Number of Districts Safe for In-Person Learning Shrinking, New Study Suggests

As the pandemic continues to surge, fewer and fewer school districts may have community coronavirus levels that are low enough for safe in-person learning, a new study suggests.

Last week, a team of researchers from Tulane University released a paper examining the effects of school reopenings on COVID-19 hospitalizations. Their study, using national data, identified a threshold — 36 to 44 hospitalizations per 100,000 people per week — below which opening schools did not increase levels of community virus spread. Above that level, however, the researchers could not rule out the possibility that in-person learning might spread COVID-19, and another recent study found that reopening schools in such areas does tend to increase caseloads.

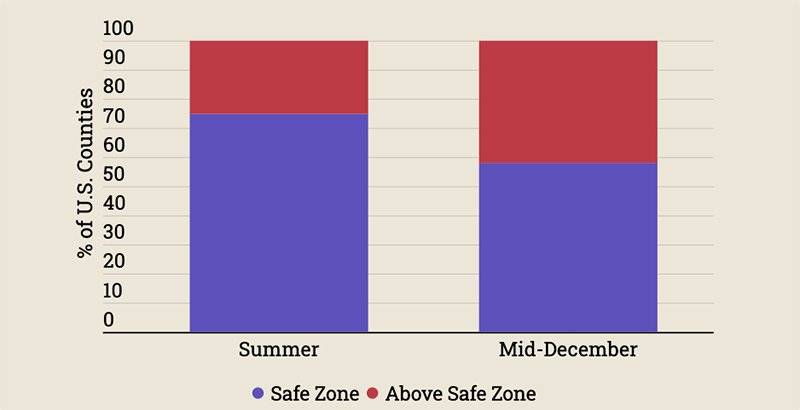

When it was published, the study from Tulane used data from this past summer to estimate that roughly three-quarters of U.S. counties fell below their marker for safe in-person learning. But that was months ago, and now the share may be significantly lower.

“As of mid-December … 58 percent of counties were below that threshold, so in the safe zone,” Douglas Harris, a professor at Tulane University who co-authored the study, told The 74.

His re-calculations were not published in the study, but reflect national increases in coronavirus spread. As caseloads rise, the needle has moved on the number of counties that fall below the 36 hospitalizations per 100,000 people per week marker that his team identified. In nearly 20 percent of counties, illness levels have risen above the “safe zone” since the summer, Harris’s new numbers suggest.

To help local decision makers determine whether it’s safe to open schools in their area, Harris and his team created a searchable spreadsheet, which provides hospitalization rate data for every county in the country and can be compared to the Tulane study’s threshold.

Still, Harris cautioned officials not to use the benchmarks he and his team published to decide whether or not to open schools without also considering other factors. There’s a danger in relying on the “magic number,” he said, because variables such as masking and distancing policies, ventilation in school buildings, and contact tracing can also help determine whether in-person learning is a safe option.

“We’re not saying schools below the threshold should open. We’re not saying schools above the threshold should stay closed. There are other considerations here,” said Harris. “How you reopen is just as important as whether you reopen.”

Benjamin Linas, an associate professor of epidemiology at Boston University, echoed this sentiment, underscoring that it’s much easier to enforce rules preventing transmission in schools than in businesses, such as restaurants and gyms.

“Schools are a well-controlled environment and if you put mitigation in place, you can control COVID spread,” Linas said. “The last thing to close should be your schools and the first thing to open should be your schools.”

The BU epidemiologist thinks officials should make decisions about whether or not to open schools based primarily on their capacity to mitigate risk, rather than on levels of community spread. Prominent districts such as New York City, Detroit, and Chicago have upset families and teachers by continuing in-person learning after surpassing their pre-specified COVID-19 positivity rate cutoffs.

“It’s bound to do damage if you basically shift the goalpost too many times,” Linas said.

In a recent press release, the Chicago Teachers Union cited the Tulane hospitalization study in protest of the district’s plan to move forward with in-person learning. In New York City, despite randomized testing from December that revealed only a 0.68 percent virus positivity rate in schools, teachers objected to the decision to keep schools open after the city last week surpassed its 9 percent positivity threshold.

“If the community infection rate in the city hits 9 percent, the safe thing to do is to close the schools, even if the in-school rate is lower,” said United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew. “Safety comes first — as shown by the fact that hundreds of our elementary schools and classrooms are closed temporarily every day because the virus has been detected. That is how we have stopped the spread of the virus inside our schools.”

But as teachers unions, school officials, and families eye the percentage of positive COVID-19 tests, Harris and his co-authors approach the issue from a slightly different angle. The Tulane study differs from many other reports on school reopenings in that it examines hospitalization rates as opposed to virus positivity rates, which are problematic because the amount of precautionary testing a locale carries out can impact the percentages.

“Hospitalization reflects sickness,” said Harris, explaining why that datapoint might be a better measure for the real impacts of the coronavirus, which as of Jan. 11, had infected 22.4 million people in the U.S. and killed 374,428 people. On that day, there were 129,229 hospitalizations.

Still, even though Harris’s study raises doubts about whether areas where the virus rages are safe to open schools, he underscores that decision makers must also weigh the social and health impacts of shuttering schools.

“Even if there is a trade-off, even if it does have some risk of spreading the virus when students go back into school, there’s also a cost to keeping them closed,” said Harris, pointing to reports of mental health issues for youth, malnutrition, and severe learning loss during virtual school. Currently, 53 percent of American students are attending online-only schools, according to the most recent update from the website Burbio, which tracks school reopenings.

“We tend to focus on the immediate effect which is, you walk into school and you give the virus to somebody else and it then spreads,” said Harris. “But I think we have to think about the other public health crisis [that] involves all these other indirect effects of keeping schools closed.”

Even in light of a new, more transmissible strain of the coronavirus, which Linas calls “concerning,” the epidemiologist advocates for officials to mitigate risk and keep schools open, where possible.

“The benefits of school are huge,” he said.

With many reopening plans pinning their hopes on new vaccines, and with calls from teachers unions for educators to be among the first to receive vaccinations, he believes it should be a top priority for teachers to get the shots, right after doctors and health care workers.

“If we’re going to say that schools should be the last to close and the first to open, then teachers should be right up at the front of the line for getting the vaccine,” Linas said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)