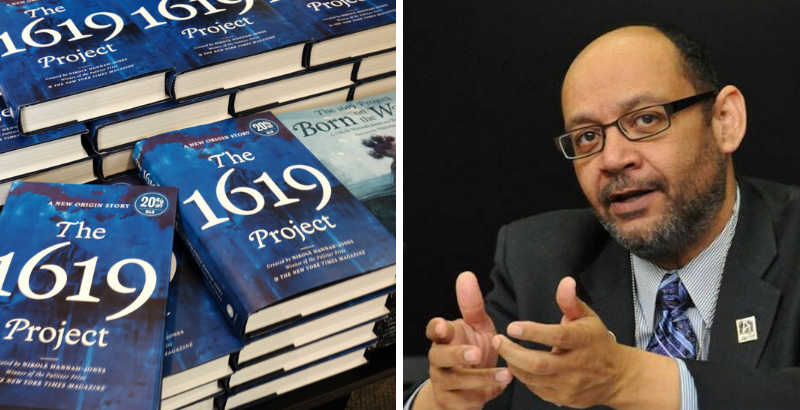

The 74 Interview: Howard Historian Daryl Scott on ‘Grievance History,’ the 1619 Project and the ‘Possibility that We Rend Ourselves on the Question of Race’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

See previous 74 Interviews: Andrew Rotherham on the Virginia governor’s race, researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings on culturally relevant teaching, and author Bonnie Kerrigan Snyder on free speech and Critical Race Theory. The full archive is here.

Over the last two years, a dispute over history has been waged in classrooms, school board meetings, and statehouses. It has drifted in and out of the spotlight as the 2020 election and the COVID-19 pandemic have dragged on, but the question at the heart of the controversy persistently hangs over the discourse around K-12 education: Who gets to decide what students learn about the nation’s past, especially when it addresses the topic of race?

Daryl Scott doesn’t hesitate to call the conflict a “war” — a culture war begun long before the emergence of the 1619 Project or the sudden ubiquity of the term Critical Race Theory. A professor of history at Howard University in Washington, D.C., Scott describes himself as a “private intellectual” who frequently shares his views on race, politics, and historiography with other academics on his public Facebook page. But as his discipline has grown more contentious, he has increasingly ventured into public view.

First came a long essay in the journal Liberties challenging the view that the Thirteenth Amendment led to the development of convict slavery, a system of forced penal labor that arose in the United States after the abolition of slavery. Then, in an interview with the Chronicle of Higher Education, he warned that historians have endangered their credibility through a “reductionist” focus on slavery and racism over the achievements of African Americans over four centuries. He has been outspoken in his criticism of the New York Times’s 1619 Project, including its inclusion in classroom curricular materials.

Scott’s concerns are grounded in a career spent advocating for the study of Black history. He formerly served as the president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, formed over a century ago by former Howard faculty member Carter G. Woodson. In 2008, he edited and released a previously lost manuscript by Woodson, who is often referred to as the father of Black history.

In an interview with The 74’s Kevin Mahnken, Scott argued that the fabric of American civic life has been dangerously frayed by politics, and that educators needed to help students recover a “shared culture.”

“The stakes of the past are nothing like the stakes now,” Scott said, referring to past battles around American history in schools. “You may have had one or two people at a school board meeting trying to outlaw one or two books, but now we’re looking at every red state changing laws about what teachers can teach.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 1619 blowup isn’t the first big debate over the teaching of U.S. history, but it seems like the most intense we’ve seen in a long time. What factors do you think led us here? The release of the 1619 Project, and reaction to it on the political right, may have been the proximate cause, but it also seems like cultural politics have been headed this way for a while.

It’s the collapse of multiculturalism. What brought it to a head was the arrival of Barack Obama, and what that meant to people on both sides of the political divide. One side thought it would mean racial progress, in the sense that the needs of the Black community would be better met. There’d be affordable education, affordable housing, and we’d have more progressive politics. The other side said, in effect, “They’re now playing quarterback, and we’re represented by a guy who’s not like us.” And what better way to express that than by saying he was a Muslim born in Kenya?

