Investigation: New Records Reveal What It Takes to Be One of the 75 NYC Teachers Fired for Misconduct or Incompetence Between 2015 and 2016

Seventy-five tenured teachers found guilty of abuse or incompetence — many of them male, veteran educators assigned to struggling New York City schools — were fired over 16 months in 2015 and 2016, an analysis of disciplinary records obtained by The 74 has found.

Educators were terminated for choking students, publicly taunting children who couldn’t read, and, in the case of one Brooklyn technology teacher in 2011, threatening to “shoot up everyone” at a school. But the majority were found by their schools to be inadequate as instructors.

Department of Education lawyers prosecuted 154 schoolteachers in all during this period — a tiny fraction of the city’s 58,000 school staff with tenure. For critics, the total suggests that many who are unfit have been allowed to remain in classrooms. Others believe relatively few teachers merit termination.

Eric Nadelstern, a deputy chancellor under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who once suggested that “one-third to two-thirds” of the city’s teachers were not up to par, said the number of teachers prosecuted is “a small slice of a much larger problem.”

The decisions appeared both to corroborate and confound claims about the difficulty of removing unfit educators protected by tenure from public schools. In one case, a middle school teacher kept his job despite three years of poor ratings after it was determined some of his evaluations had not been completed properly. A veteran French teacher who flirted with and touched a student received a relatively light six-week suspension because it was his first offense.

Nearly every case involving physical contact or verbal abuse ended in termination, however, giving little support to the idea — fostered by a few high-profile examples — that heinous offenders frequently return to classrooms.

The teachers in The 74’s sample were disproportionately male and long-serving, many in the city’s poorest districts in the Bronx. Forty-one worked at schools that later closed or are currently targeted for closure or turnaround by state and city officials.

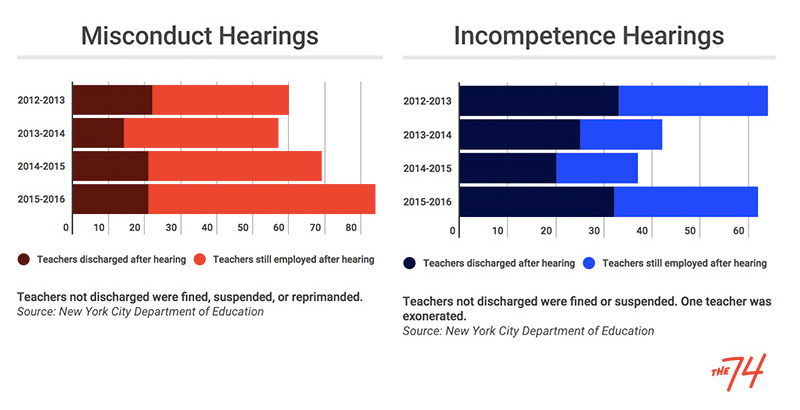

As tenured employees, they had the right under state law to contest the city’s allegations before independent arbitrators in hearings that resemble trials, with procedures governing evidence, witnesses, and cross-examination. About half — 75 teachers — were terminated, including 52 for incompetence. Nearly all who survived dismissal were fined or suspended.

Three teachers received written reprimands. A principal was demoted for a year to assistant principal. One teacher was exonerated.

In 2016, The 74 requested the records, which are public, under the state’s Freedom of Information Law in order to ascertain whether the teachers contract that was signed in 2014, and which included a more extensive description of misconduct, had affected arbitrator decisions. The DOE extended its deadline for delivering the materials 25 times and didn’t send a complete set until last month. The department also provided statistics at The 74’s request detailing how teachers were disciplined between the 2012-13 and 2015-16 school years.

In each of those years, arbitrator rulings accounted for fewer than half of the accused teachers who left city schools. Rather than contest their cases, 63 percent of educators brought up on charges during this period accepted settlements, and nearly half of the settlements stipulated that the teacher resign or retire. In addition, 85 teachers left the system without an agreement.

The figures fluctuate, but a DOE spokesman characterized them as “stable over time.”

All told, the city brought charges against 1,550 teachers. Of those, 673 were incompetence cases prosecuted by the DOE’s Teacher Performance Unit, a 14-lawyer office created in 2007 by Bloomberg and his schools chief Joel Klein to target ineffective teachers.

“We have clear policies to ensure great teachers are in every classroom and to move teachers who shouldn’t be teaching out of the system,” said Doug Cohen, a DOE spokesman. “Every year, we use all the tools at our disposal to address any case of employee misconduct or incompetence, and the number of cases closed changes from year to year.”

The teachers

The 74’s sample is too small to support conclusions about the profile of failing teachers, but an overview is suggestive. The 154 teachers who faced firing for either incompetence or misconduct had been teaching in city schools for 18 years on average — seven years longer than the average citywide. As of June, the salary of a New York City teacher with that many years in the classroom and a master’s degree is $96,632.

Males were overrepresented, making up 42 percent of the sample, though they comprise 23 percent of all city teachers. Additionally, nearly half of the misconduct sample were men, as were most of those fired for it (13 of 23).

“There are differences between the men and women who go into the teaching field,” said Charol Shakeshaft, a professor of educational leadership at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, who has tracked national trends in teacher misconduct. She said women remain more likely than men to see teaching as a first choice.

“On average, women are better prepared or more psychologically prepared, which may make them less likely to lose their patience and act out against a kid,” she said.

Serious infractions by teachers are rare, but the cases — 74 alleging misconduct and 80 alleging incompetence — offer a fascinating, unsettling, sometimes tragic view into school life.

Case decisions sometimes read like novellas but written by lawyers. They described classrooms where teachers admonished students with physical force or racial and homophobic slurs, skipped class to play games on their phones and talk to their friends, and left uncompleted — or forged — forms needed by students with disabilities.

Poor attendance was a common problem, never more so than in the case of a veteran secretary at a small Bedford-Stuyvesant school, who missed at least part of 156 school days out of 180 in the 2011-12 school year and 118 in 2013-14. In Harlem, a former middle school teacher went into a tailspin after taking on a K-1 bridge class: she stopped planning lessons and grading work, stopped answering her mail, and was absent for weeks at a time.

“You get really egregious behavior because the steps to be taken for dismissal are just so lengthy, so expensive, and so rarely successful that most principals are reluctant to even initiate the process,” said Patrick McGuinn, a professor of political science and education at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey.

“The challenge and problem is that before they had tenure and due process, teachers were treated badly in terms of hiring, firing, sexism, racism — you name it.”

A Vietnam veteran teaching art in Williamsbridge put his hands around a student’s neck and threatened to snap it. A teacher who had spent several years in the Absent Teacher Reserve, the city’s pool of educators who have lost permanent positions, made threats about stabbing an assistant principal and warned another supervisor that he planned to “sit shiva” for her, referring to the Jewish practice of mourning the dead.

In what appeared to be a non sequitur, the arbitrator, in ruling for termination, described the teacher, who had a history of verbal abuse, as “formerly a musician and a writer.”

Anger coursed through the decisions. A Brooklyn instructor with more than two decades of experience was sent to the ATR after her school discontinued its technology department. When assigned to a K-8 in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn, she refused to report, insisting she’d had a “traumatic experience” at the school.

“Well if I go in there with a f**king gun and shoot up everyone there, then what are you going to do?” the teacher said. “I am not going back to that f**king school.” An arbitrator ruled in 2015 that the threat merited firing irrespective of whether the teacher intended to carry it out.

More often, arbitrators looked to punish even serious first infractions less severely than second ones, and second less than third. That practice may have saved the job of a French teacher at Francis Lewis High School in Queens who said to a female student, “I’m going to tell your boyfriend to break up with you,” and touched the student’s stomach through her clothes.

The teacher lied repeatedly in his testimony and showed no remorse, the arbitrator found.

“I find some basis for mitigation, however, in Respondent’s relatively long-term employment and clean record since joining the Department in 2002,” she wrote in her 2016 decision, suspending him for six weeks and requiring courses on “appropriate student/teacher boundaries.”

Calibrating a punishment to fit the offense was not clear-cut in many cases, especially when conflicts played out on the murky terrain of failing schools. Supporters of existing tenure protections say teachers, particularly when outspoken, can be targeted by principals.

“It is not in students’ interests for teachers to be at-will employees, or for teachers to be fired without evidence,” said Dick Riley, a spokesman for the United Federation of Teachers, the New York City teachers union. “While nobody disputes that teachers should have to prove their competence — tenure is earned, not bestowed — once they have, tenure means they cannot be fired for things like teaching uncomfortable subjects, speaking up on behalf of students, or refusing to change grades.”

