Williams: Some Practical — If Uncomfortable — Solutions to the Stubborn School Segregation Mapped Out by Vox

I became a Prius driver this year. The heat and air-conditioning on our 13-year-old Chevy Aveo had recently given out — another in a long string of automotive indignities visited on the old girl — and it was finally time for a replacement. And look, I’m not going to hide anything from you here — that Prius is a dream machine. I love it. I love it the way I love NPR. And avocados. And growing Thai basil in our little container garden. And reading Mo Willems’s pigeon books.

God, I’ve become a good-hearted urban liberal parent (a GULP, I guess?). We’re the latest flavor of white urban culture. We’re too busy, lame, and earnest to be hipsters, and not quite hard-charging enough to be yuppies. Praise the yoga mat and pass the Kombucha. This is my tribe. It’s 2018 in America — everyone needs one. The warmth of like-minded solidarity is so satisfying amid the instability of institutional collapse.

But as much as white parents have changed over the years, when it comes to the intersection of school and privilege, well, today’s white families are pretty recognizably the same as their own families. Just like their forebearers, they — ahem, we — are distressingly anxious about integration, selfish about their own children’s advantages, and fundamentally confused about the moral gulf between their good intentions and their actual behavior. If I had a nickel for every time that a progressive white parent here in D.C. told me some variation of “We don’t want our kid to be an experiment in that school [with a high percentage of students of color],” I’d be able to pay down my family’s student loans.

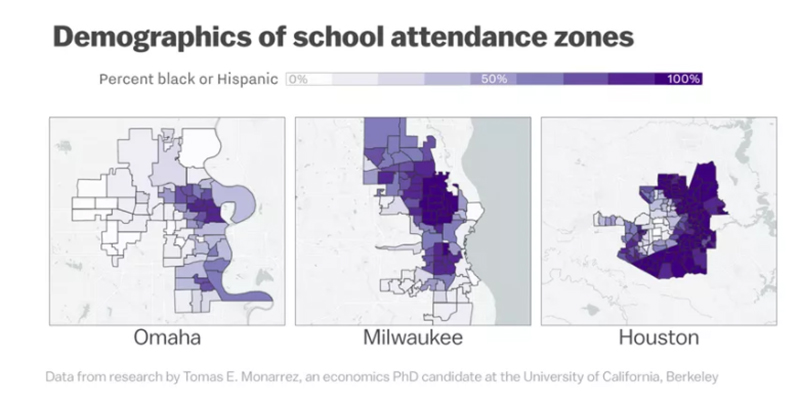

This week, Vox’s Alvin Chang published a long, searching explainer of the past and present of American school segregation. The piece echoes another that he published last summer. Both are laudably clear-eyed about the many ways American public policies have built — and protected — school segregation. Chang’s pieces are also hardheaded about the many ways that white families still avoid sending their children to integrated schools.

So: What policy options do we have? How can we change the structures of public education to reduce racial segregation?

We could try to change neighborhood schools’ enrollment boundaries, but we know that white families are likely to push back or flee the district. USC researcher Ann Owens has described the situation this way: “As long as neighborhoods are demarcated by school district boundaries limiting enrollment options, parents will take these boundaries into account when making residential choices, which may contribute to segregation between white and minority children.” Given the ongoing segregation of American real estate, any desegregation approach that assigns schools based on real estate is inherently unstable.

Right. Well, we could try to mandate busing programs to integrate a district’s schools. That tends to spark (famously “massive”) resistance from white families. So we could tempt them to integrate a school with special programming, except that they might wind up gentrifying the entire campus. Shoot, even if we manage to integrate a school, white families will often find a way to track their kids into segregated programs within it.

So … What if we made all of a district’s schools open to all students in the district? This will certainly spark some white flight, but might not spark nearly as much as a redraw of neighborhood zones. Here’s why: When we redraw enrollment areas, we just (implicitly) adjust the real estate market for folks to game all over again (i.e., they can resegregate themselves again by congregating by race in the new enrollment zones). As Chang puts it, “when the dust settles, white families insist on moving next to other white families and recreating white havens.”

But if no one gets any advantageous access to any school via their places in the housing market, they have to leave the area entirely to guarantee that their children will attend a universally privileged and segregated school.

Sure, white families would still resist the establishment of districtwide open enrollment if policymakers tried to establish a citywide schools lottery as a single, comprehensive policy all at once. But what if there were a way to slowly, steadily start new open-enrollment schools parallel to a district’s neighborhood schools? There are options here: A district could slowly convert schools into open enrollment over time on its own, or growth in public charter schools could also provide school options detached from the real estate market.

These uncomfortable facts are often lost in school desegregation thinking. Too often, integration activists propose feel-good solutions to segregated schools that run aground on the sturdy self-interest of privileged white families. If we hinge a desegregation effort on white families’ good intentions, altruism, or willingness to change their minds … we can pretty much guarantee that it won’t work.

Should we try to change white families’ minds? Absolutely. Can we change white families’ minds? Perhaps. My wife and I chose an integrated school for our kids. A handful of our friends have done the same. And yet, should we expect a mass awakening from white families on the value of integration to communities, the country, and all children (including their own)? Well … I’d like to think so, but Chang shows that American history’s not encouraging on this score.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)