By the Numbers — How 100 School Systems Are (and Aren’t) Adapting to COVID: When to Mark Quarantined Students Absent, and What Constitutes an Outbreak

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This the latest in a series of weekly analyses of COVID-19 policies in 100 large and high-profile school systems, produced by the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, Bothell. You can see the full archive here.

For better or worse, the flurry of new public health measures that marked the start of the 2021-22 school year has quieted.

States have largely stopped enacting vaccine mandates for teachers. Battles over masks have mostly shifted from the statehouse to the courthouse, with judges in Iowa, Oklahoma and South Carolina recently siding with school districts that defied state bans on mandates.

The critical task facing state policymakers now is adapting to a school year in which schools will need to minimize disruptions caused by quarantines. This may be more complex for school systems to manage than last year’s school closures, since the disruptions are occuring at the school or even classroom level.

At a time when students are shifting in and out of isolation, and between in-person and virtual learning, states must help schools rethink how they track attendance and enrollment. Otherwise, they may struggle to accurately understand where students are, whether they are learning and how budgets might shift in the future.

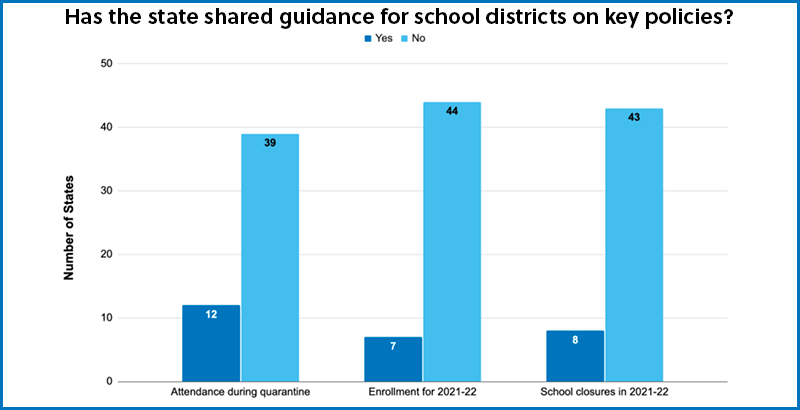

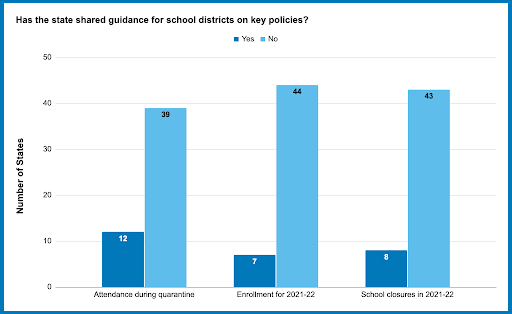

But far too few states have equipped school systems to adapt to this year’s new reality. Specifically, most states have not clarified how districts should track attendance for students who have to quarantine. And they have been slowto help districts minimize quarantine-related disruptions while keeping students safe.

Attendance, Enrollment and School Closures

The pandemic obliterated some simple assumptions about how school was supposed to work. Before, students who showed up for class were marked present. Those who did not were marked absent.

But how should attendance policies apply when more students than ever before are learning at home due to quarantine? Is it fair to penalize students who have been asked to stay home because they were exposed to the virus and might be contagious? Many states are leaving school districts on their own to figure out answers to these questions.

Only 12 states have provided guidance on how to take attendance when students are in quarantine. Four of them direct districts to mark students absent. The other eight set standards for marking students present.

Texas tells schools to mark quarantining students present if they’ve engaged in four hours of instruction, including at least two hours of live teaching. Oregon released a framework that standardizes attendance rules for both in-person and virtual classes. It requires students to participate in classroom activities and have “substantive interaction” with a licensed teacher during the school day.

Nebraska released an attendance policy that will expire in July. It directs districts to support student learning during quarantine, and not to count students absent if they participate in school-sponsored instruction.