I trace a straight line going all the way back to the 1960s and the end of the white supremacist Democratic Party. Some of those people found a home in the Republican Party — for a price. The price of the ticket was this: “We’ll talk about and the excesses of liberalism on race, but we’re not a white supremacist party, and we’re going to keep you in the background.” And by the time you got to Obama, the people who had been in the Klan had retreated from politics. They couldn’t articulate their racism fully until Trump came along. There was an acceptance of a multicultural society where Republicans would elect people like Bobby Jindal and Tim Scott and tell you that diversity was our strength. But after Trump, multiculturalism dies out on that side.

On the left, it dies out as well. It dies out because people thought they were getting a return to Great Society liberalism with race-conscious programs for Black people, and a lot of those folks were disillusioned. With the economic decline of the 2010s, Black wealth dropped precipitously, and it’s as if the Civil Rights Movement had done nothing for Black people economically. There’s a denial about the society-wide growth of inequality, and instead of this being talked about in class terms, it gets talked about in racial terms.

These developments are related to the ideas that had become important in the academy, like white supremacy and white privilege. Those are being taught in the academy, people are going to school to become teachers, and they’re taking a body of courses that includes this. This stuff isn’t necessarily taught in education courses, but maybe it finds its way into them. The association I was with [the Association for the Study of African American Life and History] published the Black History Bulletin; it’s not a famous journal, but it has teachers who write lesson plans in it, and you could see the influence there. You started seeing it in the social studies groups that the teachers run. And so it starts trickling down as part of the education teachers would get, either directly in school or in some of the workshops they attend to keep their accreditation — It’s in the cultural and intellectual milieu.

You get terms like “white fragility.” There’s less promotion of anything multicultural, and it creates an environment where everybody increasingly becomes combative. The whole concept of white fragility is pejorative; you could frame it in a non-pejorative way, but it matters that it was framed in a pejorative way. You get people saying that there is no such thing as white, European culture.

This didn’t have to be a polemic, but when the tone changes, all of this is weaponized. You could say that some of this starts with the 1619 Project, but it’s important to know where the first shots were fired. I’m no student of the Hundred Years’ War, but I would guarantee that they were not fighting every day.

Could you trace the development of how schools have approached the teaching of racism and slavery — and how, in your view, the 1619 Project is tackling things differently?

People will say that conservative textbooks since the 1960s have tried to erase slavery by calling Black people anything but slaves — and, if they have to talk about slavery, to suggest that it’s just one of several different labor systems in the New World. So you hear slavery discussed, fleetingly, as a labor system in certain states. It gets glossed, and when it’s dealt with, it’s as a fairly benign institution. Some people see it as hearkening back to the Lost Cause narrative of the happy slave.

But we should also remember that something like Roots has already been part of popular culture and had been in the classroom since the ’70s. And the emphasis on slavery and Black history— this is where the 1619 Project really deviates — has been on cultural continuity with West Africa and a sense of pride in that cultural continuity.

That’s the predominant K-12 message I saw when I started at the Association, and by the way, it’s still the predominant message. People lost jobs in the ’60s and ’70s if they ran around saying that Black people had been crushed by slavery and lost their culture. That was the Nation of Islam position, and the Nation of Islam was understood by the mainstream of the Black community to be extreme and wrong.

The 400th year marking the origins of slavery in the New World would have been expected, in the tradition of Roots, to be a celebration of cultural achievement and African retentions. That’s how it was done virtually everywhere else! There was a state commission on the anniversary of 1619 in Virginia, and everyone signed off on it, conservatives and liberals alike. The traditional 1619 story was accepted because it had pretty much become the multicultural story.

The New York Times Magazine version of history doesn’t talk about Black people so much as it talks about what white people did to Black people. It becomes a story of unrelenting oppression at the hands of white people with everything being measured in racism, including how you take the highway to work. It wasn’t completely self-created — Nikole Hannah-Jones is a product of the same cultural experience over the last 12 years, part of that same zeitgeist. At the same time, she’s saying it from a very exalted platform, so that the mainstream 1619 celebration gets bumped in favor of a narrative that comes from a different intellectual movement.

So much of what we’re seeing in this alternative interpretation of 1619 has now become the dominant interpretation. And behold! How did that happen? Because it comes from the New York Times, the institution that many people on the center-left genuflect to. And now in many red states, where Black history had to be fought for from 1926 forward — success in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, Black History Month celebrated everywhere — it’s now being called into question. That’s progress?

It feels like the Trump administration’s reaction to the 1619 Project, and especially the curriculum’s rapid adoption in schools, was at least as important in raising the stakes of history education as the Times’s own product. What was your response to the short-lived 1776 Commission?

One of the things about the new, allegedly conservative stuff like the 1776 Commission is that it’s borrowed liberal ideology. American exceptionalism is a liberal project, and it’s always been a liberal project. It gets borrowed by conservatives in the absence of anything else. When you imagine a real conservative historiography, it really would be about innate inequalities along class and racial lines. It would be a true, thoroughgoing defense of aristocracy, and the slaveholding class.

Instead, you have a group of people today who, for lack of a better term, really are close to being fascist — we just have to admit that this is where some of these people are headed — but they don’t really have their own thing. The 1776 Commission’s report is basically a recooked Reaganite adoption of American exceptionalism that was tacked onto a Trump agenda by people who weren’t necessarily Trumpists themselves. It was a bizarre thing.

So Trump creates the commission, and the commission comes back with ’50s liberalism — and ’50s liberalism on race was American exceptionalism. In the mid-’50s, no one’s called America “systemically racist” yet. That’s a ’60s concept, and it gets talked about a lot in the ’60s. What you see in the ’50s is basically the belief that if you dismantle segregation and give Black people the right to vote — that is to say, if you dismantle real white supremacy — then we would be the liberal society we’ve always said we’d be. There’s the notion that we can live up to this vision, and there’s always been progress made toward this end. What they’re arguing against, just like any good ’50s liberal would have argued, is that there’s nothing permanent about American racism. That’s an awfully damned liberal position.

You’ve mentioned the way certain progressive intellectual tendencies trickled down from the academy into K-12 teaching, but that notion feels sort of incomplete to me. I wouldn’t have pictured schools of education as the same kind of hothouse intellectual environment as a graduate-level humanities department, for example.

Well, there’s a zeitgeist, right? You don’t have to take a course on Critical Race Theory to hear one of its cardinal concepts, which is that there’s a kind of permanence of racism in society. And of course, critical race theorists didn’t discover this; it was a Civil Rights Movement problem for intellectuals and policymakers. There was a need to categorize certain behaviors as “racist,” because we’re trying to condemn them. So discrimination on the basis of race becomes the standard definition of racism in the 1960s.

It’s not necessarily taught in all the schools of education, but every teacher would know this. Implicitly, they would know this. The critical race theorists didn’t discover this measure of discrimination, but it becomes one of their metrics for determining that racism still exists and is permanent.

It’s not even the only subfield thinking that way. The whole multicultural project is about how to root out discrimination from the schools! This is not to say that every teacher went to school and learned it that way, but it was part of the professional culture they entered.

When parents start saying — whether they’re being egged on by right-wing activists or not — that their children are being taught to hate themselves or feel guilty for what other people have done, it’s going to have consequences. Parents don’t want their children taught that they’re the source of the problem and that this problem is permanent. I mean, wasn’t multicultural education, going back to Carter G. Woodson, essentially an attempt to make everybody, including Black kids, feel that they weren’t inferior, weren’t less than, weren’t to blame?

So much of this is about pre-existing combat, and the combatants want to say that they’re just into truth-telling. But there’s so many truths you can tell, so why do you tell this truth, and why do you tell it in this way? Why is there this effort to poke the opposition in the eye? Part of the answer is that there’s a lot of frustration on both sides, and the cultural war is playing out that dimension among what would otherwise be perfectly reasonable people.

It seems like the political reaction of the last few years caught a lot of people by surprise. What’s your reaction to the movement in statehouses to limit the scope of what teachers can discuss in the classroom?

