Hunger Pains: Keeping Kids Fed During the Pandemic Stretches the Limits of Bureaucracy

In mid-October, at a warehouse on the East Side of San Antonio, 600 large green bins filled with food sat for weeks waiting to be delivered to children in some of San Antonio’s poorest schools.

The bins were yet another image of hunger during the pandemic and the numerous bureaucratic blockades keeping meals from hungry kids—waivers and protocols that mean little to the families wondering if dinner will be on the table.

The holdup wasn’t just affecting the green bins, which belonged to the nonprofit SnackPak 4 Kids of San Antonio. All across the country school districts had been shuffling and reshuffling the pieces of a complicated, ever changing puzzle, trying to get food to kids.

Weeks later, many of the wrinkles had been ironed out, as school and nonprofit officials managed to cobble together a fragile delivery system to cover three meals per day and weekends for kids who need it. Most kids, it seems, not all.

But with neither COVID-19 nor child hunger going anywhere any time soon, nonprofits and districts worry the fragile system and constant changes to it will result in more hungry kids. They want a longer term solution.

“Schools must be provided the resources to make available a meal to every child who needs one, not only until a vaccine is widely available, but until our economic conditions improve substantially,” said Brian Woods, superintendent of Northside Independent School District, San Antonio’s largest.

“It’s been a nightmare,” said Melanie MaGuire, director of programs at the San Antonio Food Bank, which supplies meals to afterschool programs. “The regulations just keep changing.”

This is the story of how delayed waivers, complicated regulations, and rigid district protocols hampered San Antonio’s efforts to feed its chronically hungry children — a scenario that could play out again.

The First and Constant Need

When schools closed in March, the first concern for many educators was not online learning. It was food.

“Food insecurity raised its head immediately,” said Woods. Many San Antonio students eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner at school. While they are there, nonprofits like SnackPak 4 Kids get weekend meal bags with packets of crackers, cereal, and peanut butter into their backpacks to help with hunger over the weekend.

Teachers are trained how to identify food insecurity—cracked lips, rushing cafeteria lines, extreme hunger on Mondays, and puffy skin are among the symptoms.

Families who were already strapped found themselves with more mouths to feed at home as relatives moved in. Kids stayed home, and lost jobs meant less income to make ends meet. A study conducted by the University of Texas at San Antonio’s Urban Education Institute found that 26 percent of families with children said they had experienced food insecurity—they had run out of money without being able to buy the food they needed at some point in the pandemic.

Soon after schools closed, San Antonio’s food insecurity was graphically illustrated by a breathtaking aerial photo of thousands of cars lined up outside a San Antonio Food Bank distribution event. The image has become famous for illustrating skyrocketing food insecurity in the city and around the country.

Since then, the Food Bank has distributed over 29.8 million pounds of food since March, to 120,000 people per week. They reported that 35 percent of their clients are children. A food pantry run by Catholic Charities of San Antonio went from serving less than 100 people per week to over 1,000.

Schools were feeling the impact of increased demand too, and had to adjust their services.

In March, the USDA quickly provided waivers to allow more flexibility getting food to kids who were at home — a significant move for a federal agency that highly regulates the National School Lunch Program right down to detailing nutritional components of meals, where they can be distributed, and to whom.

Additionally, in the three to four weeks immediately after school closures, donors flooded SnackPak 4 Kids of San Antonio with money, said volunteer executive director Leslie Kingman, allowing them to distribute 6,000 bags of food per week—more than double their pre-pandemic distribution— to any family picking up a meal at a school where SnackPak operated.

School districts continued providing breakfast, lunch, and bags of weekend food throughout the summer, as they usually do, using a USDA waiver allowing districts to offer meals for breakfast, lunch and weekends to any child.

But when school started up again in August, the whole system had to be rebuilt.

Starting from Scratch

Schools were still working to be part of the hunger solution, Woods said, but the variables were changing constantly.

USDA officials did not initially renew a waiver allowing weekend meals, snacks and dinner to be served at the same school. Normally, such combinations are prohibited to prevent students from double dipping on meals. But when the need for food exploded at the start of the pandemic, the USDA freed schools to use every program they could.

Once the waiver was not renewed and the strict rules went back into place, the confusion it created for families became evident quickly: Northside was serving about 4,000 fewer meals per day in September than it had in April.

“We have changed the rules on families so many times that it’s no wonder they don’t know how to pick up a meal,” said Woods.

After school had been in session for a month, the USDA allowed supper, snacks, and weekend meals to be served simultaneously again, pushing more food into the school delivery pipeline.

The USDA did not return requests for comment in time for this publication.

Moving Targets

But even with the waivers back in place, meal distribution is more complex now than it was in the spring SAISD Senior Executive Directory of Child Nutrition Services Jenny Arredondo said.

With some students back in the building, her team is now essentially running two separate programs. “We’ve got to keep them separate for the simple reason that we cannot duplicate meals,” she said.

The USDA requires school districts and nonprofits to make sure kids aren’t getting the same meal twice—once in school and once at the curb.

With each waiver and each group of students brought back, Arredondo must constantly balance an impossible equation.

On one side, images of thousands of cars with hungry families lined up for Food Bank boxes. On the other, making sure her department complies with federal regulations.

Strained Partnerships

SnackPak, meanwhile, is still trying to establish a system for its new normal.

