Inside One of America’s First Catholic-to-Charter School Conversions: ‘Intentionally Small,’ Built Around Character & Thriving

Why Center City Petworth has deliberately kept its campus small to pair enriched curriculum with relationship-building and character development

By Emily Langhorne | January 8, 2019Washington, D.C.

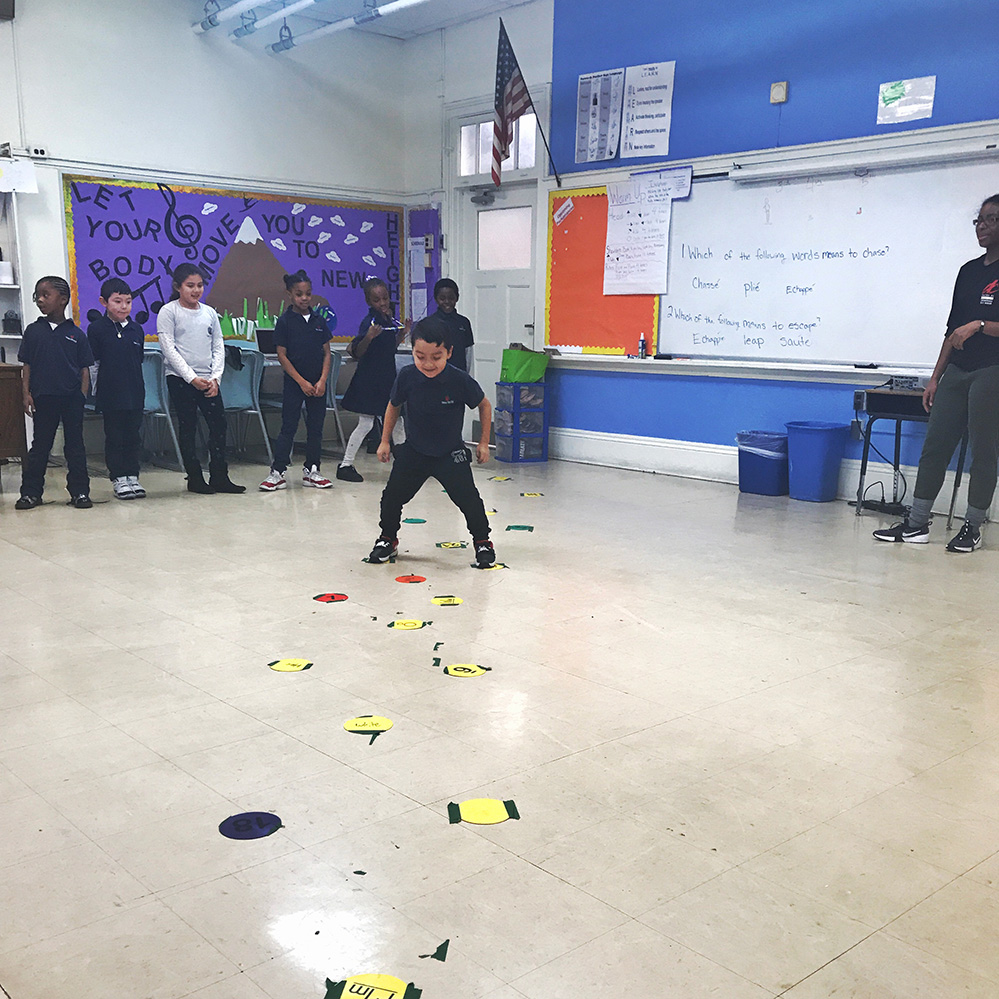

Three rows of second-graders stand facing the front of the classroom. A speaker emits sounds. First, a door creaking. Then, footsteps thudding and a wolf howling, all followed by the unmistakable opening riff of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

The students put their hands on their knees and take four big steps forward before swinging their arms quickly from side to side. When they’ve finished performing this simplified version of Jackson’s choreography, many fall to the floor, giggling.

Jordan Daugherty teaches dance at Center City Public Charter School’s Petworth campus. Today, her second-grade class is learning the difference between improv and choreography.

“That’s great,” Daugherty says. “Now face me upstage. That was choreography. Remember, improv is when you feel the music and move with it. Choreography is when you make up the moves in advance to match the song.”

At Center City Petworth, all students take dance year-round as a part of their regular schedule. It’s an enrichment course, along with STEM and physical education, all components of the school’s commitment to providing every student with a comprehensive education.

“We believe that we need to develop good citizens and well-rounded people, as well as scholars,” says Principal Nazo Burgy. “To do that, our students need to be socially and emotionally healthy. Play is really important to early childhood, and this is a place where kids can be kids. We have schedules, procedures, and routines, but our hallways are not silent.”

