Race, Trump & History:

Weeks Before Election, President Leaps Into Culture War Skirmish Over Teaching 1619 Project

By Kevin Mahnken | October 5, 2020

Updated October 6

Standing at a podium in the rotunda of the National Archives Building, with original copies of the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights as his backdrop, President Trump addressed the White House Conference on American History. It was Constitution Day, Sept. 17 — roughly six weeks before voters would decide the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

Trump made news in his 15-minute speech by announcing the formation of a federal panel to promote patriotic education. The commission, he said, would help to clear out a “twisted web of lies in our schools and classrooms” that deliberately misrepresented the glories of the nation’s past. While aiming rhetorical daggers at the spread of critical race theory and workplace sensitivity trainings, the president reserved special condemnation for the 1619 Project, launched by the New York Times Magazine last year to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first slaves in colonial Virginia.

“The left has warped, distorted and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods and lies,” he said. “There is no better example than the New York Times’ totally discredited 1619 Project. This project rewrites American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom.”

The president had already raised the issue of U.S. history several times in the election’s home stretch: When the White House released a set of second-term goals ahead of the Republican National Convention, one of the two education-related bullet points was a call for schools to “teach American exceptionalism.” Trump has also threatened to withhold federal funding from schools that teach a much-hyped 1619 curriculum developed jointly by the Times Magazine and the Pulitzer Center. Although events overtook the messaging war to an extent — Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died the very next day, and Trump himself took to his sickbed with COVID-19 just two weeks later — the tone had already been set.

The 2020 campaign is far from the first time that efforts to update history curricula have made ripples in national politics. But whereas previous skirmishes have erupted over the function and conduct of history instruction, they never drew the focus of a sitting president just weeks before Election Day.

Mary Frances Berry, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania and a former chair of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, called the conflict “an echo of earlier dustups” around U.S. history, such as the battle that torpedoed the National History Standards in the 1990s. But this iteration has been complicated by the convulsive racial politics of recent years. And in Donald Trump, who has played no small role in elevating racial grievance to the fore, the arguments of the 1619 Project have found an eager combatant.

“This period in which we have people getting shot and killed … and we have Trump — it’s a context in which the 1619 Project becomes part of the fodder to fight over race,” Berry said. “Those who want to put racial division back in a box and say, ‘We don’t need to do anything about it,’ won’t like 1619 because it puts it right in your face. And those who think that something must happen want it out there and want people to contend with it.”

Since its unveiling a little over a year ago, 1619 has won widespread acclaim for its unsparing perspective on manifestations of racial injustice extending from the Middle Passage into the present day. In lengthy essays studded with detailed sidebars, the project’s authors explore the historical roots of modern-day ills, from the racial wealth gap to the underfunding of mass transit to America’s harsh system of criminal justice. As a measure of its glowing public reception, teachers quickly began incorporating elements of the series into their history lessons.

But the public response did not end with adulation, and its detractors are not numbered merely among conservative Republicans. Within months of its publication, a group of well-respected historians signed an open letter to the Times Magazine seeking corrections to the project’s assertions about the centrality of slavery within the context of the American Revolution and the pre-Civil War economy.

The 1619 Project’s principal claim — that the true birth of the United States came not with the signing of the Declaration of Independence but with the inception of slavery — has been called into question, along with the openness of project creator Nikole Hannah-Jones and her collaborators to expert critique.

Jonathan Zimmerman, a historian of education at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed to what he called a “significant” inaccuracy in the Times Magazine’s initial claims about slavery and the Revolution. Nevertheless, he said, the intense spat over the 1619 Project, and even its sudden cameo in our ongoing culture war, offered Americans both inside and outside the classroom an opportunity to reflect on their country’s past and present.

“What a historian is supposed to say is, ‘Oh, we’ve always done this.’ And it’s true that we have always debated history in different times and places, always tried to tailor it to our political predilections. But there is something different about this moment.”

