16 Charts that Changed the Way We Thought About America’s Schools This Year

By Kevin Mahnken | December 15, 2020

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing America’s schools into sharper focus through new education research and data. (Get our newest updates delivered straight to your inbox — sign up for The 74 Newsletter)

Never before has the American education system been put under a microscope — sometimes literally — the way it was in 2020.

That’s because COVID-19 illustrated just how much about schools we take for granted. Education research examines all kinds of things that take place inside the walls of schools, from science lessons and gym classes to sick days and suspensions. But experts have never had to think about what might happen if all of it — the hugs, the free breakfasts, the standardized tests, even the buildings themselves — simply went away. This spring, that’s exactly what happened, stranding tens of millions of students in academic limbo even as this sentence was being written.

It was education’s worst year. But as the months crawled by, researchers kept collecting data and putting surveys in the field. They gave us a picture of which kids were most at risk of falling behind, how fast they might catch up with a dose of high-intensity tutoring, and why local leaders were deciding to reopen schools to in-person learning. Beyond the studies looking specifically at the effects of the pandemic, we continued to learn about the ways in which the nation’s 130,000 elementary and secondary schools make an impact on the lives of children.

What follows is an education history, in charts, of a year unlike any other.

Learning Loss: Picture Still Developing

With the prolonged absence of students from their classrooms, the key educational question triggered by the coronavirus has been just how far they would fall behind in their studies. Given the rocky transition to virtual instruction (to say nothing of the millions of families without internet access at home), many feared that months of Zoom sessions would set achievement back irreparably.

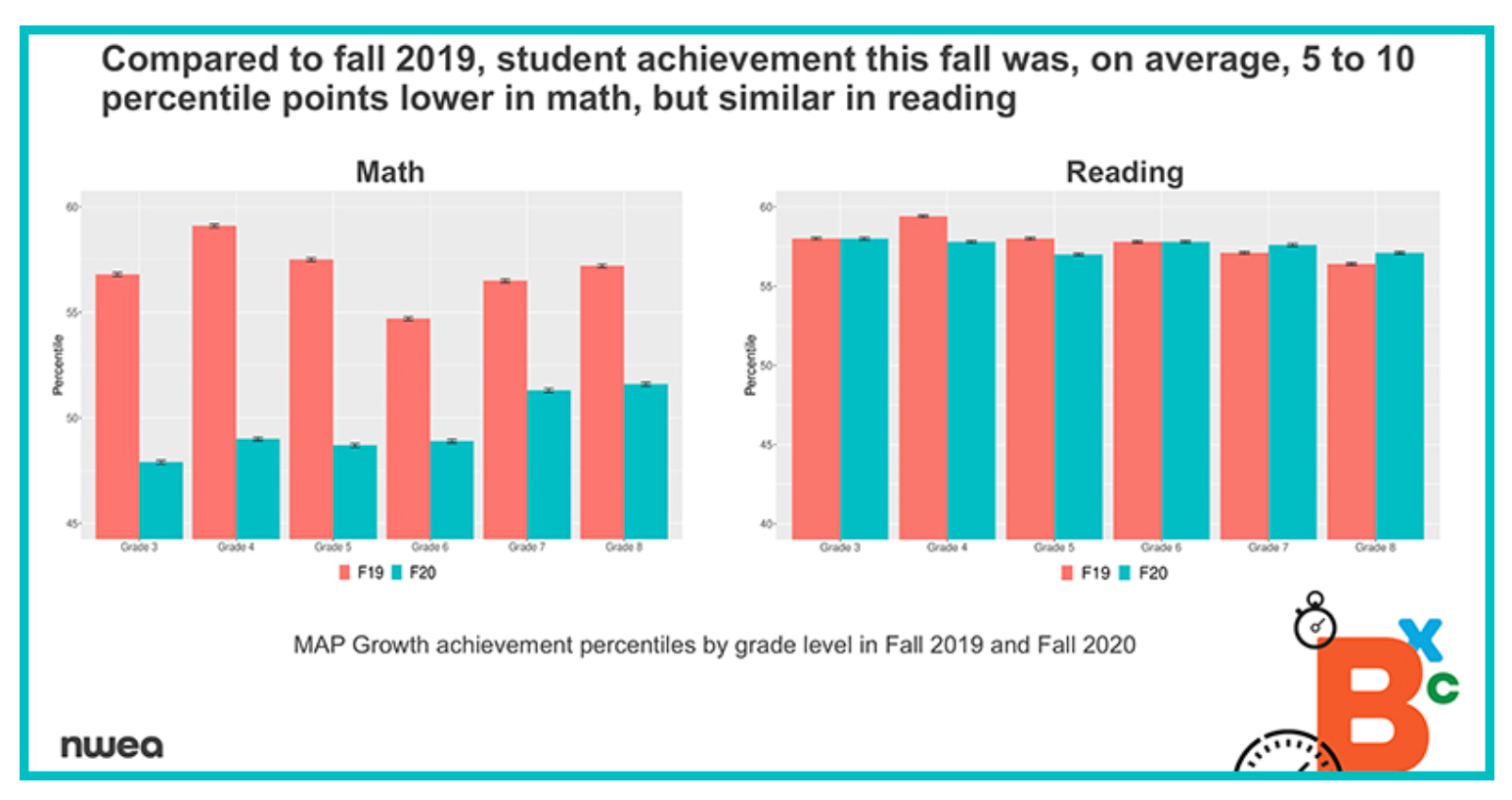

With physical schools in many areas likely to remain closed for months, much is still unclear. But early data suggest that the academic damage may not be as devastating as previously thought. Results from this fall’s MAP test, a computerized assessment devised by the education nonprofit NWEA, show that over 4 million students in grades 3-8 performed somewhat worse in math than their same-grade peers in 2019; their reading skills, however, were little changed. While still preliminary, it’s a better outcome than what the group had predicted in the spring based on research into the problem of “summer slide.”

Still, a major caveat remains: According to NWEA, roughly one-quarter of the MAP participants from last year didn’t actually take the test this fall. And those students, disproportionately Latino and African American, are likely at the greatest risk of being left behind.

Achievement Gaps: Class Matters, in More Ways than One

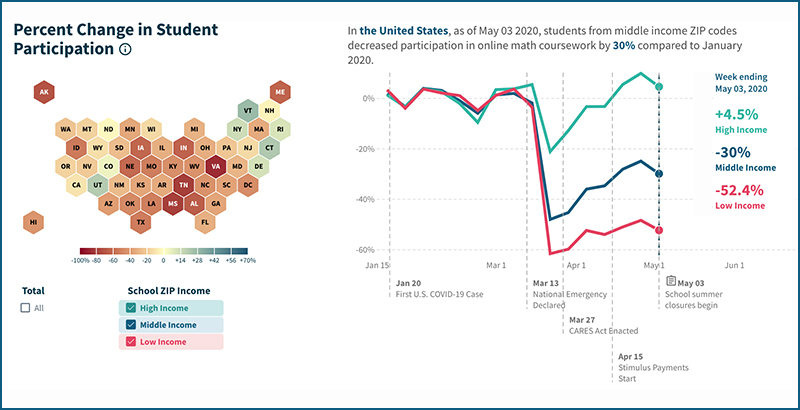

In at least one analysis, some groups of students have already been shown to lag their more advantaged peers. One ongoing research study, conducted by acclaimed economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues at Harvard’s Opportunity Insights, shows that children from lower-income families experienced a precipitous drop in math achievement at the beginning of the pandemic.

