Study: Gaps in Civics Performance Between Black and White Students Deepened in NCLB Era

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Student performance in civics has improved over the past two decades, even as the gap in civic knowledge has grown along class and racial lines during that period.

That’s the conclusion of a new study released today by the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy. Its Report on American Education, an annual publication exploring trends in the nation’s schools, focuses this year on social studies and civics education. That choice reflects the degree to which schools have become a staging ground for political action — from activism around gun safety led by survivors of the Parkland massacre to the mass walkouts waged by teachers over low pay — authors explain in the paper’s introduction.

The turbulent 2016 presidential election, during which American voters were often deceived about candidates or current affairs by online purveyors of “fake news,” made the state of civics education a particularly fertile ground for inquiry, they argue.

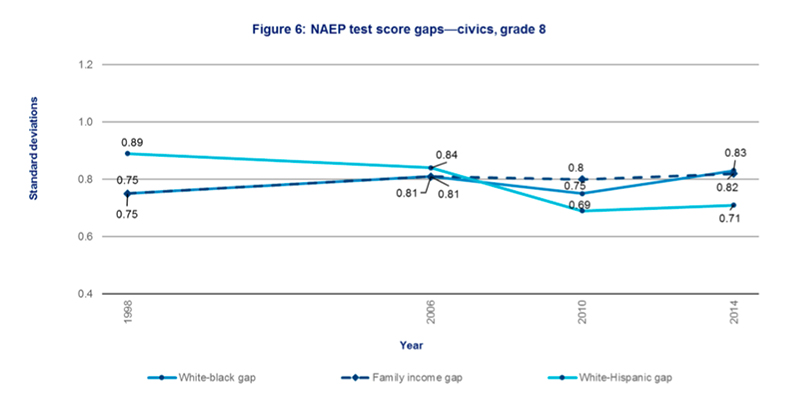

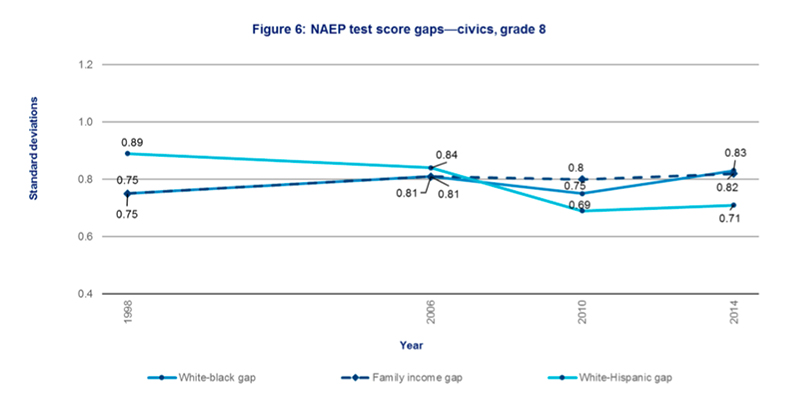

The study’s most striking findings relate to American students’ achievement on civics as measured on standardized tests like the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as “the nation’s report card.” The biennial release of NAEP scores for fourth- and eighth-graders allows education observers a window into the progress of classroom learning in the foundational subjects of math and science, but civics results have also been evaluated and released four times since 1998.

During that time, the study finds, pupils have seen slight upticks in their civic knowledge, roughly of the same magnitude as improvements in reading over the same time period. While NAEP scores in reading and especially math leaped upward during the late 1990s and early 2000s — the early years of what is generally considered the “accountability era,” when education reforms initiated by the Clinton and Bush administrations linked federal funding to performance on standardized tests — progress over the past decade has been essentially flat.

At the same time, curriculum experts have warned that NCLB’s particular emphasis on reading and math encouraged schools to devote extra class time to the teaching of those subjects, at the expense of disciplines like science, art, and civics. The study notes the evidence of this phenomenon, especially in low-performing schools enrolling higher percentages of disadvantaged students.

In an analysis of previously conducted school surveys, “we do see a reduction in instructional time devoted to social studies,” Elizabeth Levesque, a Brookings fellow and an author of the report, told The 74 in an interview. “There’s some evidence that suggests that crowding-out may have been happening as focus shifted to reading and math.”

