The 12 Best Education Articles From June: How Classroom Inequality Could Worsen During Coronavirus, Senators Push for More School Aid, Student Activists Join the Protests & More

Every month, we round up our most popular and buzzed-about articles from the past four weeks. (Go deeper: See our top highlights from May, April and March right here)

Amid the ongoing chaos of the pandemic and mounting warnings that the coronavirus will likely disrupt students’ trajectories for a second school year, June was also the month that found the nation mourning the death of George Floyd — and that student activists took to the streets to protest systemic racism in the police force and across the criminal justice system. It was these two storylines that dominated our early summer coverage, in addition to our notable profiles of schools in Los Angeles, safety policies in New York and policymakers in Washington, D.C.

Our 12 most-shared articles from the month are below. Follow our ongoing coverage of the pandemic, school reopenings and concerns about student learning loss at The74Million.org/PANDEMIC; you can also get alerts about our latest exclusives and analysis by signing up for The 74 Newsletter.

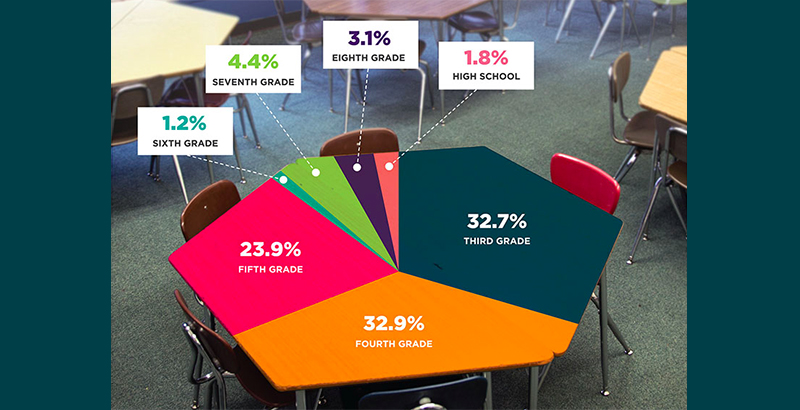

Equity: In the days immediately following the pandemic-related closure of schools throughout the country, researchers at the nonprofit assessment organization NWEA predicted that whatever school looks like in the fall, students will start the year with significant gaps. Now, they are warning that the already wide array of student achievement present in individual classrooms in a normal year is likely to swell dramatically. In 2016, researchers at NWEA and four universities determined that on average, the range of academic abilities within a single classroom spans five to seven grades, with one-fourth on grade level in math and just 14 percent in reading. “All of this is in a typical year,” one of the researchers, Texas A&M University professor Karen Rambo-Hernandez, told Beth Hawkins. “Next year is not going to look like a typical year.” (Read the full article)

Policy: Educators and parents have collaborated to find innovative approaches to meet the needs of all students during this pandemic, and districts have been creative and persistent in addressing student needs during the crisis, from access to high-speed internet to nutrition. But in a new essay, Sens. Maggie Hassan and Chris Murphy write that it’s clear more support is needed as we prepare to navigate educating our children through the fall — and that many of the students most in need of additional help right now also have disabilities, requiring extra assistance to access the same educational opportunities as their peers. That’s why the two are urging Senate leadership to ensure that any future COVID-19 relief package provides significant additional funding for school districts, including $11 billion in dedicated funding to aid states in appropriately meeting the needs of students with disabilities. “We’ve already seen bipartisan support for this initiative,” they note, “so we are hopeful that leaders in both parties will see its value. We will also be introducing legislation in the coming weeks to put these funding levels into action and reaffirm that every student has the right to a free and appropriate public education.” (Read the full essay)

A Border School for Asylum Seekers Goes Virtual

Immigration: For the close to 2,500 asylum seekers in the tent city in Matamoros, Mexico, life has gone from hardship to hardship. They have escaped gangs and oppressive regimes but now face the regular threat of floods, kidnapping and a strict “remain in Mexico” policy set by the Trump administration. Until 2019, the camp’s children had few options but to pass their days near the foot of the Gateway International Bridge, playing with rocks and dirt or sitting idly through what should have been a day inside a classroom. That changed when two American volunteers opened The Sidewalk School, just 3 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. Since then, the school has grown to a staff of 11 teachers, with 235 students ranging in age from 1 to 16. Now, it faces a new challenge: educating during a pandemic. With $20,000 in its coffers, the school bought tablets and decided to go virtual. But it has also maintained a presence inside the camp, implementing health and safety guidelines that schools around the world are only just now developing. “I don’t think people understand what an encampment is, how small it is, how people live in the woods, one on top of the other,” said school co-founder Felicia Rangel-Samponaro. “Social distancing cannot happen.” (Read the full story)

Activism: College student Dekaila Wilson led chants in NYC’s Union Square that left her voice hoarse the next day. San Antonio teen Kayla Price joined a rally of 5,000 protesters. D.C. student Jordyn Middleton, unable to protest, held up signs in a car line and is helping guide the conversation online. They’re among the countless young people across the country who have been swept up in an extraordinary push for social change following the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, in police custody in May. Protests like the ones that have sprung up across more than 100 cities are not new, but they’re playing out against an unprecedented backdrop: a global pandemic that’s underscored existing inequities, disproportionately wreaked havoc on the health and livelihoods of communities of color and shut down America’s K-12 and higher education systems. Students say they’re frustrated and tired of still having this fight. But they’re also hopeful, energized by their collective power in this moment. “Something big is going on here,” Wilson said. “This is a revolution.” (Read the full report)

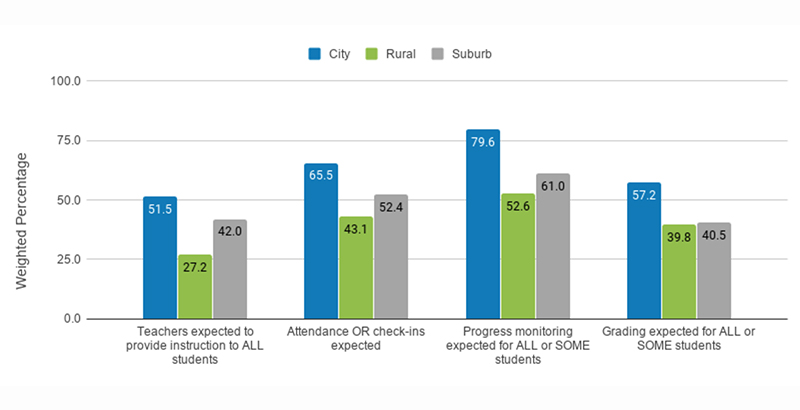

Analysis: The Center on Reinventing Public Education recently released an analysis of 477 school districts, for the first time comparing districts by student demographics and location. The results, write contributors Robin Lake, Betheny Gross and Alice Opalka, are sobering. Just 1 in 3 districts has been expecting all teachers to deliver instruction — and rural and small-town districts were far less likely than urban and suburban districts to communicate that expectation. Districts with the most affluent students were twice as likely as those with the highest concentrations of low-income students to require at least some teachers to provide live, real-time instruction. While many teachers have gone above and beyond their districts’ requirements, by not setting clear expectations that teachers would teach and students would learn, “Far too many districts left teachers on their own to figure out remote learning in the spring, and may soon squander the opportunity to make up lost academic ground this summer. This should trigger alarm bells about the learning gaps students will likely face when they return to school this fall. … School system leaders must not leave teachers on their own to navigate an unprecedented set of education challenges a second time.” (Read the full report)

Research: As districts cut ties with police departments amid weeks of nationwide protests, new research finds an unsettling racial gap in the way campus officers perceive threats. In a predominantly white and affluent suburban community, school resource officers worried most about intruders. Yet in an urban district where students of color made up half the population, police perceived students as the primary threat. Racial stereotypes likely shape how school-based offers perceive threats on campus, according to the first-of-its-kind, forthcoming study. But the report’s lead author, Ben Fisher of the University of Louisville, said the issue could be far more systemic than a few “bad apples” and could be “baked into the system.” Though the officers didn’t comment on their schools’ racial demographics directly, they frequently relied on what the researchers called “racialized tropes” to describe the students in their schools. Because officers in the urban community described student threats “as a certainty, not a possibility,” their perceptions could “expose students of color to more frequent and intense police interactions,” according to the report. (Read the full article)

First Person: In the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police, decades of pain gave way to racial unrest that have reduced parts of the city and neighboring communities to cinders. The fire at Gordon Parks High School wasn’t the most destructive, but it was among the most symbolic: The school is named for a photographer who spent decades bringing the poverty and despair that gave rise to race riots of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s to the attention of white America. Beth Hawkins grew up not far away, and as she watched communities respond to the terrifying events in her hometown, schools — Gordon Parks and her own family’s — were on her mind. (Read the full essay)

Early Education: Catherine Lieberman has been co-owner and director of Bell’s School for People Under Six in Fletcher, North Carolina, for 42 years. Since the pandemic, “I’ve lost over half my business,” she said during a May 28 virtual event for preschool providers. “I haven’t taken a paycheck since March 16 because I don’t think I can take one when I can’t afford to pay my staff. I’ve had to lay off 11 of my 13 employees in order to stay open. I’m struggling to pay the mortgage, the lights, to keep the water running and pay for the cleaning supplies I need just to stay open. It’s a financial impact, but it’s an emotional impact as well.” That emotional — and educational — impact is also being felt by families across the country, as they confront deep uncertainty about whether and where their young children will return to day care and preschool and how they are going to make that work with their jobs. Jennifer Geller says her 4-year-old daughter Sadie “misses having teachers and kids and a full day of activities and learning. She’s gone from that to too much time on the iPad.” Geller is hoping Sadie’s Manhattan preschool will reopen or that she can get into her first choice in the city’s public pre-K program. (Read the full article)

Commentary: The killing of George Floyd and subsequent calls to action by the Black Lives Matter movement drove home some long-ago lessons for contributor Derrell Bradford about the continuum on which race, the police and education interact. “If you think about race and education and policing as intertwined, there is also no moment when you do not see how they conspire for the betterment or detriment of the country’s children; and, for much of my adult life, the country’s Black children. … And at this moment, the overlap could not be clearer. … You cannot solve a problem of Black lives with an all-lives solution. … We can’t have an ‘all education matters’ approach to the challenges of Black education. One that doesn’t require states or districts to meet the needs of kids who, too, are fighting to be free and equal, but instead demands they conform to systems that have not historically worked for them in the name of the public good. All education cannot matter until Black education does. … As the only people in this nation’s history who have been both physically enslaved and intellectually starved as a result of not just sentiment, or economics, but public policy, no solution that requires the sacrifice of Black people to be successful will be a solution that works for Black people. … The story of Black people is the story of our country’s efforts to live up to its founding values. Black lives matter, and Black education matters, because everyone’s freedom matters. And only when Black folks are safe to both learn, and live, will all Americans be free.” (Read the full essay)

74 Interview: D.C. Public Schools’ 2019-20 academic year ended May 29 as social unrest and a continuing global pandemic gripped the capital and country. So Chancellor Lewis Ferebee is determined that come fall, schools will remain a stabilizing force for students. “Our presence, purpose and commitment” are a constant, he said last week, and he hopes to get students back to full in-person instruction when the 2020-21 school year begins Aug. 31 — though he acknowledges the decision hinges on parent feedback and health officials’ guidance. The district is facing other hurdles, too: how to “creatively” test for learning loss, how to ensure internet access for all students and how to meet the ballooning mental health needs of educators and students. But a rare increase in per-pupil funding, a “summer bridge” program and mentoring for graduating high schoolers should help. (Read the full interview)

Investigation: Under oath in a sterile, wood-paneled courtroom, a Long Island schools superintendent implored a judge to prevent every educator’s worst nightmare: Barring immediate action, she testified, one of her students could become the next school shooter. She asked the judge to use the state’s new “red flag” law after the student uploaded a social media post threatening to “kill everyone.” The law allows judges to confiscate guns — or restrict access to them — from people they believe may harm themselves or others. Roughly a third of states now have such laws, most of which were enacted after the 2018 mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida. But New York’s law goes a step further: It is the first to give educators the right to petition the courts directly — something typically reserved for police and family members. (Read the full article)

Profile: Traditionally, special education is a place — a room or a collection of them — where children with disabilities are sent to receive services meted out in minutes. Expectations and success rates are rock bottom, and students rarely get the most challenging lessons of art, music and other opportunities for enrichment, engagement and building social skills. Meanwhile, their regular classroom teacher, if they have one, has little idea what their disability supports look like. But Southern California’s CHIME Institute Schwarzenegger Community School, created to prove that all kids can thrive in the same classroom, practices “full inclusion” — meaning no one is pulled out and sent anywhere. Gifted kids, children with Down syndrome, children who communicate through assistive technology and their typically developing brothers and sisters work together, on the same lessons and with the same teachers. A steady stream of visitors is introduced to strategies that can be translated to mainstream settings — and to the radical idea that all students benefit from them. In this school profile written pre-pandemic, Beth Hawkins unpacks what makes CHIME a national model. (Read the full article)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)