The study used data from Zearn, a nonprofit curriculum developer whose online math lessons were used by nearly 1 million students this spring. While schools were able to continue assigning the lessons during the flight from school buildings, kids almost immediately began completing fewer lessons — and those in lower-earning groups fell furthest of all. While the paper focuses mostly on the deadening spell cast by the pandemic over the American economy, the Zearn findings show evidence of its potentially “long-lasting scarring effects,” Chetty and his team wrote.

Tutoring: Can It Be Scaled?

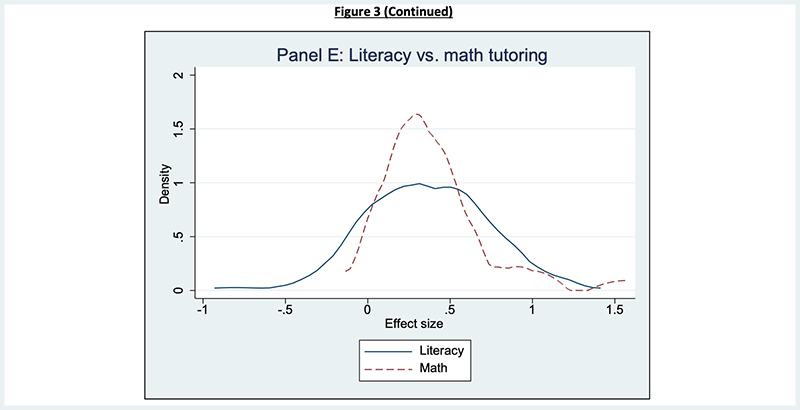

Research on the effectiveness of tutoring has long pointed to a promising method of boosting outcomes for struggling students, but one whose efficacy would be challenging to achieve at scale. To build upon successful models of individual or small-group instruction, you need to hire (or at least train) a lot of new personnel. Whatever the logistical challenges, however, the academic setbacks inflicted by the pandemic over multiple school years have led researchers to give tutoring a closer look in 2020.

In a working paper released this summer, University of Toronto economist Philip Oreopoulos examined evidence from nearly 100 randomized controlled trials of tutoring programs, detecting strongly positive results for academic performance in multiple subjects. Even more promising, the intervention worked — with occasionally eye-popping effect sizes — in multiple formats, even when conducted by tutors who weren’t professional educators. If paraprofessionals, trained volunteers, and even family members can deliver effective one-on-one instruction, there may be potential for the nationwide use of tutors to help students make up ground lost to COVID, as Brown professor Matt Kraft has proposed.

School Reopenings: Politics Trumps Science

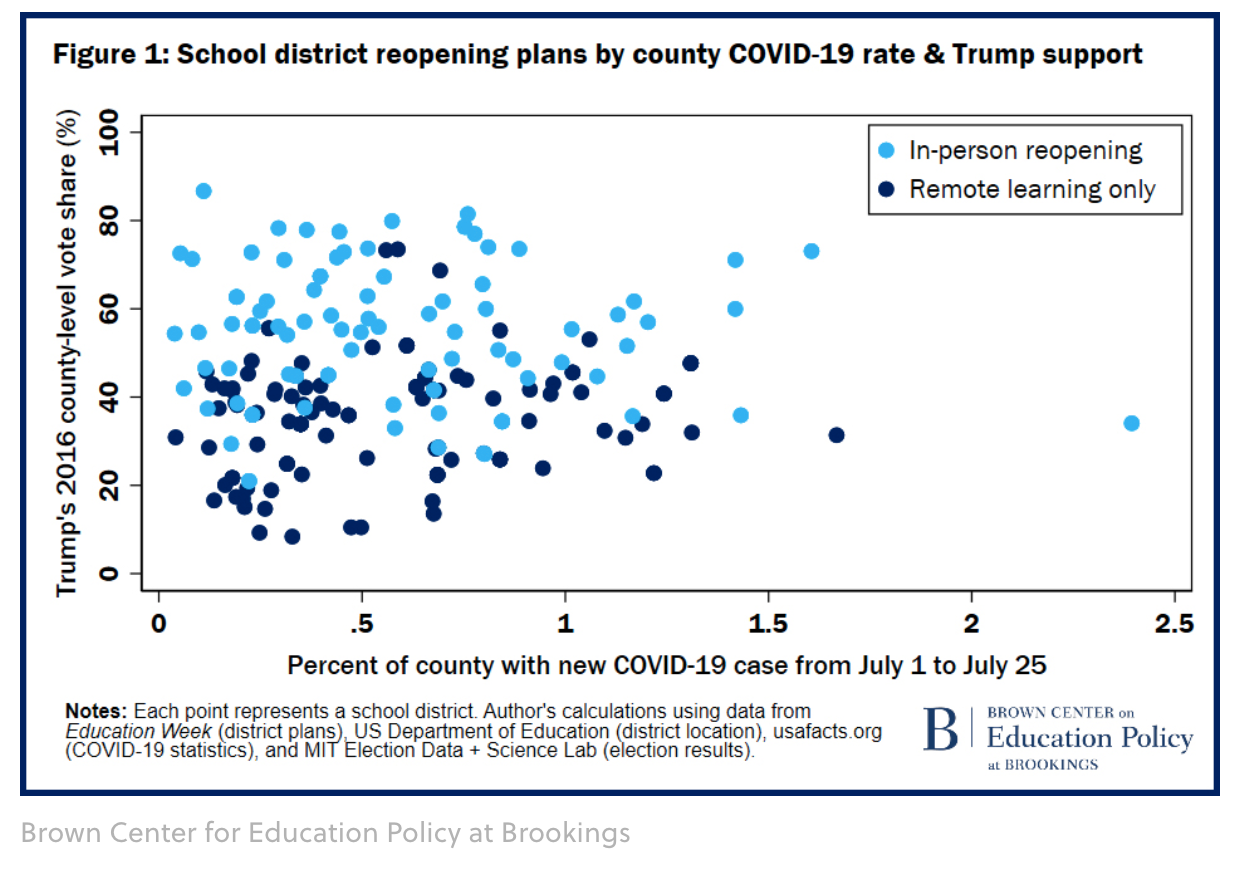

The coronavirus, and the steps undertaken to curb its spread, represented a sudden and almost unforeseeable social challenge. But they also interacted with one of the most familiar forces in American life, partisan politics.

