Nearly a Year Into Remote Learning ‘Digital Divide’ Persists as Key Educational Threat, as Census Data Show 1 in 3 Households Still Struggling With Limited Tech Access

Mariah Hawkins wants to become a nurse.

At 15, she is a 9th-grade student at iLEAD Academy in northern Kentucky, a selective regional high school where students take college-level courses in preparation for fast-growing STEM careers. In December, the school received a $100,000 grant through the U.S. Department of Education’s Rural Tech Challenge.

Yet just halfway through her freshman year, Hawkins is afraid of failing out, not because the work is too hard, but because she does not have reliable internet access.

“I’ve never had an F in my life, I’ve always had all As or maybe a B if I was struggling real bad,” she said. “I have a low D or an F in algebra right now, and I’m telling you, if I could go back to school, I could bring that right back up. Most of my problem is I can’t get my stuff to submit all the way because my WiFi is completely terrible.”

Unfortunately, Hawkins is not alone. According to a report released last month by UCLA, nearly one in three American households had limited computer or internet access this fall, more than half a year after the pandemic erupted. The report, which is based on a weekly survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, sheds new light on an old problem. As was the case before the coronavirus crisis, students of color, students from low-income households, and students whose parents earned a high school diploma or less are most likely to be on the wrong side of the digital divide, making it more difficult for them to access their classes, engage with peers, and complete their assignments.

“You can think about all of these things that by themselves may not seem absolutely fatal, but collectively it has this cumulative effect that eventually leaves certain students behind,” said Dr. Paul M. Ong, the director of the Center for Neighborhood Knowledge at UCLA and author of the report.

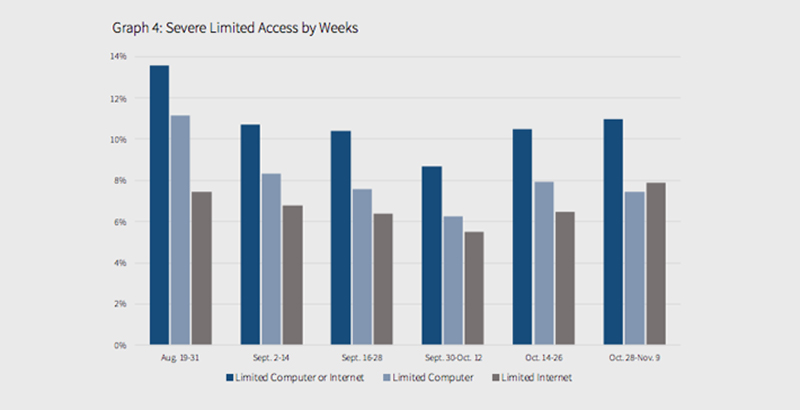

The report shows that lack of access to functioning devices and internet ebbed in September and the first part of October as more students began returning to their school buildings. But in recent weeks, as rising coronavirus numbers have led some of the largest school districts in the country to again shutter their buildings, the issue has taken on renewed importance.

Tens of millions of students are accessing school from a device while at home, and grades for this fall suggest many students, like Hawkins, are having trouble. In Houston, 42 percent of students received at least one failing grade. In Virginia’s Fairfax County, the percentage of middle school students with two or more failing grades tripled, with Hispanic students, students with disabilities, students learning English, and students from low-income households struggling the most.

In December, Congress considered providing funding to help students from low-income households access the internet, but negotiations broke down. Ultimately, funding to support the estimated 12 million children with little or no internet access was not included in the final $900 billion pandemic relief bill, despite bipartisan support.

“The pandemic didn’t create the homework gap,” Noelle Ellerson Ng, of AASA, The School Superintendents Association, told U.S. News. “The pandemic just ripped it wide open. It was education’s worst-kept secret, and now it’s out in the limelight and somehow still able to be ignored.”

States and school districts have assembled a patchwork approach to supporting students in the interim. Some districts parked WiFi-enabled buses in neighborhoods with less internet access. In early December, Connecticut announced it became the first state in the country to provide a “learning device” to every student, using $24 million in philanthropic support and $43.5 million from the state’s bucket of CARES Act funding. Of course, scale is an issue, and the 141,000 laptops that Connecticut acquired would only serve 12.5 percent of the students in New York City, where some 60,000 students still lacked devices more than eight months into the crisis.

Ong notes that his report does not focus on the effects of limited access, although the implications are clear, and concerning. The report shows, for instance, that students in homes where computers are not always available interact less with their teachers and do homework less often, suggesting that learning loss is likely to follow.

That’s the outcome Hawkins, the Kentucky 9th-grader, fears most. She started falling behind in September, when she had COVID and was hospitalized for three days. It’s been a struggle to catch up ever since.

She splits her time between her divorced parents, with her mom’s house in a rural area beyond the reach of any internet service provider and the internet at her dad’s house so slow as to be nonexistent. Her mom paid $400 to get a wireless hotspot from her school, but Hawkins said it can’t find a signal, rendering it useless.

As a result, Hawkins said she frequently cannot log-in to the live lectures her teachers deliver via video while her school building is closed. She is often unable to upload her completed assignments, too.

Jenna Gray, the school’s director, is aware of the challenges Hawkins faces and said, “We’re going to work with her to find solutions.” In the meantime, Hawkins is afraid she is falling behind in the school’s ambitious quest to have students earn an associate’s degree by the time they graduate from high school.

“There’s nights where I just cry because, like I said, I’ve never had an F in my life,” she said. “It’s risky for me.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)