Whitmire: Finding Brave New World of District/Charter Collaboration in Rebirth of Newark Elementary School

Newark, New Jersey

Against all odds, a dowdy elementary school with bright blue doors located in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in one of America’s most beleaguered cities has become a beacon of hope — and not just for Newark.

Think of the North Star Academy Alexander Street school as the little charter school that could.

What has played out here has lessons learned for both Newark and New Jersey, but also for the rest of the nation: Buckle up for the next generation of education breakthroughs, where public charter schools and local school districts team up to produce win-wins for both sides.

More evidence of the power of that linkage emerged this week with freshly released test results from a summer school experiment where the Uncommon Schools charter network, which runs Alexander Street, collaborated on a catch-up literacy program aimed at struggling rising second-graders in traditional Newark schools. For now, it suffices to say: There were dramatic improvements (more details to come).

And that’s just one of the spin-off effects of Alexander Street that can be traced back to the little school that could.

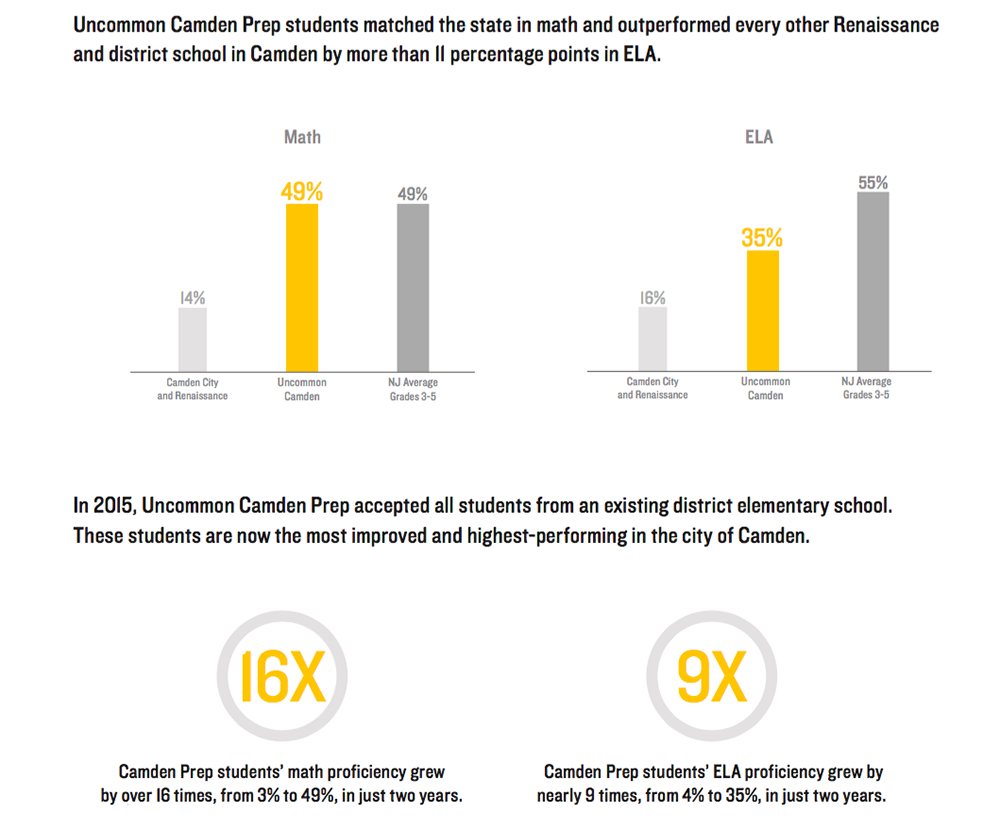

Another can be found in nearby Camden, where Uncommon Schools, emboldened by the success of the Alexander Street school, took on another transformation, which means taking over a failing school, including the students there from the previous year. The 2017 results at the renamed Camden Prep after just one year: dramatic upturns in both reading and math scores.

Telling the story of how Alexander Street became the little school that could requires delving into some history.

Bottling a school transformation

The narrative begins in 2011, when Cami Anderson, who was part of former New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein’s team that attempted radical school reforms there, got tapped to oversee the rescue of the long-failing Newark school system, which had already been taken over by the state. That was when Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg famously pledged $100 million to jump-start reforms there.

Knowing that charter schools lacked the capacity to transform Newark’s schools on their own, Anderson committed to reviving failing neighborhood schools, trying to give all students a shot at a better education, not just those who “won” charter school admissions lotteries. That proved to be difficult, especially at the Alexander Street school in the city’s West End, a neighborhood known mostly for its dangerous streets and drug trade.

Anderson recalls visiting the Alexander Street school and leaving in tears — nothing seemed to work.

Under relentless pressure from charters to turn over more unused Newark Public School buildings, Anderson, in January 2014, offered Uncommon Schools a building — with a challenging price tag. Her deal: You take over the Alexander Street school, keeping as many students as wanted to stay, and the building is yours.

Like most charter networks, which prefer to build their schools grade by grade, thus instilling the special school culture that makes them successful, Uncommon was wary of taking on a transformation, considered the trickiest of all school reforms.

But taking into account the lengthy waiting lists at its Newark campuses, Uncommon leaders concluded they had no choice and accepted the deal. For each grade, Uncommon brought in one experienced Uncommon teacher as a master teacher; the rest of the teachers were fresh hires.

Early on, the entire staff learned what it was up against. At a gathering in the school auditorium, the principal, Juliana Worrell, asked the third- and fourth-graders to count to 100 by 2’s. After the number 16, the only voices that could be heard were the staffers — the students couldn’t go any farther.

Determining the students’ skill levels was a severe challenge, as staffers had to keep switching to more remedial testing materials. Fourth-graders were unable to understand phonics and were reading at a first-grade level.

“Once we got these results, we had to throw out the playbook,” Worrell said. “We weren’t able to use our normal curriculum.”

They purchased phonics materials and focused just on phonics for 30 minutes a day. “By February, we were able to move into reading comprehension.”

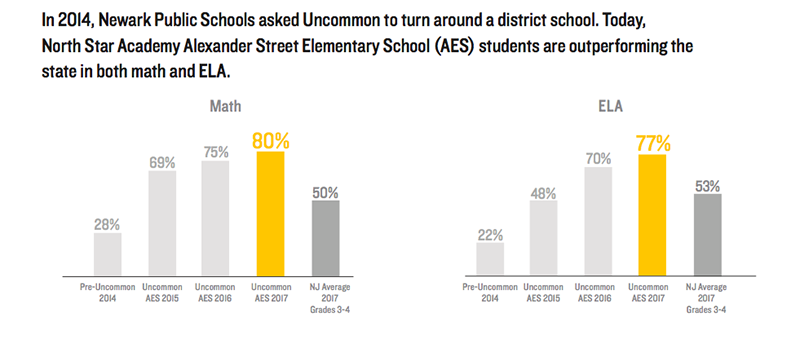

The Alexander Street staff was confident they were making progress, but even they were shocked at the first-year results on the new state PARCC test, which is aligned to the Common Core: In 2015, their students scored close to the state average for affluent districts in New Jersey and exceeded them in math.

It was no one-year fluke. The following year, the Alexander Street school outscored the affluent districts in both reading and math.

After The 74 wrote about the results at Alexander Street in January 2016, Chris Cerf, who succeeded Cami Anderson as Newark schools superintendent, came to visit. Was this for real?

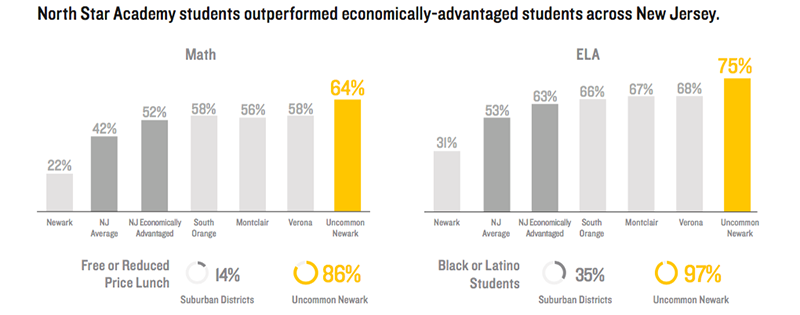

“North Star schools [as the Uncommon schools in Newark are known] were the clear outliers in the city, outpacing other charters as well as the traditional schools,” Cerf said. “I wanted to learn more about what they were doing.”

Cerf liked the reading instruction he saw, turning to a top aide who accompanied him and saying, “I want to bottle this.”

As soon as Cerf left the school, he started to look for ways he could import some of the Uncommon teaching strategies into his schools. Cerf, who served as a top deputy under Klein in New York City, dismisses the widespread fighting between charters and traditional schools as political distractions.

“We are indifferent as to how schools come into being, as long as they are free, high-quality public schools with equitable access to all kids,” he said.

Great Habits, Great Readers: great summer

Samantha Messer, who until recently oversaw reading programs for Newark district schools, accompanied Cerf on that visit to the Alexander Street school. She agreed with Cerf about the reading instruction: We need this.

What followed were several collaborative professional development meetings between the district and Uncommon staffs. Then Cerf asked Messer to set up a summer reading program to address a serious, and somewhat mysterious, district shortcoming: Kindergartners entered first grade mostly on track, but by the beginning of second grade they were falling far behind.

Why the first-grade losses? One can only speculate, but often school districts pull their best teachers out of first grade to put them in a “tested” grade, usually third grade, leaving the less capable teachers in first-grade classes. Regardless of the exact cause, something had to be done.

One part of what Messer (who now works at Uncommon) designed was taking the Uncommon reading program she and Cerf observed that day, Great Habits, Great Readers, and inserting it into a special catch-up summer school, where every child lagging in reading would get invited. What followed were training sessions, where Newark Public School teachers learned to use the teaching strategies.

“Uncommon has systematized reading in a manner that is easy for teachers to understand and use in their classrooms,” said Messer. “So we brought them in, and they ran their Great Habits, Great Readers program for a select group of teachers and literacy coaches.”

Next, the district organized an intense outreach program to draw the lower-performing rising second-graders into summer school. The outreach worked: This past summer, attendance rose to 750 students, a 50 percent increase.

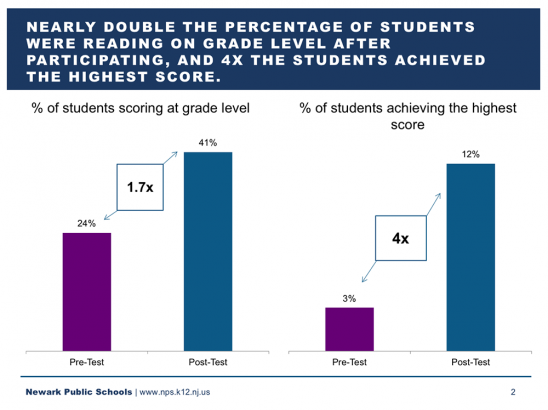

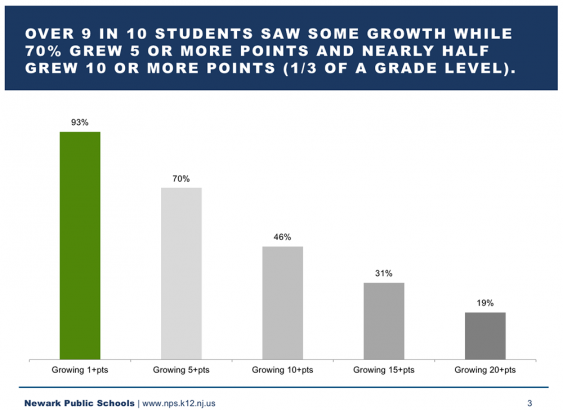

Just this week, the district released the results: Between the pre-test at the beginning of the session and the post-test at the end, the percentage of students scoring at grade level rose from 24 percent to 41 percent and the percent achieving the highest score rose from 3 percent to 12 percent. About half the students improved by the equivalent of a third of a year of regular classroom learning.

About half the students improved by the equivalent of a third of a year of regular classroom learning.

As Cerf is quick to point out, caution here is warranted. Only when those learning improvements are shown to stick through second grade and beyond will the experiment truly be considered a success. But clearly, the summer collaboration was a promising beginning.

Expecting the unexpected in Newark Public Schools

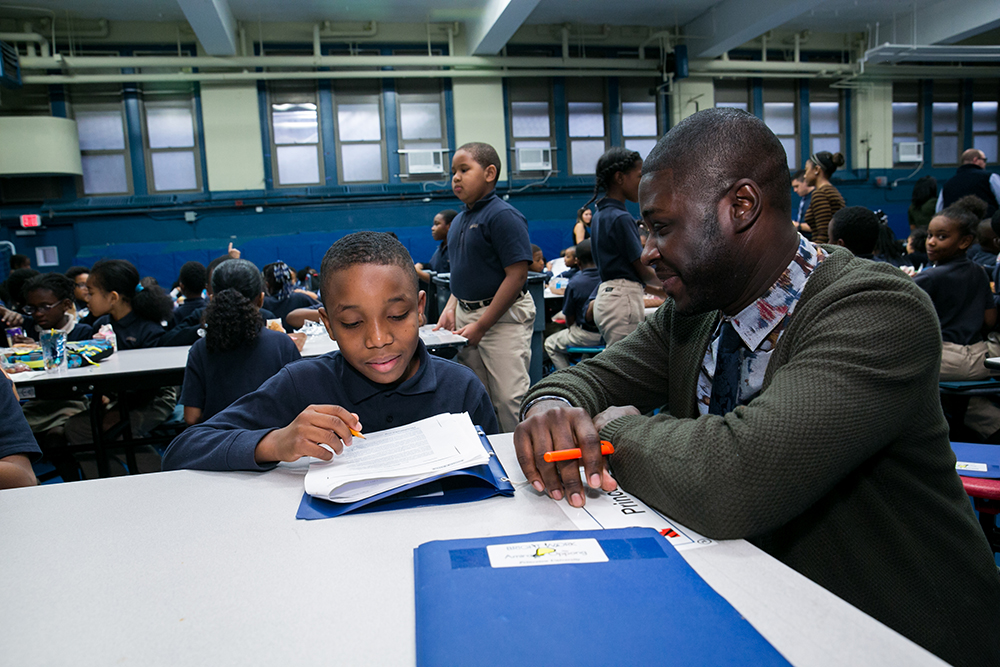

Second-grade teacher Lisa Battles at Newark’s First Avenue Elementary School sits in a small group reading session, her “low” reading group. To her right is Joseph, who participated in the summer reading session. Today’s lesson is dissecting the book The Cat Bandit, which tells the story of a wily cat trying to get at a freshly caught catfish.

Battles faces her struggling readers, trying to draw them out. In her hand, steering every move, is a Great Habits, Great Readers teacher’s guide, the literacy guide developed by Uncommon that Battles learned to use before the summer school program started.

At one point, the students get a special challenge: How to define the word drift without using the word drift. The context: the odor of the catfish “drifted” over to the cat.

For second-graders — for a lot of people, truthfully — this is a challenge. But today, Joseph seems up to the challenge. What got him engaged was Battles suggesting that he imagine his mother cooking pancakes, and the aroma filling the kitchen. He got it. The aroma drifted.

After the lesson, Battles sits down to discuss Joseph and her other students, and what she learned from the summer school program. If not for that session, students such as Joseph would never have raised their hands to tackle the definition of drifted, she said. It’s a matter of confidence, which is a matter of teasing meanings out of students. Sometimes, Battles said, the challenge for teachers is to say less than more. Let the students do the learning on their own.

Summing up her summer learning experiences, Battles said: “Challenge them a little more, don’t make it easy, and expect the unexpected.” A year ago, before getting the training, Battles never would have expected her students, especially the lower-level readers, to “get” the word drifted.

What’s the point of it all? To get her students to third grade prepared to do third-grade work. That’s pretty much what Cerf asked for.

On the way out the door, she asked someone from Uncommon Schools if she could have more copies of the teacher’s guide. Then the school literacy coach, who filled in for Battles while she discussed the summer program, asked for the same. It seemed infectious.

Figuring out the hippo is happy at Alexander Street

Starting this year, the new principal at Alexander Street is Newark native Na’Jee Carter. Although Carter grew up in a neighborhood not far from the school, he says, his mother and grandmother wouldn’t allow him to set foot in this neighborhood. Too dangerous.

Carter, who had been teaching at another Uncommon school in Newark, was recruited to come to Alexander Street by Worrell, the former principal, to be part of the first-year transformation in 2014. He accepted the challenge. Why?

“I was reflecting on the idea that the reason we do this work is because we believe it doesn’t really matter where a child is from, or whether the child is difficult. We believe that they can all achieve at high rates. So I wanted to take that chance to be on the right side of history.”

On the day I visited, Carter stopped by a kindergarten class to observe reading instruction. In one corner, teacher Akisha Robinson sits before most of the class leading them in a fast-paced, repetitive Reading Mastery lesson on sounding out letters. Mostly, the class sounds out in unison, but every few seconds Robinson calls out an individual student with: “Your turn.” Without missing a beat, the student sounds out the letter alone, and then Robinson shifts back to group response. The rhythm of the lesson has a musical quality.

Carter and I step outside the classroom to discuss what I’ve just seen.

“In Reading Mastery, there’s a lot of repetition, which really helps the students internalize what the letter is. Then they will go into the sounds the letters make. Eventually, they will move into words. You saw Miss Robinson asking a student ‘Your turn.’ That student is one of her struggling readers, so that allows the teacher to check for understanding. Does she know what letter that is?”

In the far corner of the classroom, teacher Danielle Buono leads a small group session on reading comprehension, using a baseball-themed Hurry Up, Hippo book. The specific reading skill Buono is focusing on: character feelings.

So what are the character feelings? “The students haven’t figured it out yet, but the hippo is excited, happy to be at the baseball game,” said Carter. “So the students are going to have to pull that out at some point when they read.”

The reading instruction I’m watching this day, right out of Great Habits, Great Readers, is the same reading instruction that got passed along in the summer collaboration with Newark Public Schools — the same instruction that led to impressive gains over the summer for most of the 750 students from the city’s traditional schools who attended.

And that’s the story behind Alexander Street becoming the little school that could — could turn itself around, could pass along lessons learned to Newark Public Schools, and could encourage Uncommon to take on another transformation school in Camden.

Welcome to the brave new world of charter/district collaborations.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)