Even worse were the comparative results. Since 1998, the disparities in NAEP civics scores between white or affluent students and their black or poor classmates have grown. This, despite a nationwide push to close achievement gaps, which has helped to bring minority students’ test performance somewhat closer to that of their more advantaged peers in other subjects.

The study goes on to examine the comprehensiveness of civics and social studies instruction by state, measuring the prevalence of high school civics requirements, extracurricular activities, media literacy, and opportunities for service learning. Civics experts increasingly make the case that study of government, history, and democratic processes is inadequate to ensure that students are being prepared for the demands of citizenship, and that teaching must be paired with participatory elements such as community service.

“The really important question to focus on is not just classroom instruction,” Levesque said. “Looking at coursework as a foundation is really important. But one of the things we’re trying to do is expand the conversation a little bit broader so that we’re also talking about more action-based civic engagement … for students to develop not just their knowledge, but also their skills and the dispositions they need to effectively participate” in civic affairs.

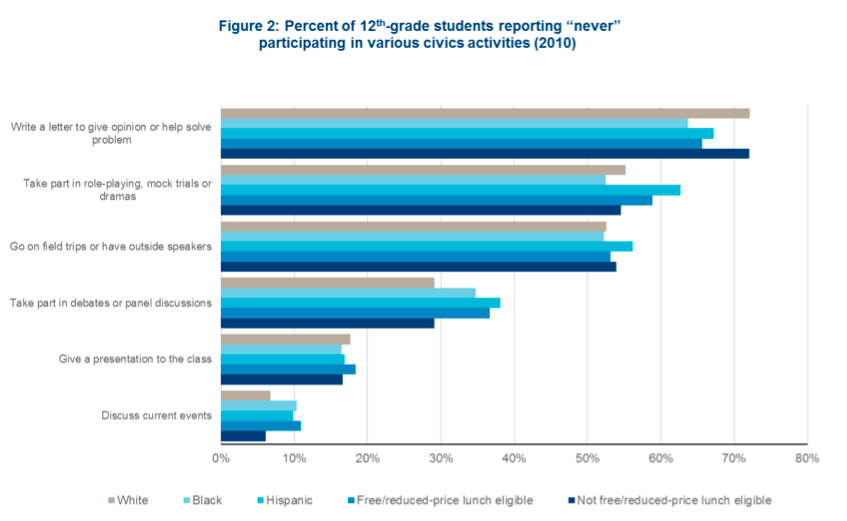

Analysis of student surveys shows that a disturbing number of students, among all racial and income groups, report “never” participating in civics activities like writing a letter to a local newspaper, participating in classroom activities like mock trials, or going on field trips.

Even where the study finds that states have implemented robust civics instruction — by including the completion of a social studies or government class as a high school graduation requirement, for example, or devoting some portion of class time to the discussion of current events — there is cause for concern. Although 40 states require high schoolers to take at least one course related to civics, a February report from the Center for American Progress found that only nine (along with Washington, D.C.) mandate a full year of coursework. That report also observed that the national average score on the Advanced Placement U.S. government exam is the fourth-lowest among 45 AP subject tests.

The replacement of No Child Left Behind with the Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015, allows states greater freedom to adopt new educational practices and focus on academic areas separate from reading and math. The study’s authors write that school authorities in every state may find latitude in the new law’s provisions to emphasize social-emotional learning and school climate — two measures they consider supportive of civic engagement.

“A common refrain right now is, ‘With this flexibility under ESSA, maybe now is a time for states to do X, Y, and Z,’ and I don’t necessarily want to get on that bandwagon,” said Levesque. “At the same time, [the transition period] could be a turning point if it leads to a large shift in accountability frameworks. It seems possible that these new approaches could get traction.”

Perhaps the report’s most surprising finding comes in its final chapter, which examines the state of the social studies workforce. At the time of their hiring, social studies teachers are more prepared (in terms of previous courses taught) and better compensated (their average salary is higher than that of English or science teachers, though slightly lower than math teachers) than most of their colleagues. They are also strikingly more likely to be male.

While just 20 percent of English teachers are male, along with 38 percent of math teachers and 41 percent of science teachers, a whopping 57 percent of social studies teachers are. Thirty-five percent also report working simultaneously as coaches of sports at their schools, a much larger proportion than teachers of other subjects.

Go Deeper: This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. See our full series.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)