Districts, Charters and ‘Public School Vouchers’: Unraveling Elizabeth Warren’s Complicated Evolution on School Choice

At a Democratic education summit held in December, Elizabeth Warren took another crack at addressing an issue she had grappled with for months: charter schools.

The Massachusetts senator was one of seven candidates who took questions on American schools at the Pittsburgh forum, which was co-sponsored by prominent unions and civil rights groups. Picking up a line of inquiry recently advanced by pro-charter activists, moderator Rehema Ellis asked what Warren would tell black and Hispanic parents who hoped to enroll their children in charters.

As school choice advocates protested outside the event, Warren pledged not to strip money from existing charter schools as president. Instead she highlighted her plan to introduce $800 billion in new federal education funding, saying that she would make “all [public schools] excellent schools.”

Observers noted that, even while striking a somewhat conciliatory note, Warren “stood her ground”; indeed, the forum was the third time she had discussed the subject in recent weeks, and nothing about the exchange suggested that she had changed her views — or that her detractors would be mollified by her performance.

Throughout the primary, her stated positions have been consonant with those of the party she hopes to lead, which has shifted fast and forcefully away from its previous support for charters. But they make for a somewhat jarring addendum to her lengthy public record of advocating for greater school choice for working families.

Over four decades, in debates over school segregation and family finance, Warren has consistently inveighed against America’s default practice of assigning children to schools based on where they live, calling it an unfair and ruinously expensive system that cuts off working families from excellent classrooms. More recently, however, the public intellectual who wrote with gusto of the need to “decouple” educational opportunity from zip code has become increasingly critical of charter schools — which, their defenders believe, do just that. At the same time, she has earned the contempt of the charter sector’s supporters, including some from her home state.

“What she’s doing is an act of political cowardice,” said Keri Rodrigues, a Massachusetts-based activist and blogger with a long history working in labor organizing and local Democratic politics. “As somebody who has organized for her, somebody who has vouched for her, the fact that she can now be so dishonest about school choice is gross.”

Reached for comment, a Warren campaign spokeswoman said that the candidate hoped to provide a high-quality education to every American student, but that public dollars should not support further charter expansion “until they are subject to the same accountability requirements as public schools.”

With both President Trump’s impeachment trial and the Iowa caucuses looming, the debate around school access has largely stayed out of the headlines. But given Warren’s status as her party’s de facto policy maven, its outcome could determine Democrats’ stance on the issue heading into the 2020s. Richard Kahlenberg, director of K-12 equity at the left-leaning Century Foundation, told The 74 that he agrees with Warren that neighborhood school assignment helps perpetuate social ills, but that he also considers her charter skepticism both fair and honestly held.

“I am uneasy with some progressives who embrace the neighborhood school,” he said. “It’s only a good deal if you have a lot of money and can buy into a strong school district. So I understand why some would be upset about a retreat on the principle of open enrollment in public schools. But I have a more charitable reading of where Warren’s coming down.”

Zip codes as ‘barbed-wire fences’

Kahlenberg sees Warren’s positions on public education as a reflection of attitudes she has held going back to the 1970s.

While enrolled as a student at Rutgers Law School in 1975, she published a journal article excoriating the Supreme Court for its ruling in Milliken v. Bradley, which limited the power of local authorities to craft desegregation plans across school districts — between, say, a predominantly black city and its surrounding white suburbs.

After a spate of decisions in the post-Brown v. Board era compelling school districts to make ever-greater efforts to break down racial divides in student enrollment, Milliken was the first to narrow the scope of the nationwide desegregation campaign. Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had argued Brown in 1954 as chief counsel for the NAACP, called the later ruling “a giant step backwards.” As the question of integration has re-entered the education discourse in recent years, Milliken has been decried as a significant roadblock to the progress of racial equity.

Warren’s article anticipated much of that criticism, predicting that the ruling’s enforcement would “lead to central-city schools which are inferior in facilities, student-teacher ratios, and other educational advantages because the funding is not commensurate with that available for suburban schools.” The insuperable barriers separating school districts, she wrote, kept disadvantaged students from enjoying the same quality of education as other children.

Kahlenberg, whose own research has heavily emphasized the importance of socioeconomic integration, said he believes that the same principle underlies her thinking today.