In perhaps the most straightforward and disturbing case, a Brooklyn English Language Arts teacher repeatedly met a 12-year-old student in her home or a motel near the school and had sex with him, sometimes intoxicating him first. Acquitted on criminal charges, she blamed the student for “manipulating” her and fought her termination in state Supreme Court, where the arbitrator’s decision was affirmed by an appellate judge.

Not all the cases involved students. Teachers were fired for falsifying expense forms and doctor’s notes, tax fraud, and repeated shoplifting. The latter case involved a Bronx elementary school teacher and serial thief whom life appeared to have gotten the better of.

Already banned from the Lord & Taylor in suburban Eastchester, she stole hundreds of dollars of merchandise from Bloomingdale’s and Nordstrom’s while paying for additional merchandise with a credit card she swiped from a school paraprofessional. She pleaded guilty to most of these charges but refused to acknowledge stealing a box of tampons from a Rite-Aid even though she was caught.

“I am deeply moved by the tragic circumstances described by the Respondent,” the arbitrator wrote, referring to “three traumas” that were not described in the decision. “However, I cannot find those factors sufficient to mitigate the severity of Respondent’s misconduct.”

Termination in New York City does not result automatically in revocation of a state teaching certificate, and most of the fired teachers retained their license. A criminal conviction is likely to trigger state action, however, and the shoplifting teacher is one of four brought up on misconduct charges whose records were obtained by The 74 who lost their license.

The schools

No teachers from New York City’s specialized schools faced charges in The 74’s sample, although the elite institutions have been the site of widely publicized cases in the past. Nor were teachers from any of the 20 most popular city high schools charged.

Each of the 32 community school districts were represented, as was District 75, which provides specialized settings across the city for students with severe disabilities. The DOE tried to fire only one teacher in Staten Island schools, which enroll about 7 percent of New York City’s roughly 1 million students.

By contrast, 41 educators taught in the Bronx, where roughly one-fifth of city students go to school. Nineteen teachers worked in three Bronx districts where at least 89 percent of the students are poor — compared with 74 percent citywide — and which enroll some of the largest chronically absent and homeless populations. Black and Hispanic students comprised 96 percent of the school population in these districts, versus roughly 70 percent citywide.

Accused teachers taught all grade levels and required subjects. Twelve worked in foundering schools unpopular with students and families that later closed. These included Jane Addams High School in the Bronx, one of a handful of schools where the principal trying to fire a teacher was herself being investigated and would be forced to resign on unrelated charges. (Adding insult to injury, the arbitrator misspelled the name of the school throughout the decision.)

Another 17 teachers were charged while working at schools flagged as low-performing by the state, and 10 more charged with incompetence taught at schools that would be assigned to Mayor de Blasio’s Renewal program, which provided nearly $600 million in extra resources for school turnaround but has made little difference, critics say.

The hearings

The decisions handed down in 2015 and 2016 addressed behavior occurring between 2011 and 2014. Critics have long argued that the 3020a process — named after the state law enumerating tenure protections — is unnecessarily slow and expensive, giving principals incentive to offload ineffective teachers to other schools rather than try to discharge them.

Between 2005 and 2008, according to a survey of district leaders by the New York State School Boards Association, the average disciplinary case lasted 502 days after charges were filed and cost districts an average of $216,588.

“We lobbied very strongly for changes in the law that would ensure our employees of the due process they’re entitled to but would be expedited so that districts wouldn’t have to make economic decisions about who to retain,” Jay Worona, the school board association’s deputy executive director and general counsel, told The 74.

Worona pointed to reforms that have shortened the deadlines for submitting evidence and choosing arbitrators. When the association surveyed districts again this year, it found that hearings were concluded in 180 days and cost $141,772. New York City, which prosecutes the lion’s share of hearings in the state, did not participate in either survey, however.

Those who found fault in the past argue that firing a tenured teacher remains cumbersome and slow, especially in incompetence cases, which usually require extensive documentation over two or three years of observations, conferences, and improvement plans.

Kathleen Elvin became the bete noire of the teachers union after charging several teachers with incompetence at John Dewey High School, a storied Brooklyn institution that was slated to close when she arrived in 2012.

Now assigned to an administrative office in Brooklyn, she spoke to The 74 about what’s involved in dealing with persistently struggling teachers — from efforts to help them improve to bringing a case against those who don’t get better.

“If you’re doing it right,” she said, “if you’re being just and fair and ethical, it could take you 100 hours easily.”

Disclosure: David Cantor served as the Department of Education’s press secretary under Mayor Michael Bloomberg from 2005 to 2010.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)