A lot of this stuff is just so East Coast-centric and blue state-centric. They don’t understand the nooks and crannies of this country, and they don’t understand how a school board functions. You’ve got people saying, “Let the teachers sort out what needs to be taught,” as if that was all that was at stake. They seemed not to understand that school boards ultimately have a say, that state departments of education have a say, and that legislatures have a say.

My whole thing from the very beginning was that this was not just a book, it was an attempt to transform K-12 education. You’re attempting to shape what’s going on in schools, and you’re doing so from the highest intellectual platform. It’s the most important newspaper in the country, and when that newspaper says it’s going to make an intervention in education, are you really surprised that the opposition was listening? And that Trump, who lives in New York, reads the New York Times?

Before all this, the history culture war mostly centered on monuments. Now it centers on the teaching of history itself. And what I want people to understand is that this is just not one event. It’s the escalation of a war at a critical juncture in American history, when anti-democratic forces are now in control of the Republican Party. Those anti-democratic forces are disenfranchising people, and this is the realm in which you are making these assaults, as if you’re not part of the broader fight?

Obviously, you’re not a fan of 1619. But what view of Black history would you like to see in K-12 classrooms? Is it that Roots version, the multiculturalist perspective that emphasizes themes of cultural continuity and pride in the achievements of Black people?

We live in a diverse, multicultural society. Public schools belong to all of us, and it behooves us to teach about our past in a way that respects everyone. Maybe the multicultural nirvana was never possible, but what counts is the good faith effort to be inclusive, to be respectful, and to realize that we’re on a boat at sea together. You can’t drill a hole in one side of the boat without sinking the other side.

Here comes the most uncomfortable truth of all: We don’t know whether white Americans will become a self-conscious ethnic group in their own right, but there are reasons to believe that they’re becoming precisely that. To the extent that they’re becoming that, they are part of this diverse America that has to be taken into account as well, and you can’t treat them as a default category with no culture and no history.

The fact of the matter is, white people are becoming one among many ethnic groups, and their anger is a reflection of what they feel to be the growing power of other groups. To the extent that their perception is creating a reality, we’re all going to have to deal with that reality. And the way to deal with that reality, in a pluralistic society, is to honor the identity group that presents itself to us. Because they’re far from powerless. We can’t pretend that they’re powerless, just like we can’t pretend that we have no power.

What I’m calling for is a return to multiculturalism as a procedural frame for how we go about educating our kids about history. As a good pluralist, I believe there’s a shared culture, and I don’t believe that everybody is an equal contributor to history at any given moment. World War II shouldn’t be reduced to “the multicultural history of World War II”; there’s an ethnic dimension to how people recruit for World War II, and there are stories we can tell about various groups during World War II, but those key battles are the key battles. History is not always reducible to a story of multiculturalism.

However we teach it, though, we need to be mindful that there is a diverse group of people participating. As a kind of modus operandi, how we teach history is what I’m most concerned about. The purpose should never be to make anybody in the audience uncomfortable to the point that this is grievance history. Because what happens then? Everybody gets to voice their grievances? I think that’s where we’re headed if we’re not careful.

One criticism I’ve heard about multicultural K-12 history was raised by the education historian Jonathan Zimmerman, who told me that schools have spent decades making room for heroes of new ethnicity: “We went from cheerleading for George Washington to cheerleading for George Washington Carver.”

Some of this is just the nature of K-8 history, which gets taught around biographies too much. K-8 will invariably be that way because biographies matter to kids. Woodson defended this by saying, “We won’t teach less about George Washington, we’ll teach more about Peter Salem.” That’s how he pitched this at the elementary level.

But even Woodson took the celebration of Douglass’s birthday and Lincoln’s birthday and transformed them into the commemoration not of two people — there were often celebrations of those two events — but of a whole group of people. There was still a biographical aspect in how he was doing it, but what made him a social historian was talking about the role that common people played in the making of history. Woodson at his best is beyond biography, but he got into a collective biography of how peoples contribute to the making of history.

