Oklahoma’s Endorsement of Religious Charter Schools Could Alter Legal Landscape for Choice

If approved, an application from the Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City would establish the first religious charter school in the nation

By Linda Jacobson | January 9, 2023Oklahoma is set to become the first state in the nation to weigh the approval of a charter school that explicitly allows religious instruction, heightening concerns about separation of church and state.

The Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City plans to apply this month to operate a virtual charter, acting on a recent state legal opinion that says religious organizations shouldn’t be prohibited from doing so. The state’s Virtual Charter School Board could make a decision as soon as mid-February.

Advocates for religious charters said they began planning their strategy over a year ago as the conservative supermajority on the U.S. Supreme Court began to flex its judicial muscle. For the second time in two years, the court agreed to hear a school choice case and later sided with Maine families seeking to use tuition vouchers to attend religious schools.

“We’re not idiots. We know how things are going to play out,” said Brett Farley, executive director of the Catholic Conference of Oklahoma, which focuses on how public policy impacts the church. “We’ve looked at all the [school choice] options out there. Expanding charter options has always been on the short list.”

Even though it’s non-binding, the opinion from now-former state Attorney General John O’Connor and Solicitor General Zach West moves the discussion over religious school choice into a new arena. Recent Supreme Court rulings prohibit states from excluding religious groups from school choice programs. But allowing sectarian instruction in a public school, some legal experts say, goes too far. “Catastrophic” is how Derek Black, a University of South Carolina law professor, described it in a recent paper.

With charter leaders expecting similar moves in other states, some advocates worry the new direction could splinter a movement that has already drawn frequent criticism

“Public schools have never been able to, and cannot now, teach religion, require attendance to religious services or condition enrollment or hiring on religious beliefs,” said Nina Rees, president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Supreme Court precedent regarding public funding for private schools, she added, “simply does not apply to public charter schools.”

Farley said he expected that kind of opposition, but also sees “green lights all around for the movement to press ahead.”

In Louisiana, for example, charter leaders are watching to see what unfolds in Oklahoma.

“We’ve got large Catholic schools. We’ve got Pentecostals. We’ve got Baptists. We’ve got it all going on,” said Caroline Roemer, executive director of the Louisiana Association of Public Charter Schools. “Absolutely, we’ll see some applicants that lean in on that opportunity.”

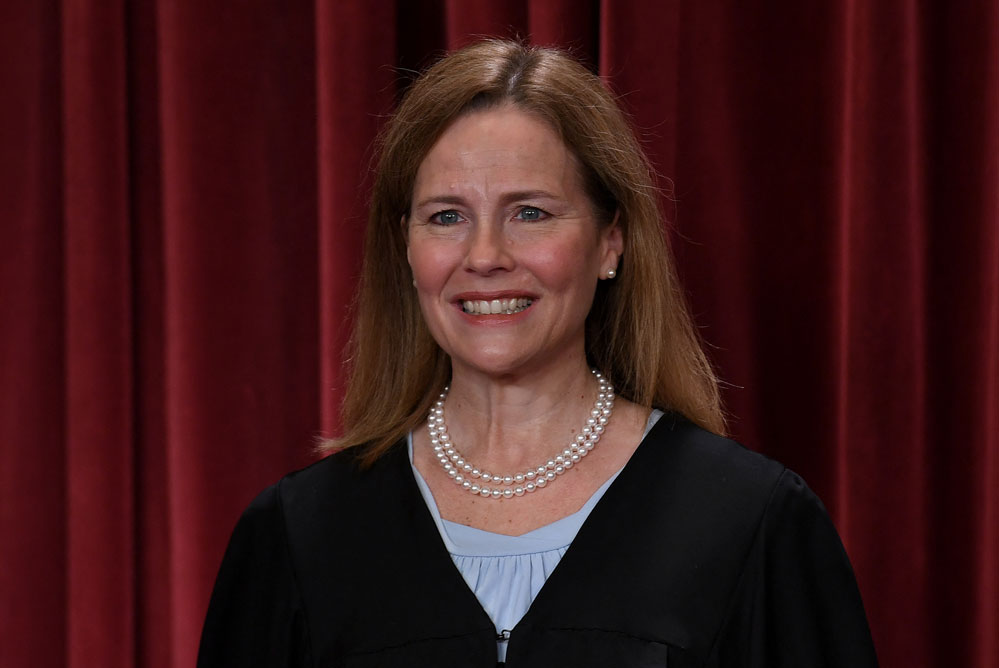

In Oklahoma, Farley said the archdiocese was further encouraged last year when it looked like voters would re-elect Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt, a fervent proponent of school choice. Farley consulted Nicole Stelle Garnett, a University of Notre Dame law professor and leading voice for religious charter schools. She is also a colleague of Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who taught at the law school.

That sparked the Oklahoma City archbishop’s November 2021 letter to the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board, asking if it would consider an application from the archdiocese. The board then sought the attorney general’s opinion.

While some Catholic schools around the country previously converted to charters, they only provide a secular education. For example, Barrett, a conservative Catholic, is affiliated with a church group that has helped launch charter schools. And some Hebrew language charter schools allow religious instruction in their afterschool programs. But Black said there’s a big difference between a faith-based organization running a secular charter — likely allowed under the Supreme Court’s rulings in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue and Carson v. Makin — and one that would, as Farley said, weave Catholicism into its entire curriculum.

What Farley describes, Black said, “does not involve discrimination based on religious status. Rather, it involves someone who wants to change public education into religious education.”

The U.S. Department of Education did not comment on the potential application.

Federal law says a charter school must be “nonsectarian in its programs, admissions policies, employment practices, and all other operations” and “not affiliated with a sectarian school or religious institution.”

Black said that, if approved, the archdiocese’s school would violate the Constitution’s ban on government support of religion.

“I don’t believe even this [Supreme Court] would say that is OK,” he said.

Farley countered there’s no such thing as a “values-free” education and that parents should be able to choose a religious or secular education for their child. A virtual charter, he said, would satisfy a growing demand for Catholic education, particularly in rural areas where parishes lack sufficient students to open brick-and-mortar schools.

‘In the name of the state’

The debate elevates the importance of a recent 4th Circuit Court of Appeals case that focuses on whether charter schools are public or private.

The lower court ruled that charter schools — even those run by nonprofits — act on behalf of the state, just like traditional schools. But Charter Day School in Leland, North Carolina, unsuccessfully argued that it had the flexibility to adopt its own dress code requiring girls to wear skirts. Families sued, saying the rule violated girls’ civil rights.

The school has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, and on Monday, the justices asked for an opinion from the U.S. solicitor general, who would argue the case for the Biden administration if the court accepts it.

Regardless of whether charter managers and employees work for nonprofit or religious organizations, the organization authorizing the charter is still “acting in the name of the state,” said Black, who sees the potential for “massive constitutional violations” if states allow charters that explicitly endorse religious instruction.

Oklahoma’s charter association said it is still reviewing the state’s opinion to determine its impact. The national Alliance, meanwhile, has a “legitimate concern” about backlash from blue states, where support for charters is already tenuous, Farley acknowledged. In fact, Black said if courts allow religious charters, states that don’t want them would have no recourse but to eliminate their charter laws.

“You could see states like Massachusetts, California or New York saying, ‘If courts are going to force religious charters on us, we will get rid of them,’ ” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter