Genocide ‘In My Own Backyard’

North Carolina Educators Ignored State’s Eugenics History Long Before Critical Race Theory Pushback

By Asher Lehrer-Small | August 10, 2021This story is published in partnership with The News & Observer.

Even as a young girl, the shadow of a dark history hung over Orlice Hodges. At seven years old, she remembers her grandmother offering an explanation — chilling in retrospect — of what happened to young women taken away by social workers: they went to Black Mountain to get “fixed.”

“I used to always wonder, what do they mean by ‘fixed?’” the North Carolina native told The 74.

Only as she got older did the awful meaning become clear. “Fixed meant sterilization,” she understood. “They were sterilized.”

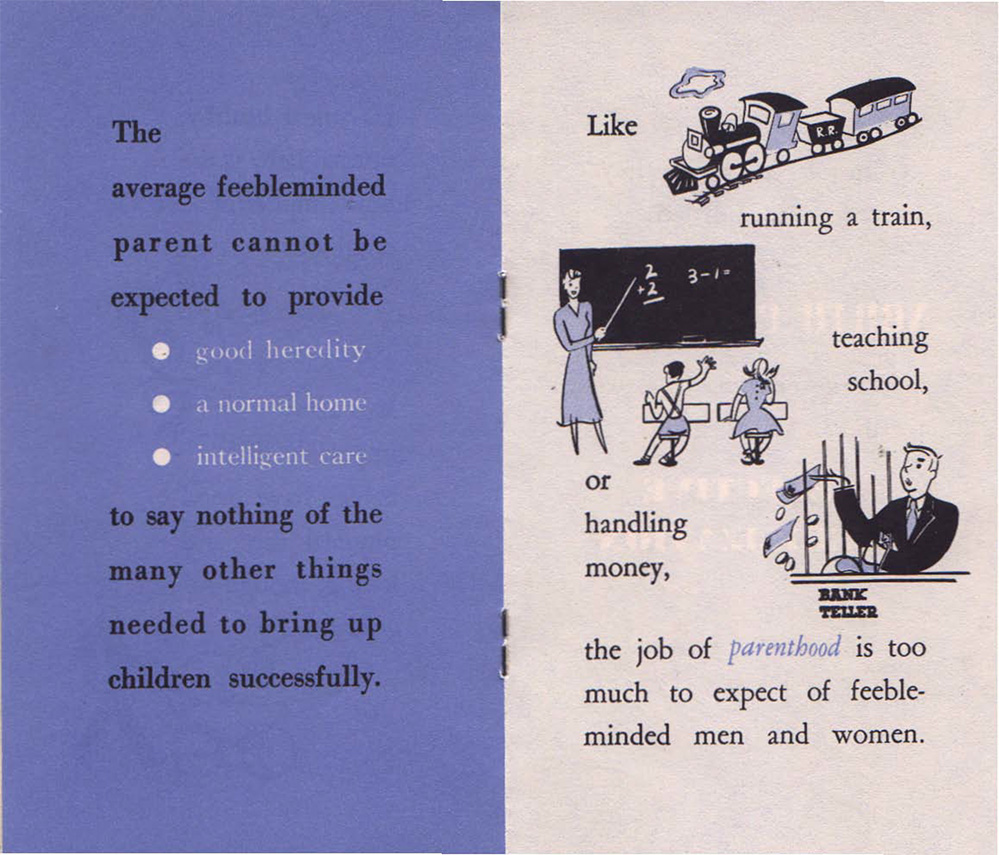

Her own aunt, according to what Hodges was told by family members, was one of the 7,600 people sterilized, or medically robbed of the ability to have children, by North Carolina between 1929 and 1974 under the state’s eugenic sterilization law. As a young, Black woman growing up in Winston-Salem in the 1960s and ‘70s, she could not help but know about the program, which sought to “weed out” disabled and so-called “feebleminded” individuals. By the time of her childhood, the effort had become distinctly racial, with more poor Black women forcibly sterilized than any other group.

Countless others, when Hodges was a girl and up until today, remain unaware.

“Why was that never mentioned?” wondered Skylar Sharkey, a rising senior at Middle Creek High School in Apex, North Carolina, upon learning about her state’s history of eugenics for the first time as a high school junior. Thanks to a scheduling glitch this past spring, she landed — by what she now sees as a fortunate accident — in an elective course that covered some of the grimmer moments in her state’s history. It included information she had never had the slightest inkling of.

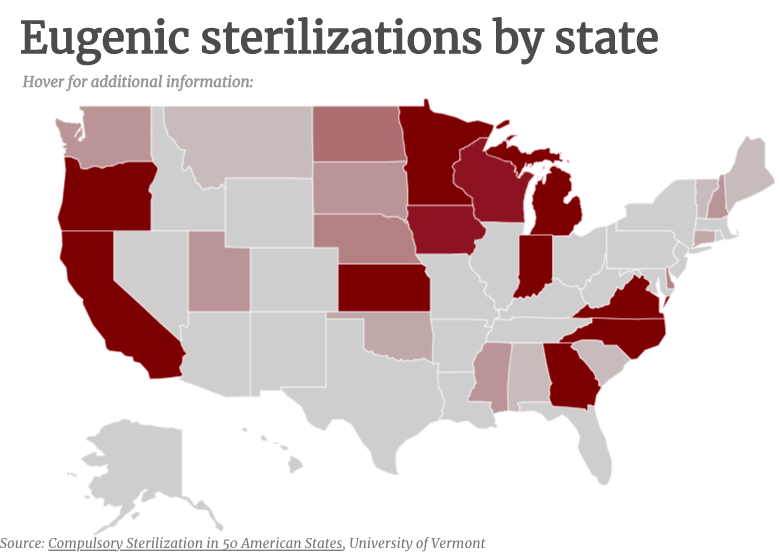

Over 30 states in the U.S. enacted eugenic sterilization laws, she learned, but North Carolina carried out the third-highest number of sterilizations in the nation, after California and Virginia. While most states pulled back from their programs after the atrocities of Nazi Germany laid bare the ethical flaws of eugenics theory, North Carolina accelerated its campaign, conducting more than 70 percent of all sterilizations after 1945. More than 2,000 sterilization victims were under 18, the youngest being a 10-year-old boy, and procedures often occurred against the will of victims and their parents.

In the latter years of the campaign, 60 percent of those sterilized were Black and 99 percent were female, leading a recent Duke University study to conclude that the state worked to systematically “breed out” Black people through its eugenics program during the late 1950s and ’60s.

That North Carolina’s K-12 schools have almost without exception ignored the state’s past practice of forced sterilization offers a compelling example of the suppression of racially motivated, government-inflicted harm long before the nation began debating critical race theory or states started passing laws restricting such teaching.

“It really kind of upset me when I found out about it, because I was like, ‘This is something that is such a major part of not only North Carolina history, but U.S. history, and it’s just something that had never been mentioned to me,’” Sharkey told The 74. “Some of these things were so close to home.”

None of her friends had any idea of their state’s history of eugenics, either. She would tell peers about what she was learning, only to receive shocked and horrified reactions. Even her mother’s parents, who lived in North Carolina while the program was active, were unaware.

“[It] left me feeling a little bit like I was being rigged of some information,” said Sharkey. “Like it was being hidden.”

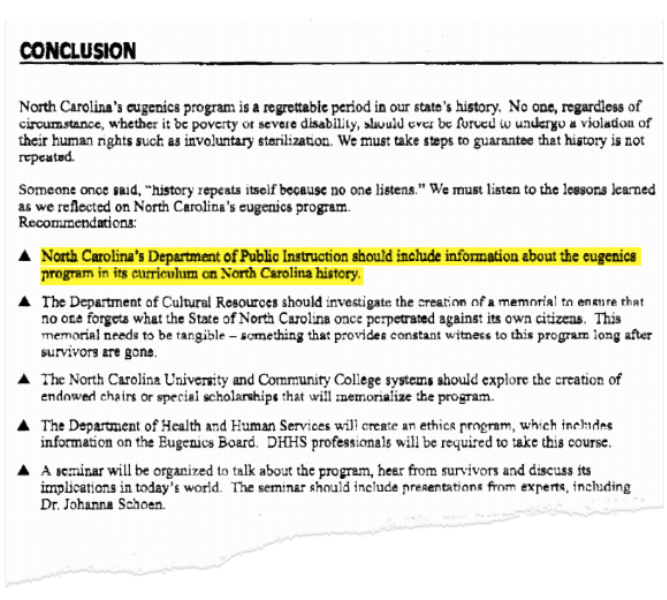

Intentionally or not, North Carolina has largely failed to deliver on efforts to use public education as a tool to reckon with its history of eugenics, despite a nearly two-decades old recommendation from a committee convened by former Gov. Michael Easley that called on the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction to “include information about the eugenics program in its curriculum on North Carolina history.”

Deanna Townsend-Smith, director of policy and operations for the state Board of Education, told The 74 that she was not aware of the board ever having heard or considered the task force’s recommendation. In an email to The 74, John B. Buxton, senior education advisor to former Gov. Easley, explained that because there was never a legislative requirement for the board to act, “that likely undercut the momentum for including content in the curriculum guidance documents.”

With the benefit of hindsight, June Atkinson, who served as state superintendent from 2005 to 2017, acknowledged that the Department of Public Instruction did not do enough to move the ball forward on teaching the state’s history of eugenics during her tenure.

“I believe we could have done some more about helping teachers incorporate eugenics as part of their curriculum by having more curriculum guides or more resources for them,” she told The 74.

While the current state history standards do mention the word “eugenics,” the reference is to the wider American eugenics movement rather than North Carolina’s program — and even that serves as an optional, non-mandatory example. The state’s U.S. history standards were recently given an “F” grade in a state-by-state review conducted by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a right-leaning think tank.

The 74 reached out to the state’s 10 largest school districts and none indicated that they include their state’s eugenics program in their social studies curricula. One district, Cabarrus County Public Schools, told The 74 that a single school has an elective course that covers the topic. Its unit on eugenics is called “Wicked Silence: The North Carolina Forced Sterilization Program and Bioethics.” Another district, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Public Schools, said that they provide optional resources on the topic that teachers may use in class. No other districts said that their schools directly reference the state’s eugenics program in curricular materials.

Basically, “there’s nothing stopping a teacher [from covering the North Carolina eugenics program] … but there’s also nothing requiring it,” Wake County Public Schools Communications Director Lisa Luten explained to The 74.

That’s in contrast with states like Virginia, where specifics on the state’s eugenics program are considered “essential knowledge” in statewide standards, according to information provided by the Virginia Department of Education. Or Oregon, where the Department of Education told The 74 that in-progress revisions to social studies standards will include the state’s history of eugenics as an example within a content area that examines structural disadvantages against people with disabilities.

It appears unlikely that North Carolina students will be learning anytime soon about the same disturbing history that, as Sharkey put it, was “going on in my own backyard.” That’s because conservatives across the country are taking aim are restricting “divisive” topics in the classroom through state-level bans on critical race theory, a previously arcane academic topic, and North Carolina’s state Superintendent Catherine Truitt last month forced a sudden revision to a years-long update of the state’s social studies curriculum over concerns that the new version focused too much on the perspectives of Black people.

Having trouble filling out the survey, go here tinyurl.com/nceugenicssurvey

‘An ugly, dark side of our history that needs to be shared’

By other measures, however, North Carolina was a nationwide leader in reckoning with its eugenics past. When a five-part series published in 2002 by the Winston-Salem Journal brought to light details of the state’s sterilization program that had previously been hidden in sealed records, the state took swift action. Then-Gov. Easley issued an apology and convened a committee tasked with leading the state’s reparations and healing process.

After more than a decade of persistent advocacy from late state Rep. Larry Womble, and with help from Republican ally Thom Tillis, who became the state’s speaker of the house in 2011, North Carolina in 2014 became the first state to send checks to sterilization victims as financial compensation for the injustices they endured. That action paved the way for Virginia and California to do the same in 2015 and July 2021, respectively.

In its response, the state also called for the creation of an exhibit “to ensure that no one will forget what the State of North Carolina once perpetrated upon its own citizens.” That task fell to Hodges, who heard stories as a child of her late aunt being among those victimized citizens and who was working at the state’s Office for Minority Health and Health Disparities at the time.

When the display was completed, visitors could inspect not only timelines and maps documenting the history, she said, but also copies of official records and the actual medical instruments that doctors used to perform sterilizations. One wall showed pictures of victims along with headsets. “You could pick up a headphone, and listen to the actual survivors in their voice,” recalled Hodges.

Yet after being created in 2007 and traveling to a handful of colleges and universities in the state, the exhibit was soon taken out of commission due to lack of funds in 2009, Hodges said. In 2011, it was put into storage in a vault operated by the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, where the department’s public information officer Michele Walker confirmed it is kept to this day. Audio elements of the exhibit are out of date, and the information included is not updated with the state’s compensation of victims, according to State Archivist Sarah Koonts. Certain loaned artifacts were also returned, she said.

Hodges never understood why the exhibit — created to make sure North Carolinians never forgot and then itself forgotten — was stored away rather than updated.

“It’s just sitting in a basement,” she said. “It’s a waste. Because it’s such an ugly, dark side of our history that needs to be shared.”

A ‘complex subject’

Despite North Carolina’s trailblazing campaign to compensate some of the victims of its eugenics program, Charmaine Fuller Cooper, who led the N.C. Justice for Sterilization Victims Foundation through 2012, worries that the lack of public education could jeopardize the state’s progress toward reckoning with its past.

“Education is critical to the effort,” she told The 74. “Unfortunately, it’s one of those things that still too many people are not familiar with.”

“To the victims and families of this regrettable episode in North Carolina’s past, I extend my sincere apologies and want to assure them that we will not forget what they have endured.”

—Former Gov. Michael Easley, April 2003

That squares with what Marion Quirici, a lecturing fellow at Duke University, sees in her disability studies classes, where she takes first-years to the library for primary source sessions on eugenics. While rarely discussed in current-day American classrooms, a belief in eugenics shaped U.S. education through much of the early 20th century, particularly in celebrating I.Q. tests as a way to weed out “feeblemindedness,” and providing the genesis for divisions between “gifted and talented” and “slow” courses of study.

“Students from North Carolina in particular always express shock at their own state’s especially egregious role in this history,” Quirici told The 74 in an email. “They’ll say, ‘I’m from here; I can’t believe I never learned this!’”

The stakes are high, says Barbara Pullen-Smith, former founding director of the Office for Minority Health and Health Disparities.

“If our young people don’t understand our history, we are certainly doomed to repeat it,” she told The 74.

In a twist of brutal irony, a figure who once propelled forward the effort to compensate North Carolina sterilization victims now stands in the way of students learning about eugenics and other dark moments of our nation’s history.

U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis, who as speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives played a key role in passing the 2012 legislation to disburse funds to sterilization survivors, in June co-sponsored the ‘Saving American History Act’ to defund any K-12 school teaching The 1619 Project curriculum. The 1619 Project is a Pulitzer Prize-winning effort from the New York Times Magazine that traces how systemic racism and the legacy of slavery impact America today, including eugenics-adjacent topics such as the infamous Tuskegee Study of Black men who were secretly denied treatment for syphilis under the guise of free health care. Its creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, recently turned down a journalism chair at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill after the school originally denied her tenure amid a wealthy conservative donor’s concerns over her work that many supporters viewed as racist.

Regarding how eugenics should be taught in the classroom, Sen. Tillis expressed mixed feelings.

“This is a very important, dark chapter in our nation’s history,” he told The 74. “It’s a complex subject that needs to be taught, but it needs to be taught at an age-appropriate level.”

When asked whether the North Carolina eugenics program’s absence in history standards and curricula presented a problem, he turned down the chance to comment.

Acknowledging his own opposition to the 1619 Project, Sen Tillis recommended instead convening a team of “academics and historians [with] some sort of an ideological balance for the preparation of curriculum so that you give these young people facts upon which they can draw their own conclusions.”

Teaching the ‘fractures’ in American democracy

Educator Matthew Scialdone, who taught Sharkley’s ‘Hard History and Civic Engagement’ elective at Middle Creek High School this spring, worries that the momentum — both local and national — against teaching about race could dissuade some educators from tackling difficult topics like eugenic sterilization.

“Given all of the pushback,” said Scialdone, “[eugenics] would probably be one of those topics that a teacher might back away from and say, ‘You know what, is it really worth stirring up whatever community uproar may come from me talking about this topic?’”

That’s unfortunate, says Dimitry Anselme, executive program director of the nonprofit Facing History and Ourselves, which creates online resources to help teachers effectively address the darker points of America’s past. There’s much to learn from difficult moments in history, Anselme says.

“For healthy democracies, you have to see the fractures,” he told The 74. “The fractures can teach us … what to seek to avoid and not repeat.”

The fact that eugenics laws were eventually repealed “actually speaks to what’s beautiful about democracy,” said Anselme.

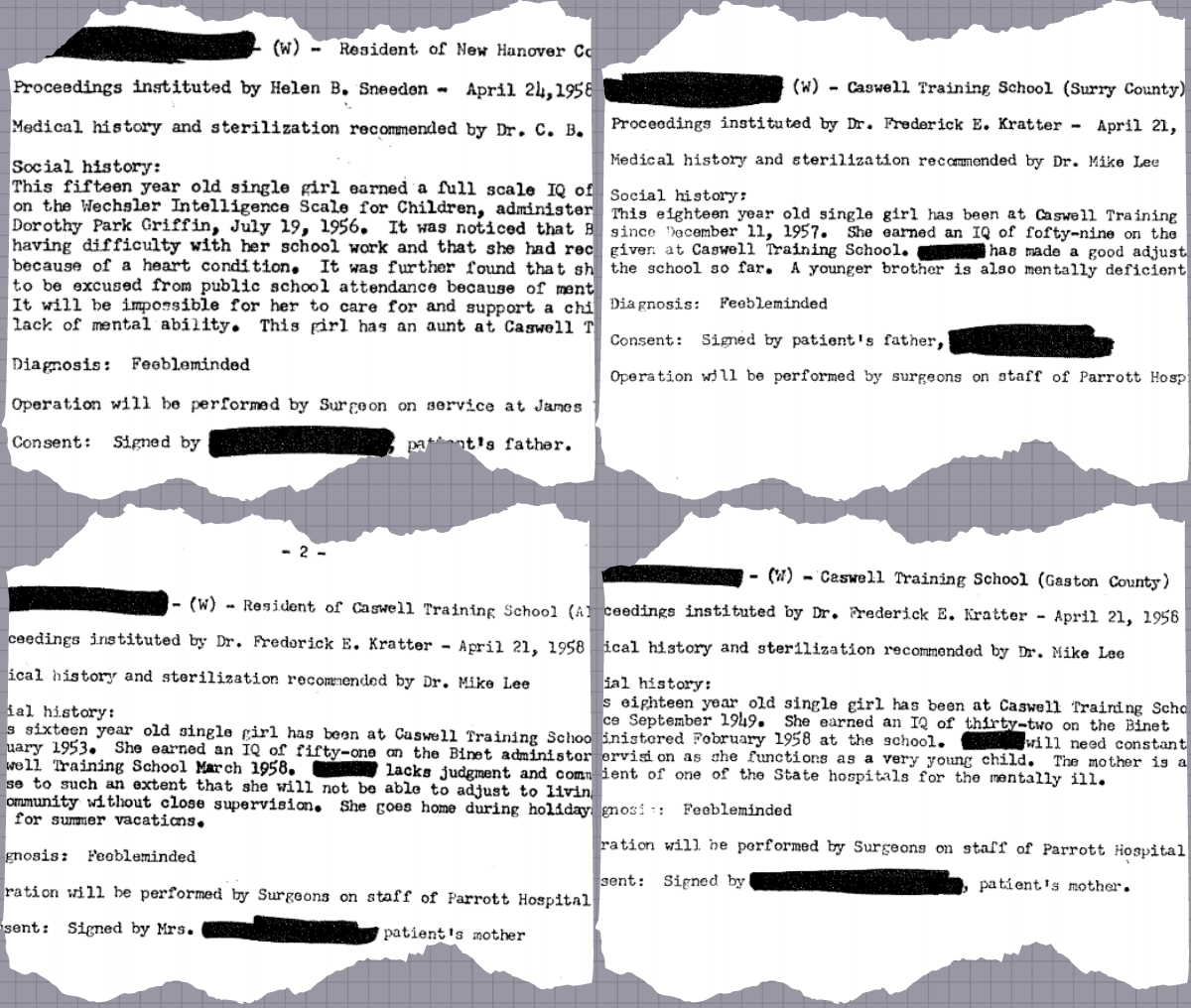

Scialdone emphasizes to fellow educators that there’s more than enough content available on the North Carolina eugenics program to engage students without worries over bias. The key in his classroom? Primary sources, says the 2015-16 Wake County Public Schools Teacher of the Year.

This spring, he presented students with testimony from survivors and medical records from the state archives that documented the paper trail of one young woman’s sterilization procedure.

“This isn’t somebody else’s interpretation that I’m putting in front of you. This is the real thing,” he told his class.

The impression on his students, many of whom were participating over Zoom, was immediate.

“The chat in that class just stayed scrolling,” remembers Scialdone. “There was a lot of OMGs. There was a lot of ‘wait what?’”

The content drew Sharkey and her classmates in. “I was so beyond engaged in this course,” she remembers.

But Scialdone knows that his class is the exception, not the rule. Teachers’ “default mode,” he knows, is to “teach what they were taught and how they were taught,” which means that North Carolina’s history of eugenics is “not really covered,” he said.

That’s a problem, he believes — for students and the state, alike.

“If I’m the only one doing it,” Scialdone said, “then the moment was lost.”

Educators interested in covering the history of North Carolina’s eugenics program may find curricular resources here and here.

Lead Image: Proceedings of the Eugenics Board special meeting May 19, 1958 (Courtesy of Johanna Schoen / Video by The 74’s Meghan Gallagher)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter