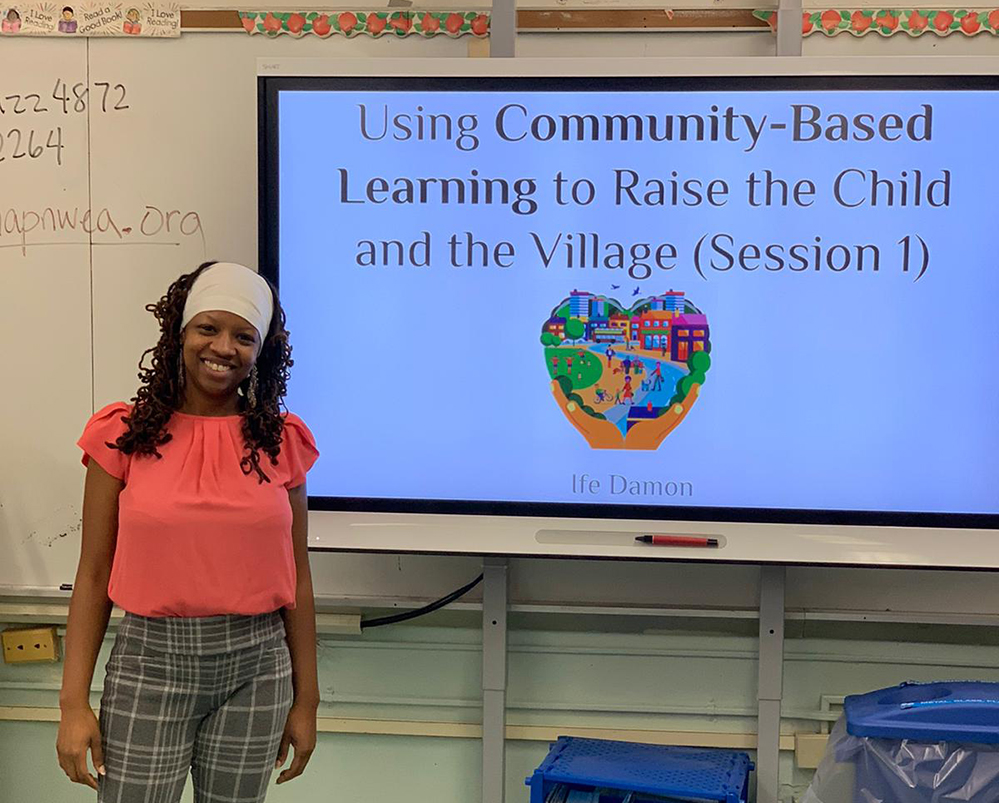

Ife Damon, high school teacher, Curtis High School, Staten Island

English teacher Ife Damon teaches five classes of 9th- and 10th-graders at one of the most diverse schools on Staten Island.

Damon, a longtime proponent of community-based learning, has seen how that approach, which connects academic content to what’s happening in students’ communities, can help teachers better understand young people at a time when they’re grappling with a profound sense of loneliness.

“When they were in school, they could see their friends in the hallways, in gym, during classes,” she said. “Once quarantine began, those friendships dissipated. This generation does have social media, but the conversational piece has kind of disappeared for many students.”

Recently, she’s found two community-based projects particularly useful in bridging the social gap created by the absence of school-based relationships.

The first, a virtual time capsule project, started in September and ended later in the fall. Damon asked her students to finish weekly assignments, which they would eventually compile into a Google slideshow for Curtis teachers to show future students in the year 2040.

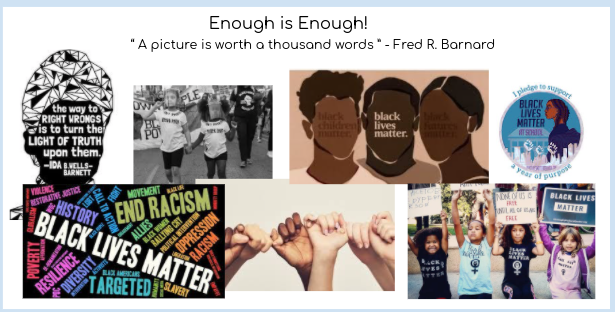

The project focused on COVID and the Black Lives Matter protests, and it helped students transition into a new school year, after they were thrown abruptly into online learning in the spring, Damon said.

“We know this is an intense time for everyone, and for kids,” she explained. “To see the level of stress and loneliness they were feeling — it was a real eye-opener.”

The English department started planning the project over the summer. The end product had built-in flexibility: some of the assignments were required, others weren’t. Teenagers were invited to write letters to their pre-COVID selves, letters to protestors, and letters to their future selves. They could interview people in their communities to learn how the people around them were being affected by COVID, quarantining and Black Lives Matter. And they were encouraged to incorporate artistic elements, like their own quarantine playlists and protest posters.

The English department started planning the project over the summer. The end product had built-in flexibility: some of the assignments were required, others weren’t. Teenagers were invited to write letters to their pre-COVID selves, letters to protestors, and letters to their future selves. They could interview people in their communities to learn how the people around them were being affected by COVID, quarantining and Black Lives Matter. And they were encouraged to incorporate artistic elements, like their own quarantine playlists and protest posters.

Damon also gave her students primary source material, like articles about Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, whose deaths at the hands of police sparked massive demonstrations for racial justice.

“We wanted to be there for students,” she said, “To give them an outlet to express themselves and develop their critical consciousness, to let them create a primary source artifact to show what’s going on, right now, in our world.”

Student reception was overwhelmingly positive. “The entire marking period was filled with good discussions,” Damon said. “I think it was a good way to start a new marking period.”

Next, Damon introduced her students to a project about dystopias, which, she said, provided a useful thematic backdrop when the Capitol was stormed in early January by far-right insurrectionists.

“We’re living in a dystopia of our own, in many ways,” she noted.

The teens were asked to choose a political issue, ranging from racism to LGBT inequality to gender inequality, and to build a fantasy world around that topic.

Each week, they finished assignments that grew their worlds further: identifying a central issue to critique, creating their protagonists and figureheads, and describing how their societies use surveillance and propaganda.

Damon gave feedback and assigned dystopian anchor texts, like stories by science fiction authors Ray Bradbury and Octavia Butler, and a few movies, like Hunger Games and Blade Runner.

It felt right to Damon that her students submitted the pitches a few days after the inauguration, given that she’s tried to use the projects to offer students some hope.

“I tell them I’m looking forward to happy endings,” she said. “I want them to feel that things can get better — not that society has to stay as dystopian as it’s been.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)