Lessons from an Insurrection: A Day After D.C. Rampage, How 15 Educators From Across U.S. Helped Students Make Sense of the Chaos

Teachers across the country faced their students Thursday with a gut-wrenching task: Talking to them about the violent insurrection that unfolded at the U.S. Capitol less than a day before.

In D.C., where the breach of the Capitol building by pro-Trump supporters falsely claiming election fraud was in teachers’ and students’ own backyards, one educator drew historical parallels to white aggression at Woolworth lunch counters. A Minnesota teacher’s class discussed the limitations of the First Amendment. Students in both a Colorado and New York City educator’s class compared Wednesday’s police reactions to those of the Black Lives Matter protests last summer.

“There need to be lessons, [class] discussions about what is happening right now. What led up to this,” Washington Teachers Union president Liz Davis told The 74. “Because it didn’t happen in isolation.”

The 74 interviewed teachers nationwide about how they would present Wednesday’s events and the lessons they’re hoping students take away from those discussions.

Angelo Parodi, 5th-grade social studies, John Eaton Elementary

Washington, D.C.

Parodi wanted his students to know while these times “can be very fearful and scary, there are always people who will stand up and speak to the right thing.”

On Thursday he had them read texts bolstering that message: Robert F. Kennedy’s speech the night of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. ‘For My Young Friends Who Are Afraid’ by poet William Stafford.

The most recent example they discussed, Parodi added, happened Wednesday: When Congress, in spite of the insurrection, resumed to certify Joe Biden’s election win. “They didn’t let anything, not even a civil war, stop them,” Parodi said. “That is something to be proud about.”

Kara Cisco, Minnesota 2020 Social Studies Teacher of the Year, ninth-grade civics, St. Louis Park High School

St. Louis Park, Minnesota

“The use of force — in particular the use of tear gas, rubber bullets, flashbangs, grenades — was exponentially faster in Minneapolis,” where many of Cisco’s students experienced police violence during protests following the killing of George Floyd, than after the breach of the Capitol. This, she said, “adds an additional layer of complexity to my job, which is helping students parse that out, within the context of the Constitution. We’re constantly going back to, in this case, the First Amendment and what is clear and present danger, what are the words and what are the limitations of freedom of speech?”

“The use of force — in particular the use of tear gas, rubber bullets, flashbangs, grenades — was exponentially faster in Minneapolis,” where many of Cisco’s students experienced police violence during protests following the killing of George Floyd, than after the breach of the Capitol. This, she said, “adds an additional layer of complexity to my job, which is helping students parse that out, within the context of the Constitution. We’re constantly going back to, in this case, the First Amendment and what is clear and present danger, what are the words and what are the limitations of freedom of speech?”

While some teachers in other districts were directed to “maintain a position of neutrality,” she instead chose to start conversations “rooted in criticality,” she said. “The questions that we pose as teachers are powerful in that they invite students to develop their own critical consciousness and their critical thinking skills in unique ways. Our power lies not in telling, but in asking big questions, and inviting students to engage…. Being a teacher is such a privilege right now because I have the ability to process this with students in a way that the average person doesn’t. … Does law enforcement perceive Black bodies to be dangerous before they perceive white bodies to be dangerous?”

Christine Montera, 11th-grade U.S. history, East Bronx Academy

New York City

Montera was up all night Wednesday, trying to figure out which “anchor texts” to use to teach her three classes about the day’s nightmarishly surreal events, while also worrying about the ways to break through the barriers of remote learning on such a sensitive topic.

“As a white person and teacher, I always have a lot of concerns about me not hurting them more,” she said. “I try to get a read on where they’re at because I can’t — I won’t pretend to know what their experience of this is.”

The teenagers said they were angry and frustrated — one said they felt hopeless, she said. All of them asked, “What would have happened, if this had been Black people?”

Montera addressed the stark differences in the ways law enforcement and government officials reacted to the Black Lives Matter protests over the summer, versus yesterday’s white-led insurrection. She’s not sure what, but plans to come up with an action plan her students can execute moving forward so they don’t feel so powerless.

“I personally think that it’s my duty as a U.S. history teacher to talk about these things and address them. I hope that other teachers see it the same, especially teachers of students who are white, and in different places, not just the South Bronx where I teach, but in places where this could make a difference.”

Cosby Hunt, AP U.S. History and D.C. History teacher, Thurgood Marshall Academy

Washington, D.C.

Hunt was still processing Wednesday’s events later that night. “I’m mad, really mad,” he wrote in an email. But he already had plans for Thursday’s classes: “In D.C History, we’ll talk about the parallels between the ‘mutiny’ of Rev[olutionary] War veterans in 1783 and what happened today,” he said.

“In [A.P. U.S. History], I think I’m just going to open up the floor to students sharing what they’re thinking and wondering. I may do free write with sentence starters like: ‘I saw… I heard… I’m feeling… I wonder about …’”

Dale Fraza, social studies, 360 High School

Providence, Rhode Island

Fraza opted to begin his lesson today by underscoring the gravity of Wednesday’s events.