Once Democrats and Republicans began to divide over mask mandates, business restrictions, and hydroxychloroquine, it was easy to predict that school reopenings would trigger a similar reaction. And according to early analyses, that’s precisely what happened. Multiple researchers have found that the county-level development of in-person reopening plans was closely associated with President Trump’s vote share in the 2016 election, but seemingly disconnected from the prevalence of COVID in a given community. As Brookings Institution senior fellow Jon Valant told The 74, “When an issue like this gets charged, it distorts the decision making in ways that are really dangerous.”

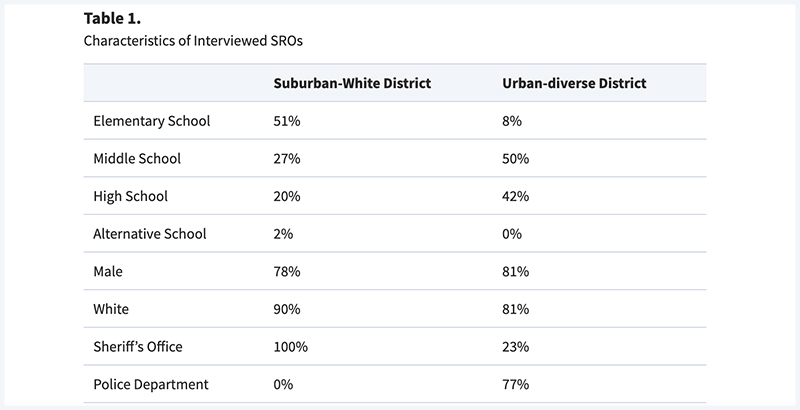

School Safety: How Police See Students

Apart from the pandemic, the other major education storyline of 2020 related to racial inequality. Following the killing of George Floyd in May, districts in major cities like St. Paul, San Francisco, and Seattle all moved to wind down contracts with local police departments, often placed inside school buildings to ensure safety and order. Meanwhile, a qualitative study published in the journal Social Problems offered troubling evidence of how school resource officers view the kids they serve.

Relying on a sample of interviews with over 70 officers across two communities, the authors found that those stationed in racially mixed schools were more likely to view students as behavioral threats than those working in a wealthier and whiter community — even though juvenile arrest rates were broadly similar in both areas. That belief, combined with the common use of what the researchers deemed “racialized tropes,” could lend credence to the calls by activists to remove police from schools.

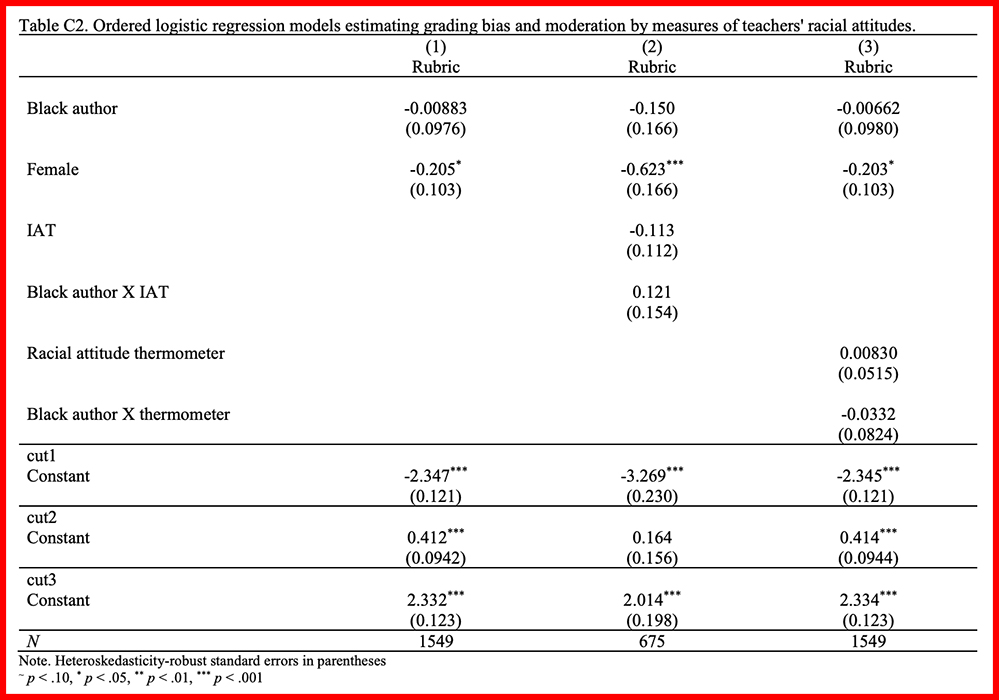

Racial Equity: Rubrics Could Shrink Grading Differences

Even before this year’s outcry over police brutality, education observers have long argued that structural bias built into the K-12 system contributes to racially disparate outcomes for students. The building debate has led many school districts to adopt forms of anti-racism training meant to purge prejudice from school interactions, though the evidentiary basis for its effectiveness is somewhat scant.

In a working paper circulated this summer, however, USC education professor David Quinn examined the effects of another approach to combating bias: standardizing the way teachers evaluate student work. In an experiment soliciting responses from over 1,500 instructors, Quinn found that participants tended to gives lower marks to a writing assignment credited to a student who was hinted to be non-white — through the use of a racially identifiable name such as “Dashawn” — than to an identical assignment credited to a student named “Connor.”

But that tendency was measurably reduced when the teachers were asked to use a grading rubric with performance criteria related to specific aspects of the assignment. In fact, use of the tool shrank the racial differences almost entirely. The “thoughtful selection of evaluation measures,” Quinn wrote, could be a powerful tool in the classroom.

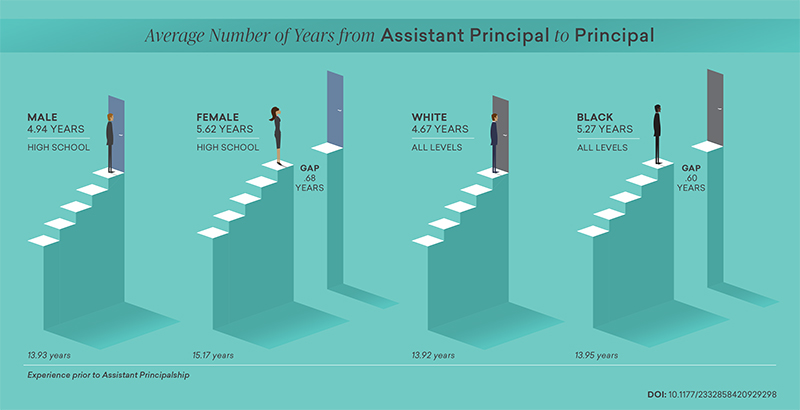

Leadership: Black Principal Candidates At a Disadvantage

For all the talk in recent years about the importance of student-teacher racial matching — study after study points to better outcomes for non-white students, from test scores to disciplinary infractions, when they are taught by at least one teacher who looks like them — the American principal pool is comparably homogenous. One phenomenon feeds the other, as minority leaders often have greater success recruiting and retaining minority teachers.