What you could say the 1619 Project is doing at its best is to talk about the African American contribution to making America live up to its ideals. That’s actually a very traditional point of view within the African American community — that it’s our struggle that transformed America and makes it live up to its ideals. So everybody has done this, and we should continue to talk about different ways in which collectivities have shaped the country.

All of this is legitimate turf for future discussions of how history is written. It is a debate about how we want to tell our past, and it has got to get beyond simply grievance history. History that is propaganda for the sake of getting certain policy outcomes is not going to get us through this. And I really mean “get us through this,” because there’s a possibility that we rend ourselves on the question of race. The longest-standing question of democracy is, How much homogeneity is necessary? The assumption once was that if it’s too heterogeneous, a democracy can’t work. So we really need to ask ourselves, how do we go about teaching our past in a common way, so that we have a common project? We have to deal with history for the common weal.

I think this addresses the supply-side question of history education — you’ve got practitioners of Black history and women’s history and labor history who all want to have their say. But the public demand for historical knowledge seems to be so weak, to the point where most Americans demonstrate very little grasp of it at all.

America is a history wasteland, and February is about the only month where you’re going to get any American history. There are interviews and surveys showing that the average American doesn’t know who was on what side of the Civil War. How ironic is it, then, that we’re over here splitting each other’s skulls about this?

Having said that, one could argue that’s how we got here in the first place — that we have a lack of knowledge about our history, and if we’re going to make it through this, we have to do better at teaching history with civics embedded in it. We need to teach about shared government and shared culture, and if these things tend to go in one ear and out the other, we have to figure out how to keep it in people’s heads.

I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of this, but February used to be American History Month, not Black History Month. After World War II, the Daughters of the American Revolution started promoting February as American History Month because it had the birthdays of two major presidents, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. They went out and got the proclamations of presidents and governors, and it went through Lyndon Johnson. And the way they dealt with American History Month was the story of the WASP; they didn’t even talk about the white immigrants. And so American History Month was not a big-city affair, where all the immigrants were. (Laughter) It was really a small-town movement in the hinterlands. Phyllis Schlafly was a big deal in this whole thing.

But it just faded. I only caught onto this because I saw someone post online, “Do you remember when February was American History Month?” They were complaining about Black History Month, and another person said, “Oh yeah!” But by 1976, there were presidential proclamations for Black History Month, and nobody remembered that February was American History Month. This is what happens if you do this history that excludes people. So White History Month, if you will, failed; the people doing it wanted Anglo-Saxon Month, but they called it American History Month. They weren’t boasting about how Eisenhower saved Western Civilization, you know?

Do you think the general lack of knowledge among Americans about their past is why there’s this appetite for historical myth and misinformation? Or could it be the other way around, that the political pathologies of today are eroding our historical awareness?

There’s always been a market for popular history and what you were never taught in school. This is not something exclusive to African Americans. There’s a notion that schools are not serving us well. Yet there’s also a perception that the schools are serving someone else well — just not the cause I believe in. It’s hard to get across this point to people: “If I created a multicultural curriculum, I’d have to throw out a whole lot of stuff that you want to stay in, because you’re going to share time with other groups.” What that means is that the ultimate multicultural history would be disappointing to virtually all groups — even the best-faith efforts to be inclusive would still be met with, “They’re excluding us!”

This is a very particular moment. Social media has, on the one hand, made people more conscious of what is consumed as history, and it’s also led to the sense that the white story is not being told. You see this everywhere. There are certain white nationalists who will now falsely say that the Irish were slaves, and their story is not being told. There are people who say that, in the name of 1619, the true American history is not being told. So in this moment, the history has been politicized, and the history that serves one’s own cause is the history people are looking for. This sense of being excluded is because we don’t have a sense that we’re in this together anymore.

The obvious question is, were we ever all in this together? As you’ve acknowledged, battles over what history to include or exclude go back a long way, and inter-group relations have long been fractious in the United States.

The multicultural battle we waged between the ’70s and the 2000s was just not the same battle as the one we’re looking at now. Progress was made that is now denied. People act as though there was never a Black History Month in Montana, when there was; people act like everything was excluded from K-12 in Idaho, when it wasn’t. There’s a pretense that everything in textbooks has been the Lost Cause until this very day, and that everything Woodson attempted to do in the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s went to naught.

And of course, the Civil War was there also. The people who want to pretend that we started teaching about Critical Race Theory and stopped teaching about the American Revolution, that’s false. If they think schools have been teaching that the Revolution was caused by slavery, it’s not really taught that way. But let’s also not deny that the 1619 Project was poised to go into public schools teaching precisely that. They were moving at 100 miles per hour, and if people didn’t scream and yell, that’s what would have been printed and disseminated to teachers.

So there was an effort to change the narrative in such a way that people couldn’t recognize themselves in their own history. The argument was, “It’s one telling of the story, one narrative among many…but it’s what we want you to teach in schools.” Anybody who understands K-8 education should understand that you don’t give multiple narrations of history to children. You don’t tell them that it could have been this way and could have been the other way. It’s just not how elementary school is taught.

I’m here to say that the history that gets taught is not as important as the effort to build a shared culture in society moving forward. You will not exterminate your enemies, and you’re going to cohabitate the same territory. The question is how much damage you’ll do to each other and to everyone else. We’re at that point.

Lincoln would say that you can destroy your enemies by making them your friends.

That’s precisely my point.

What makes this different for me is that I’m a South Side ghetto boy, but I served in the U.S. Army with people from all walks of life during the Cold War. So I can’t be that partisan in the culture war — I know it’s going nowhere good. You’re not going to get the reparations that some people think you’ll get from amassing this evidence of repression. And you’re certainly not going to get it by poking the other fella in the eye with this history that you say indicts them. It’s just not how this is going to be done, unless there’s some third party that takes over the entire government and gives what you think you deserve as the spoils for destroying the country. It would be the Chinese Reparations Committee hearing the grievances of African Americans and Native Americans.

Changing the subject a bit, you’ve described yourself as the product of Catholic education, all the way up to attending Marquette University as an undergraduate. What effect did that have on your scholarship and your development as a human being?

My context of Catholicism is really from the vantage of a set of schools that were servicing Black communities. They were really white Catholic institutions serving a Black Protestant population. I happen to be Catholic, but I was probably one of a minority of Catholics going to those grammar schools and high schools.

This was a moment in history after the World Wars. My father boxed in the Catholic Youth Organization in the ’30s, but he didn’t go to a Catholic school. In a lot of the urban North, as the Catholics left the inner city, they were replaced by Black folks during the Great Migration. The schools were only dealing with Catholics before Vatican II, and much of the Black people were committing apostasy to get an education, going from Protestant to Catholic in the ’50s.

The motto at my high school was “Unto Perfect Manhood”; there was an effort to make us good Christian, Catholic men, and to some extent, I’m a product of all of that. The Catholic schools became an opportunity structure for social mobility for me and my brother and a whole lot of other people. Being a Black Catholic on the South Side of Chicago during the Great Society, that’s what shaped me.

It was only much later that I realized that Catholics were some of the earliest advocates for school choice, and that goes back to trying to use public funds to support religious education. And I’m a decidedly liberal person who says, “Nah, not with my tax dollars.” I’ve understood choice to mean opting out of public schools at your own expense, and politically, that’s where I still come down. It is conceivable that we could all take our fair share of the tax dollars and let people take them to whatever kind of school they want to, but if this moment tells me anything, it tells me that we collectively would be better off with shared experiences. If you want to opt out of that shared experience, maybe you should underwrite it yourself.

I’m for public schools as a venue for those shared experiences, and I’m actually for all kinds of incentives to join the military in pursuit of common experiences. I believe the draft ended in ’74, and here we are roughly 50 years later without that common experience of military service. If you’ve never met that poor white kid from West Virginia, if you’ve never met that brown-skinned kid from Samoa, if you’ve never met the guys from Puerto Rico, if you’ve never met that Black Mississippian, then you really don’t understand what’s out here in this country, and you don’t know how people share a culture and share experiences.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)