“When you disconnect neighborhood and school, that ironclad relationship, it offers the possibility of greater levels of economic and racial integration, and also offers the possibility of disrupting the connection between property values and your assigned school,” Kahlenberg said. “Those are both highly progressive ideas. That’s the way to understand why she advocated a system of public school vouchers or open enrollment.”

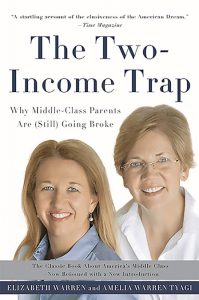

That tricky phrase — “public school vouchers” — wouldn’t appear in Warren’s writing for nearly 30 years, when then-Harvard professor Warren co-wrote the influential The Two-Income Trap with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, in 2004. Though the book dealt broadly with the economic challenges facing middle-class families at the dawn of the 21st century, its section on public education picked up some of the strands from her prescient law review article.

Lamenting the crushing pressure of housing, transportation and higher education costs on working people, Warren proposed that states and municipalities effectively do away with district assignment zones, allowing families from low-income neighborhoods to enroll their kids in better-resourced schools across town. In this way, communities could dethrone the primacy of real estate values in determining which students had access to high-quality education.

“Local governments could enact meaningful reform by enabling parents to choose from among all the public schools in a locale, with no presumptive assignment based on neighborhood,” she wrote. “Under a public school voucher program, parents, not bureaucrats, would have the power to pick schools for their children.”

Referring to the proposal as a “voucher” system has led to some confusion over the years over whether she was, in fact, advocating the privatization of public schools. But Warren — in recognition of the controversy over using public funds to subsidize private education — clarified that she was referring specifically to access to public schools. While she didn’t use the phrase, she was describing a policy commonly known as “open enrollment,” which some districts have embraced as a means of public school choice.

In a 2003 interview about the book, Warren said that she hadn’t initially intended to offer a solution to the problem of school district boundaries, but that when her book editor insisted on including one, she and Warren Tyagi reached it easily: “Decouple school assignment and zip code.”

“Parents have choices now,” she told her interviewer. “It’s just that they exercise that choice with $250,000 [home] purchases. Those who can’t make a $250,000 purchase just have a much narrower range of choices … zip codes should not act as barbed-wire fences to keep out children whose parents cannot afford homes in that district.”

These arguments are substantially similar to those of dedicated school choice advocates, who note that K-12 schools in top-performing districts are only “public” insofar as families can afford the often-exorbitant cost of housing nearby. The same activists often point to charter schools — particularly urban networks like KIPP, Success Academy and Achievement First — as life-changing alternatives that deliver top academic results to predominantly low-income and minority students.

Nine years and a Great Recession after the release of The Two-Income Trap, Warren had made the transition from obscure academic to left-wing folk hero to United States senator. And while she earned more publicity for her viral interrogations of bank executives in committee meetings, her past musings on school choice have been exhumed before. Even five years ago, the liberal news site Vox ran an admiring headline stating that Warren “wants to kill the neighborhood school.”

Shifting Democratic orthodoxy

Fifteen years ago — even five years ago — that position would have put Warren close to the center of Democratic policy orthodoxy. Since at least 1992, the party’s presidential platforms have included positive references to public school choice and broadening educational options for low-income students. In 2000, Al Gore campaigned on tripling the number of charter schools throughout the country, and President Obama’s eight years in office saw a significant expansion of the nationwide charter sector.

But the intervention of wider trends, such as a growing militancy among teachers’ unions and the appointment of charter advocate Betsy DeVos as education secretary in 2017, have led to a powerful backlash within the party. Earlier this year, congressional Democrats proposed slashing support for the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP) — a kind of seed fund to promote the growth of high-performing charter schools — by 9 percent. There are limits on how much the sector can be constrained by federal actors, since charters, like all public schools, receive the majority of their funding at the state and local levels; but in liberal states like California and New Jersey, lawmakers have pushed for outright prohibitions on new charters.

“The debate about charters has in many ways hardened into two camps: very strongly pro-charter, pro-charter expansion, and then anti-charter, anti-charter expansion,” said Scott Sargrad, vice president for K-12 education policy at the liberal Center for American Progress.

Warren has emerged as a persistent opponent of some charters, though she’s stopped short of the rhetoric adopted by their loudest detractors. Her first major foray into charter school politics came when she opposed Question 2, a 2016 ballot initiative that would have lifted a cap on charter growth in Massachusetts.

The state’s charter sector is considered by many experts to be the best in the country, and a local policy of temporarily reimbursing traditional schools when their students transfer elsewhere has smoothed over some of the fiscal challenges that go with district-charter competition. But a savvy “No on 2” campaign led by teachers unions and school committees helped drive resistance to the measure. Although voters entered the election season largely unfamiliar with the charter debate, that soon changed.

“There was definitely a shift in public opinion during Question 2 in 2016,” said Steve Koczela, a well-known local pollster who leads the MassINC Polling Group. “It started off not being a particularly partisan issue, and by the time the campaign was over, it had become much more so. Particularly among white liberals, there was a considerable drop in support for charters during the course of the 2016 ballot question campaign.”

Two months before Election Day, Warren announced that she would not support the proposal. While acknowledging that “many charter schools in Massachusetts are producing extraordinary results for our students,” she worried that Question 2 “[pitted] groups against each other” and could impose a greater burden on districts already facing financial challenges.

Voters rejected Question 2 by a margin of nearly 2 to 1, partially owing to the influence of high-profile Democrats like Warren. The senator had largely stayed quiet on the year’s other contentious political questions — including the presidential primary between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, as well as a state referendum on marijuana legalization — and local political observers found it significant that she would weigh in on charter expansion.

Activist Rodrigues, who has been unsparing in her criticism of Warren in the years since, said the senator’s stance on the issue was “so personally disappointing, especially from somebody I looked up to.”

“The fact that she’s talked about how your zip code should not determine your educational destiny … is deeply progressive,” she told The 74. “And I think that’s honestly where her heart is, because that’s what she said when no one was looking. Unfortunately, to survive in the current political context, it is now a competition to prove your undying loyalty to the teachers unions to secure their endorsement.”

Clashing with advocates

With the eyes of the nation upon her in ways that would have been unimaginable in 2003, Warren still expresses a commitment to educational access as a senator, passionately invoking government’s responsibility to guarantee all children a spot in an excellent school “regardless of state, income or zip code.”

But she didn’t fully lay her cards on the table until the October release of her voluminous plan for K-12 education, which proposed fully defunding the Charter Schools Program, along with other new restrictions that supporters of charter schools called too harsh. At the same time, she made the symbolic gesture of standing with striking teachers in Chicago, who had called for a local moratorium on further charter openings.

Opposition spread quickly among the charter movement. On certain points, particularly the zeroing out of the CSP, advocates were joined by some in the progressive policy elite. CAP’s Sargrad said that he believed “a more balanced approach” was necessary to account for the needs of parents who desire more educational options for their children.

“I do think there’s a smart approach to charter growth,” he said. “There’s an opportunity for people who are not as supportive of charter expansion to recognize that they’re an important option for families; there are a lot of families they’re serving well. And in some places, that means we should have more of them, particularly when people in the community want to start schools that meet their particular needs.”

Activists took the case directly to Warren several weeks later, disrupting her campaign event in Atlanta to protest her education plans and later forcing a backstage meeting with the candidate in which she promised to take their concerns into account.

But if that encounter opened up room for a possible detente, it was short-lived: Just a few weeks later, the National Education Association released video of an interview between Warren and its president, Lily Eskelsen García. Recorded before the Atlanta event, the discussion featured Warren speaking with pride of helping defeat Question 2 in 2016. She added that parents had a responsibility to improve their children’s schools if they were dissatisfied with them, including by volunteering and organizing for more resources.

That argument was attacked vociferously by education reformers. Asking overburdened parents to pitch in as part-time janitors and school funding activists was a demand too much, they claimed.

Sargrad took a more measured tone in assessing Warren’s intent.

“Family engagement is an important part of making the education experience a good one, but obviously it’s not a parent’s primary job to improve their child’s school. And parents are right to expect that their child is going to go to an excellent school … It’s really on policymakers to make sure that every school is an excellent school.”

Asked about the school choice debate in which Warren now finds herself a beleaguered participant, pollster Koczela said that charter skepticism had quickly become “a degree of Democratic Party orthodoxy”; still, he added, its potential impact on the presidential primary, and everything that follows, is unknowable.

“The teachers unions in particular speak with a very loud voice in Democratic Party politics, and often what they say stands a good chance of becoming the widely accepted position. That being said, there are certainly large parts of the party that feel different from that, and it’s hard to say how it’ll play out as the campaign unfolds.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)