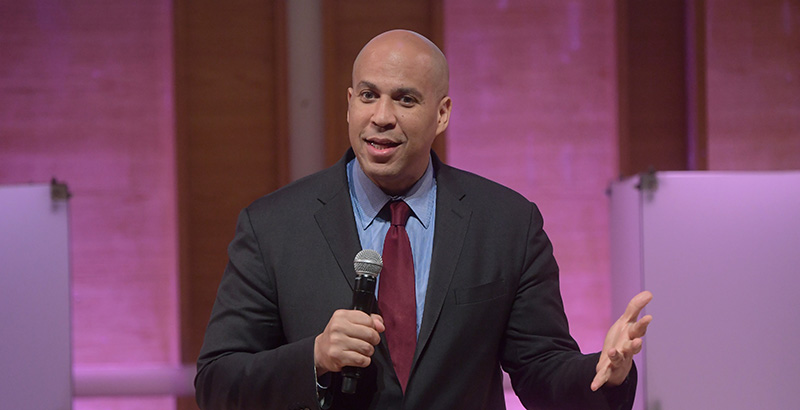

EXCLUSIVE: Senator Cory Booker Speaks Out About Newark School Reform, Equity, and Mark Zuckerberg’s Millions Ahead of a Possible Run for the Presidency

Earlier this year, after noticing that someone with a Senate email was looking at my LinkedIn page, I received an invitation from Sen. Cory Booker’s press secretary to talk about new research showing enormous progress in Newark schools, which he attributed to reforms implemented when Booker was mayor. I gathered up copies of the studies and drafted a few questions for a short January interview with a busy senator.

Rather than a quick question-and-answer session, the senator talked for nearly 90 minutes about his high-profile efforts to turn around Newark’s failing schools with a $100 million grant from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and its spectacular rollout on Oprah Winfrey’s TV show. He spoke about why he decided to tackle education reform and the difficult politics around reforming urban schools.

Frustrated by the negative coverage of the city that came out of Dale Russakoff’s 2015 book The Prize, he said Newark’s rising English and math test scores in grades 3-8, a shrinking achievement gap, and improved graduation rates — up nearly 20 percentage points since 2010 — prove that Newark’s reform efforts were very much a success.

He said he hoped these studies would help turn around the persistent negative narrative.

Though charter schools were a key component of Newark’s education turnaround, and Booker served on the board of a high-performing charter in the city, multiple commentators have noted that he, like many Democrats, has lately avoided talking about education reform issues, like vouchers and charters, to distance himself from President Donald Trump and U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. Those issues are not mentioned on his Senate website, and he has not served on the Senate education committee. Yet Booker spoke quite openly with me about his legacy in Newark, charter schools, and urban school reform, while touting the new research.

He talked at great length about equity in education (“Genius is equally distributed”), education and the economy (“The greatest economic development plan for any country is a great public education system”), school choice (“My loyalty is to a free, high-quality public school education … I don’t care if you’re a charter school. I don’t care if you’re a magnet school”), support for great teachers (“Incentivize great teachers to stay with higher pay”), innovation (“Focus resources on ideas that work, including ideas from teachers”), teachers’ salaries (“We massively underpay teachers in America”), and parental involvement (“Empower parents in the decision-making process”). You can read selected highlights from the transcript right here.

If, as rumors, public appearances, and a growing campaign war chest suggest, he is planning on running for president in 2020, Booker won’t be able to avoid hot-button education topics. And as much as he might like to put some space between himself and the Trump team, it will be difficult to avoid those topics in a presidential campaign. It’s not hard to imagine a question regarding his record on Newark schools being asked on a debate stage.

Defending that record, in an era of heightened party polarization, will be a tightrope dance for Booker — and, if his conversation with me is any indication, one he has already begun.

A city — and a school system — in crisis

When he first became mayor in 2006, Booker said, Newark was in the middle of a recession.