Center City Petworth is part of Center Public Charter Schools, a network of six intentionally small schools operating in four of D.C.’s eight wards. Each school has between 200 and 270 students in grades pre-K through eight and only one class of about 25 students per grade.

The Center City network began when a group of private Catholic schools, experiencing financial problems, was on the verge of being shuttered. Many of these schools, like Petworth, had occupied an important place in the community for nearly a century.

“Families wanted the school to survive,” says June Felix, a kindergarten teacher at Center City Petworth and the last remaining teacher from the school’s era as a Catholic institution. “Teachers and parents rallied behind it becoming a charter school.”

In 2008, as part of the first Catholic-to-charter school conversion in the country, the Petworth campus, along with five other Catholic schools, became Center City Public Charter Schools.

“It’s been a great change,” says Felix. “As a Catholic school, we could not take all students. Our community had started to change, and community members who wanted to come to our school couldn’t afford it. We didn’t have the funding to help students with special needs, either. As a charter, we can serve all of them.”

Today, Center City Petworth’s student population is approximately 45 percent Hispanic and 46 percent African-American, with 60 percent of students designated as economically disadvantaged. Currently, 25 percent of Petworth’s students are English language learners, a number that has been increasing each year.

“Our schools are like small neighborhood schools, so they mostly reflect our local community. Our size and the supply and demand of the school lottery, as well as the sibling preference, influences that,” says Alicia Passante, Center City’s ESL program manager. “At Petworth, almost all of our Spanish-speaking students’ families come from El Salvador. We also have a lot of families from Ethiopia and the Philippines.”

After the conversion, the schools’ new leadership removed all religious elements, but they decided to keep the schools small so that teachers could continue to emphasize character development and relationship-building, in addition to providing a high-quality educational program.

For the past three years, the D.C. Public Charter School Board has awarded Center City Petworth a Tier 1 ranking. Although the overall percentage of students scoring at or above proficiency on state exams is on par with the average score for all D.C. public schools, a larger percentage of the school’s “at-risk” and Black/African-American students achieve proficiency than the district-wide average, according to the Office of the State Superintendent of Education’s newly released school report card system. In addition, Center City Petworth boasts a higher in-seat attendance rate, a higher re-enrollment rate, and a lower rate of chronic absenteeism than the district-wide averages.

Following the script — and not following the script

“Because of our size, teachers really get to know students,” says Hannah Groff, the schools’ language access coordinator. “They watch them grow up from kindergarten. Often, they know the family well before they even teach a student, and they often teach siblings.”

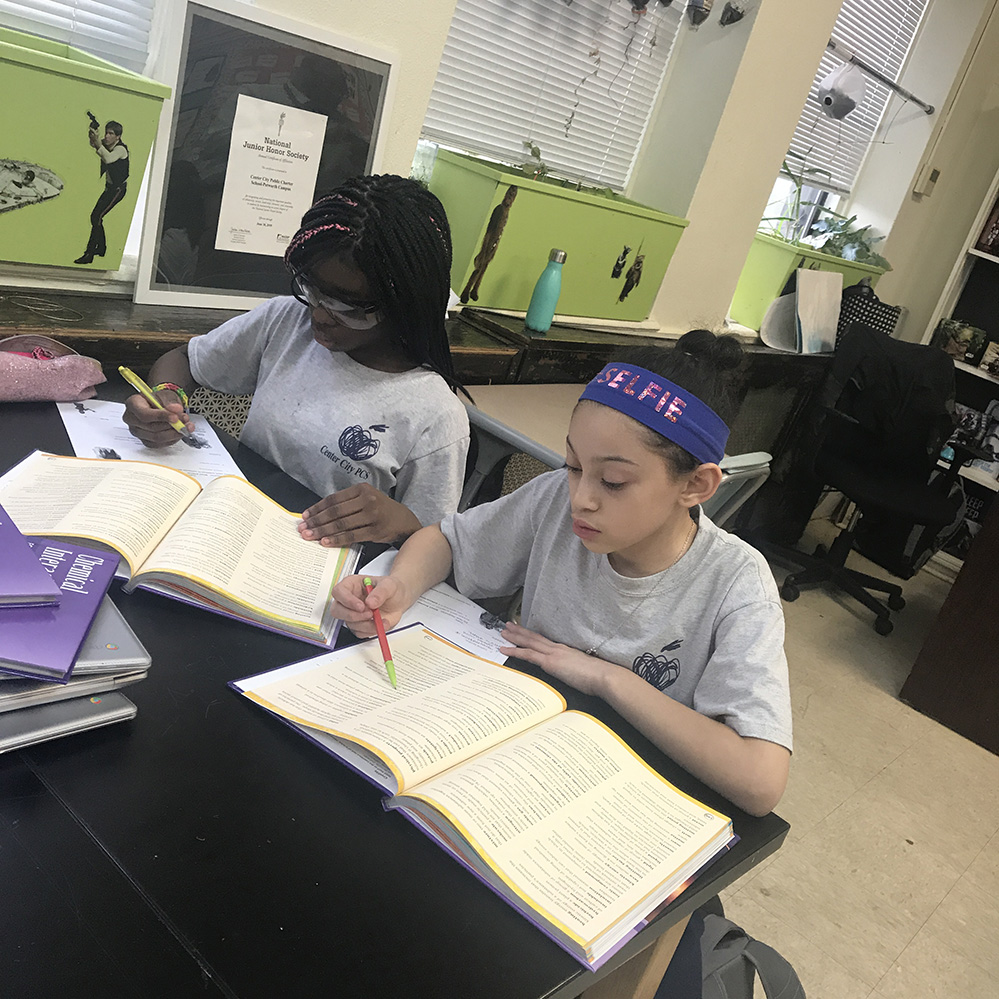

Center City Petworth prescribes Common Core-aligned curricula and materials for teachers, like Wit and Wisdom, a K-8 English Language Arts curriculum that emphasizes writing, language, speaking, and listening standards by focusing each unit on an essential question and thematic text set, and Eureka Math, a pre-K–12 curriculum that stresses daily fluency lessons, conceptual learning, and rigor. While the units and day-to-day lessons are provided, teacher creativity is still valued.

“We want teachers to follow the script and not follow the script,” says Passante. “For instance, Eureka Math was too advanced for many of our kids at first, so teachers had to find creative ways to scaffold it. And Wit and Wisdom is a very rich curriculum, but it needs hooks for student buy-in, and hooks come from teacher experience. They’ve got to make it their own by bringing their personalities into it.”

Because of the low teacher-student ratio, students receive a lot of individual attention. Pre-K to first grade is self-contained, taught by a lead teacher and instructional aid. In upper elementary school, teachers have looped classes — they teach the same students for two grades. From second through fifth, students take humanities with one teacher and math and science with another. In middle school, teachers teach all three grades, and there’s both a science and a math teacher. For all grades, the content area teacher usually co-teaches with an inclusion teacher, who specializes in English as a Second Language or special education, depending on the needs of the students in the class.

“There’s pros and cons to every teaching model,” Passante says. “The pro here is that teachers become masters in their content area, but it’s a lot of work because they prep for multiple grades. The big pro for our students is the building between grade levels. When a second-grade teacher also teaches third grade, that teacher knows exactly where the students need to be standards-wise at the end of second grade to be successful next year.”

Teachers also chose what electives the school offers. Middle school students take a different elective each quarter, usually choosing from three or four offerings. This quarter, some students are taking tap dance while others are taking robotics, where they use Lego Mindstorms kits to build and program their own robots. During the first day of the art elective, P.E. teacher “Coach Sam” Daniel taught students about the minimalist line drawings of Pablo Picasso before they created single-line drawings of their hands, in pen, so that they couldn’t erase. Teachers have to be informed about their elective subjects but not necessarily experts in the subject matter.

School leaders also encourage teachers to make time for their “passion projects.” Fifth-grade humanities teacher Shannon Nuzzelillo loves animals, so she partnered with the Washington Animal Rescue League to provide kids with volunteer opportunities. Her students have learned how to approach animals, and they’ve also practiced their reading skills by snuggling up with, and reading aloud to, a canine friend.

Middle school science teacher Mark Joyner’s classroom is decked out in Star Wars memorabilia. A bookcase behind his desk is filled with action figures. Stickers of C-3PO, R2-D2, Boba Fett, and others cover bulletin boards. At the beginning of the year, he asks students to decide whether they want to join the Light Side or the Dark Side. Then the battle begins. Each day, they compete in “Science Wars”: trivia questions based on the week’s lessons. A drawing of light sabers on the wall, with a scale ranging from Sith apprentice to Sith Lord and Youngling to Jedi Master, marks whether the Light Side or the Dark Side is the week’s winner. Joyner’s love for Star Wars is apparent throughout his classroom, except for the turtles. They are named after the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles; he let the students pick those.

Strengthening the small school community

“Being a small school is a blessing and a curse for students,” says Principal Burgy. “Everyone gets to know each other very well. The downside is you’ve got to learn to get along with your peers even if you don’t like someone very much. We focus a lot on social and emotional learning to help strengthen our community relationships.”

Each morning begins with a school-wide, student-led meeting. The students play games, talk about character, and practice mindfulness. Each week, the meetings emphasize a different virtue that benefits the community, like patience, generosity, and honesty. Every Friday, school leaders honor a student who demonstrates that week’s virtue.

Each grade also has monthly socio-emotional lessons. Fourth-graders recently had a lesson on “thinking before speaking” while fifth-graders focused on self-regulation and calming strategies, such as deep breathing, getting a drink of water, and internal counting.

Because it can be challenging to have 3-year-olds and 13-year-olds in the same building, students participate in a “little buddies” program to promote cross-grade community. The older students partner with younger students as reading buddies, and together they read a book one month and then complete a project on it the next. At the end of the school year, they also work together on a school beautification project, such as painting the playground fence or creating a mural for the hallways.

“The ‘little buddy’ system helps us improve our social interactions with the younger ones,” says eighth-grader Chelsea Lazo. “It makes me happy. I like how we get to teach them and help out the community. It makes me think that when I grow up, I might like to do something where I help others.”

Her classmate, Nash Campo, agrees. “Even by reading with someone, I can build small relationships, and it helps me get to know my community better,” he says.

Staff members also conduct home visits to strengthen relationships with students and families. For the 2018-19 school year, the staff’s goal is to conduct a home visit to 90 percent of families. Lazo thinks that home visits are especially helpful when a new teacher or student comes into the community. “My mom felt relieved after the new teacher visited because she got to know her and felt better about sending my little brother into her class,” she says.

“Parent buy-in is the first big outcome. I can see that many parents feel more comfortable,” says Mike Bailey, a first-grade teacher and leader of the school’s family engagement program. “Once they see we have the best intentions for their children, they trust us. Once that trust is built, then we can work together to grow the child.”

Throughout the year, the school has many events — cultural heritage nights, family potluck dinners, a visit to a pumpkin patch, family breakfasts, and more — that they encourage parents to attend.

“Parents become really trusting of this school because of the small community,” says Groff, the language access coordinator. “If they have issues, even when they aren’t school-related, this school is often the first place they come because they feel safe saying, ‘I need help.’”

“My parents, especially my mom, really like this school,” says Campo. He began attending Center City Petworth in second grade when his family moved to the U.S. from the Philippines. “It took awhile for me to speak English, but my teachers were supportive. Over time, my parents got to know everyone at the school — all the teachers and staff — because everyone is really kind. In fourth grade, I had a mild stroke, and Ms. Burgy was really helpful. She took me to the hospital and explained everything to my mom, so she wouldn’t panic.”

The challenge of saying farewell

The transition from the small environment of Center City Petworth to a large-scale high school can be difficult, but the school’s staff works with students so that they’ll know what to expect.

“We really teach our kids how to be their advocates because we know that they’re used to this small school, and that high school could be a rude awakening for them. We hope that by teaching them to advocate for themselves from the start, they’ll understand how to use their voice to get what they need to be successful,” says Passante.

Eighth-grade students have a high school prep class each week with a counselor. The counselors work hard to assist students with getting into the best schools. They do research to match GPAs and test scores with selective and private school requirements to figure out which schools they’re eligible for. The students go on shadow visits to schools where they shadow other students, which helps them find schools where they’re a good fit. Each student applies to five schools through the class. Students participate in mock interviews with counselors. They write application essays and, for private schools, complete scholarship applications.

“It’s nerve-racking,” says Lazo, who hopes to attend either The School Without Walls or Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School next year. “All the applications and the essays, wondering if and where you’ll get in, but it’s also good because when you apply for high school, you’ll get used to how it feels and what to do when you apply for college.”

Counselors also work with families to help educate parents on why a convenient neighborhood school might not be the best option for their child. Many parents don’t like the idea of sending their son or daughter to a school outside the local community. Often counselors have to explain to parents why taking a bus for 40 minutes to a school across town will benefit their child in the long run.

“Our goal is to send 80 percent of our students to Tier 1 charter schools, private schools, or highly selective DCPS schools. Last year, we were just shy of that, with 76 percent,” says Passante. “In general, we try to steer our kids away from the neighborhood high schools, but some do go there and are successful.”

Most students are excited about the prospect of starting high school, but they also realize that they’ve been fortunate to have such a homey environment during their early school years.

“Everyone here is a part of my second family,” says eighth-grader Ashley Velasquez, who has been attending Center City Petworth since kindergarten. “Everyone is so open, and the teachers are there whenever you need them.”

Campo agrees: “Years from now, I’ll still remember how we were like a family here.”

Lead image: Thomas Nebyou (second grade) practices his leap in dance class at Center City Petworth (Courtesy Center City Public Charter Schools)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter