In New York City, A District-Charter Collaboration That Puts Kids First and Offers a Fresh Perspective on the Political Divide

As the politics of charter schools have gone regional, and then national, the diversity of these schools has caused a bevy of problems. As the 2020 education debates roll on, it’s clear that the country isn’t entirely sure what purpose charters serve. After all, as I’ve written before, politics is the “art” of balancing policy priorities — it’s difficult to decide how charter schools fit into big political arguments if we’re not sure what they’re for.

Why launch, fund and support charter schools? That’s what’s animating 2020 education debates. Are these publicly funded open enrollment campuses supposed to provide historically underserved families with educational options outside of their neighborhood schools? Are these mostly-not-unionized schools a tool for busting teachers unions? Are these outcomes-accountable schools, free from some education regulations, hosts for pedagogical experimentation?

These are deep, difficult questions that strike at the heart of American conceptions of public education. Do charters undermine — or supplement — the traditional aims and governance of public education?

New York City’s 20-year-old charter sector is customarily framed as a source of competition and public battles with traditional district schools. But that’s not the city’s only answer for how charters fit into public education.

Since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2013, the New York City Department of Education has experimented with a range of partnership programs aimed at expanding collaboration between district and charter schools. The city’s District-Charter Collaborative is one such effort. The DCC brings together “quads” of four schools — two traditional public schools run by the DOE and two public charter schools — for two years to share ideas about how they can improve on a common area of concern.

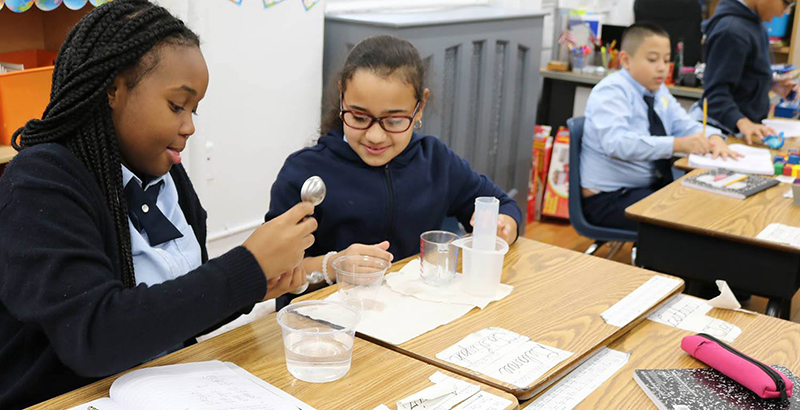

Schools in the program send teams of staff to work with a facilitator on specific ways to improve their school’s practice. They then share ideas and host “intervisitations” where teams from three of the schools visit the fourth’s campus. Afterward, the facilitator helps each campus crystallize observation lessons and develop strategies for changing their own instructional practices. Critically, the city provides small grants to each school that help administrators pay for substitutes and extra time teachers spend on intervisitations and debriefing sessions.

From 2016 to 2018, one of DCC’s quads consisted of Amber Charter School East Harlem, P.S. 401 Christopher Avenue Community School, Bedford Stuyvesant New Beginnings Charter School, and P.S. 59 William Floyd. Their quad’s chosen theme was “innovative math instruction,” says facilitator Mike Stoll, “which is pretty broad.” Over time, it evolved to focus on “facilitating problem-solving skills in some way or another.”

“All of the students, because they struggle with reading … They were struggling to deconstruct those multi-step word problems,” says P.S. 401 Assistant Principal Debra Friday. “You know, math is no longer simple computation. With all the language that’s written into math problems, [they were] performing very poorly on the New York state assessment when they were given these kinds of word problems. They just could not seem to understand the language of math.”

Each school was eager to find ways to help students understand complex word problems and apply mathematical strategies. So they showcased and swapped ideas: instructional strategies, graphic organizers, rubrics and more.

This collaborative approach echoes an old model — the original model — for charter schools. In their early years, charters were seen as a way to experiment with structures and pedagogies beyond what was possible within existing public education systems. For this model to pay off, however, successful charter experiments needed to be identified and adopted at scale in public education.

“[The DCC] helped teach me that we have so much to learn from each other,” said P.S. 59 Assistant Principal Zachary Mack.

To be sure, the DCC isn’t a perfect instantiation of that vision. It offers a two-way street, whereby charters also learn from and adopt practices in district schools. But that amendment may be a necessary improvement on the original vision, given the state of education politics in New York City. Robin Chait, an expert on district-charter collaboration at WestEd, says this could be “a potential model for other districts … if both districts and charters are seen as sharers and learners, there’s likely to be less resistance to this idea.”

The DCC organizes schools to focus on academics, but the first meetings were about building trust. Sashemani Elliott, principal at Amber East Harlem, describes the early process: “We got together so that we could work around best practices in mathematics, but our first discussions were, ‘So what have you heard about us? And let me tell you what I’ve heard about you.’”

Stoll, who now runs the DCC, says the first meeting is like “peeling the onion,” giving all participants a chance to “put some of our biases, some of our thoughts, some of our perceptions about the other sector out on the table and … talk ’em through. Almost universally, the end and conclusion of that conversation, no matter what it takes to get there is, we’re all here to work for kids, we’re all here to do the same stuff, we all love our jobs and love what we do and want to be better at it, so let’s get to work, OK? So that’s a revelation for some folks and for some schools.”

Early evidence suggests that the quad’s focus is paying off. Math proficiency rates rose steadily during the DCC process. In 2016, when Amber East Harlem joined the DCC, 41 percent of its students scored proficient on the state’s math assessment. In 2018, 64 percent did. Even more encouraging, English learners at Amber put the school in the top 5 percent of city schools for EL math performance.

The rest of the quad also saw improved math outcomes for students. At New Beginnings, math proficiency rates rose from 19 percent to 34 percent during the same period. At P.S. 401, proficiency increased from 18 percent to 30 percent. At P.S. 59, it went from 17 percent to 29 percent.

So perhaps this newfound comity could hint at a path forward in the latest iteration of the education reform wars. If more local education leaders build forums and structures that support district-charter collaboration, it would be easier to present — and support — charter schools as assets for American public education as a whole.

It’s exciting that a district-charter collaboration process that puts kids’ needs at the forefront drives better student performance. But it’s quite another matter to build on that foundation to where it improves district-charter relations.

For instance, Mack, the P.S. 59 assistant principal, says that his views on charters remain nuanced. “I don’t think DCC changed my feelings about charter schools as a whole,” but that’s just his opening. He continues, “Having worked with DCC, I think I’ve come to realize that there are a lot of — especially independent — charter schools who are really committed to doing the same work with the same students as the great public schools of New York City that function in underserved areas.”

Once they’re done clawing at one another’s throats this campaign season, charter critics and supporters ought to keep that nuance in mind. Policies that encourage district-charter collaboration (with corresponding resources and support) can help kids — but also orient charters in ways that help with the politics.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)