In California, defining absenteeism could have major consequences for school budgets, since state funding is tied to students’ average daily attendance.

Just eight states have provided explicit guidance on when schools should consider closing during the 2021-22 school year. Some states, like Illinois, offer vague guidance for districts to collaborate with local health authorities. Pennsylvania, by contrast, sets specific definitions for what constitutes an outbreak and guidelines on how long schools should close.

Some states and districts are responding to a groundswell of frustration with the disruptions caused by quarantines by working to minimize them as much as possible. For example, Florida recently ordered that quarantines would be optional for students exposed to the virus. But it did not combine this step with measures designed to keep students safe while in school.

Our analysis of 100 large and urban districts finds school systems are increasingly using COVID-19 testing to ease quarantine requirements, but like Florida, most states are not providing them with guidance on how best to do this. Twelve states — most recently, Vermont — give districts guidance on “test-to-stay” programs that let students avoid quarantine if they take regular COVID tests that consistently come back negative.

Kansas is working with local health departments to implement a continuum of plans for school-based testing programs. For example, the “test-to-know” plan helps districts create testing programs for all students to detect outbreaks before they spread in schools. The “test-to-stay and learn” is designed to let students who were exposed to the virus safely avoid quarantine. And the “test-to-stay, play and participate” plan outlines testing protocols for students who were exposed to the virus and still want to participate safely in sports or extracurricular activities.

If more states provide this level of detailed guidance and support to districts, it will help school systems keep students safe and learning. But they will still need to overcome other barriers keeping schools from implementing COVID testing — including problems with the supply and distribution of tests.

Increasing demand for COVID-19 tests due to the delta variant has complicated the task of getting them to schools. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra explained during a congressional hearing that the federal government is working with states to understand where tests need to go—and to get them to places where the need is greatest.

Stalled progress on vaccine requirements

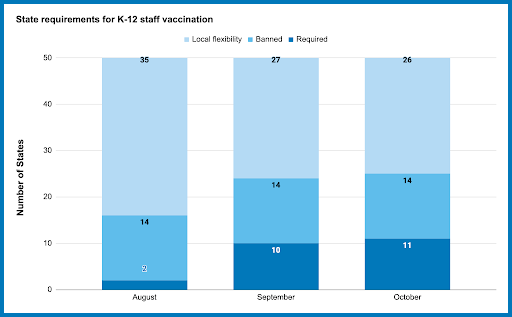

Only one state — Delaware — has imposed a new vaccine requirement since early September. Its mandate will take effect Nov. 1.

Of the 11 states requiring staff vaccinations, eight let teachers opt out through regular COVID-19 testing. The number of states requiring inoculation for school staff remains lower than the number — 14 — that ban vaccine requirements.

Most of the remaining states leave the decision on imposing mandates up to school systems, and some incentivize vaccinations. In Massachusetts, once a district reaches 80 percent or more vaccinated students and teachers, it does not have to enforce a mask requirement.

Most of the remaining states leave the decision on imposing mandates up to school systems, and some incentivize vaccinations. In Massachusetts, once a district reaches 80 percent or more vaccinated students and teachers, it does not have to enforce a mask requirement.

In the absence of vaccine mandates, states can still increase transparency so parents and teachers can know how many people in their schools are vaccinated. But another analysis from the Center on Reinventing Public Education of reopening guidance in 50 states plus the District of Columbia finds only a single state — Maine — is reporting clear and accessible data on COVID vaccinations in schools in a publicly accessible format. This month, the state released two new dashboards on teacher vaccination rates by school and student vaccination rates by district.

Solving short-term pandemic problems can lay the groundwork for long-term improvements

The challenges districts face with attendance this year aren’t going away. More students are enrolling in online schools. More school systems hope to use online learning to eliminate sick days or snow days.

Designing policies for measuring student attendance, participation and enrollment in a year of quarantines will help school systems in the future. Districts can’t be left to solve these problems on their own. They need state leadership.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)