A study published by the American Education Research Association provides a stark look at the problem. In an analysis of 4,700 assistant principals in Texas between 2001 and 2017, the authors discovered that 45 percent of white candidates were eventually promoted to the top job, while only 35 percent of African American candidates were. The disparity persisted even though candidates of both races possessed master’s degrees and state credentials that qualified them for leadership. Even more striking, the average wait time for a promotion was seven months shorter for white administrators.

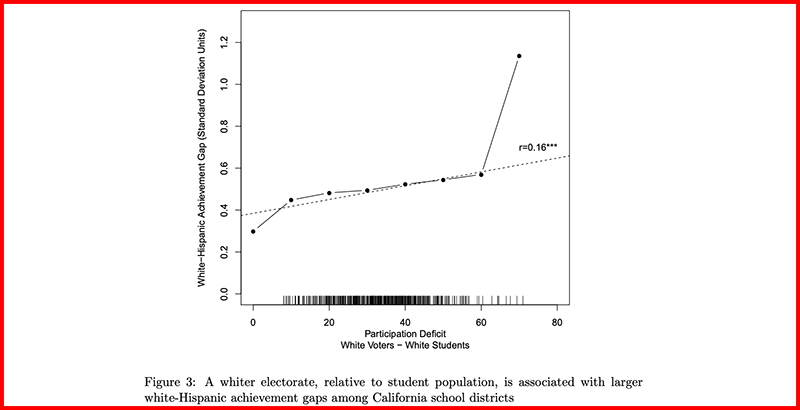

Education Politics: School Boards Skew White

School board elections are almost destined to produce low engagement and even lower turnout, as obscure candidates compete for offices during off-year campaign cycles. The limpness of the democratic process likely explains why research has typically found that local board members are much more likely to be wealthy and white than the people they represent.

A study from the beginning of the year put that point in even finer relief. Ohio State University professors Vladimir Kogan and Stephane Lavertu, together with Emory University professor Zachary Peskowitz, used voter turnout records from board races in California, Illinois, Ohio, and Oklahoma to show that the race of school board members is often totally unrepresentative of not just the adult electorate, but also the student population that they served. In fact, most majority-nonwhite districts elected majority white school boards.

Even worse: As the representation gap grew between the politicians and their constituents, so did the racial achievement gap in schools.

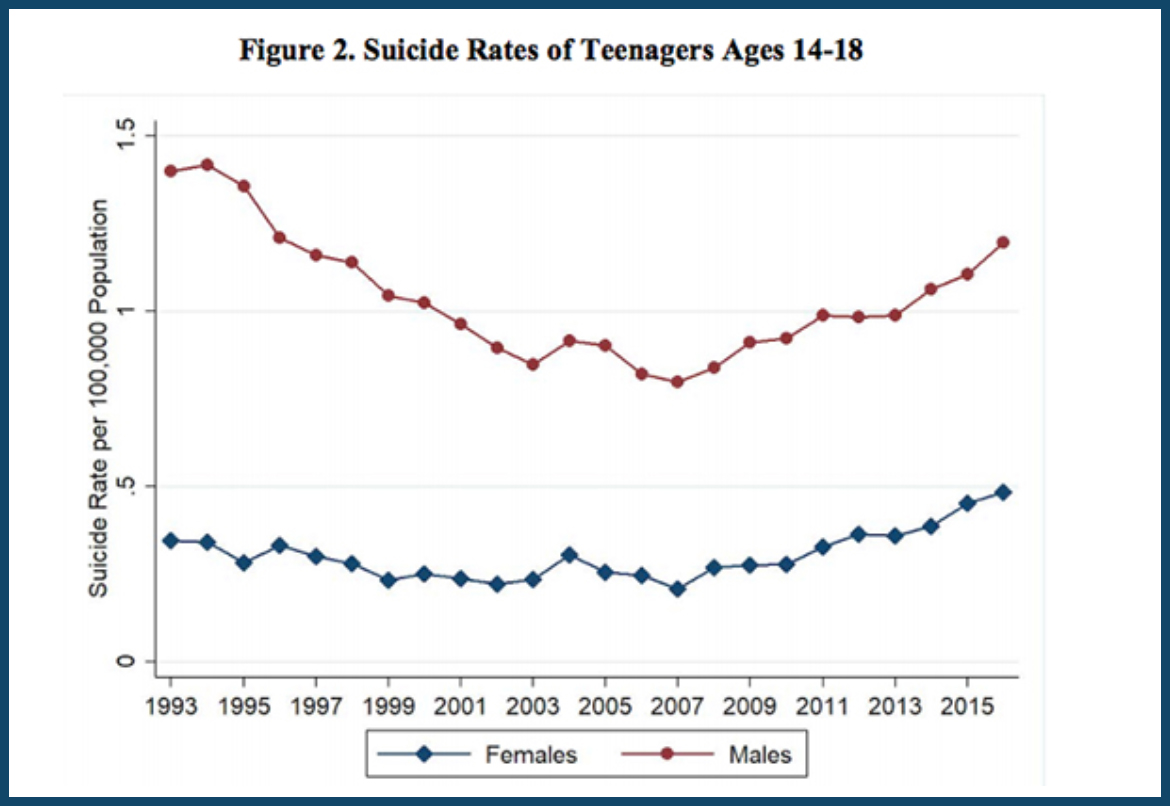

Mental Health: Anti-Bullying Laws Reduce Student Suicide

Surging reports of teen anxiety and depression have focused both educators and families on the issue of student mental health, particularly among adolescents. Underlining the trend has been a frightening increase in the teen suicide rate, often surfacing in the media through tragic accounts of kids driven to despair by bullying at school.

Partially in reaction to the frightening numbers, every state in the country has passed legislation forcing education leaders to combat abusive behavior in schools. In a working paper released in February, researchers point to signs that their efforts have already borne fruit: Among girls between the age of 14 and 18, the adoption of anti-bullying statutes is associated with a decrease in bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation. Suicides dropped by 15 percent, while LGBT girls were 18 percent less likely to plan to commit suicide.

Those results come with an asterisk, however: Boys, who are substantially more likely to commit suicide and less likely to seek emotional support when being bullied, saw no reduction in suicide rates from the laws.

