‘Inequalities Grow Before Our Eyes’: Alarming New Data Show Ohio’s Black Students Have Lost a Half-Year of Learning, Are Missing More School, During the Pandemic

Black students are faring far worse during the pandemic than others, new test data out of Ohio show, with COVID-19’s disruptions setting them back as much as a half year’s worth of learning and widening longstanding racial achievement gaps.

The results of Ohio’s fall 2020 third grade reading tests offer a dire warning on the damage the pandemic could inflict on students across the country, particularly minority students.

“We are seeing existing inequalities grow before our eyes,” said Ohio State University professor Vladimir Kogan, who estimated that students across Ohio have lost a third of a year of learning on average, while Black students have lost half a year. “I think it calls for us as a state to respond.”

His analysis also estimated a half a year’s decline in districts or charter schools where classes were forced online – most of which were in Ohio’s heavily-minority cities. And he found test score declines in counties where increases in unemployment created economic shocks for students like hunger, evictions and loss of WiFi, an academic lifeline during school shutdowns.

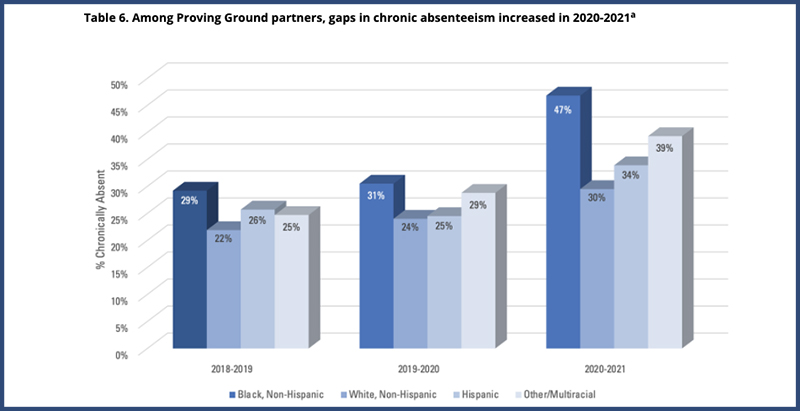

The racial gaps could grow even worse as the school year continues, other data released by the Ohio Department of Education last week suggests. Chronic absenteeism across all grades, a problem that invariably damages test scores, grade promotion and even the likelihood of students eventually graduating, has soared since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, with Black students once again faring far worse than others. Nearly half of Black students were chronically absent in a sample of 10 districts released by the state.

Ohio defines chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of a school year.

“Those gaps could be going from terrifying to absolutely astronomical,” said Dave Hersh, director of Proving Ground, a Harvard University program working with schools in Ohio and other states to improve attendance and student learning.

While all groups of students – white, minority, urban and rural – saw chronic absenteeism rates rise, the rate of chronic absenteeism for Black students jumped more than twice as much.

Chronic absenteeism among Black students leapt 18 percentage points – from 29 percent two years ago to 47 percent so far this school year in districts that include the high-poverty and mostly-minority Cleveland suburbs of East Cleveland and Maple Heights,

White student chronic absenteeism rose just eight percentage points – from 22 percent to 30 percent – in the same time frame, with Hispanic and multiracial students falling in between.

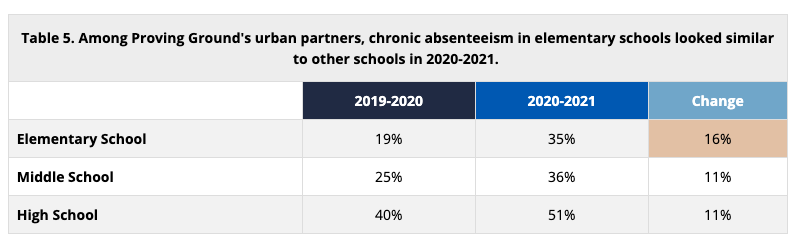

In addition, 51% of all students in urban high schools in Proving Ground were chronically absent, up from 40 percent last year.

“The gaps were scary before the pandemic,” said Hersh. “If these ratios hold, those gaps are so big now we’re talking about sort of game-changing efforts needed to start addressing them.”

Hedy Chang, whose national organization Attendance Works also works with Ohio schools on absenteeism, called the data “pretty sobering.”

“African American students who faced barriers to attendance prior to the pandemic are even harder hit by the pandemic,” said Chang. “[That] has made it even harder to get an equal access to quality education, whether that is because they have less access to technology, are more likely to live in poverty so (they are) less likely to have the space at home to create a quiet place to be learning and are more likely to be challenged by lack of food, greater mobility, unstable housing and less access to health care.”

The Ohio Department of Education released the early test data, the chronic absenteeism rates and an estimate of enrollment changes during the pandemic as an early look at how COVID has affected students in the 20-21 school year. More detailed data will be available in the state’s annual school report card in September.

The data also comes just as teachers across Ohio start receiving vaccinations and Gov. Mike DeWine presses schools to open for in-person classes by March 1.

DeWine said last week that he decided long before the data was available that students need to be back in school, but it confirmed his desire to reopen schools quickly.

“There were a lot of kids that were just not doing very well in this total remote system…there are kids who are behind, were already behind and are getting much farther behind,” DeWine said. “It’s very worrisome. I think it was a crisis, frankly, and I feel like I had to take action to stem this crisis.”

Ohio’s results avoid some of the issues that limited what could be drawn from results released late in the fall from commercially-produced diagnostic assessments like i-Ready and NWEA Map.

While the percentage of Ohio third graders taking the test dropped from 95 percent last year to 81 percent this year, they still assessed the majority of students statewide. And because students had to take the tests at school, that wiped out concerns plaguing the other tests that parents were coaching their children as they took them online at home.

“There’s some things that are unique to this study relative to the other measures of learning loss that we’ve seen that affirm that learning loss is a real thing, that it’s not just associated with non-state assessments, that it is not just associated with tests that are administered in odd ways,” said Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Education Data and Research at the University of Washington.

“We’re likely to see learning loss across the board and the learning loss is going to be particularly bad for disadvantaged students,” he said.

Ohio’s reading results show a seven percent drop – from 44 percent in 2019 to 37 percent in 2020 – in the percentage of students scoring above the state’s “Proficient” score of 700. That’s the lowest percentage in at least the last four years, though 2019 had higher scores than typical.

The state did not release the average scores of students on the tests or how test scores changed by race.

Kogan and fellow Ohio State University professor Stephane Lavertu went a step further by calculating losses for different groups of students using scores for individual students, combined with student scores from second grade reading diagnostic tests given last fall.

The calculations aren’t simple and rely on earlier research estimating that students generally have an improvement in test scores of 0.6 standard deviations from second to third grade. With that as a reference, he and Lavertu found that scores this fall fell short by different amounts for different races.

Students overall were down 0.23 standard deviations and white students down 0.2 standard deviations – about a third of a year. Black students were down 0.3 standard deviations, about half a year.

“It’s just a ballpark estimate to give people an idea in relative terms,” said Kogan.

They also estimated that while the white student proficiency rate fell by 8 percentage points, the Black student proficiency rate fell by 12 percentage points.

And they said that schools that have been 100% remote all year lost more ground than schools that had all or some in-person classes.

They found:

100% in person schools: -0.182 standard deviations (~1/3 of a year)

Hybrid/mixed: -0.233 standard deviations (somewhat more than 1/3 of a year)

100% virtual: -0.278 standard deviations (almost half a year)

Kogan, who has been pressing schools to reopen on social media in recent months, said the pattern is clear but hesitated to say remote learning is causing the drop.

“I think we want to be careful about that,” he said. “Can we be sure that it’s just remote learning? Or is there something else going on? We can’t rule that out at all.”

They also found that student scores in counties where unemployment rates rose during the pandemic declined more than in places with low unemployment changes. Loss of family income and the economic instability, lack of food, heat and internet that unemployment can bring have long been associated with lower student grades and students having to repeat a year of school.

Kogan said he hopes to use more detailed unemployment data to look at individual districts soon.

Kogan and Lavertu’s results also try to compensate for a problem hurting other measures of learning loss – the large numbers of poor and minority students not coming to schools that were otherwise closed just to take the tests.

Cleveland, a high-poverty and mostly-Black district, for example, had 89 students take the test this fall after more than 2,600 took it in 2019. The district had the worst participation rate of the more than 600 districts in the state.

Columbus had about a third as many third graders take the tests as last year.

So Lavertu and Kogan adjusted statewide estimates by using fall scores of students in other cities whose earlier test scores and socioeconomic backgrounds matched those of the missing students.

Natalie Spievack, a researcher with the Urban Institute, said the findings in Ohio and from other tests suggest that generations of families could be hurt by school disruption from the pandemic. She said that if gaps like those in Ohio stand up to future testing, it could have long-term impact on students’ learning, likelihood of earning college degrees and their lifelong income.

“We can’t understate how worrisome and concerning the scale of the learning losses we are expecting to see are, and the size of the racial and ethnic gaps in those learning losses,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)