At some schools, COVID-19 safety protocols completely halted SnackPak’s operations. For those kids the bins of food in the SnackPak warehouse stayed as neatly lined up as the cars waiting for food.

In a normal year, the jars of peanut butter, cereal bars, and other shelf-stable food items would have been distributed to 2,500 students in four San Antonio school districts.

SnackPak’s army of church and Rotary Club volunteers purchase, assemble, and distribute the bags of food on Thursday evenings. Teachers discreetly slip the bags into the backpacks of the kids they’ve identified.

That process, designed to minimize extra work for teachers and maximize privacy for children, has been completely upended by COVID-19 when the volunteers who packed the bags were not allowed on campus.

Still, in the midst of the restrictions, some districts have found a pandemic-safe way to get SnackPak back into their buildings in an effort to plug more of the gaps in the USDA programs. They want to keep the program going, Kingman said, because once the pandemic has passed and school goes back to normal, kids will still need weekend meals.

“There’s not a school in Bexar County that doesn’t need a weekend meal program,” said Kingman.

At Oak Grove Elementary in North East ISD, family specialist Elizabeth De La Rosa was disappointed when her office was moved to an otherwise empty portable building away from the rest of campus.

Now, she says the move was providential. She is using the extra space to store the bins dropped off by Snack Pak volunteers, who cannot enter the main campus. She and the school nurse distribute the bags of food discretely to classroom teachers, a task usually done by the volunteers. It’s extra work De La Rosa said, but she and the nurse are glad to do it.

“It’s so worth it,” she said, “Our families need it.”

In schools where staff have not been freed to enlist the help of their colleagues, parents have stepped in.

In the spring Becky McMains, a parent at Lamar Elementary in SAISD, started running a food pantry out of her garage, using food donated by members of her church, Grace Northridge. She and a few others would pack the food into boxes and take them to wherever SnackPak bags were being assembled and taken out for delivery directly to kids’ homes, another emergency provision of the program. Eventually SnackPak assembly and the food pantry both moved into the church.

When SnackPak stopped for the summer, the food pantry kept going.

“We have parents who are anxious about this going away,” McMains said.

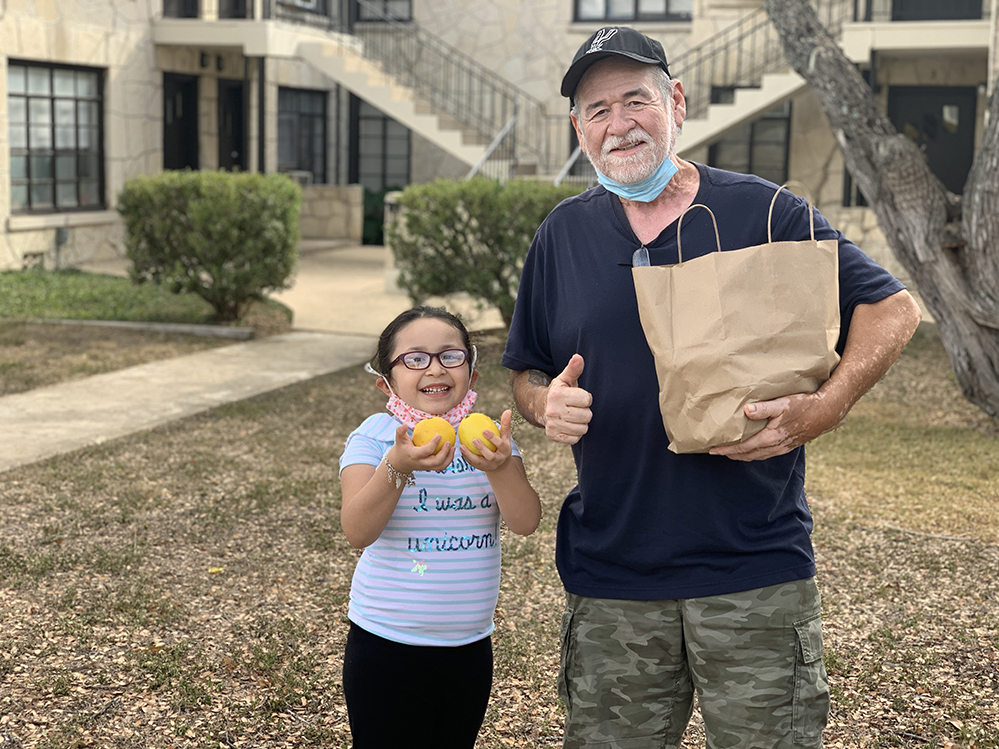

Vincent Luna, a single grandfather raising three kids, supplements his grocery list with food from the pantry at Grace Northridge. Not only does he get his own food, but he and his grandkids collect food for six other Lamar Elementary families. He does the same for four families at his own church using another food pantry in town.

“Some of them don’t have vehicles to get to the food so I deliver to them,” Luna said. “They would be in a really bad spot without it.”

While checking on the families, he asks them to give him any food they won’t use so he can redistribute it, he said. “I try my best to work it so nothing goes to waste.”

At some schools in SAISD, Communities in Schools staff are doing what they can to get some SnackPaks distributed. Every campus is different, and some still haven’t found a solution.

Kingman worries about the students who aren’t getting their SnackPaks. She’s working on a way to have the food distributed to kids over Thanksgiving break. The ones whose granola bars and beef sticks are still in the green bins, lined up in the warehouse.

“Those kids,” she said, “are written on our hearts.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)