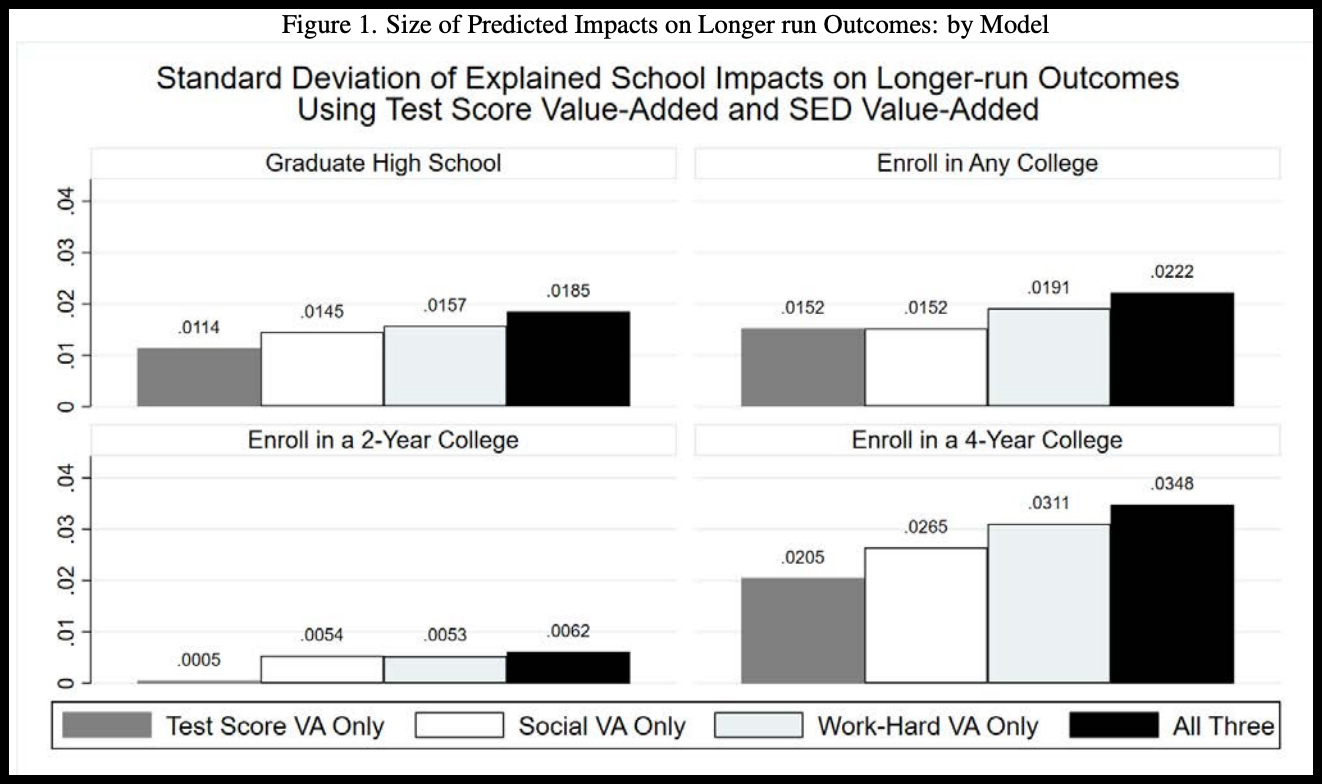

Beyond Test Scores: Social-Emotional Learning in High Schools

Social-emotional learning represents perhaps the hottest field of education research heading into 2021. Beyond the traditional knowledge and skills that students need to gain from school, scholars have increasingly argued in recent years that young people must be invested with non-academic traits to succeed as adults — patience, flexibility, gratitude, and most famously, grit.

That kind of personal development has often been the focus of kindergarten and elementary schools, but recent evidence indicates that it can be accomplished with meaningful results in the higher grades as well. Using data from both standardized tests and school climate surveys, a group of researchers compared the performance of students who attended public schools in Chicago. Their main finding: For a range of outcomes including absenteeism, school-based arrest, high school graduation, and college enrollment, students were actually better off attending high schools that were shown to inculcate social-emotional traits rather than those that maximized test score growth.

Even within the group of non-academic indicators, noteworthy differences surfaced. According to student survey responses, certain schools excelled particularly in building strong work habits and academic engagement, while others were better at fostering a sense of social belonging. In each case, however, the findings show that the social-emotional progress of older students makes a clear difference in how their lives unfold.

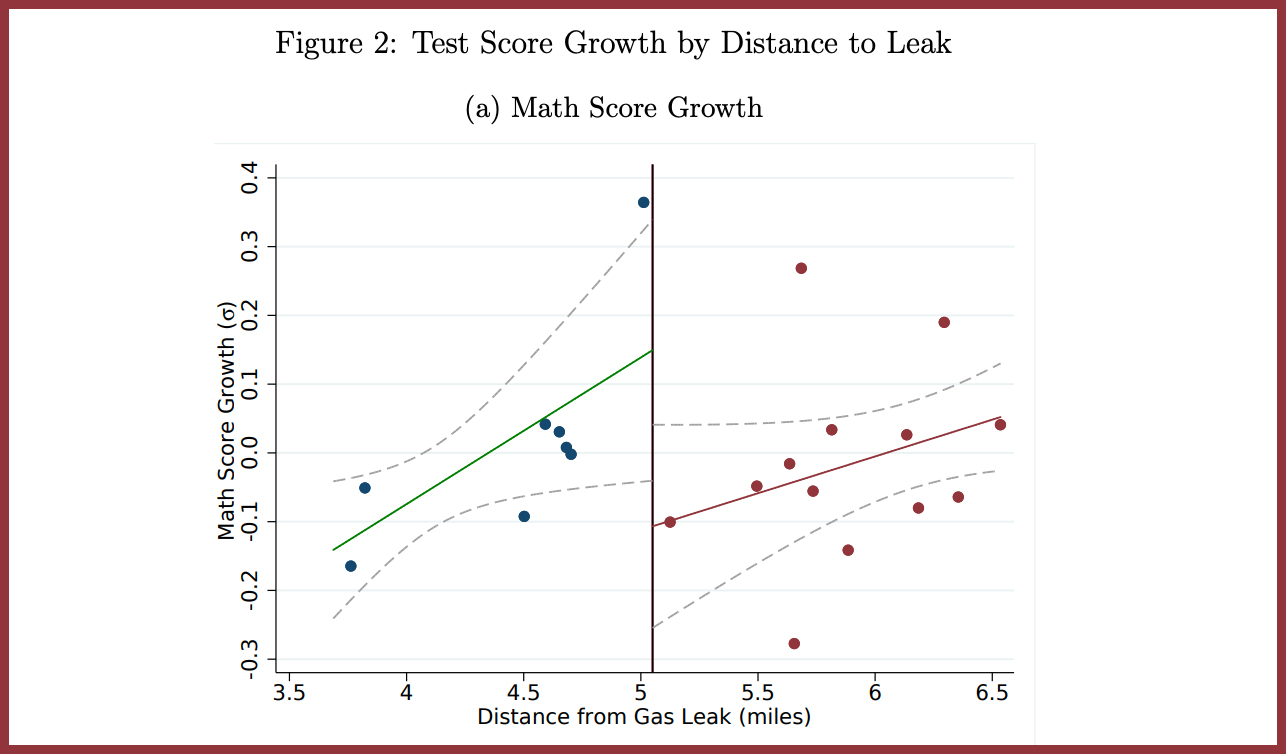

School Environment: Air Quality Makes a Difference

Environmental contaminants are a hidden danger in K-12 schools. Long before the coronavirus outbreak made parents afraid to send their kids to school, polluted drinking water and forgotten asbestos threatened to poison students in the places they should have been safest.

A raft of studies has emerged in recent years providing evidence of the damage wrought by polluted learning environments, including a January working paper documenting the aftereffects of a pervasive 2015 gas leak in Southern California. After some local schools installed commercial air filters in classrooms to deal with the problem, NYU economist Michael Gilraine found significant increases in student test scores for both math and English. The size of the effects — roughly comparable to previous gains attributed to lowering class sizes by one-third — is particularly notable given the small scope of the intervention: essentially, the purchase of a $700 filter.

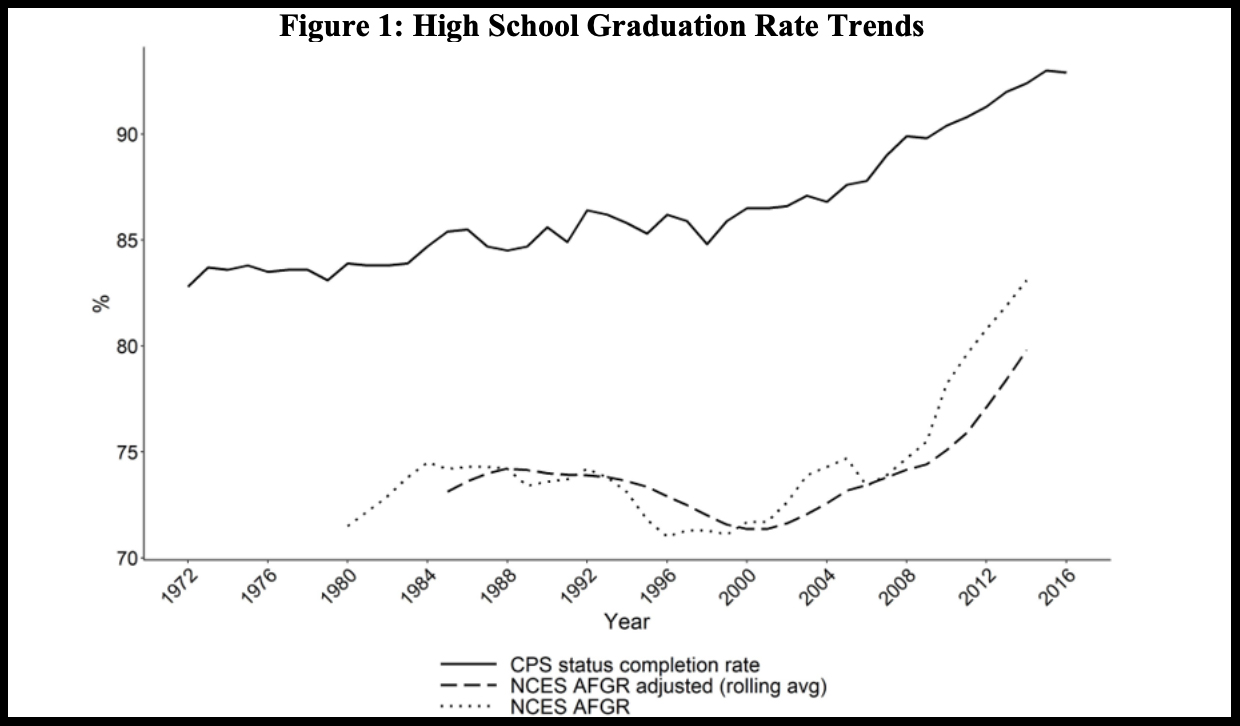

Accountability: NCLB Helped Lift Graduation Rate

Perhaps the most controversial statute in the history of federal education policy, the No Child Left Behind Act was defanged five years ago after lawmakers of both parties tired of its incursions on state authority. Few mourned the law’s death at the time, but a March paper from Brookings Institution found that it likely played a part in one of the happiest K-12 developments in recent decades, America’s steadily rising high school graduation rate.

The report found that the nationwide trend toward greater high school completion was spurred to a significant extent by NCLB’s accountability mandates, which pressed states to identify schools and districts with low graduation rates and make a concerted effort to raise them. Better still, the authors argued that the progress could not be credited to what it deemed “strategic behavior,” such as sticking struggling students in ineffective credit recovery courses. “The more we dug into it, the more it actually seemed like pretty good news,” said Tulane researcher Doug Harris. “And I think that it’s big news.”

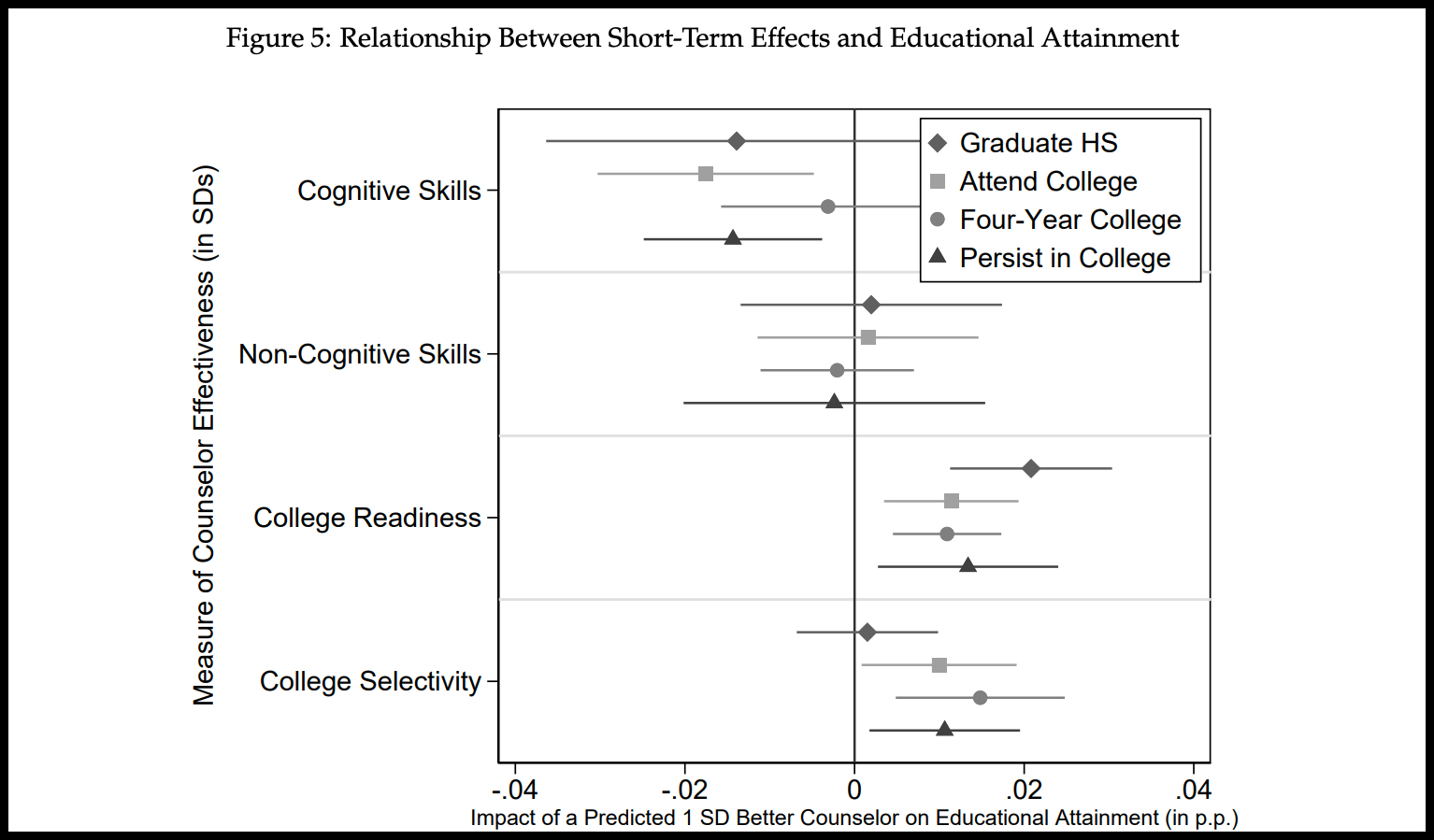

School Workforce: Kids Need Counselors

When examining how schools impact the lives of students, researchers understandably focus on teachers. They run the classroom, devise curricula, grade homework, address misbehavior, make home visits, and perform a dozen other small pedagogical actions each day. The study of school quality is, to a great degree, a study of teacher quality.

But they’re not the only adults in the building, and this year brought clear evidence about the importance of non-teaching staff. Specifically, a study conducted by RAND Corporation researcher Christine Mulhern looked at 510 guidance counselors randomly assigned to high school students in Massachusetts, concluding that their effects on academic attainment were “similar in magnitude” to those of teachers. By focusing on course scheduling, personal support, and college and career advising, Mulhern found, high-quality counselors make a significant impact on kids approaching adulthood — particularly low-income and poorly performing students who most need their help.

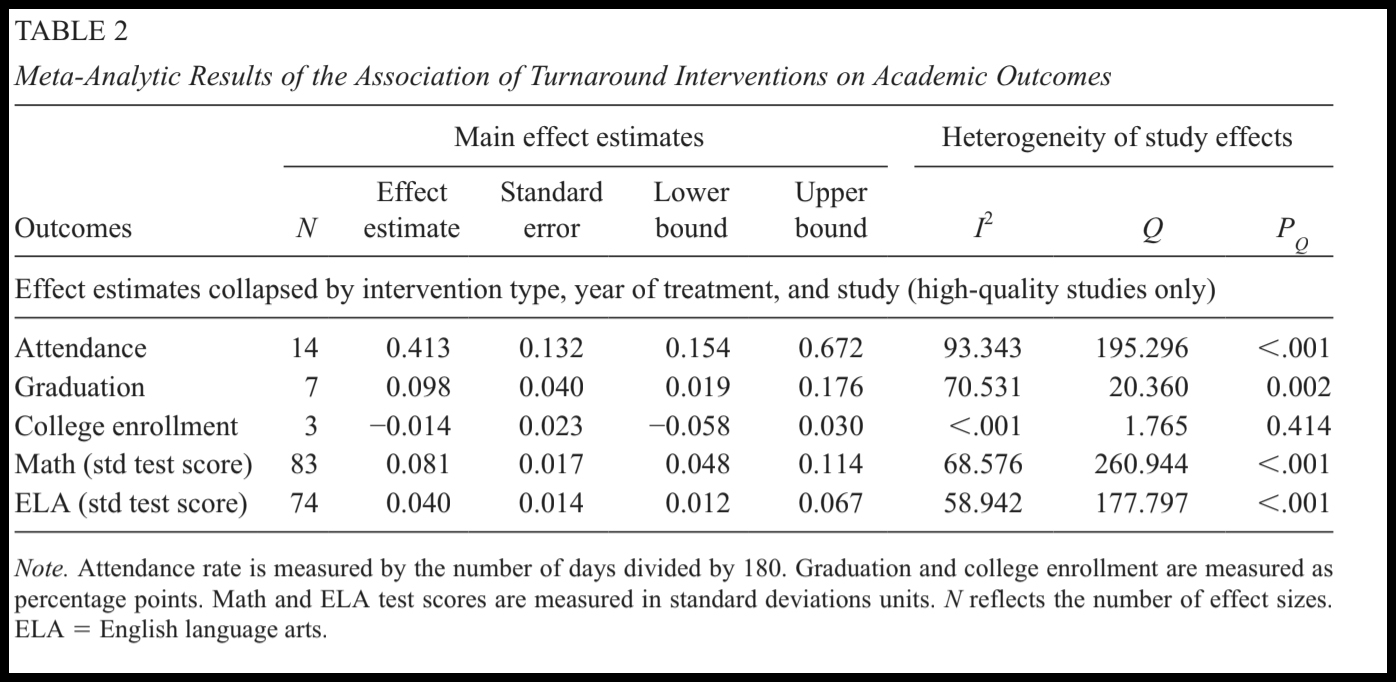

School Turnarounds: Worth a Second Look?

It’s tough, and possibly cost-prohibitive, to turn around schools. That’s the verdict rendered by mammoth research studies and frustrating public policy alike, as district and state leaders have tried to improve school performance through new leadership, new teachers, and big changes to culture and academic programming. The intense shakeup for families and teachers — which typically includes large numbers of staff members losing their jobs — can effectively sabotage intended improvements.

But a September study gives reason to think that turnarounds work better than we thought. In a metaanalysis of 35 studies that looked at school turnaround efforts, University of Florida professor Christopher Redding and Kansas State University professor Tuan Nguyen found consistent and wide-ranging benefits to schools from wiping the slate clean. High school graduation rates at turnaround schools rose by nearly 10 percentage points, along with smaller gains for student attendance and test scores for both math and reading.

The authors also warn policymakers to be patient while waiting for the fruits of a highly disruptive reform; while leaders of turnaround efforts are often judged almost immediately on the effects of their new methods and personnel, meaningful academic gains sometimes don’t show themselves for several years.

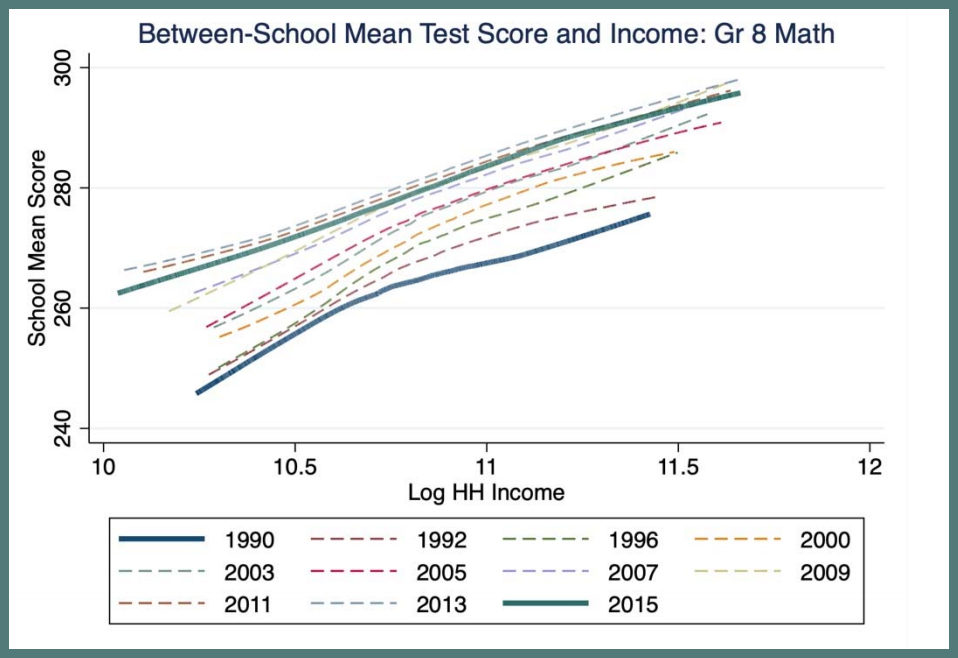

Socioeconomic Stratification: Long-Term Gaps May Be Closing

Few developments have marked the last half-century of American history like the persistent growth of income and wealth inequality. Economists have offered myriad explanations for the divergence in fortunes between educated, often-white professionals and lower-earning members of the working class, and the trend has shown no signs of abatement during the chaotic COVID slowdown.

Happily, however, stratifications in socioeconomic status may not be replicated in academic achievement. In one of the most unexpected social science discoveries of the year, a group of Harvard and Dartmouth researchers found that test score gaps associated with household income shrank over multiple rounds of the National Assessment of Educational Progress between 1990 and 2015. Differences on fourth-grade math, fourth-grade reading, and eighth-grade math all “narrowed substantially,” the authors wrote, while the eighth-grade reading gap remained unchanged.

The paper’s conclusions differ dramatically from those of Stanford academic Sean Reardon, the nation’s most influential scholar of socioeconomic achievement gaps, who has pointed to evidence suggesting the opposite. If they prove accurate, however, they could provide the best news that schools have seen in…well, about a half-century.

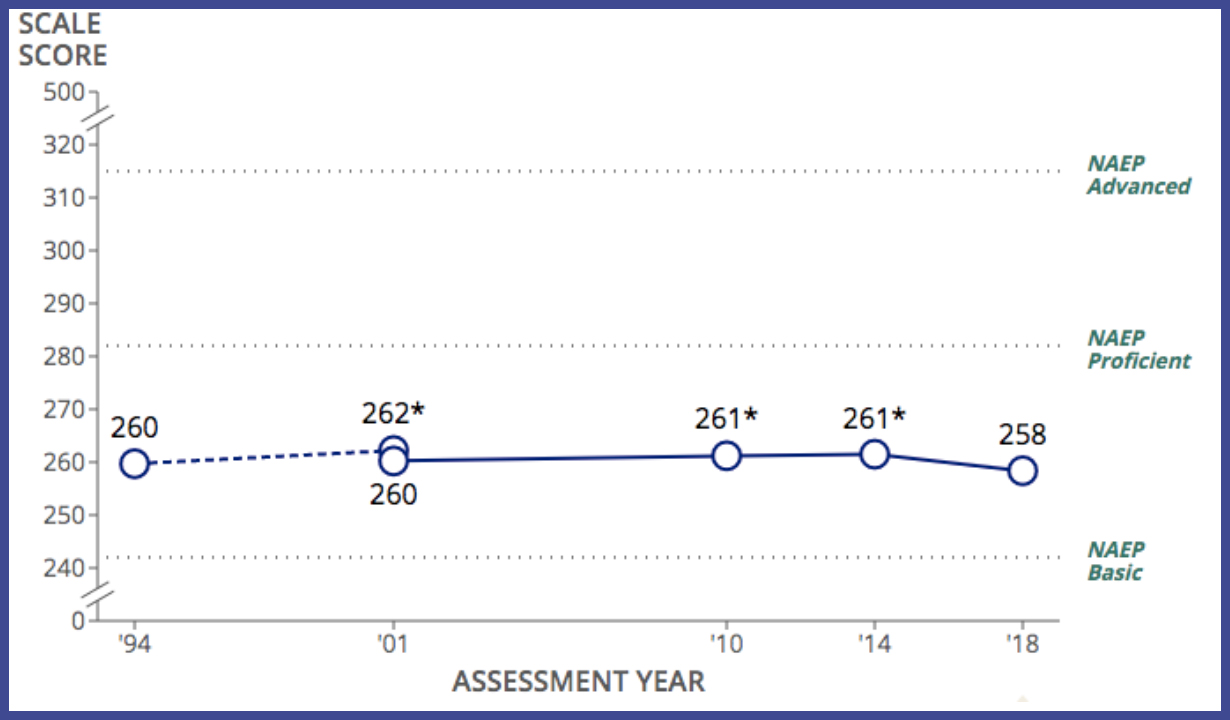

NAEP: More Results, More Disappointment

The National Assessment of Educational Progress has been a chronicle of gloom for well over a decade. After measuring steadily rising scores during the late 1990s and early ‘00s, the exam — commonly referred to as the Nation’s Report Card, but you knew that already — has largely shown stagnation for American fourth- and eighth-graders on both math and reading. Culprits for what has been dubbed the “lost decade” of educational progress are multiple and varied, but analysts have often converged on the harmful effects of the Great Recession, which dislocated millions of families and forced lawmakers to slash school budgets.

This year’s release of 2018 NAEP scores for civics, geography, and U.S. history offer no reprieve from the bad news: Eighth-graders posted lower on the seldom-tested subjects (the assessment is only given every four years, while the core test of math and reading occurs every two) than they did in 2014. A predictable wailing ensured, with Education Secretary Betsy DeVos lamenting that the middle schoolers “don’t know what the Lincoln-Douglas debates were about, nor can they discuss the significance of the Bill of Rights, or point out basic locations on a map.”

Dissenting voices — including some from historians and civics education specialists — tempered the despair by noting that the 2018 declines weren’t particularly dramatic, and that NAEP’s bar for proficiency is considerably higher than those for state exams. But the context for release made its findings even less welcome: In order to save on future assessment costs, geography isn’t scheduled to be tested again until 2029.

Go Deeper: Find our latest coverage of education research and data in our ‘Big Picture’ archive (Get our newest updates delivered straight to your inbox — sign up for The 74 Newsletter)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter