‘My Terrestrial Mission’: Black Astronaut Bernard Harris on Boosting STEM Access for Underserved Students

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

See previous 74 Interviews: Colorado Springs schools chief Michael Thomas on being a Black leader working to change a white system, 16-year-old “Jay Jay” Patton on making coding accessible to girls of color and researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings on culturally responsive teaching. The full archive is here.

As a child, Bernard Harris was a self-described “geek,” thrilled by science fiction.

In 1969, he watched with awe as Neil Armstrong took his “giant leap for mankind” onto the surface of the moon. For Harris, it was also “a tremendous leap for this little kid,” he said, “this little Black kid.”

The event inspired him to pursue a career in medicine as a pathway to becoming an astronaut. He excelled in high school, college and medical school, even as controversies over desegregation disrupted many campuses in his home state of Texas.

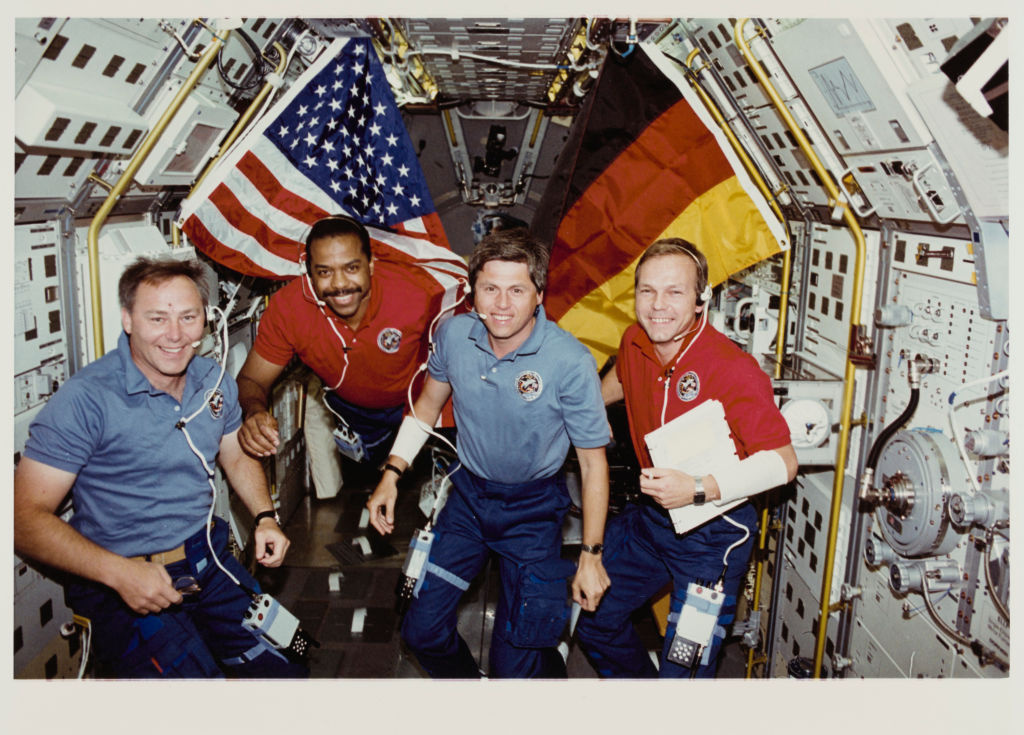

Nearly 25 years after the NASA moon landing ignited his passion for space travel, Harris achieved his longtime goal, embarking on his first space mission in 1993 and flying over 4 million miles in space. Two years later, in 1995, he became the first Black American to walk in space, spending 6 hours in orbit outside the spacecraft.

Now he’s on a new mission — what he calls his “terrestrial mission” — to ensure that all students have access to high-quality STEM education. The retired astronaut serves as the CEO of the National Math and Science Initiative, which works with students and teachers across the country to advance learning in those disciplines.

With researchers estimating that pandemic disruptions caused U.S. students, on average, to fall five months behind in math last school year, The 74 spoke with Harris about how to inspire students to bounce back and succeed in STEM fields. (Plus some bonus questions about what it’s like to be in space — we couldn’t help ourselves.)

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The 74: What inspired you to become an astronaut? And what was the pathway that got you there?

Bernard Harris: My inspiration began when I was 13 years old watching the [NASA] space program. I’ve been a geek for a long time. So I love science and science fiction and particularly space science. So I followed the early space program, you know, as many kids did at my age.

In 1969, when Apollo 11 landed on the moon, I watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. And when they said, ‘One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,’ it was a tremendous leap for this little kid. And I should add, this little kid of color, this little Black kid would look at that black and white television and say, ‘Hey, I want to follow these guys’ footsteps.’ And that’s really how it began.

I also remember, I think it was in the beginning of high school, writing a letter to NASA and saying, ‘I would like to be an astronaut, what do I need to do?’ And so they sent back this list of requirements. One of them was to have an advanced degree in a STEM field. So I started looking at careers that could lead me to NASA. One of those was aerospace engineering and the other one was medicine. And the medicine stuck.

You’ve traveled over 7 million miles in space. What’s that like? And also, what did it mean to you to be the first Black American to complete a spacewalk?

I flew on two missions. The first one was Columbia and the second was Discovery. My first mission was about two weeks, and my second one was nine days. … [In the space shuttle,] we’re able to go from zero to 17,500 miles an hour, and reach an initial altitude around 200 miles in about eight and a half minutes. So it’s a very exciting ride. You’re being pushed back in your seat to three-and-a-half times your weight and you go from that to zero gravity in just a split second when the main engines cut off. Then you know you’re in orbit.

I was lucky enough to [don an extravehicular activity suit and step outside the spacecraft] on my second mission, and spent just under six hours in orbit. … I could look inside and see my fellow crew members, as we all went around the earth at 17,500 miles an hour. That allows us to go around every 90 minutes and see a sunset or sunrise every 45 minutes. So it’s pretty awesome.

Having that view from space … it is a uniting experience to realize that, you know, as big as we think the Earth is, it really is a tiny thing amongst the vastness of not only our solar system and our galaxy, but the universe in which we reside.

That sounds incredible. Do you want to say a few more words about what it meant to you to be the first Black American to do a spacewalk?

It’s not something that I set out to do, it just happened. It had been 30 years since Ed White did the first spacewalk [before] a person of color, particularly Black, had had a chance to do a spacewalk. So that’s a long period of time.

I did feel that I had a lot riding on my shoulders … to help those who may not think that we as Black people can do those things (like space travel and space flight) to say, ‘Hey, we can.’ And not only can we do those things, but we can in many cases do them better.

It’s about breaking the ceiling, it’s about providing a different perspective so when people think about spaceflight, they just don’t think about white guys going into space, or white guys doing a spacewalk. They can see people of color, they can see women that are equal participants in the next frontier, which is spaceflight. And I felt very proud to be part of that moment.

It’s hard to think of a career more thrilling than astronaut. So why then pivot to STEM education?

I like to describe it as my terrestrial mission. My extraterrestrial mission was to go into space. … Now, I want to make sure that any person, no matter what skin color [or] ethnicity that wants to have that same experience can do it.

We’re in the 21st century where technology drives everything that we do. And I want to ensure that all of our communities have the opportunity to participate in this world equally. Because we all have the same ambitions, ideas, motives and needs. I want to make sure that there is high-quality STEM education that’s being delivered to all of our communities no matter who you are. … So my new mission, which includes the National Math and Science Initiative, is to make sure that we have high-quality STEM education that is delivered no matter where the students are.

Can you tell us more about the National Math and Science Initiative’s model? How does it work?

Yeah. So the National Math and Science Initiative has been around almost 14 years now. We have what I call four legs of the stool:

We have what we call the College Readiness Program, which is basically Advanced Placement. And so we’re one of the larger providers with Advanced Placement education in the country. Over 2 million students have gone through that program.

Our second program is called Laying the Foundation. And this is where we provide STEM education to educators, so professional development to make sure that they have the expertise, and content delivering STEM education. Our idea here is to make sure that teachers can teach effectively to the students. … Over 65,000 teachers have been educated through that program and growing.

Our third program is called UTeach. We have a partnership with the University of Texas where we create a program that takes students who are majoring in STEM, add some additional coursework and now they’re able to leave with their STEM degree and the ability to teach. So that’s part of our teaching preparation pipeline.

And our fourth leg is one that was accelerated by COVID, and that is to take our programs and deliver them virtually. We have online training for both teachers and students in STEM and so we now as an organization have the capability of doing what we call blended learning. So we can do face-to-face or be able to give them access to our programming virtually.

You mentioned that it was watching the initial NASA space missions that lit your flame in science education. How do we light the flame for current students?

We light that flame by showing them what they can do. And I make that statement specifically for kids of color who, you know, may be watching television and see the stereotypes. We have to get past that. And one way in which you can get past that is to have people who look like you doing the things that you might not think were possible.

I spent a fair amount of my time in schools so that kids can see me as a Black astronaut, as a Black physician. There was a quote — it’s not mine — that ‘You can’t be what you can’t see.’ And it is important that we open that door for everyone.

Just personal background, I grew up poor. I came from a divorced family. My mom had a college education. My dad didn’t. And so one of the first lessons that I learned growing up was the fact that education gives you options. So part of my goal is to make sure that kids, no matter what their background, have options.

Researchers estimate that U.S. students, on average, fell about five months behind a typical year’s worth of learning in math last year with further gaps for the most disadvantaged. To catch students up, what are some successful techniques you’ve seen on the ground that give you hope or optimism?

So of course, I’d be remiss not to say that we are on the ground. That’s what we do. And a couple of programs I’d like to highlight [with which] we’ve done some partnership:

We have a program that we’re doing in Houston where we are working with colleges and with high schools, to prepare students in high school to become STEM teachers. There are a lot of school districts that don’t have enough teachers, especially STEM teachers. So we’re trying to fill that pipeline.

We have a program in Alabama in which we’re partnering with the state where we are providing our master teachers to support teachers in their existing schools. And Alabama, of course, they have a large rural population, but this can be applied anywhere. We’re taking this model to many other states.

I also want to bring up curriculum, because if you open a typical science or math textbook, most of the researchers described — from Newton to Einstein — are white men. But those narratives are incomplete. How can teachers widen whitewashed conceptions of who “does” science and math? Are there other historical figures teachers should highlight? And you’re allowed to include yourself.

Yeah, not only myself, but there are plenty of scientists and folks that are not famous, but should be. Now, I’ll name a couple of them. [Daniel Hale Williams] was the first physician, not just Black [physician], to do open heart surgery, but people don’t realize. You’ll find him in some historical texts, but not many, unfortunately. Another one is Benjamin Banneker. He was the architect who laid out Washington, D.C. There are hundreds of other scientists out there.

And one last thing I’ll say, is that for one of our programs, we invite our funders — we have funders like Exxon Mobil, Boeing and Toyota, for example — and they will give us their scientists and their engineers to go out and be mentors for kids. So these are not “famous” people, but they’re famous to those young people because we’re exposing them to people who look like them. And, you know, it’s not just Black people, it’s not just people of color, but women. They’re also part of this program. We call them rock stars of STEM. So we try to show kids that you don’t have to see these folks on TV to be inspired.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)