The State of America’s Foster Care Students: How the Every Student Succeeds Act Is Designed to Better Understand and Support These 430,000 Kids

Updated July 25

One of Jordon Marshelle Barrett’s biggest obstacles to graduating from high school had nothing to do with her classes. As a student in foster care, Barrett found herself shuffled between homes and across school zones, sometimes stranded without transportation to class.

The 18-year-old missed months of school and had to repeat senior year.

“It’s a really big setback,” Barrett said. “I understand why a low percentage of foster care students are graduating from high school, because it’s hard if you’re not dedicated to keep trying.”

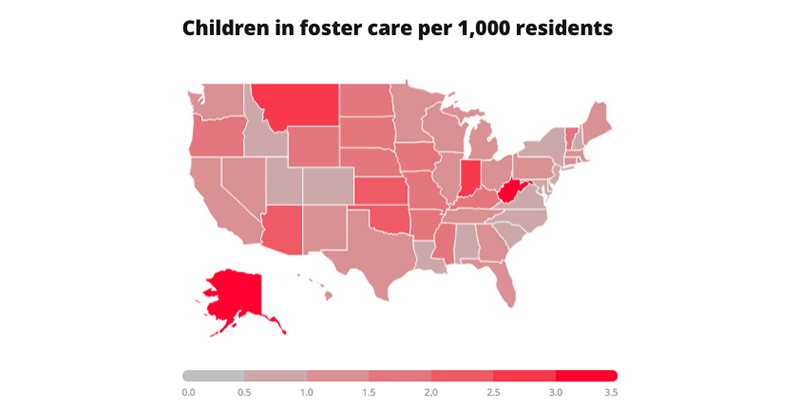

Transportation is just one of many challenges the more than 430,000 U.S. children in foster care face as they struggle to get an education. About one-third of foster care students change schools at least five times before they reach adulthood, and for each school change, they tend to fall four to six months behind. Meanwhile, they are coping with the trauma of being separated from their families.

By the time these students are adults, they reach only an average seventh-grade reading level and have been three times as likely as their peers to get expelled, according to data collected by the Legal Center for Foster Care and Education. Only 11 percent obtain a bachelor’s degree.

But while many experts agree that this student population is the one that needs the most help, assistance rarely comes. One reason is that their numbers are small: 260,000 school-age kids, just 0.5 percent of students nationwide. Another is that most state education departments don’t communicate with child welfare agencies about which students are in foster care. As a result, there are little or even no data on these children’s academic achievement, graduation rates, mobility, college success — even who the foster care students are.

ESSA prioritizes foster care student performance

Recent changes in federal law are aimed at addressing this. The Every Student Succeeds Act requires state departments of education to collaborate with child welfare agencies so education leaders can begin tracking which students are in the foster care system and how they’re doing academically. ESSA also mandates that states arrange transportation for foster care students to their original school if they move between homes, to minimize disruption to their education.

This winter, for the first time, states will also be expected to include data on the educational outcomes of foster care students on their state report cards, as they already do for student subgroups like English learners and migrants.

“This is a big step forward in terms of giving students in foster care the attention they need,” said Kristin Kelly, senior attorney and assistant director of education projects at the American Bar Association.

Whether states can abide by the new law is another matter. Experts say getting state agencies to share sensitive data is a challenge. Additionally, smaller, rural areas may only have one or two students in foster care, making it impossible to publicly report on them because of privacy concerns.

“Everyone understands these children need a lot of help, a lot of support, but it’s a lot of work for maybe no data in the end if your population is really small,” said Elizabeth Dabney, director of research and policy analysis at the Data Quality Campaign. “This is the real heartbreaker of this — these are the kids who need it the most, but they’re such a little group.”

A state-by-state data fight

While most states don’t track educational outcomes of students in foster care, advocates pointed to several that do, including California, Texas, Washington state, Colorado, and Washington, D.C.

In Washington state, where the five-year graduation rate for foster care students is 49 percent (compared with 82 percent for all students statewide), the battle to share data took about 15 years, said Janis Avery, CEO of Treehouse, a Seattle-based nonprofit, who helped lead the effort to align and publish statistics on foster students’ achievement.

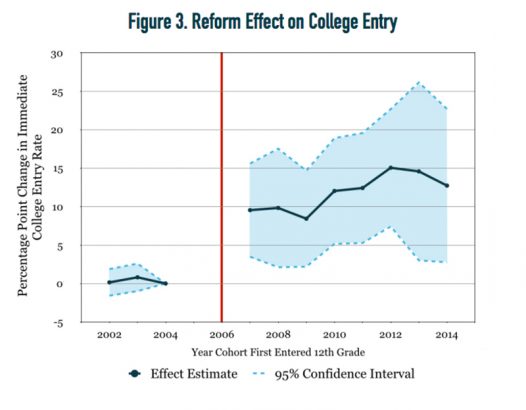

Treehouse supports foster students in high school by pairing them with adult mentors who help keep them on track and support their post-graduation goals. Students who participate in the program, called Graduation Success, have a five-year graduation rate of 89 percent, Treehouse reported.

Barrett has worked with Treehouse education specialist Merissa Humes and calls her “like a second mom.” Humes has helped Barrett with everything from completing her FAFSA to meeting with college admissions officers to helping her when her car was totaled in a crash.

The program currently serves 2,500 students in the greater Seattle area and hopes to expand to assist all foster care high schoolers in the state by 2022.

In Colorado, collecting and reporting data produces a “moral obligation to act,” said Elysia Clemens, deputy director of the Colorado Evaluation and Action Lab, part of the Barton Institute at the University of Denver. The state’s four-year high school graduation rate for students in foster care in 2017 was 24 percent.

“Having the concrete information that students in our care in Colorado — only 1 in 4 graduated with their class last year — creates a sense of responsibility for people to act,” Clemens said.

This year, Colorado also became the first state to pass a law funding transportation to a foster student’s original school.

ESSA required states by the end of 2016 to have plans in place for transporting students from their homes to their “schools of origin,” but an analysis from the Chronicle of Social Change found that 11 states are having trouble complying, affecting some 162,000 kids.

Some call ESSA’s new rules for students in foster care unfunded mandates, while others worry that foster students’ difficulties will be underreported because many states will have trouble collecting and sharing data. Not only are there technical challenges in aligning different databases, but the agencies must agree on how best to handle confidential information about children.

Based on Colorado’s experience, Clemens recommends that states use a neutral organization to help support the data-sharing work. She said it’s difficult, but she hopes it’s doable.

“We have a unique responsibility for students in foster care because a judge has said their parents can’t take care of them and has made them state-dependent, so they are all our children,” Avery said. “That’s why the federal government is moving the way it’s moving.”

For more data and research about the state of America’s schools, see The 74’s ‘Big Picture’ number series. Other recent findings of note:

College Ready?: In 46 states, high school graduation requirements aren’t enough to qualify for nearby public universities

Education Funding: The states that spend the most and least on education — and how their students perform compared to their neighbors

Charter Schools: Traditional public schools see higher test scores when a charter school opens nearby

Teacher Diversity: Why the race to find bilingual teachers? Because in some states, 1 in 5 students are English Language Learners

Self Esteem: National survey shows one-third of girls with 4.0 GPAs don’t believe they’re smart

New Orleans: After Katrina-inspired school reforms, report shows New Orleans students now more likely to attend — and graduate from — college

Go Deeper: See our complete ‘Big Picture’ archive

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)