In an interview with The 74, Hannah-Jones stood by the interpretation of facts laid out in the 1619 Project. The controversy over some of its conclusions, she said, was due partly to the reality that the country is undertaking “a lot of questioning of the way that we’ve commemorated, the way that we have taught, the way that we have embraced a certain exceptional narrative of America.”

“It is really about wrestling over who can control the narrative of the country that we live in,” she said.

Fact-checking history

Although the 1619 Project was initially conceived as a special edition of the New York Times Magazine, it didn’t stay within the glossy covers for long. Indeed, it dominated the media in the months that followed, generating a live event series and a podcast. Luminaries like then-presidential candidate Kamala Harris took to Twitter to sing its praises. And the accolades kept coming in 2020, when the series received three prestigious National Magazine Awards and Hannah-Jones was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for commentary. By that time, according to the Pulitzer Center, some version of the 1619 curriculum was in use in 4,500 classrooms around the country, including large-scale adoption in schools in Chicago, Newark and Buffalo.

The criticism that followed originated from venues both predictable and offbeat. In The Wall Street Journal’s famously conservative editorial page, civil rights activist Robert Woodson decried that the project’s “insinuation that Blacks are born inherently damaged by an all-prevailing racism.” Meanwhile, the obscure World Socialist Web Site made attacking 1619 and Hannah-Jones a kind of project of its own, denouncing its thesis as “a racialist falsification of American and world history.”

Obscure or not, the website scooped the mainstream press by exposing significant dissatisfaction with the 1619 Project among some of the most famous living historians. It published lengthy and critical interviews with Pulitzer winners Gordon Wood and James McPherson, along with acclaimed scholars Victoria Bynum and James Oakes, all of whom said that Hannah-Jones and some of her collaborators had gotten key historical facts wrong and overreached in their claims about the inescapable legacy of slavery in American life. Soon enough, all four signed on to the open letter asking the Times Magazine to issue corrections and provide detail about its research and fact-checking processes.

The experts’ gripes focused on a few areas, but the most prominent came in Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay, in which she wrote that the preservation of slavery was a primary motivation among American revolutionaries fighting for independence from the British Empire. After the claim was energetically contested, the Times issued a clarification in March acknowledging that only some colonial leaders were motivated to revolt by a perceived threat to slavery.

Further complaints were raised, hinging on both fact and interpretation. Hannah-Jones had written that “for the most part,” African Americans had “fought back alone” against racist tyranny — an omission, the letter writers argued, of the multiracial coalition that won the Civil War, abolished slavery and brought about the Civil Rights Movement a century later. Economic historian Phillip Magness argued that sociologist Matthew Desmond’s essay relied on research that grossly overstated the importance of the plantation system to the antebellum economy.

A number of scholars also publicly defended the project, including some who accused its critics of holding an outdated view of America’s founding. In one nuanced reaction, Leslie M. Harris, a Northwestern University historian who had helped fact-check Hannah-Jones’s essay, lamented that the Times Magazine had disregarded her advice to drop the argument about the Revolution — even while defending 1619 as a valuable, if imperfect, “corrective history.”

Hannah-Jones conceded that the project was not “perfect in all ways” but argued that historians were themselves caught up in the politics of the moment. The fact that some might have opted for a different interpretive lens than she was “not discrediting,” she added.

“This was an essay that spanned 400 years of history, and one could take any one fact in that story and say, ‘She should have expounded more about that fact,’” she said. “I’m not sure how I’m supposed to answer that, frankly. I wrote an essay making an argument … that I thought was important. I did not write a book about Abraham Lincoln, and I did not write a book about the founding.”

But the most vocal detractors haven’t gone away. Oakes, a two-time winner of the prestigious Lincoln Prize and one of the most widely cited scholars on the subject of slavery and the abolitionist movement, said that he was both discouraged by the Times’s response to critics and worried that “a good deal of misinformation is going to go into the school system with the 1619 Project.”

