Investigation: Hefty Fines, Long Suspensions, but Rarely Losing Your State License: Documents Show What Happens to NYC Teachers After They’re Disciplined

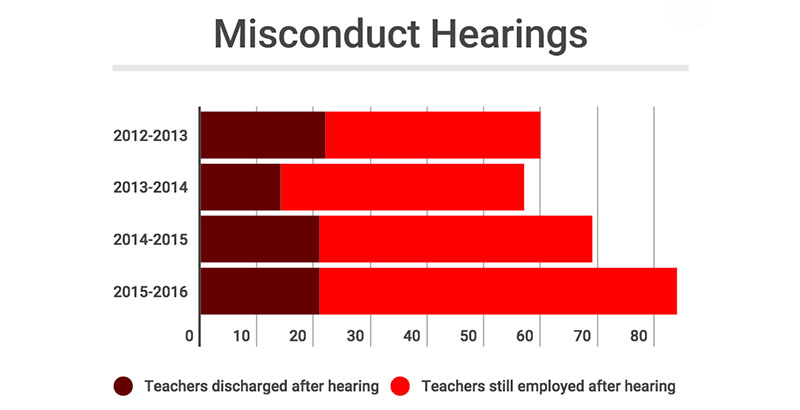

New York City’s effort to remove abusive or incompetent public school educators led to more than 700 terminations, retirements, resignations, and voluntary departures during four school years between 2012 and 2016, disciplinary records provided by the city’s Department of Education show.

Arbitrators who ruled on the charges brought by DOE lawyers during this period sided with the city in dismissing 188 employees, nearly all of them teachers. Another 469 staff members in schools across all five boroughs elected not to argue their cases at a hearing, agreeing instead to settlements stipulating that they resign or retire. Eighty-five others exited the system without a settlement.

Nearly 800 more who were also charged with misconduct or incompetence remained in the school system but were fined or suspended, either through a settlement with the city or when an arbitrator stopped short of firing them after a hearing.

In August, 28 months after a records request under the state’s Freedom of Information Law, The 74 obtained decisions handed down by arbitrators in 154 disciplinary cases between January 2015 and April 2016.

Seventy-five educators in the sample were fired, 52 of them for incompetence. The DOE shields the identities of teachers whom it deems inadequate, citing state law, but the names of teachers prosecuted for misconduct are public. Several of the 23 fired for behavior that ranged from physical and verbal abuse of students to striking a supervising psychologist did not accept an arbitrator’s ruling as the last word on their career.

Some took their fight to court. A few made it back into the classroom. Nearly all kept their state teaching certificates.

The allegations that faced teachers who avoided dismissal sometimes appeared serious: a middle school English teacher “repeatedly” hugged and commented on the appearance of female students, saying, “Your breasts are staring at me.” But the charges could also be apparently minor, such as bursting into a principal’s office. Like those who were fired, however, few if any of those educators who stayed in the system returned to their old posts.

All but a handful were fined or suspended, and many were ordered by arbitrators to undergo behavioral or professional training, usually at the city’s expense, as a condition of resuming their career.

Most were sent by the DOE from their hearings to the Absent Teacher Reserve, a pool for educators with no permanent position who can be hired by schools, either permanently or as a long-term substitute.

This movement of teachers back into or out of city schools after termination hearings is a constant at the fringes of New York City’s 58,000-member tenured workforce. It happens more frequently at schools with poorer students, and it trains a light on the professional lives of teachers after they become the subject of a DOE disciplinary action.

Life after termination

Many of the teachers whose misconduct cost them their jobs seemed to disappear. Their names sometimes turn up only on sites that charge for searches or in LinkedIn profiles that give the impression they still work for the DOE. An English teacher fired in April 2015 for verbally abusing students and accruing more than 60 absences over two years doesn’t list a specific school but suggests she is currently employed by the DOE — while also seeming to shop her classroom skills.

The Harlem math teacher who hit the supervising psychologist, saying, amid a string of obscenities, “I will f**k you up,” was also absent or late dozens of times. She too gives the impression she still works in a city classroom.

A few are more transparent about their current employment. One teacher who punched and ridiculed her early-grade students became a line cook at a two-star East Village restaurant, according to the networking site Culinary Agents.

At least six teachers fought for years to overturn their termination in New York courts. Some had been found by arbitrators to have committed egregious offenses: Claudia Tillery, a Brooklyn teacher, had sex repeatedly, perhaps for years, with a middle school student. A technology instructor in the ATR named Veronica Telemaque threatened to “shoot up everyone” if she were assigned to a particular school where she said she had a traumatic experience.

Judges ruled in favor of a teacher only once, describing the discharge of a Lower East Side math teacher, for conducting an improper relationship with a student, as “arbitrary and capricious.” Although cleared, the teacher accepted a job as a math teacher at a Brooklyn charter school rather than rejoin the district.

A former junior high school instructor in Brooklyn failed to convince a court she deserved reinstatement after directing homophobic slurs at students and calling one a “n****r f**ker,” but was able to gain a math position at a different Brooklyn charter.

A DOE spokesman said city charters have “completely separate hiring guidelines.” But state officials concurred with James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center, who said that charters “are required to do whatever district schools do” in vetting potential new teachers, including fingerprinting and criminal background checks. Charters do not have access to DOE employee records, however.

An official said the city cooperates when contacted by other systems. “We work to confirm employment info about previous employees pursuing employment in other districts, within the law,” he said.

Losing your job but not your license

Although terminated teachers cannot return to city classrooms, 18 of the 23 discharged for misconduct in The 74’s sample retained their state teaching certificate.

“Certification and discipline are sort of separate issues,” said Jeanne Beattie, a spokeswoman for the New York State Education Department, which oversees teacher licensing. As in many states, “termination doesn’t have a direct implication for a teaching certificate.”

Disciplinary hearings, which must be reported to the state Education Department, are among the possible triggers of an investigation into whether an educator lacks the “moral character” to remain credentialed.

State officials received an average of 6,100 complaints for each of the years between 2015 and 2017 — including reports from law enforcement and districts, some of which may concern the same incident — and revoked the certificates of 267 teachers

Many retain their licenses for years after they are terminated, or, even, as with one educator in the sample, after he died.

“It’s just like with a physician,” said Phillip S. Rogers, executive director of the National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification. “They may lose their right to practice at a specific hospital, and it may evolve into a loss of the right to practice anywhere — or it may not.”

Rogers says it’s typical for localities to control employment issues like misconduct while states handle certification decisions. Reports have shown that retaining a license makes it easier for abusive teachers to find new jobs. While he could not rule out the possibility that New York City hired a teacher who had been terminated elsewhere, DOE spokesman Doug Cohen said, “We are not aware of any specific example” of that happening in New York City, where 6,000 new teachers are brought on every year.

Suspensions and fines

For teachers whose behavior did not merit termination, in the view of arbitrators, the road to reinstatement nearly always ran through suspensions or financial penalties. Of 79 teachers in the sample who kept their jobs, 56 were fined, 17 were suspended, three received reprimands, one was demoted for a year to assistant principal, and another principal received an unspecified penalty. One teacher was exonerated.

The numbers are too small to draw conclusions from, but teachers accused of misconduct were far more likely to be penalized financially. Thirty-nine were fined, compared with 17 of those accused of incompetence. The penalties averaged nearly $4,500; the smallest was $250, for repeated lateness to an ATR assignment center (the unassigned teacher became prompt upon learning she was up for a position, the decision noted). A struggling early-grade teacher whose Manhattan elementary school — itself struggling — did little to help her improve was fined three days’ pay.

By comparison, a well-regarded English instructor in central Queens who changed the way a question was scored on a Regents exam was fined $15,000. He kept his job because he made the change openly and reported it himself, believing the official scorer to be in error.

An insubordinate and habitually absent physical education instructor received a $10,000 fine, as did two other PE teachers: one who refused to take down vulgar images of women lifting weights from his classroom wall, the other a volatile, profane former basketball coach who incongruously shouted “I am not a lost Jew” at the assistant principal — supposedly in reference to a remark from years before.

Fines collected from teachers amount to roughly $600,000 annually, according to the DOE, and are used “to offset general expenses” in the district’s more than $25 billion annual budget.

The cost of fines to individual teachers paled in comparison to lost wages for many of the 17 faculty who were suspended. Ten suspensions were for two months or longer, with seven punishing educators charged with insubordination and neglect in addition to incompetence. The longest suspension — “not less than” nine months — went to a 30-year veteran and former school dean who blamed 10 unsatisfactory evaluations over two years on a new principal.

Along with financial penalties, most were required to undergo training in classroom management and instruction, therapy, or anger management — remediation that “in almost all cases” is provided by the DOE and cost the agency $37,000 last year, according to an official.

Absent Teacher Reserve a familiar landing spot

Teachers whom the DOE tries to fire are frequently relocated from their schools to the ATR prior to hearings, and then are returned to the pool if they avoid dismissal. Under the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, say sources familiar with its policies, every teacher who survived a hearing was assigned to the ATR. The procedure today is not quite as uniform, according to the DOE.

“Historically, most teachers were not returned to their school,” an official acknowledged. “However, placement is determined on a case-by-case basis. In cases relating to teacher performance and cases of misconduct where students/other staff involved in the case remain at the school, teachers are more likely to be placed in the ATR.”

A 2014 report by the advocacy group TNTP found that 25 percent of those in the ATR pool faced disciplinary charges, and one-third received unsatisfactory evaluations — a figure that would include all or nearly all teachers brought up on incompetence charges who were not fired.

The ATR will cost the city $136 million this year, according to a June analysis by the Citizens Budget Commission, a good-government group that has advocated for placing time limits on how long teachers can remain in the pool. The report said there were 1,202 teachers in the ATR at the start of the 2017-18 school year and 756 remained by April.

Disclosure: David Cantor served as the Department of Education’s press secretary under Mayor Michael Bloomberg from 2005 to 2010.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)