Analysis: Learning About Reconstruction Is Critical to Understanding This Country’s History. But No Era Is More Neglected in Schools, New Report Finds

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“It’s impossible to understand the rest of the history of the United States without an understanding of Reconstruction,” wrote a Louisiana middle school teacher last spring in response to a survey from Zinn Education Project researchers. The survey stemmed from our Teach Reconstruction campaign to advocate for the teaching of this era and its legacies. Asking to remain anonymous, the teacher continued: “You risk being on very dangerous ground if you begin to make connections between Reconstruction and today. This is a true danger in 2021.”

These two ideas — that learning about Reconstruction is critical to understanding this country’s history, and that teaching about it is dangerous — should be at odds with each other. But no era of U.S. history is more instructive and neglected in K-12 education and public memory than Reconstruction. Historian Hilary Green has called it “essential for not only understanding the creation of the modern United States, but also how the unreconciled legacies from emancipation and Confederate defeat shape the present.” These unreconciled legacies offer answers to today’s inequities and possibilities for a better society. Teaching about them challenges the social order, which brings backlash from those who support a discriminatory status quo. This is the “dangerous ground” of Reconstruction education.

Our survey yielded hundreds of replies from educators across the country, who shared their classroom experiences and expressed similar sentiments. At the same time, bills, resolutions, and other state and local efforts to ban the teaching of “divisive topics” proliferated. These measures carry a host of consequences for teachers who dare affirm the existence of racism and acknowledge the injustices their students encounter.

In this climate, the Zinn Education Project has released “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction” — the first comprehensive report on Reconstruction’s place in social studies standards across the United States. Gathering these standards and educators’ perspectives provided insight into the nature and extent of the barriers to teaching effective Reconstruction history, which led us to make recommendations for improvement. We concluded that most state Reconstruction standards are inadequate at best and should be radically transformed.

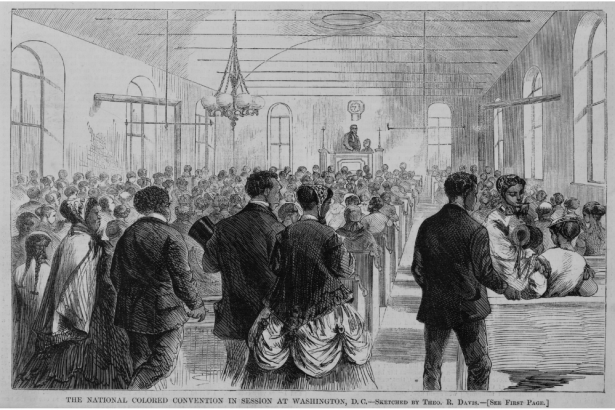

Why is it so important to study this era? Because Reconstruction was a Black-led movement to build a more just society from the ground up. The period after the Civil War was full of possibility for economic equity and progress for multiracial democracy, but it was soon crushed by white supremacists precisely because of its successes. The ramifications of Reconstruction’s dismantling still reverberate today, and so do its blueprints for an equitable future — from the foundations of civil rights laws, to enduring racial disparities in education, labor, health, wealth and the criminal justice system, to struggles over the idea and practice of democracy.

Learning about Reconstruction and its legacies disrupts both the myth that U.S. history is one long victory march from slavery to a post-racial present and the complacency that myth is designed to produce. For these very reasons, elites concealed the true history of Reconstruction in scholarship and popular culture well into the 20th century, pushing white supremacist fables and a historical amnesia that we see in today’s antihistory education efforts.

Why look at social studies standards? Because standards reflect the historical narratives endorsed by people in power and affect school curricula. It is troubling, for example, that standards in Alabama, Oklahoma and Tennessee refer to “carpetbaggers and scalawags” without any context for or analysis of this language. These terms were mainly used by white Southerners to denigrate Northerners (carpetbaggers) who moved South and white Southerners (scalawags) who sided with Republicans in support of Reconstruction. Using these words in this way encourages students to view Reconstruction from the perspectives of white supremacists who opposed it.

Standards in over a dozen states also include relics of the Dunning School, a once-dominant approach to scholarship that denied Black achievements and celebrated white supremacy — casting Reconstruction as an illegitimate enterprise replete with “failures.”

And many standards emphasize top-down histories. Florida’s, for example, include a long list of Reconstruction’s “policies, practices, and consequences” largely organized around Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, the presidential election of 1876, and state and federal laws.

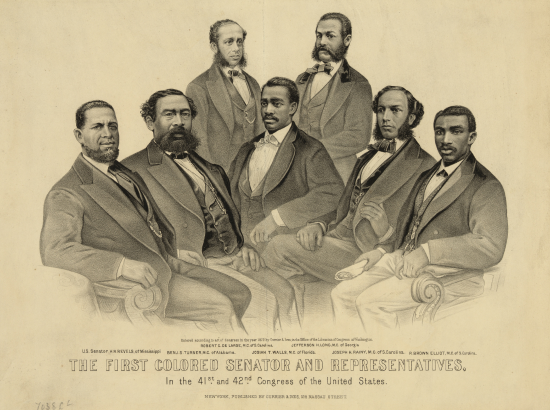

Another overlooked, but equally crucial, element of standards is what’s not there. For instance, only Massachusetts’s standards mention and link white supremacy to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, the passage of Black Codes, the emergence of Jim Crow and the toppling of Reconstruction. The vast majority of the rest erase the equitable economic, political, and social aims and gains of over 4 million formerly enslaved people and their allies. They neglect how African Americans organized to fulfill the promise of freedom — fighting for access to land and fair labor, achieving political representation, championing public schools, nurturing communities with joy and creativity, catalyzing civil rights laws. And they ignore the overwhelming resistance from white people united against multiracial democracy. These are the stories of Reconstruction. They are the pressing issues we face today — the points eclipsed in our country’s social studies standards.

Reconstruction is more than a Southern story. In every state, movements for multiracial democracy and justice arose, redefining freedom and contending with white supremacy. Which is why the report incorporates historical documents and vignettes from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Doing so tells a more complete story and brings Reconstruction’s relevance to educators and students who might otherwise dismiss it as someone else’s legacy.

The report describes an array of additional barriers to the teaching of Reconstruction — including a lack of collaborative professional development, pedagogical materials, funding and time for educators to dedicate to this history, compounded by the many ways standards miss the mark.

Ultimately, the report is a resource for advocating for rigorous Reconstruction education in K-12 classrooms and resisting the current movement to suppress truthful education. Because those who marshal legislation and intimidation tactics to ban teaching about racism know, too, that the erasure of history matters.

Mimi Eisen is co-author of the report and a program specialist for the Zinn Education Project, which promotes and supports the teaching of people’s history in middle and high school classrooms across the country.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)