“I was mayor during the worst economy the city has ever seen. Our unemployment rates were at Depression-like levels. We inherited a city that was bankrupt already,” he said.

“From 2009 to 2012 were the most difficult governing years of my life, because the community was hurting so badly. People were being laid off from their regular jobs. We cut our government by 25 percent to keep this city on board. I tell my Republican colleagues now that there is nobody in the Senate who ever cut government as much as I did. Because we were forced to.”

To help keep housing in the city affordable and make up for lost revenue streams, Booker told me, he turned to philanthropy, raising money from celebrities like Winfrey and Jon Bon Jovi to help pay for housing for veterans, people with HIV/AIDS, and recovering addicts. They built acres of new parks and refurbished old ones. They provided incentives for building supermarkets in food deserts and brought in new businesses, like Panasonic, to the city.

The city “got winds in a recession,” he said, from the partnerships he formed with philanthropists. Those connections would later come into play for Newark’s schools.

Newark’s education system was in bad shape too. In 23 of the district’s 75 schools, fewer than one-third of children in grades 3-8 could read at grade level, Russakoff reported. While the city already had a number of well-established, highly effective charter schools, many district schools were so awful that “nobody would ever send their kids there who could have other choices,” he said. Classrooms were half-empty and the education ineffective; there were “bottom-quartile schools that were an affront to the genius of our children,” but city education officials told him there wasn’t the political will to make changes.

Desperate parents resorted to using fake addresses to sneak their children into nearby suburban school districts — which hired private investigators to follow them home. If caught, those students were kicked out.

“I would rather that my neighbors go to a great school and hate me, than love me and continue to go to a bad school.” —Cory Booker

Booker told me about the time he was standing outside a small private school that had been forced to close for financial reasons, and a parent grabbed him by his lapels and showed him a newspaper article that said 100 percent of students in the local public school had failed the state standardized test. “She felt like it was a death sentence sending her child to this school,” he said. It was shocking stories like this that forced him to consider major school reform.

Local activists and school leaders also nudged him to take a stronger role in education. He said Chris Cerf, the state superintendent for education, asked him, “Are you going to the mat for public school children?” Cerf’s question, Booker said, was “the kick in my tuchus that I really needed” to “leverage more change in the traditional district schools.”

So, toward the end of his first term, in late 2009 or early 2010, Booker told his staff he wanted to wade into school reform. “I said to Mo [Butler, then chief of staff], ‘Good news! I‘m going to take this on. I’m going to go out and raise $40 million, $50 million to try to leverage change.’”

His staffers, however, were adamantly opposed. Schools in Newark weren’t even under local control; the state had run the district since 1995 (the city regained control this past February). To make any real changes, Booker would need the support of Chris Christie, New Jersey’s Republican governor, who had not shown much interest in helping urban areas.

There were powerful political forces opposing him at the local level as well. As Butler explained, “Whenever you lay off 25 percent of your workforce, you create a lot of people who are very invested in destroying you.”

On top of that, the school district budget — at $1 billion, larger than the city budget itself — had historically been a source of political power and graft, gaining it the nickname “the prize” (that’s where Russakoff got the title for her book). With 7,000 people on the payroll, the district was the biggest public employer in a city of roughly 270,000. Newark schools were as much about employing adults as educating their children. With such a large, unwieldy, and politically charged public school system, reform wouldn’t be easy.

Few mayors have successfully reorganized their schools without jeopardizing their jobs. Booker pointed to the book The Bee Eater, by The 74 contributor Richard Whitmire, which describes how efforts to reform the Washington, D.C., schools ultimately destroyed the political career of Mayor Adrian Fenty. Booker was bemused by the fact that people voted Fenty out — but now love their schools.

Still, knowing all that, he wanted to dive in. “I said I would rather that my neighbors go to a great school and hate me, than love me and continue to go to a bad school.”

What Zuckerberg made possible

As he had done for his housing initiative, Booker turned to philanthropy.

Because the city had no legal oversight of the school system, he started with charter schools. During his first term, he raised tens of millions of dollars to start the Newark Charter School Fund, which helped to restructure the city’s charter sector. Poor schools were closed, middling ones were bolstered, and top-performing ones were expanded by removing political barriers and finding them facilities. Booker helped recruit highly effective teachers and principals for those schools as well. With a background as a board member of the North Star Academy charter school — now ranked 13th-best in the state — he said he was very familiar with how the good ones operated.

Booker said, “In my first term as mayor, we had incredible success with thousands of kids getting access to these great charter schools.” But he wanted broader reforms.

“So we decided to just take all of these chips that we were building up by building parks, getting supermarkets, and affordable housing. Even during this recession, our approval rating was close to 80 percent [in internal polling by his office]. So we just said, ‘Let’s take all of the chips and slide them on the table and go through the boldest sort of shock to the system as we possibly could get.’”

Around the summer of 2010, as Booker was reaching out to wealthy donors for philanthropic grants for various initiatives, he met Zuckerberg, and they began talking about funding a project for Newark schools.

“I met Mark and had some great conversations with him,” Booker said. “And Mark was … willing to help and was willing not to be prescriptive. He said, ‘What I believe is finding good leaders and giving them the ability to run with the ball.’”

Zuckerberg didn’t have any specific education agenda; Booker’s broad package of policies — which included expanding charter and magnet schools, closing the lowest-performing schools, changing school leaders, implementing a new curriculum aligned to the Common Core standards, renegotiating the teachers’ contract to allow merit bonuses for highly effective educators, and creating a universal choice plan that allowed parents to submit a single application for both district and charter schools — all sounded good to him. Said Booker, “He had pretty much already decided he was going to place his bet on us.”

To help double Zuckerberg’s $100 million pledge with matching funds, they reached out to Winfrey and urged Zuckerberg to go public with his donation, rather than giving the money anonymously, as he preferred. “After that, I could get my phone calls returned by everybody,” Booker said. He was able to raise even more money and garnered national attention that energized the community.

“Now every neighborhood, every community you go into, every barbershop, everybody was talking about Newark education, which I rejoiced in thinking, this is a great thing that children and children’s education are at the center of every conversation in Newark,” Booker said.

“The Prize”

But implementing school reform was a bumpy process, according to Russakoff’s book. The Prize describes turbulent school board meetings that pitted black and Latino parents and community leaders against white consultants and outside administrators, with their top-down management style. The eye-popping numbers that Russakoff cites — $21 million spent on thousand-dollar-per-day consultants, $89.2 million on labor contracts, $57.6 million on charter schools — grabbed headlines.

While Russakoff did not outright call the Newark school reforms a failure, most coverage of her book used words like “squandered,” “failed miserably,” and went awry” to refer to Zuckerberg’s donation and the reforms it helped pay for.

Newark school reform soon became synonymous with waste and failure. Just this month, an article published in Slate called basketball superstar LeBron James, who recently opened a district school in his hometown of Akron, Ohio, “the anti-Zuck.” That story characterized the Newark reforms as “famously troubled” and triggering “community backlash,” and it linked to a New Yorker article by Russakoff that was the precursor to her book.

Booker and his staff believe Russakoff misrepresented or misunderstood events and was swayed by an anti-school-reform perspective. They said she focused on the “political sausage-making” of the reforms rather than early signs of progress and that the book was written too early to tell what differences the changes were making.

Russakoff declined to comment for this story.

Patrick McGuinn, a professor of education and politics at Drew University in New Jersey, wondered whether anyone could have implemented such an ambitious reform plan without backlash, given Newark’s long history of contentious politics. “Anybody trying to improve Newark schools was going to have one heck of a time of it,” he said.

The studies

Although Booker said he bears no ill will toward Russakoff herself, the media response to her book resulted in a permanent negative brand for his reforms that made it difficult to change people’s minds, even with the new studies that back up his claims of success. Booker said, “It’s one of the biggest disconnects between reality and perception that I’ve ever seen in my politics.”

According to a report released this year by Newark Public Schools, graduation rates are up from 59 percent in 2010-11 to 78.3 percent in 2016-17. Low-income students, who make up 80 percent of the population in the city’s schools, outperformed peers in other states that administer the PARCC exam: Colorado, Rhode Island, Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, and Washington, D.C. The report also found that African-American students in Newark are more likely to attend a school with good test scores than their counterparts in other parts of New Jersey.

Though evaluations of Booker’s reform effort were hampered when New Jersey switched from the NJASK test to the PARCC exam in 2014, the district reported major improvements in both math and English test scores on the PARCC exam over the past three years. Test scores are up 11 percentage points in English and 7 points in math, compared with 6 and 5 percentage points, respectively, statewide.

Another study, commissioned by the Community Foundation of New Jersey, found that 32.4 percent of Newark students in grades 3-8 passed the state math exam in 2017, up from 28 percent the previous year, bringing Newark closer to the state average of 44.2 percent.

Study author Jesse Margolis said Newark schools made significant strides in those grades, helping to reduce the achievement gap in the state and putting the city ahead of similar districts. In 2009, only 7 percent of black students in Newark attended a school that beat the state average on standardized tests. But in 2017, 27 percent of those students attended those above-average schools. Margolis argued that the $200 million from Zuckerberg and other donors that was spent over a five-year period — 4 percent of the total Newark school budget at that time — generated a big bang for the buck.

Analyzing data from 2009 to 2016 and accounting for the statewide improvements on the PARCC as all students in New Jersey became more proficient with the Common Core, Harvard Graduate School of Education economist Thomas Kane and a team of colleagues looked for the cause of these changes with funding from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Their research, published in the IRL Review this spring, showed that most of the gains in Newark were due to the policy of closing poor-performing schools and opening new ones, as well as streamlining the online system for applying to more effective charter and district schools. They ruled out other explanations for the jump in test scores, such as Newark’s early switch to the Common Core.

Margolis noted that Kane and his team would have found even more dramatic results if their research had included the 2017 data as well.

Persuaded by the conclusions of these studies, as well as by the evidence that the Newark-style reforms in Camden, New Jersey, were showing results, McGuinn said Booker’s school reform efforts were more successful than people realize.

Why haven’t these results gotten any traction? Booker responded that “nobody reads the academic studies.”

Regardless, he said he could look any kid in the city in the eye, ask where he or she goes to school, and feel confident that he did the right thing as mayor. “I just feel a sense of pride that we are fulfilling the promise of America here,” he said. “We’re not there yet. But we gave it our all and we are continuing to fight and now Newark is leading the pack.”

Choking up, he talked about his father passing away six days before he took office as a senator. Kids in Newark who grew up like his dad — “black, poor, to a single mother in a segregated environment” — are better off, he said, because of the changes he implemented in the city’s schools.

“It’s the proudest work that I’ve ever done.”

With education policy likely to play a significant role in the next presidential election, McGuinn said Booker could continue his support of charter schools and defend his record on Newark, despite the danger of being linked to DeVos’s school choice agenda, teachers union opposition, and the need to respond to the new left wing of the Democratic Party, by simultaneously calling for increased spending on education. He noted that Booker appeared on CNN in March to defend his support of charter schools.

“Let’s get out of this idea that charters are bad or good or traditional district schools are bad or good. I’m a big believer in great schools, and every kid should have public access to them,” Booker said. “I believe that any child born in any zip code in America should have a high-quality school, and I don’t care if that’s a charter school or a traditional district school. If it’s a bad school, I’m going to fight against it just like I supported charter school closures in Newark that weren’t serving the genius of my kids.”

“Booker is a remarkably effective communicator,” said McGuinn. “If anyone can make a compelling case for charter schools. it’s Booker. And if he pairs that message with large investments in traditional district schools, he can navigate a middle way in the Democratic Party on education reform.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)