Amid U.S. Anti-Vaccine Movements, Puerto Rico Vaccinates 89% of Eligible Youth and 98% of School Staff

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In July, news of a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for all eligible public and private school students broke quietly in Puerto Rico. Without massive protests or threats of violence — and even before it was required — the bulk of the island’s youth aged 12-17 got vaccinated in May and June.

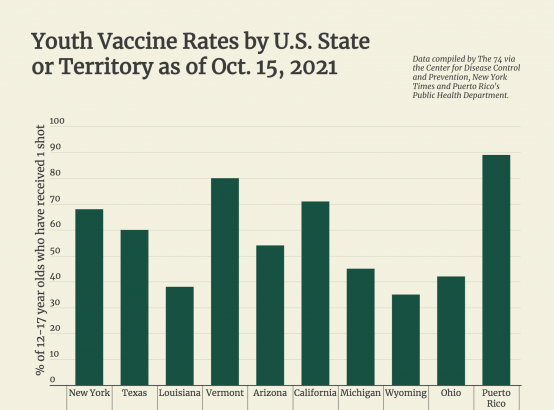

In order to return to school in person post-summer break, all eligible students were required to show proof of receiving at least one dose. Today, 89 percent of the young population are at least partially vaccinated, a rate higher than any other mainland U.S. state or territory.

The CDC also reports 98 percent of Puerto Rico’s school workforce of roughly 60,000 was vaccinated by the end of March, within six weeks of opening eligibility to the group. To prepare for school reopenings, teachers were included in the second eligible wave, accessing shots just after health and residential care workers.

The CDC also reports 98 percent of Puerto Rico’s school workforce of roughly 60,000 was vaccinated by the end of March, within six weeks of opening eligibility to the group. To prepare for school reopenings, teachers were included in the second eligible wave, accessing shots just after health and residential care workers.

The island of about 3 million has boasted higher-than-average vaccination rates since rollout, having finalized its robust mass vaccination plan in October 2020, well before distribution. Their work provides an opportunity for a case study of successful adolescent vaccination, as most U.S. states struggle to get shots into their school-age population.

That mass vaccination efforts in Puerto Rico are outperforming mainland U.S. states may come as a surprise to those accustomed to stateside news outlets which frequently depict the island as being in constant disaster recovery. While Puerto Rico has faced serious hardship, it appears to have pulled together in the face of COVID-19 in a way that has eluded other Americans.

When folks think about highly vaccinated places in America

They think Vermont or CT or MA

Those places are good

But not the most vaccinated place in America

So who’s #1?

Puerto Rico!

But PR has gotten way too little attention

Its worth reflecting on how they did it

Thread

— Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH (@ashishkjha) October 17, 2021

“In Puerto Rico, the pandemic was never politicized … People were really rowing in the same direction.” Daniel Colón-Ramos told NBC News back in March. Colón-Ramos is a professor of cellular neuroscience at Yale University and president of Puerto Rico’s Scientific Coalition, a group of experts advising Gov. Pedro Pierluisi on the island’s Covid-19 response.

As of Sept. 29, 56 percent of U.S. youth aged 12-17 had taken at least one dose of the vaccine, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, while 68 percent of adults have completed their sequence. Yet the rates drastically vary by region; in 21 states, less than half of youth are vaccinated. About a third of adolescents hospitalized with the virus required intensive care, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scholars, residents and local leaders chalk Puerto Rico’s comparative success up to far-reaching mandates across industries, lower political polarization, older generations’ trust in a once-public health care system and a common belief in getting students back in classrooms — by any means necessary.

“They urgently needed to get students back to school in person because they couldn’t take it any more. They were hurting and needed to be there, with their teachers,” said Edgar Bonilla, a single father of three living in Caugus, a mountainous city about 20 miles south of San Juan.

Bonilla, one of several island residents interviewed by The 74 in Spanish, said he witnessed at least five of his children’s peers leave school last year out of frustration and feeling lost with online learning. Those that stayed may have progressed to the next school grade, he says, but need support with understanding material.

And while there have been a few dismayed teachers since the mandate, he believes “you have to see the other side” — students without needed resources, those who can’t effectively learn online with audio or speech disabilities or who live with chronic health conditions.

“The student who’s unvaccinated, for religious or health reasons, has to take COVID-19 tests the whole week to enter school. Really all have to be vaccinated. There are students with chronic asthma, diabetes, or who are cancer patients like myself,” Bonilla said. The stress of everyone’s health during the pandemic, “has affected me a lot mentally.”

His 14- and 15-year-olds excitedly got both doses before this school year. Their household continues to wear masks outside their home and washes their hands regularly, to protect their unvaccinated 11-year-old sister.

And at the Bonillas’ public high school, youth stay in the same classroom all day. Only teachers rotate between rooms, to make any student quarantines smaller and easier to roll out. Lunch is outside, in small groups with open air, or in smaller capacity classrooms for younger children.

Puerto Rico Department of Health’s July 22 administrative order extended the vaccine requirement to all school staff and anyone entering school buildings. Families told The 74 enforcement is strict to minimize contacts — if you forget your vaccination card, for instance, school staff or your child must come find you outside or meet at your car. No exceptions.

The only comparable sweeping K-12 mandate in the mainland is for California’s K-12 children. Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the requirement for all eligible students on Oct. 1, yet it’s unlikely to go into effect until July 2022.

Some California districts are weighing vaccination mandates because of concerningly low vaccination rates among youth. And where they have been adopted stateside, many are not complying and at least two — in Los Angeles and San Diego — are being challenged in court.

Three weeks ahead of its deadline, Los Angeles Unified estimated 80,000 students had not yet gotten a dose. The district recently extended its deadline for educators to Nov. 15, fearing the original cutoff would worsen critical shortages, though roughly 95 percent of educators have met the requirement. And New York City’s mandate for educators faced protests, legal and union challenges, but now about 96 percent of their teaching force has gotten one dose.

Overall, there are more states that ban vaccine mandates for school staff (14) than have instituted them (11). In further contrast, when Puerto Rico did announce its mandates, no formal opposition followed.

In late March and April, the island saw an uptick in cases. And though no outbreaks were linked to the roughly 100 schools then open part-time for special education and young children, all closed for two weeks in an abundance of caution. The closures seemed typical of the system’s strict approach to COVID-19 safety.

Following a July vaccine order for all government employees, Gov. Pierluisi also mandated this August that many private businesses, including restaurants, salons, casinos and gyms, require all employees to show proof of vaccination. Those claiming an exemption must show negative test results weekly. Businesses must also require that their customers show proof of vaccination or cut capacity by 50 percent.

The constant guidance from health and government officials has helped families return to in-person learning, though some schools are now facing closures amid a wave of random blackouts unrelated to the pandemic. In addition to dealing with infrastructure damage from years of destructive hurricanes, Puerto Rico’s circa 1976 power generation units are twice as old as those stateside and due for major replacements.

For many, vaccination is the one factor they can control to keep children in school.

Daniel Pacheco says there’s a “responsibility” felt among families when it comes to the mandates. His family of four lives in Aguadilla, a city of about 55,000 on the island’s northwest tip where about 73 percent of the population has been vaccinated, and has seen the pandemic’s impact firsthand. His wife, Marizabel, is a nurse.

“My wife and I think the same way, that teachers in direct contact with children have to be vaccinated to avoid the spread,” he said. “I think [the vaccine] should be approved and given to all kids because there’s already scientific evidence that it’s really beneficial for them to get vaccinated.”

Their school hosted a virtual open house before classes resumed to explain how exactly quarantine protocols would work. His two children, ages 6 and 10, returned to school for the first time fully in person this August and will be vaccinated once eligibility is extended to their age group. The Federal Drug Administration will review Pfizer’s request to extend vaccine eligibility for youth 5-11 on Oct. 26, and authorization may follow in early to mid- November.

While parents in Puerto Rico say there hasn’t been much widespread hesitation, a recent parent poll across the U.S. revealed roughly 51 percent would vaccinate their children when eligible. Low adolescent vaccination rates raise concern for recently opened mainland schools now facing threats of closure with student and staff quarantines. As of Oct. 10, COVID-19 outbreaks in the 2021-22 school year precipitated about 2,265 school closures in 580 districts according to Burbio, a website tracking school policies and schedules.

For instance, amid rising Delta variant cases, recent efforts in Newark, New Jersey were able to double the city’s youth vaccination rate to 55 percent, a rate still leagues behind Puerto Rico’s. The key, local leaders say, was making the shot available at schools, churches and essential community organizations; stopping misinformation and deploying health officials throughout the community to address concerns.

One Puerto Rican nonprofit leader whose organization distributed vaccines told the Miami Herald that he believes using community groups to administer vaccines has made the difference for small populations skeptical of the government or pharmaceutical industry.

The strategy of spreading secure information at the local level could help Puerto Rico reach herd immunity, local journalist and mother Paola Arroyo said.

Similar to the anti-vaccination camps on the mainland, some of those holding out, “are not very aware of how beneficial the vaccine is and are carried away by fake news on social networks or platforms that aren’t necessarily official,” she said. Others aren’t vaccinated for religious or health reasons, or lead a kind of natural lifestyle and prefer to build immunity without vaccination.

A 29 year-old resident of Guaynabo, just outside of San Juan on the northern coast, Arroyo stays cautiously hopeful. She regularly sees youth, even infants, wearing masks outside and taking stock of health guidelines posted outside businesses.

“Youth are very aware of the problem that we’re confronting. They’re more aware than adults themselves,” she said.

Arroyo had her first child during the pandemic, and though vaccines weren’t available during her pregnancy, she was “confident” when getting both doses as soon as she became eligible. With encouragement from her pediatrician, she is passing antibodies onto her 9-month-old daughter Valentina through breastfeeding.

“I’m going to get the booster when it’s available and continue breastfeeding to protect her,” Arroyo said. “I believe in the power that vaccines have and understand that it’s a social responsibility.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)