Pandemic Yearbook: 9 Students — in Their Own Words — on Life, Learning and Loss as the Coronavirus Pushed into a Second Turbulent Year

By Andrew Brownstein | July 6, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

It was only Feb. 27, 2020 — a mere 17 months ago — that the first school in the United States closed due to COVID-19.

Somehow it seems longer in pandemic time.

For students, like everyone else, that temporal elasticity could be chalked up to a host of things, from the monotony of quarantine to isolation from family and friends to the mostly invisible barriers between the spaces where we worked, played and dreamed.

In March 2020, The 74 launched “Pandemic Notebook,” an intimate series designed to capture, in their own words, how students are living through this strange period.

Few understood how long it would last. Initially, it just seemed like Spring Break was taking longer than usual. But then the goalposts for a return to normalcy kept shifting: the end of the school year, the fall, the conclusion of Biden’s “First 100 Days.”

It still hasn’t happened.

For students in a once-unthinkable year two of pandemic school, the stories deepened as quarantine wore on. Some grappled with young love in a time of virtual connection; others, locked inside their homes, experienced the deep trauma of parental abuse. They faced issues that are perennial: privilege, college and equity, making new friends. They also tried new things. A fifth-grader in Michigan took advantage of learning from home to care for a neighbor’s ducks and chickens. A high school junior in Chicago recommitted to education and his love of physics after a 3 a.m. epiphany watching Neil deGrasse Tyson videos on YouTube. And a New York City senior who scoured her apartment building for a decent Wi-Fi signal discovered something better: her neighbors.

‘Returning’ to school

WELCOME TO PANDEMIC SCHOOL, YEAR TWO: For students starting a new school year, there are advantages to going virtual. An extra 45 minutes of sleep, for one. Not having to pack a lunch. Avoiding the disgusting bathrooms that are seemingly impossible to avoid in any building occupied by so many adolescents. But as Sadie Bograd writes, much is lost: “Going back to school simply didn’t feel like much of a meaningful shift after a similarly Zoom-filled and homebound summer.” Her school in Lexington, Kentucky, started the semester entirely online. But as she started school, moving from class to class, or link to link, she found several small reasons to be hopeful. Some teachers adorned their Canvas pages with virtual Bitmoji classrooms, their avatars guiding students to important links. Others went on fascinating tangents and rambling digressions. “In short,” Bograd writes, “my teachers’ personalities managed to come through the small box they occupied on my laptop, reassuring me that even without the possibility of face-to-face interaction, I’ll still be able to make meaningful connections.”

Pain and loss

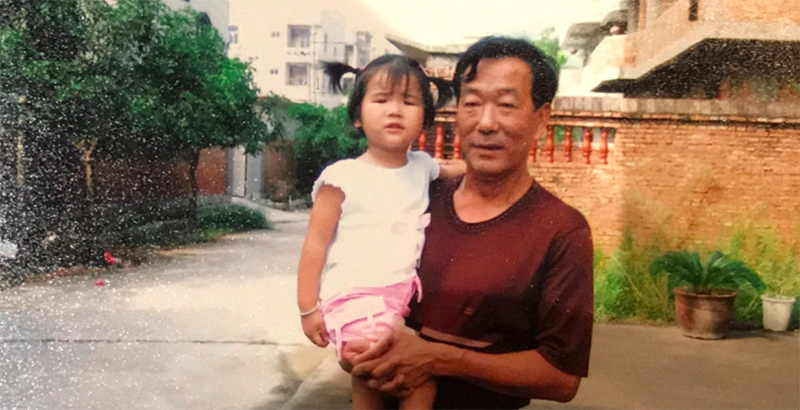

A GRANDFATHER’S DEATH & A MEDITATION ON COVID’S MENTAL HEALTH TOLL: “The day I found out my grandfather died, I cried so hard I threw up,” Cindy Chen writes. “Two days later, I went back to school.” When Chen’s parents, both Chinese nationals, tried to start a new life for their family in New York City, her grandparents raised her in China, where she lived until she was 5. It was her grandparents who “took me to the park, cooked my favorite meals and tucked me in at night.” She remembers mischievously hiding her grandfather’s cigarettes and how he’d chuckle and call her a “bed egg.” His death, a world away and during the pandemic, was devastating. “I walked through the front doors holding back tears,” the New Jersey high school junior writes. “It wasn’t that I felt uncomfortable crying in public. I just wanted to avoid combining a mask with a runny nose.” In this piece, she reflects on the pandemic’s mental health toll and how the effects have fallen harder on young people, like her, who suffered from loneliness and depression even before COVID-19.

DOMESTIC ABUSE DURING QUARANTINE: “For as long as I can remember, I was a bird trapped in a golden cage. On the outside, my world was a glittering array of debate trophies, academic titles, college scholarships and a picture-perfect family. But no one knew the fractured portrait that was my abusive household.” So begins one student’s story of coping with toxic parents as COVID-19 took away the safe haven of school. As of 2020, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 children reported being victims of domestic abuse, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — and the pressures of quarantine are likely to worsen those grim statistics. The author, who wrote anonymously out of concerns for her safety, said that like many teens who have been victims of abuse, being forced to stay at home was a prescription for danger: “In essence, my home life was a ticking time bomb.”

