The political pileup around efforts to improve schools in Newark, New Jersey, could have come from a Tom Wolfe novel: An aggressive conservative governor teams with a distressed city’s progressive but ambitious mayor in wooing a $100 million, five-year gift from a tech giant. The men sit in adjoining leather chairs as Oprah announces the breakthrough.

They hire a white New Yorker to run the school system in a city where 85 percent identify as black or Hispanic, that has a history of racial discord, and whose distrust of outsiders has sharpened in a fight to regain local control of its schools, which the state took over in 1995.

Administrators in Newark public schools, among the city’s largest employers, were habitually corrupt. Barely half of Newark public school students graduated. Nearly all were poor.

That was 2010.

Seven years later, Gov. Chris Christie is a lame duck, Cory Booker is a U.S. senator, and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg is more gigantic.

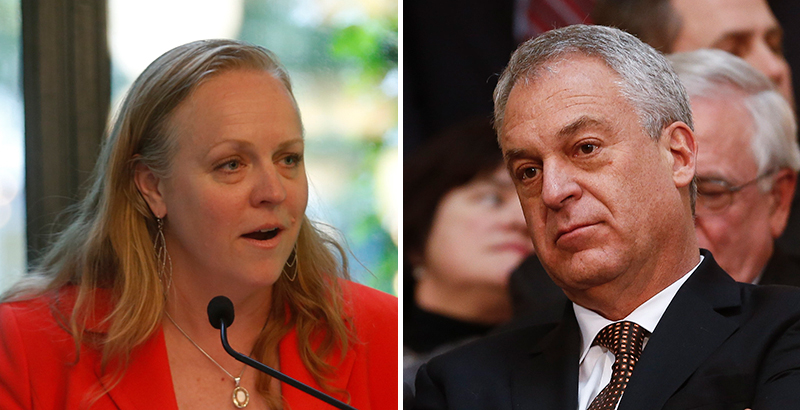

We also now have the first substantial study of results from the ambitious package of reforms implemented in the years that followed the announcement, carried out with unusual velocity by that new superintendent, Cami Anderson, and her successor Chris Cerf, who left his position as state superintendent to midwife Newark’s return to local control (which it won this September).

The “reboot,” as Anderson called it, included closing schools, opening new ones and expanding the city’s high-achieving charter sector, creating an enrollment system that allowed every child to rank preferred schools irrespective of location, and building new teacher compensation and evaluation systems.

(Although the Zuckerberg award created momentum for district-wide reform and helped fund a critical teachers contract, even when matched by another $100 million, it amounted to only 4 percent of the district’s budget during this period.)

A team of researchers led by Tom Kane, a Harvard economist who has produced influential research on teacher quality, studied fourth-to-eighth-grade student performance in the district as the reforms rolled out between 2011 and 2016. In a study released this week, Kane and his colleagues found:

- Students in both traditional and charter schools made larger gains in English in 2016 than in 2011; math gains were flat.

- Nearly two-thirds of the gains derived from more students moving to better schools — “enrollment shares following school effectiveness,” as Kane put it in an interview — largely because their low-performing schools closed or they enrolled in a charter. Twelve of 14 schools that closed ranked below the state’s average, driving students to more effective schools, while the charter population rose from 14 percent to 28 percent of the district.

- “Within-school” reforms, by contrast — efforts to improve existing schools by replacing principals, redesigning accountability, early focus on Common Core standards, and the use of blended learning, among others — contributed less than 40 percent to student gains.

- Gains weren’t consistent from year to year. Growth declined during the first three years of the study before improvements in 2015 (in both reading and math) and 2016 (in reading). Kane speculates that due to the magnitude of the changes “an awful lot of student movement in the earlier years” may have contributed to less growth, along with large numbers of teachers new to the district.

- The rise also coincided with the adoption of PARCC, an exam designed to test Common Core standards. While many cities suffered large drops in scoring on the new test, Newark students didn’t. District officials point to the use of a new Common Core–aligned curriculum; Kane did not find evidence, though, that the curriculum, or a large number of students opting out of the test, affected gains.

- The baseline for measuring Newark’s growth was the performance of students in similar New Jersey schools. The study doesn’t identify how any of the reforms led to improved gains.

- There are indications of improvement in Newark that are outside the study’s purview, including in graduation rates, which rose from 59 percent in 2010–11 to 73.5 percent in 2015–16.

Kane warns that the study “should not be cited simply as evidence for choice.”

“Newark saw what no other district in New Jersey saw. It was able to drive growth in market share in better schools,” he said. “One hundred million dollars only matters to philanthropists. The real question is, what do the results imply for what Newark does next?”

Disclosure: David Cantor worked with Cami Anderson and Chris Cerf while serving as press secretary at the New York City Department of Education from 2005 to 2010.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)