Why the Race to Find Bilingual Teachers? Because in Some States, 1 in 5 Students Is an English Language Learner

There is a persistent shortage of dual-language teachers as the number of English language learners in American schools continues to rise. While a number of districts have looked to the short-term solution of hiring from Spanish-speaking countries like Spain and Mexico, two new papers from New America highlight recommendations for how to incubate bilingual talent stateside.

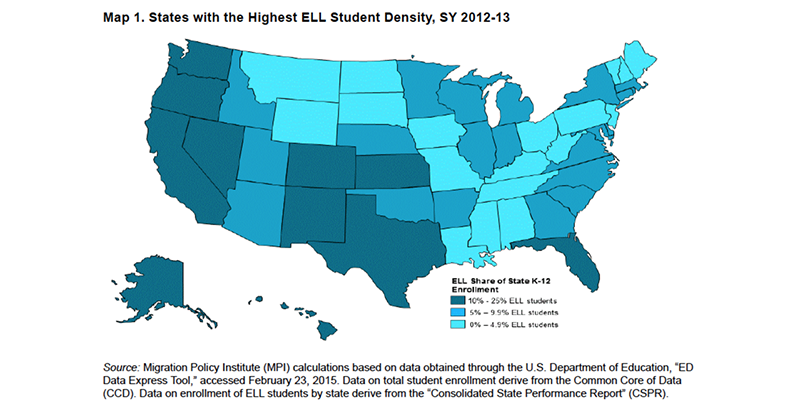

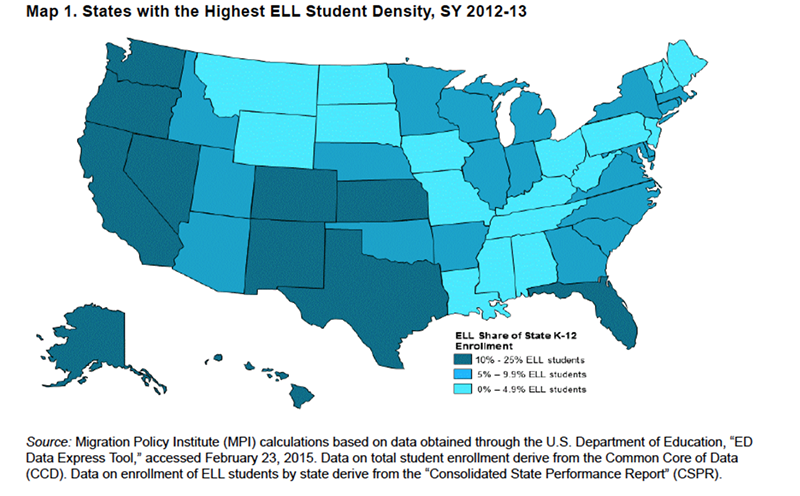

Roughly 5 million K-12 students in the United States are classified as ELLs, specifically targeted for assistance in achieving English proficiency. That accounts for about 1 in every 10 American schoolchildren, the great majority of them children of Spanish-speaking immigrants. And although they are sometimes assumed to be clustered in states like California, Texas, and Florida, tens of thousands have also trekked to the Pacific Northwest.

The two new papers from New America showcase the region’s struggle to recruit qualified bilingual educators and help ELLs catch up with their native English-speaking classmates. Researchers identified methods that have helped remove licensure barriers and bring more dual-language educators into the system, though they also highlight the danger posed by President Trump’s threat to rescind Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

According to a 2015 study by the Migration Policy Institute, the state of Washington boasts the eighth-largest ELL population in the country, and both Washington and Oregon are among the nine states with the highest ELL student density. Stymied by a dearth of existing candidates with highly specialized credentials, two districts in those states resolved to create their own. Yet both will struggle to retain them if the Trump administration makes good on its commitment to end DACA, which is estimated to protect 20,000 teachers from deportation.

Although reports abound of DACA-eligible students wracked with uncertainty over their immigration status, the full impact of the program’s repeal will be borne by countless other children if their teachers simply disappear from school. Denver Public Schools Superintendent Tom Boasberg, who presides over a district that is over 30 percent ELL, said in a recent Vox interview that he has specifically tried to attract DACA teachers.

“It’s hard to find great teachers, period. Great bilingual teachers is even more important,” he said. “And we have very strong teachers here that we’ve invested in and helped train.”

Mexico’s education department has announced that it will gladly hire returning Dreamers to act as English language instructors if the program is not renewed by act of Congress. In what could be the greatest irony of the DACA saga, Americans may soon find that they had access to a small army of potential bilingual teachers — but instead of deploying them to fill a dire shortage at home, they paid to send them to a foreign country.

In the first report, New America researcher Amaya Garcia studies an alternative certification program in Western Washington’s Highline Public Schools. Of the district’s nearly 20,000 students, about 25 percent are ELLs, and a local absence of bilingual teachers has forced administrators to come up with a creative solution: the Woodring Highline Future Bilingual Teacher Fellow Program. Participants in the two-year fellowship can earn bachelor’s degrees and K-8 teaching certificates by working as full-time classroom paraprofessionals and taking education classes on nights and weekends.

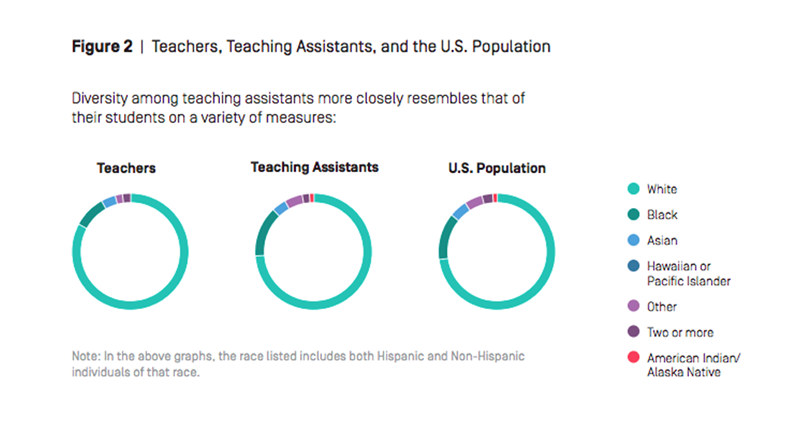

Targeting paraprofessionals for roles in bilingual instruction is demographically savvy, Garcia writes. While teachers are much less likely than the greater public to be Hispanic, bilingual, or foreign-born, classroom aides essentially mirror national averages in all three categories.

The Future Bilingual Teacher Fellow Program, funded in part by state grants, represents just one facet of Washington’s mission to buoy English learners. Gov. Jay Inslee and the legislature have worked for years to channel more funding to dual language immersion programs, and the state monitors the academic outcomes of all students who were ever designated as ELL.

(The 74: 3 Ways Washington State Leads the Nation for English Language Learners)

In neighboring Oregon, Portland Public Schools — the state’s largest school district — had already offered dual language immersion for 25 years when the city moved to dramatically expand its offerings in 2011. The move proved popular, and soon more affluent, English-speaking parents were seeking bilingual education for their own children. So overwhelming was the demand for placement that an enrollment lottery turned away nearly as many students as it accepted. Suddenly, the district needed at least a dozen more bilingual teachers.

“We have a staffing shortage,” a district employee told Garcia. “We’ve done trips to Puerto Rico, we have brought in visiting international teachers, but that’s still not meeting the need that we have. So we decided that we need to grow them ourselves.”

In 2016, the district teamed with Portland State University to create its own talent pipeline, the PPS & PSU Dual Language Teacher Partnership. The university, which has already run its own bilingual teaching pathway for decades, helps screen applicants for the 28 fellowship slots. Recruits must hold a bachelor’s degree, pass a language fluency test, and gain admission to one of the school’s education programs. Once accepted, they are employed as either lead teachers, substitutes, or paraprofessionals while working on their graduate coursework.

A year into the program, the district has placed teachers in all of its bilingual education positions. According to the district’s director of dual language programs, “It’s been very, very successful. We don’t have a bilingual teacher gap at this point.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)