“I’m going to start by addressing that January 6th, 2021, will be a date that we study 15, 20, 50 years down the line,” he told The 74 Wednesday night.

Fraza said he would invite questions and concerns then would use disturbing photos and video clips of the mob overrunning the Capitol to prompt student discussion in breakout rooms online. He plans to close by examining statements from public figures, such as former President Barack Obama and President Donald Trump, who now faces the prospect of a second impeachment or being removed from office via the 25th Amendment.

His 360 colleague, Kelly McGahan, who said she quickly “chucked my other lesson plan in favor of covering this current event,” used those same photos to prepare her own “See, Think, Wonder” exercise for her classes.

Maya Chavez, a civics teacher in the city’s Jorge Alvarez High School, planned an optional afterschool Google Meet session for students wanting to talk and also revised her lesson plan, titling it simply: Crisis in Democracy.

Laura Tavares, program director for Facing History and Ourselves

Boston, Massachusetts

Students need to process their emotions about Wednesday’s events to understand the political ramifications of them, said Tavares, who helped create a lesson teachers anywhere can use that already has 100,000 views online. The lesson, “Responding to the Insurrection in the U.S. Capitol” suggests questions teachers can ask to draw students out, like:

- How do you feel about the insurrection and what is happening in the aftermath?

- What questions about right and wrong, fairness or injustice, did insurrection raise for you?

- How should individuals or politicians act in order to protect our democratic institutions?

“It’s good practice to make a reflective space before we dive more deeply into other questions,” she said. “We feel a need to balance the head and the heart and also ask questions about ethics and behavior.”

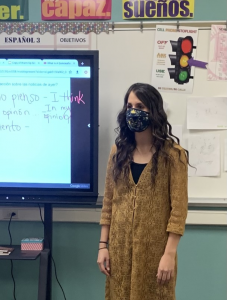

Cassandra Garcia, Spanish, Central High School

Rapid City, South Dakota

As a high school Spanish teacher in rural South Dakota, Garcia lost sleep wondering how to address the news in a community where more than 60 percent of residents voted to reelect President Trump. Ultimately, she decided that the lessons were too pertinent to skip.

“I couldn’t ignore it and I had to provide an opportunity for these young minds to process and express their reactions,” said Garcia, whose own community was subjected to social unrest last summer when Trump delivered remarks at nearby Mount Rushmore in July. To address Thursday’s violence, Garcia highlighted how the mayhem was covered by newspapers in Spain, Mexico and Colombia, giving students an opportunity to learn new Spanish vocabulary, including violenta (violent) and revuelta (revolt).

“I definitely sent the message that responding with anger in the way that these people did is not appropriate,” she said. “It’s OK to have different opinions and it’s OK to be in two separate political parties, but the more important thing is that we know how to communicate and that you listen to each other.”

But in addressing the incident, she also felt a need to tread lightly.

“I don’t want parents to think that I’m influencing how their children are thinking in terms of one side versus the other — but more just on how to be a good person,” she said.

Rob Manuel, World History teacher at KIPP DC College Preparatory

Washington, D.C.

Manuel said while he “can appreciate” pundits’ and reporters’ “disgust in the hypocrisy in the [Metropolitan Police Department], National Guard, and Capitol Police responses” Wednesday as opposed to last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, he’s decided to draw alternative comparisons when he resumes classes on Friday. (KIPP DC cancelled virtual class for Thursday).

“Instead of comparing what WOULD have happened if the rioters were black,” he wrote in an email, “I plan to …. compare [Wednesday’s events] to every other instance in which a group of people (especially white people) feel themselves losing the grips of power. Instead, I will push my students to compare this moment with the futile anger, aggression, and hatred seen at the Woolworth Lunch Counters, the destruction of Black Wall Street, and the actual secession of southern states to protect their right to own human beings.”

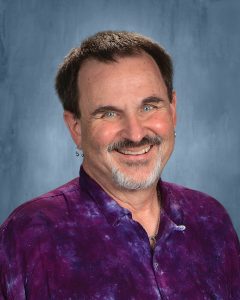

Anton Schulzki, teaches “History of the Americas,” William J. Palmer High School

Colorado Springs, Colorado

A veteran social studies teacher, Anton Schulzki has had to face his students after multiple crises and rough points in the nation’s history — the Challenger disaster, school shootings, impeachments and wars. But Wednesday’s breach of the U.S. Capitol was different. “I could see their faces, but it’s hard to gauge reactions in a virtual room,” said Schulzki. Republican Doug Lamborn, who represents that part of the state, is one of the House members who objected to the election results.

A veteran social studies teacher, Anton Schulzki has had to face his students after multiple crises and rough points in the nation’s history — the Challenger disaster, school shootings, impeachments and wars. But Wednesday’s breach of the U.S. Capitol was different. “I could see their faces, but it’s hard to gauge reactions in a virtual room,” said Schulzki. Republican Doug Lamborn, who represents that part of the state, is one of the House members who objected to the election results.

Several students pointed out differences between police reaction to the men and women storming the Capitol and those participating in Black Lives Matter protests over the summer. “They said, ‘No one is getting beaten up,’” Schulzki said. One student, troubled by the “entirety of the chaos,” had to excuse himself from the class, Schulzki said. He checked on him later in the day, when the student told him, “I don’t do well in those situations.”

Cody Norton, 3rd-grade English language arts, Marie Reed Elementary School

Washington, D.C.

“Students were very angry, they were very uncomfortable and very sad,” said Norton, who let part of Thursday’s class be a place for students to talk about their emotions. And “they wanted to have questions answered about why the riots were taking place, the motivation of why the police response was different from racial justice protests they’ve seen. … Just clarification on what was happening in their city, very close to their homes and their neighborhoods.”

Norton also guided class discussion toward “definitions of power. Thinking about power as a mechanism of control, where power is a limited resource and it’s used to dominate, and wanting to move our thinking to power as a means of liberation, where we’re trying to build a collective community that’s working toward the freedom of all. … [In that vein,] Students talked about reducing gun violence. One student in particular mentioned that one way to build power and to keep people safe is thinking about the ways communities are policed.”

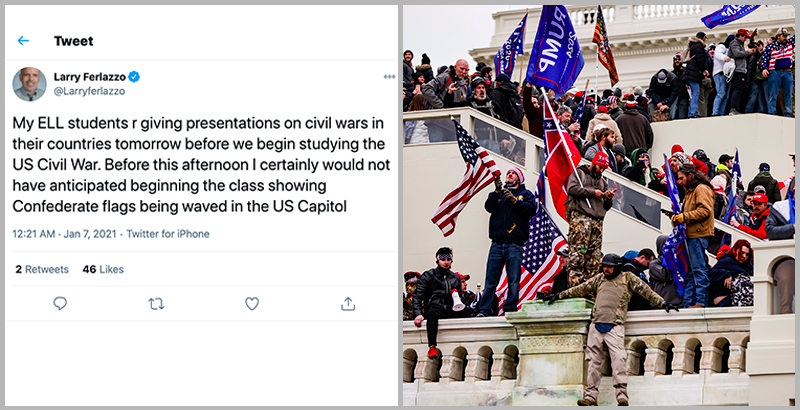

Larry Ferlazzo, social studies teacher, Luther Burbank High School

Sacramento, California

In the Sacramento Unified School District in California, Larry Ferlazzo’s English learner students were preparing to give presentations Thursday on civil wars in their home countries. “Before this afternoon I certainly would not have anticipated beginning the class showing Confederate flags being waved in the U.S. Capitol,” tweeted the English and social studies teacher at Luther Burbank High School.

Elizabeth Clay Roy, CEO of Generation Citizen

New York City

While Roy isn’t a teacher, the civics education nonprofit she heads is “developing resources for our educators by Friday morning,” she wrote in an email. One critical tip for teachers in wake of Wednesday’s events, Roy said, is that they “connect with families so that students feel supported by all of the adults in their life. Especially in the context of remote learning, it is important that parents know how this moment is being discussed in the classroom so they can invite their children to continue the conversation.”

While Roy isn’t a teacher, the civics education nonprofit she heads is “developing resources for our educators by Friday morning,” she wrote in an email. One critical tip for teachers in wake of Wednesday’s events, Roy said, is that they “connect with families so that students feel supported by all of the adults in their life. Especially in the context of remote learning, it is important that parents know how this moment is being discussed in the classroom so they can invite their children to continue the conversation.”

Nikki Bartlett, English teacher, Newcastle Middle School

Newcastle, Wyoming

In the state where voters handed Trump’s reelection bid the nation’s largest margin of victory against President-elect Joe Biden, Bartlett largely avoided teaching about Wednesday’s insurrection — in part because it was being discussed in social studies class. But also because she was nervous.

“It interrupts my curriculum and I was worried about where it would go,” said Barlett, who acknowledged the topic did wind up in conversations during several classes on Thursday. “I was a little nervous to even field all of the questions.”

While some students mentioned voter fraud and Biden’s potential effects on firearm laws, discussions remained civil and most students were confused by what had transpired. One student’s inquisition gave her goosebumps, she said.

“She goes, ‘I don’t get why they can’t just accept it, numbers are facts,’” she said. “I wanted to hug her, but COVID, and I wanted to applaud her, but I couldn’t. I just had to remain pretty neutral, which was the hardest part through it all. I said, ‘Absolutely, you are dead on.’”

74 reporters Taylor Swaak, Laura Fay, Beth Hawkins, Linda Jacobson, Mark Keierleber, Zoë Kirsch, Patrick O’Donnell and Asher Lehrer-Small contributed to this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)