Trying something new

HOW NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON SAVED MY YEAR: Shortly after the pandemic began, Chicago high school senior Jimmy Rodgers “fully expected everything to just continue going downhill as the world made less and less sense.” The idea of being locked in the same room made him unimaginably depressed. The only time he got to leave the house was to bury his grandmother. But everything changed one day at 3 a.m., when he watched a video of astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson on YouTube. “I came to a startling conclusion,” he writes. “I was the person needed to solve the mysteries of the universe.” Tyson’s optimism and passion were infectious, Rodgers said, pushing him to do better in physics and commit himself to a career teaching and helping others in the Black community. “To my surprise,” he writes, “education gave me something to be happy about, rather than numb, at a time when all my days felt the same.”

FOR THIS FIFTH-GRADER, SCHOOL WAS FOWL: For Zora Borcila-Miller, a fifth-grader in East Lansing, Michigan, the pandemic has sometimes been lonely. Once, she got so bored she made a twin out of her clothes, a pillow and some broomsticks. She’s been learning remotely since the pandemic began, but when she and her dad moved to a new house in downtown Lansing, six blocks from the Capitol, she met her neighbor’s ducks and chickens. Zora describes the “hands-on and interactive” education she got while school was virtual. “When I’m at school, I’m usually on the couch with my computer,” she writes. “I have never talked to my teacher in person, only on Zoom. And it’s OK. But, in school, we never got to meet a duckling born the day before.”

Equity and privilege

COVID-19 RAISES STAKES FOR COLLEGE ADMISSIONS: Bridgette Adu-Wadier always knew she would enroll in college — the more prestigious, the better. But as the daughter of Ghanian immigrants, she didn’t always know how. For her family, education was the Way Out, she writes. “It was also a way to set a precedent for my younger siblings, lift my family up from poverty and potentially change their economic trajectory for generations.” The pandemic placed fresh obstacles in the way of that pursuit. Because of her parents’ work schedules, she had to homeschool her younger siblings. That, in addition to her rigorous academic routine, caused her to lose sleep. “I discovered a glaring similarity between college admissions and the pandemic,” she writes. “Both are difficult for everyone, but harder for some students than others.”

MASK CONFUSION, AND A LESSON ON PRIVILEGE: In May, high school senior Ianne Salvosa crossed the graduation stage at Liberty High School, outside St. Louis, and accepted her diploma. But the lessons she’ll be taking with her to college will go far beyond academics. The past year of fighting over mask requirements has left her with some uncomfortable feelings about her classmates. Students, many of whom openly doubted the efficacy of vaccines, fought with teachers over wearing masks. Long before vaccinations were commonplace, administrators frequently walked the halls with masks down. “Like all seniors who have lived through the past year, I understand burnout,” she writes. “But it appears our academic fatigue has seeped into our response to the pandemic.” The cavalier attitude toward masks, she said, “feels like some sort of show we put on so that the rest of the world can believe we did our part. It’s an ugly feeling I’ll take with me into college and beyond the current crisis.”

Making connections, finding love

SEARCHING FOR WI-FI, STUDENT DISCOVERED HER NEIGHBORS: When New York City’s schools went remote in March 2020, Ilana Drake was stuck. Knowing the strongest Wi-Fi signal in her family’s small apartment emanated from the front closet, she set up base camp in a common hallway outside, across from the elevator. Then a strange thing happened: She began to listen. “You can hear everything in the hallway,” she writes. “I heard snippets of conversation from nearby apartments: marital arguments, frustrated parents, stock trades, kids engaging in homeschooling and, of course, a symphony of barking dogs.” She also got to know her neighbors and the building’s staff. Drake has a learning disability and recently graduated from the city’s High School for Math, Science and Engineering. But in the hallway, she learned that everyone had some sort of “academic backstory,” including the neighbor who dreaded standardized tests and the service technician who had been an engineer in the Dominican Republic and helped her with calculus. “Working in the hallway,” she wrote, “provided me with a passport to conversations that went beyond ‘hello’ and ‘have a good day.’”

YOUNG LOVE IN THE TIME OF COVID-19: Ila Kumar remembers her pre-pandemic dating life with a whiff of nostalgia: the “charming absurdity of pretending you are older than you are, wearing itchy sweaters in bad restaurants, knowing the 15-year-old across from you is going to insist he pays for your slice of pizza.” Now, Kumar writes of the difficulties of navigating the tricky waters of teenage romance at a time of swiftly changing guidelines regarding masks and social distancing. “Maybe I forgot what it means to get to know someone — to uncover their secret talent for impressions, learn the way their hands move when they dance to music in the car and remember how they smell,” she writes. “Every corner of a relationship requires work, and the specter of something as small as unanswered messages, wanting eye contact and being left without it, and midnight arguments requires the singular power of trust.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter