Investigation: Overshadowed by Shocking Abuse and Misconduct Cases, Teacher Incompetence Often Harms New York City’s Poorest Students

New York City brought incompetence charges against 80 tenured teachers during a 16-month period in 2015 and 2016, many of them working in the city’s poorest neighborhoods at low-performing schools with large populations of homeless and chronically absent students.

Arbitrators agreed to terminate 52 of the ineffectual educators for failing to provide students with “a valid educational experience” despite repeated efforts by their schools to help them improve. Another 27 were fined or suspended, according to teacher disciplinary records obtained by the The 74. Fines ranged from “three days’ pay” to $10,000, while the shortest suspension was 20 days and the longest was “not less than 9 months.” One teacher was exonerated.

While cases of flagrant misconduct and physical abuse by teachers sometimes become public, stories of incompetence almost never do. The 74’s sample concerned a tiny fraction of the city’s 58,000 tenured educators, but the cases often document how schools that are under duress handle their worst performers. Arbitrator decisions — sometimes exceeding 100 pages — open into broad view the city’s effort to ensure students have good teachers, particularly in areas where educators don’t usually stay for long.

“The stuff that gets covered in the [New York] Post is just the salacious stuff,” inevitable in so large a teaching force, said David Brodsky, head of labor relations at the Department of Education in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s final term, referring to tabloid reports about outrageous misconduct cases.

“To me, how you punish incompetence deserves a close look,” he said.

Tougher teacher evaluations not at play

In April 2016, The 74 requested under the state Freedom of Information Law decisions from disciplinary hearings where New York City moved to fire tenured teachers. The DOE, recently taken to task for repeated delays in its response to public records requests, extended its initial deadline 25 times over 28 months before providing a complete set of records in August.

The cases addressed activity between 2011 and 2015, a challenging time in many city classrooms because more difficult reading and math standards, as well as a controversial new model of assessing teachers, were being implemented.

Those changes occasioned raucous political battles across the state, but arbitrators rarely found that they accounted for unsatisfactory performance.

“I am not persuaded that the implementation placed any significant new burdens on teachers,” a hearing officer who dismissed a teacher’s claim wrote of the state’s detailed new approach.

Many educators found unfit for their positions worked in schools whose struggles went beyond unfamiliar performance measures. Concentrated in high-poverty districts in the Bronx and central Brooklyn, nearly 1 in 3 of those brought up on incompetence charges taught in schools that subsequently closed or were tagged for turnaround by city and state officials.

While too few to support broad conclusions, the numbers are expressive. Among the 80 teachers in The 74’s incompetence sample, one-fifth (16) worked in the city’s five poorest school districts, which educate about 9 percent of all students. Twenty-two taught in districts whose students were absent an average of 45 days or more.

They taught at all grade levels and in subjects ranging from reading to Latin and business. Some had taught for decades and never been disciplined; some had been assigned to or selected from the city’s Absent Teacher Reserve, a pool of educators who have lost their permanent positions due to budget cuts or disciplinary charges.

Men were overrepresented: they comprise 23 percent of all New York City teachers, according to the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, but made up 35 percent of teachers facing incompetence charges (27 of 77 whose gender was identified).

Two deans were among those charged, as were at least five teachers who served as their schools’ union representative. One led adult education classes at a learning center above a Rite Aid in Flushing, Queens.

Working in high-poverty schools is known to be challenging for almost any educator, but the city argued that teachers brought up on charges were deficient at basic tasks like planning lessons — a problem in nearly every case — or grading student work (one teacher refused to provide her class’s assessment results, storing them at home).

Others failed to give intelligible or accurate information. One told students “all pine trees in New York are bought in stores.” An earth science teacher who insisted her lesson was successful did not notice that most students left believing leeches, rather than leaching, provided nutrients for soil.

As poor evaluations and disciplinary letters mounted, teachers became more likely to lash out at superiors and to act in erratic ways in class. In some instances, they stopped coming to school.

Their shortfalls couldn’t be ascribed to inexperience. On average, those charged with incompetence had taught in the city for 18 years at the time of their hearings, compared with an average of a little less than 11 years for all teachers, according to a 2014 report by the city’s Independent Budget Office. While the DOE redacts names in incompetence cases, the annual salary of a 18-year veteran with a master’s degree was $96,362.

“It’s really hard to get teachers to change as students’ needs change,” said Kathleen Elvin, who took over as principal at John Dewey High School when it was then slated to close in 2012. She brought incompetence charges against several teachers, including two in The 74’s sample (one was terminated and the other was suspended for nine months).

The school’s population had changed, she said, becoming less “college-specific.”

“Many [teachers] kept doing the same things as they had in the past,” she recalled. “In their heads, they were very, very effective teachers because they always had been.

“If you spent 15 years and all of a sudden someone is telling [you] to change, it’s really hard.”

Dewey remains open, but Elvin was assigned to an administrative office when grade-fixing allegations were leveled against her. She was later cleared.

Seeking accountability for bad teaching

In 2007, DOE attorneys in the newly created Teacher Performance Unit began working with school administrators to build cases against chronically inadequate educators.

“Nobody was ever prosecuted just for being bad teachers,” Brodsky said. “There was absolutely no accountability about whether a teacher can actually teach.”

The teachers union was furious. Randi Weingarten, then president of the United Federation of Teachers, told The New York Times that the city was “signaling to principals that rather than working to support teachers, the school system is going to give you a way to try to get rid of teachers.”

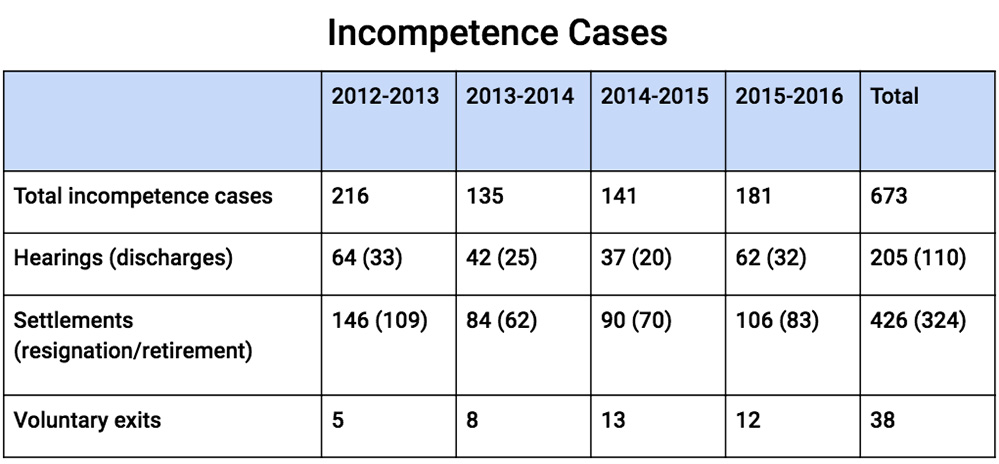

The relatively small numbers charged with incompetence seem to belie union fears. Of the 205 educators between 2012-13 and 2015-16 who elected to fight incompetence charges before an arbitrator, 100 were fired and the rest received lesser penalties.

Another 426 settled with the city during that time, and three-quarters of those agreed to leave the school system by resigning or retiring.

“We are always looking for ways to make the process even faster while preserving its fairness,” said Adam Ross, the UFT’s general counsel. “We can’t comment on individual cases, as it is the role of the neutral arbitrator to weigh all the evidence and then make a fair determination.”

The total number of incompetence cases brought annually between 2012-13 and 2015-16 ranged between 135 and 216. The numbers under Mayor Bill de Blasio were consistent with those under Bloomberg.

“We have clear policies to ensure great teachers are in every classroom and to move teachers who should be teaching out of the system,” said Doug Cohen, a DOE spokesman. “Every year, we use all the tools at our disposal to address any case of employee misconduct or incompetence, and the number of cases closed changes from year to year.”

Remediation sometimes futile

Most of the teachers the city sought to terminate in The 74’s sample had received ineffective ratings for two or more years, often both before and after 2013, when the city implemented a new evaluation system that for a few years incorporated student scores on state tests. State leaders adopted the measure earlier in order to qualify for federal grant money under President Obama’s Race to the Top initiative.

In many cases where arbitrators ruled in favor of dismissal, poor performance in the classroom was exacerbated by a refusal to accept the school’s offers for help, dozens or even hundreds of missed or late days, and sometimes flagrant insubordination, in the view of arbitrators.

Eric Nadelstern, a longtime principal before rising to deputy chancellor under Bloomberg, said he didn’t try to rehabilitate his worst teachers.

“When principals spend time to document a case, they aren’t able to work with effective teachers, which would give you a better bang for your buck,” he said. “I prefer to spend my time with 98 effective teachers than two really bad ones.”

In several cases, arbitrators found that time spent supporting incompetent teachers was futile.

Despite 10 unsatisfactory evaluations, a record of leaving class to talk or play games on her Blackberry, and falling 57 classes behind in preparing required lesson plans, an earth science teacher at University Neighborhood High School in lower Manhattan flamboyantly refused remedial help. When given materials for PIP Plus, a remediation program aimed at teachers in danger of facing charges, she dropped the materials in the trash in front of supervisors.

In another case documenting classroom shortcomings compounded by erratic behavior, an Upper West Side K-1 teacher was absent for nearly half of the 2013-14 school year and stopped coming in at all after late May, apparently to avoid a meeting with the principal. Her students “lagged behind the other kindergarten students in the math curriculum,” the arbitrator found.

These teachers and others accused supervisors of working to undermine them. Arbitrators repeatedly found conspiratorial accusations to be groundless — including a claim by the teacher who was 57 lessons behind that she faced “a continuing retaliatory harassment campaign.” But the anger among many of the teachers was sometimes difficult to separate from the culture of stressed schools and workplace antagonisms, often playing out in a fugue of grievance filings and disciplinary letters.

Many of the schools were in crisis. In a few cases, principals faced cheating or misconduct scandals of their own. Sometimes a new principal imposed unfamiliar routines on a recalcitrant staff. More than one veteran teacher brought up on charges accused the school leader of “micromanaging.”

“Not letting your first-graders take a nap in the middle of the day, that’s not micromanaging,” a new principal assigned to a struggling school testified in one case. “Observing lesson plans, or doing lesson observations, is not in any way, shape, or form micromanaging, and yet the staff definitely thought it was micromanaging when I did those things.”

Seven of the schools that were home to educators charged with incompetence subsequently closed, one merged, and nine were identified as among the state’s most struggling. Eight more were assigned to Mayor de Blasio’s Renewal program, which sent roughly $600 million in extra resources to low-achieving schools but has not lived up to the mayor’s promises.

“Everyone acknowledges the ‘dance of the lemons’ in which low-performing teachers are moved from school to school,” said Dan Weisberg, president of the reform advocacy and teacher training group TNTP and a former DOE labor relations head under Bloomberg. “But we don’t acknowledge where the dance almost always stops: at schools with kids of color and kids from poverty.

“If you’re indifferent to this issue,” he said, “you’re indifferent to equity.”

Disclosure: David Cantor served as the Department of Education’s press secretary under Mayor Michael Bloomberg from 2005 to 2010.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)