Eric Adams Declared Winner of NYC’s Mayoral Primary, After Race Marked By Striking New Posture on Charter Schools

Updated July 7:

After multiple rounds of vote tabulation triggered by New York’s new ranked-choice voting system, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was declared the winner of the Democratic primary on Tuesday. With all other candidates eliminated, Adams edged past former sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia by a margin of roughly one percent. He is now seen as a heavy favorite in the November election against Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa.

With early voting already underway in the New York City mayoral primary, a question hangs over the nation’s largest school district: How will the next administration help schools get back to business after multiple academic years have been profoundly jolted by COVID-19?

Whoever emerges as the party’s nominee will face a multifaceted challenge in leading New York’s school system. After a lengthy period of serving as mayor-presumptive (Democrats massively outnumber Republicans across the city, making November’s general election a likely rout) he or she will need to complete the transition back to in-person schooling, carefully steward billions of dollars of federal relief money, and help students recover from nearly two years of learning interrupted by the pandemic.

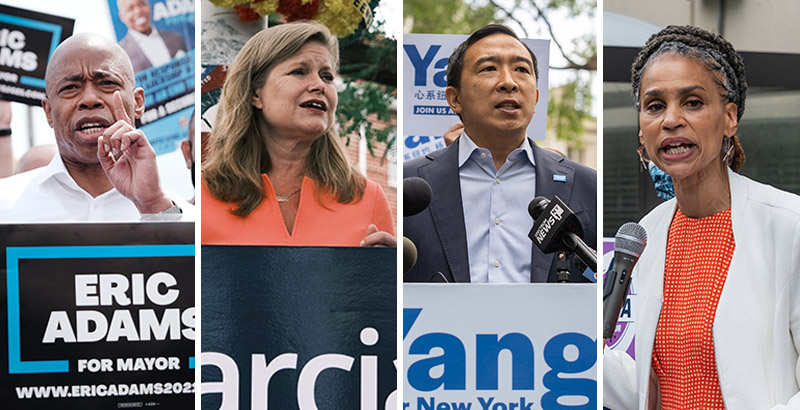

And there’s a further plot twist: Charter schools, perhaps the most controversial force in citywide education politics, have won the backing of most of the field’s leading candidates. Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, entrepreneur Andrew Yang, and former city sanitation chief Kathryn Garcia have all signalled some degree of support for the public schools of choice, which have seen their allies dwindle both in City Hall and Albany over the past few years. At the same time, one of the most strident charter critics, Comptroller Scott Stringer, struggled to build momentum even before his campaign was rocked by allegations of sexual harassment.

It’s a situation that upends the political logic of much of the last decade, when Democrats across the country have increasingly broadcast their skepticism of the sector, even to the point of proposing full-on moratoriums on new charters. Now, in a city almost synonymous with liberal politics, most of the party’s top mayoral contenders appear to be taking the opposite tack. The causes for the shift are multiple, including the relative popularity of charters among minority voters, a traffic jam in the primary’s progressive lane, and families’ dissatisfaction with the district throughout the travails of the pandemic.

Michael Mulgrew, president of the United Federation of Teachers, said in an interview that charter schools and their allies are exploiting a hectic post-COVID environment in which K-12 education has taken a backseat to issues of public safety and economic hardship.

“Crime is on the rise, we’re coming out of the pandemic, homelessness is exploding,” Mulgrew argued. “There are so many other issues that are facing people. If this election was last year, when education was at the forefront…this phenomenon would not have happened.”

But according to Richard Buery — a former deputy to incumbent Mayor Bill de Blasio who served briefly as the CEO of the Achievement First charter network before announcing Wednesday that he would leave to head the Robin Hood Foundation — it’s entirely unsurprising to see Democrats talking openly about supporting and expanding charters.

“Charter schools are incredibly popular among the Democratic electorate,” he said. “The distinction between a charter school and a district school does not fundamentally matter to most people. What people are interested in is whether they have access to quality schools for their children.”

De Blasio backlash

The 2013 election of Bill de Blasio marked a turning point on school choice in New York. After years of enthusiastic support from Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, both Republicans at the time they were elected, charter schools faced a Democratic mayor who openly vented his frustrations with them.

It began in de Blasio’s first few months in office, when he attempted to block three schools in the high-performing Success Academy network from co-locating in district-owned facilities. He was outmaneuvered by the schools’ allies in Albany, including Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who quickly signed a law guaranteeing charters the right to use space in public buildings. But the new mayor’s position was clear, and he has largely stuck to it throughout the remainder of his two terms in office — including telling an audience at the National Education Association’s annual assembly that his fellow Democrats needed to be held accountable for being “cozy with the charter schools.”

It was a stance that caught on throughout the party and only gained steam after President Donald Trump appointed longtime school choice advocate Betsy DeVos to lead the Department of Education. Though he had previously served in the Obama White House during a rapid surge in charter growth, then-candidate Joe Biden had little good to say about charters while winning the Democratic presidential nomination last year.

All of which makes the current configuration of mayoral candidates somewhat surprising, at least from the perspective of K-12 schools. Yang, who polled in first place during earlier portions of the race before fading somewhat — has contributed large sums to a charter organization in the past. While he reportedly favors unionizing charters, Adams also told a union audience that he would support the duplication of successful charter models. And Garcia has even suggested lifting the cap on charters in New York, currently set at 290, dismissing the debate around them as a “political football.”

Those positions haven’t gone unnoticed. Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, said she was “incredibly disappointed” with Garcia’s proposal. And Scott Stringer, who has sought to audit charter networks during his time as city comptroller and secured the nomination of the UFT in April, has pointedly attacked several charter-friendly financiers for making huge donations to political action committees that support Yang and Adams.

But the criticism hasn’t paid off so far. A familiar face in New York politics who many believed to be the front-runner among progressives when the race began, Stringer has failed to gain much altitude. Of the field’s top tier, only Maya Wiley, a civil rights attorney who worked in the de Blasio administration, seems to be generally running to the left on K-12 issues; even she is focused more on racial segregation and lowering class sizes than school choice.

No single candidacy showcases the frustrations of the progressive anti-charter movement than that of Dianne Morales. The experienced nonprofit executive had long been a proponent of school choice before pivoting leftward during the primary; her current platform includes proposals to end co-locations and prevent charters from accessing student recruitment data. But just as her campaign was gaining attention, it imploded amid allegations of mismanagement and discrimination. And as the primary is in its last gasp, Adams, Garcia, and Yang make up three of the top four candidates.

The UFT’s Mulgrew said plainly that he believed the turn on charters was the product of campaign contributions. A persistent critic of former Mayor Bloomberg, who worked energetically to spread more school options throughout the five boroughs, he argued that Wall Street donors who played an outsized role in charter expansion a decade ago were now hoping to control the debate again.

Bloomberg “had partners who financed so much of this, and we see these same people emerging again and being part of our political process right now in the mayor’s race through various IEs [independent expenditures] and different relationships,” Mulgrew said. “We feel very strongly that a small number of people who have a lot of money should not be influencing us.”

‘A huge disrespect to parents’

But support for charters doesn’t merely come from the financial and philanthropic realms. An April poll showed that a strong majority of New York City Democrats approved of lifting the charter cap. And while it was commissioned by StudentsFirstNY, a pro-charter advocacy group, its findings are mostly consistent with existing survey evidence demonstrating the popularity of schools of choice, particularly among the non-white New Yorkers who will play a role in choosing the Democrats’ nominee.

Families have already begun voting with their feet during the COVID era, with public data showing that charter school enrollment grew by roughly 10,000 students — about 7 percent — over the 2020-21 school year. While charter and traditional schools both spent long periods closed to in-person learning while the pandemic raged, the stop-and-start reopening process led by the district left many feeling dissatisfied with its performance and the quality of virtual learning. In May, several dozen parents filed suit against both the mayor and Chancellor Meisha Ross-Porter to try to force an immediate full-time return to physical classrooms.

Dan Weisberg, CEO of the reform-oriented nonprofit TNTP and a Bloomberg-era executive at the New York City Department of Education, called the unpredictable pace of reopenings “a huge black mark on Mayor de Blasio’s record.”

“One of the guiding principles should have been respect for parents and students and families,” Weisberg said. “If that’s one of the guiding principles, then you don’t repeatedly change schedules and plans the night before, or with 24 hours notice. …And that was done again and again and again, and there is still significant anger about that, as there should be. It’s a huge disrespect to parents.”

Yiatin Chu is a New York parent and co-president of the group PLACE NYC, which advocates in favor of strengthening gifted education programs and has recently co-endorsed both Adams and Yang. Much of her work focuses on fighting back efforts to scrap the increasingly controversial admissions test to the city’s specialized high schools, but she has said that many of her fellow parent advocates also look favorably on the alternatives offered by well-regarded charter networks like Success Academy. After an “eye-opening” year of closures and remote instruction, she added, the respective stances of Adams, Garcia, and Yang held great appeal.

“While they’re not saying, ‘I believe in the single test,’ or ‘I believe in charters,’ you don’t get the sense that they’ll expend their political capital or energy to take down these schools,” she said. “We’ll see where things land, but at least in the campaign season, they’re saying things I think many parents want to hear.”

But according to Joseph Vitoritti, a professor of public policy at Hunter College and an experienced chronicler of the city’s education politics, if charter backers are aiming to resurrect the Bloomberg-era disposition toward big, high-performing networks, they’ll have to do more than win a mayor’s race.

“I would think they’re encouraged by the fact that three out of the four top candidates are pro-charter — I mean, that’s a start,” Vitoriti said. “But the bottom line is that the decisions are going to be made in Albany, not City Hall….And I think that’s going to be a tough sell — tougher than ever.”

An end to the charter school cap can only come at the state level, where mayoral influence has often proved weak. The New York Senate, which was formerly held by a complex coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats, flipped fully blue in 2018, and its newly liberal majorities haven’t shown a willingness to greenlight further expansions of school choice. Even more important, Andrew Cuomo, one of the charter sector’s most steadfast friends during the de Blasio mayoralty, could be in danger of being impeached in the next few months; even if he survives, it’s an open question whether he will seek a fourth term next year.

Robin Hood’s Buery said that, regardless of who wins the Democratic nomination next Tuesday, the place of charters in New York is now too firmly entrenched for either city or state leaders to dislodge. A combination of factors — more representative leadership at the school level, successful lobbying from political allies, and the consistent support of African American and Latino voters — have created a “fundamentally different world” for charters, he observed.

“There’ll still be debates about how the sector should grow, and I don’t want to discount the challenges involved. I just think it’s a different kind of debate; we’re past the point of people asking, ‘Should there be charters?’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)