Analysis: Just 1 in 3 Districts Required Teachers to Deliver Instruction This Spring. They Mustn’t Be Left on Their Own Again in the Fall

Researchers at the Center on Reinventing Public Education spent this spring analyzing 82 school districts’ responses to COVID-19 closures.

Our analysis focused on large, high-profile school systems. While the districts served more than 9 million students combined, we wondered if it represented school systems across the country.

Now, we know the picture it painted was too rosy.

We recently released an analysis of a statistically representative sample of 477 school districts. This allows us, for the first time, to compare districts by student demographics and location. And the results are sobering.

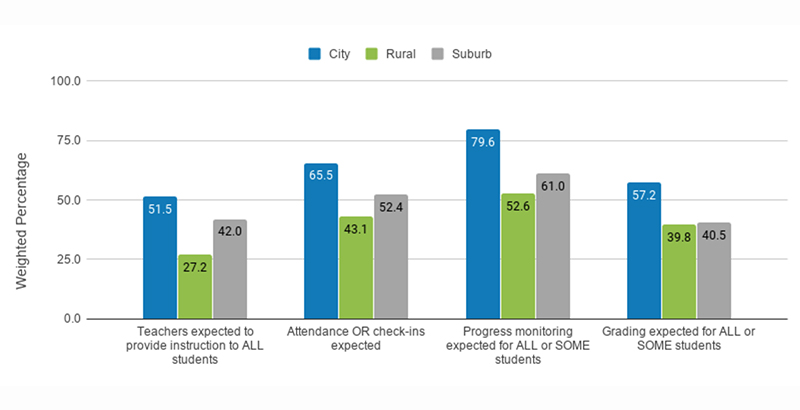

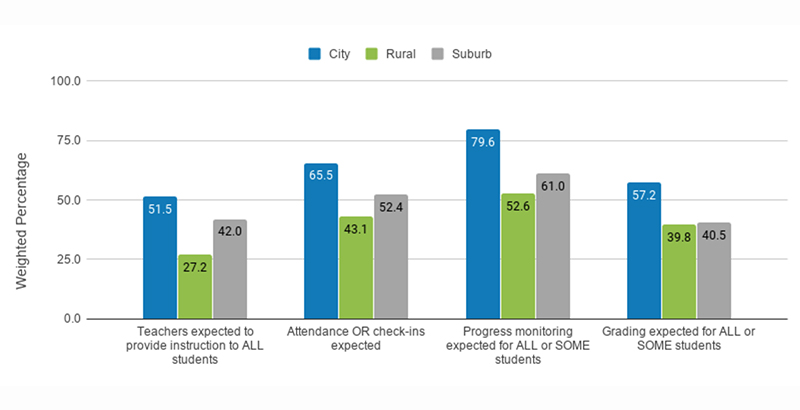

Just 1 in 3 districts has been expecting all teachers to deliver instruction — and rural and small-town districts were far less likely than urban and suburban districts to communicate that expectation.

Districts with the most affluent students were twice as likely as the districts with the highest concentrations of low-income students to require at least some teachers to provide live, real-time instruction.

Less than half of all districts communicated an expectation that teachers would take attendance or check in with students regularly.

We know that many teachers have gone above and beyond their districts’ requirements. Some stayed in touch with their students or offered feedback on their work even though their district didn’t mandate it.

Still, by not setting clear expectations that teachers would teach and students would learn, the majority of school districts left teachers on their own to figure out what they needed to do for students, and how.

We know some students might not have a reliable internet connection. Others might not have computers at home, or need to share one device with multiple siblings, or work alongside brothers and sisters in a one-bedroom apartment.

Our analysis suggests that a large number of school districts across America responded to these challenges by catering to the lowest common denominator. They distributed paper work packets — one method that could easily reach everyone but undoubtedly left many students bored or unsupported.

Other districts set higher expectations while acknowledging that reaching some of their students would require extra effort. Their plans called for teachers to work to keep learning going to the greatest extent possible. They embraced a problem-solving ethos. They kept looking for new ways to reach students and supported learning in multiple formats in hopes that none slipped through the cracks.

For example, New London Public Schools, a small district in Connecticut, serves a majority-Hispanic population, 85 percent of whom qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. All students received an iPad or Chromebook in late March, which enabled teachers to provide remote instruction and monitor students’ academic progress. For elementary students, the district used SeeSaw to assign lessons and share recorded videos. In grades 6-12, teachers used Zoom to deliver lessons, supplemented with assignments in Edgenuity.

While the district expects students to complete assignments, it is also providing summer school to help those who did not fully engage with remote learning this spring to start catching up before next school year — an opportunity we know many districts are missing.

On the Spirit Lake Reservation in central North Dakota, Fort Totten Public Schools provided devices to all students who needed them, but the district also knew that many families didn’t have access to high-speed internet due to the rural and remote location.

The district chose an online learning platform for instruction that could operate on lower bandwidth, offered Wi-Fi in school parking lots and supplemented this with paper packets for students who couldn’t access any of these options. But to ensure continuity and personal connection for every student, teachers were instructed to contact their students daily and to use the form of communication that was accessible to that student.

Far too many districts left teachers on their own to figure out remote learning in the spring, and they may soon squander the opportunity to make up lost academic ground this summer.

This should trigger alarm bells about the learning gaps students will likely face when they return to school this fall. The challenge of reaching at least some students and teachers remotely likely isn’t going away. Some students will need different supports to make up for the learning they missed this spring.

School system leaders must not leave teachers on their own to navigate an unprecedented set of education challenges a second time.

Robin Lake is director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. You can find her on Twitter @RbnLake.

Betheny Gross is a senior research analyst and research director at the Center on Reinventing Public Education and affiliate faculty at the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington Bothell. She coordinates CRPE’s quantitative research initiatives, including analysis of portfolio districts, charter schools and emerging teacher evaluation policies.

Alice Opalka is a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, where she works on projects related to portfolio strategy, cross-sector collaboration, system governance and more. Before joining CRPE, Alice was an Education Pioneers Fellow in Los Angeles, an AmeriCorps volunteer coordinator at a children’s literacy organization in Los Angeles and a college access mentor with College Access Now in Seattle.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)