“All they have to do is say, ‘Yes, we’ve made a mistake, and we welcome all these critics showing us where we’ve made mistakes, and we’re committed to making sure that those mistakes are corrected so that what goes into schools is accurate,’” he said. “They’ve never taken that position.”

Zimmerman countered that, notwithstanding the factual errors highlighted by his fellow historians, the 1619 Project had done a public service by bringing attention to the tangled system of racial servitude, violence and theft that had characterized the American story.

“It’s good for Americans to spend 30 seconds considering the fact that during the Revolution there were millions of enslaved people,” he said. “This is not in any way to diminish the error, which is significant, but I would still say that the debate surrounding the 1619 Project is one of the best things to happen in my career. And you don’t have to endorse everything [in it] to say that.”

Research shows that American students possess a limited knowledge of early American history and the primacy of racism’s role within it. A 2018 report from the Southern Poverty Law Center found that while most teachers felt comfortable discussing slavery in the classroom, only a small fraction of the student population identified the institution of human bondage as the central cause of the Civil War.

Oakes agreed that there exists a need for more and better history instruction — especially around slavery, which he called “the central theme of my career.” But there is danger, he continued, in taking up a new form of “consensus history,” one that suppresses the perennial struggles in American democracy in favor of Manichaean simplifications.

“The conflict that arises in the American Revolution — you start getting free states and slave states, and try to imagine American history from the Revolution to the Civil War without those designations — gets ironed out, taken away,” he said. “You can’t explain American history that way. It’s not the subject matter that’s the problem; it’s the way it’s treated.”

A nation ‘seriously under question’

No stranger to simplification, the president has chosen a foil already widely hated on the Right. Even before Trump excoriated it as “ideological poison,” Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton, viewed as one of the GOP’s rising stars, proposed a bill to ban the use of federal funds in teaching the project’s curriculum. Just a week after its publication, conservative icon Rush Limbaugh dubbed it a “hoax” and said that it represented “the end of journalism, officially.”

Berry, who surveyed the partisan landscape for decades during her tenure on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, said that the project’s emergence as a political football was predictable.

“It was good campaign fodder to come out with this, and it should appeal very much to [Trump’s] voters,” she said. “It’s consistent with his approach to dealing with race and education and civil rights. So I’m not surprised at all because it was ripe for the picking, so to speak.”

The bitter politics mirror previous debates around school history curricula, which have effervesced into the popular discourse more than once in recent years. The backlash against perceived leftist encroachments into public schools has typically been the trigger, observed James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association.

“There were complaints in the ’50s that any teachers who sang Pete Seeger folks songs in class were practicing Communist indoctrination; that was a little overwrought, in retrospect,” he said. “In many ways, some of this hysterical concern about the impact of the 1619 Project does remind me about some of the hysteria about Communist influences in the classroom in the 1950s.”

Recent decades provide fresher examples. Just a few years ago, education officials in Texas and Oklahoma attempted to ban the use of a new AP U.S. History framework that was seen as jargon-filled and politically slanted. References to the “bellicose rhetoric” of Ronald Reagan (especially compared with sunnier depictions of Democrats like Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson) and the “white racial superiority” powering America’s Manifest Destiny period would leave students “ready to sign up for ISIS,” said neurosurgeon Ben Carson, who was about to launch his 2016 presidential run.

The furor continued when the Republican National Committee issued a resolution condemning the new curriculum. The College Board, which administers the AP exams and had spurred the controversial revision, ultimately backtracked on many of the changes. In its re-released framework, mentions of the words “racism” and “xenophobia” were omitted entirely.

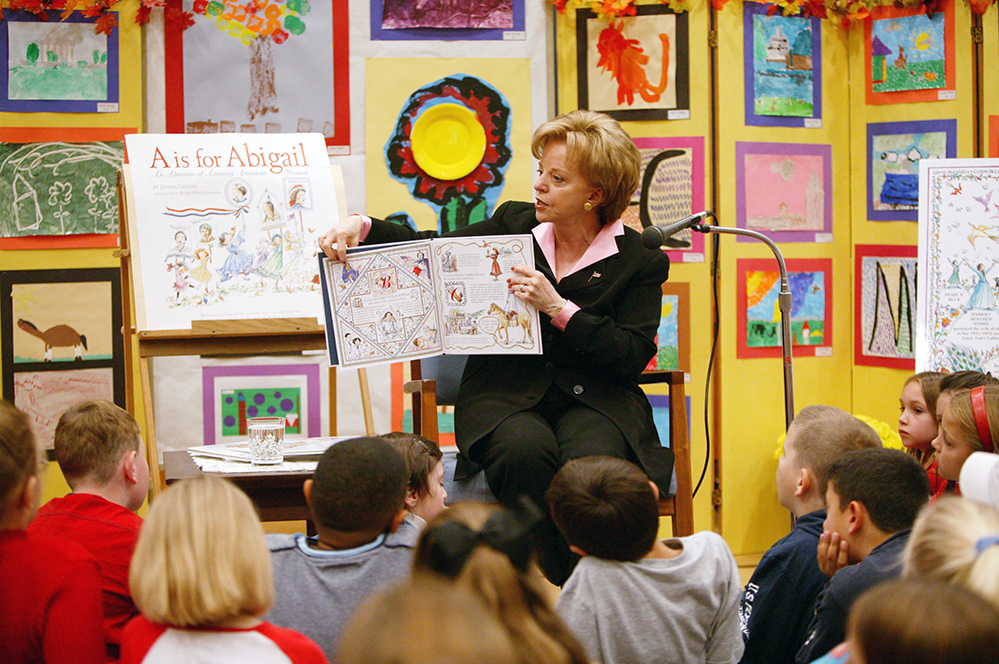

An even more dramatic clash came in the 1990s, when a curricular body at UCLA spent nearly three years developing the National History Standards, a set of teaching guidelines to be adopted voluntarily by states. They were assailed almost immediately by Republicans led by former National Endowment for the Humanities chairwoman Lynne Cheney, who complained that the standards omitted references to famous Americans like the Wright brothers and Robert E. Lee in favor of commemorating Harriett Tubman and the National Organization of Women. In the aftermath, the U.S. Senate passed a non-binding resolution repudiating the initiative by a vote of 99-1.

Over time, American classrooms have come to include depictions of U.S. history through non-white, non-male perspectives. A 2017 article by LaGarrett King, a professor of social studies education at the University of Missouri, found that racial diversity had increasingly penetrated K-12 schools through elective classes and partnerships with institutions like the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The celebration of Black History Month has spread throughout the country and the world, and a 2008 survey found that high schoolers listed Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriett Tubman and Oprah Winfrey on a top-10 list of national heroes.

Even allowing for those developments, however, King believes that the complex history of American race relations has been buried beneath an optimistic story of forward progress. Episodes like the desegregation of schools, which led to an ugly white backlash and thousands of Black educators losing their jobs, are sanitized as unalloyed triumphs.

“We include these particular people, maybe a few viewpoints, but we don’t change the narrative,” King said. “We freeze Martin Luther King with ‘I Have a Dream.’ We situate Rosa Parks as this tired seamstress. We know Harriett Tubman from the Underground Railroad. But we don’t necessarily discuss the history that’s contentious. Black history is contentious to those progressive narratives.”

Zimmerman echoed that sentiment, arguing that for much of the 20th century, well-intentioned multiculturalism had swollen U.S. history textbooks with the exploits of a diverse array of protagonists: Christopher Columbus, Johann de Kalb, Crispus Attucks. But the lessons remained blissfully celebratory, even as “we went from cheerleading for George Washington to cheerleading for George Washington Carver.”

“Now the whole nation is seriously under question,” Zimmerman said. “The 1619 Project’s advocates aren’t asking for new figures to be included in the same old narrative; they’re questioning the very contours of the narrative itself. I think that’s great, provided that it’s framed as a question rather than a new set of answers.”

Twilight struggle

As of yet, with millions of students still learning remotely and a chaotic election in its closing weeks, it’s unclear whether 1619’s footprint will grow in K-12 schools or a conservative backlash will lead educators to steer clear of the curriculum.

President Trump’s rhetorical campaign against the project has elevated it above earlier battles about U.S. history into a kind of twilight struggle that also encompasses the fate of contentious monuments and the names of army bases. David Campbell, a political scientist at the University of Notre Dame, noted that the racial entanglements of the past few years — especially after a summer of protests following the police killing of George Floyd — had raised the salience of quarrels about American history and culture.

“It’s not as though race were irrelevant to the earlier debates, but it’s certainly front and center now because of the 1619 Project in a way that it wasn’t before,” he argued. “And whenever anything becomes racialized, it raises the stakes for it, and that’s what we’re seeing. It’s also why it would be attractive for Trump, who of course never shies away from injecting himself into racial debates in the country.”

Hannah-Jones, who said she doubted whether the president had read the 1619 essays, argued that he had seized upon it as a useful target in an election year that has been a kind of “reckoning” — both with the brutality of slavery, secession and Jim Crow and with the present-day horrors of police violence.

“The only reason that the 1619 Project is even being mentioned by the president right now is that it’s part of this larger culture war that has to do with what brought him into office in the first place,” she said. “I think … white Americans are particularly primed for the message the president is putting forth.”

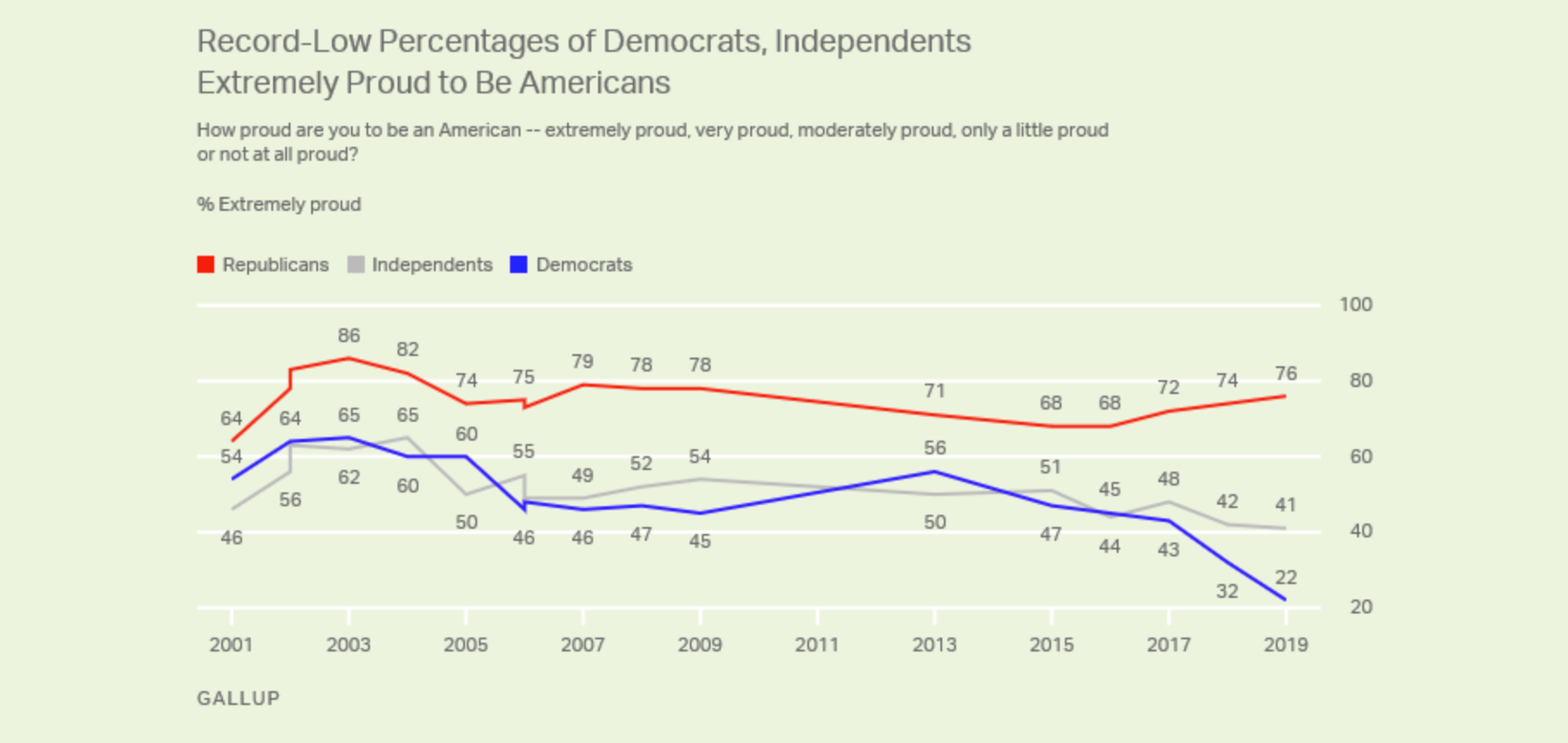

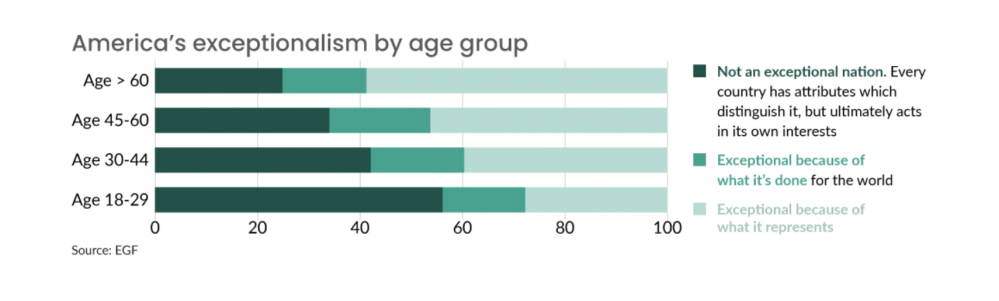

The 2020 election comes at a time when Americans’ surety in their national purpose and ideals is sorely diminished. While Republicans have always been more likely than Democrats to declare themselves patriotic in surveys, the recent partisan divergence on that issue is jaw-dropping: Just 22 percent of Democrats said they were “extremely proud” to be American in a 2019 Gallup poll, compared with 76 percent of Republicans. In a Eurasia Group Foundation poll this year, a shrinking number of respondents were willing to call America an “exceptional” nation.

Campbell noted that even while serving as a proxy dispute over racial attitudes and love of country, the row over the 1619 Project is also leading to a partisan role reversal. Typically, Republican politicians are especially jealous advocates of local control of schools against governmental incursions from the state. Now the party is calling for ambitious federal steps — including a commission on patriotic education that, even if it were formed, Campbell noted, “[could] not dictate curriculum across the country.”

King, who works with active and pre-service teachers, does not believe that the 1619 curriculum poses a threat to the largely pro-American orientation of K-12 history instruction. Like countless other workbooks and modules provided by third parties for use in the classroom, he said, it would be available as a resource for teachers to use or ignore.

“I don’t see 1619 as the be-all, end-all of how we should teach slavery,” he said. “There are some really good essays in there, but just like any educated person, you pull from different stuff.”

For his part, Oakes called the president’s proposals “an abomination.”

“I have no more interest in patriotic American history than I have in denunciatory American history. You don’t get patriotism or cynicism from history; ideally, you get wisdom. And it seems to me that nobody in this debate is interested in that particularly.”

Lead Image: President Trump during the White House Conference on American History at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 17. (Photo by Saul Loeb / Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter