Chicken Coops, Trampolines and Tickets to SeaWorld: What Some Parents are Buying with Education Savings Accounts

As more GOP governors turn to ESAs, some find the rules, as one former state chief put it, ‘incredibly permissive’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When former Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed a law last year that lets any family receive public funds for private school or homeschooling, he said he “trusts parents to choose what works best” for their children.

Over 46,000 Arizona students now use an education savings account, or ESA, which provides about $7,000 per child annually for a huge array of school services. But with households in greater charge of curricular choices, some purchases are raising eyebrows, among them items like kayaks and trampolines, cowboy roping lessons and tickets to entertainment venues like SeaWorld.

The apparent permissiveness is one reason Beth Lewis, a former teacher and director of Save Our Schools Arizona, opposes the program. “These are all the things that we scrape the couch cushions for to fund for our kids,” said Lewis, whose group failed to collect enough signatures to put Ducey’s expansion of the program up for a referendum.

The debate in Arizona is being closely watched by GOP governors hoping to emulate the state’s approach. With passage of a new program just last month in Iowa, there are now nine states with ESAs and at least six more considering them. As in Arizona, the Iowa program will be open to any family that wants to participate. A Florida proposal would do the same.

The juggernaut is part of a wider Republican push to win over parents disaffected by what they see as the public school system’s halting response to the pandemic and alienated by culture war clashes in the classroom. Experts say parents’ frustration over extended school closures contributed to Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s victory in 2021. And Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, widely seen as a 2024 presidential contender, has made parent choice a central focus of his administration and restricted what public school teachers can say about race and gender.

What Republicans see as a boon for family empowerment, however, many Democrats view as a Trojan horse for the dismantling of public education. In Arizona, the seemingly endless variety of options available to homeschoolers makes it difficult for state officials to regulate them — and that may be the point. The goal, school choice proponents say, is to break free of school bureaucracy and put parents in control.

“Lots of kids have different needs that public schools are not a good fit for,” said Marilyn Fitzpatrick, a Gilbert, Arizona, mom and former social studies teacher. She turned to ESAs to homeschool her oldest son Oliver after pulling him out of elementary school during the pandemic. She called remote learning with a kindergartner a “special kind of hell,” and said when he was placed in the lowest reading group, teachers told her not to worry. “It was concerning to be told, ‘It’s probably fine.’”

Others see the program as a springboard for innovation. Lura Capalongan, who is homeschooling her kindergartner Lexi, said Arizona’s ESA has allowed her to more than double what she spends on curriculum and materials — items like a small robot that teaches coding and a kit to build a simple scooter.

“I don’t feel like I’ve stretched the boundaries much,” she said. “We’ve been able to build a curriculum around her skills and her interests.”

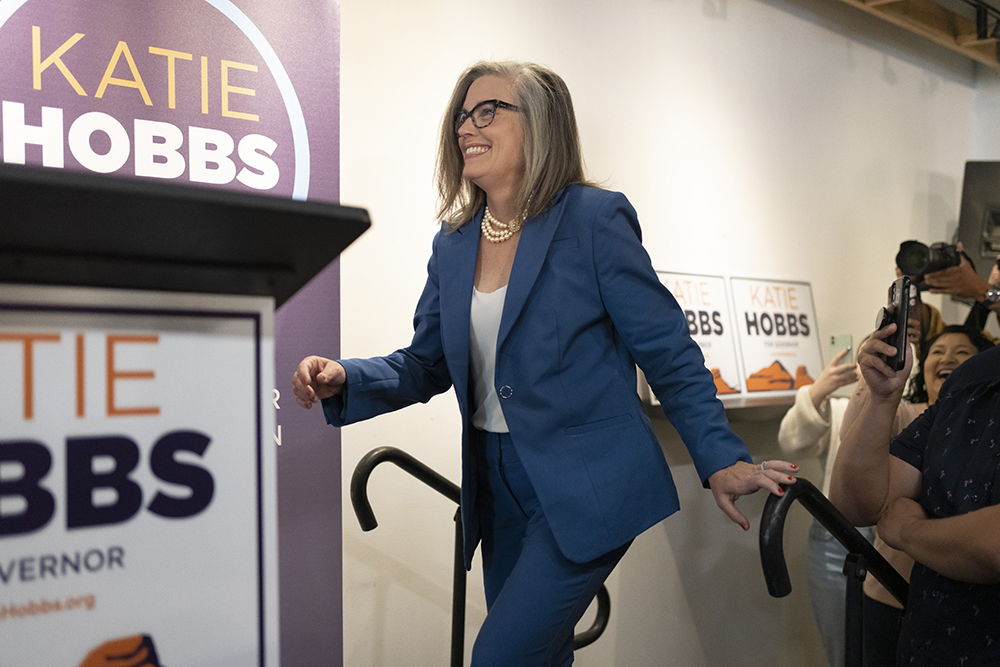

But newly elected Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs has less faith that the purchases parents are making are academically sound. Her first budget proposal includes a plan to roll back the program to a limited group of families. She told lawmakers the program “lacks accountability and will likely bankrupt this state.”

Under the law, participating families agree to provide instruction in the same content areas as public schools. In addition to more traditional lesson plans, parents report that they meet — or attempt to meet — those requirements through activities like ice skating and sword casting classes, according to posts in a Facebook group for ESA users and vendors marketing their services.

One parent in the group said she uses the Disney+ streaming service to “extend our learning” and asked if the state would approve the cost of a subscription. Others said they’ve received approvals for trampolines and horseback riding lessons.

Former state superintendent Kathy Hoffman, a Democrat who lost in November’s election to Republican Tom Horne, said she opposed the expansion because the rules are “incredibly permissive.”

“As long as an item can be tied to a curriculum — with curriculum being ill-defined and open to interpretation — that meets the definition of an allowable expense,” she said. “Striking the right balance between allowing parental choice and being good stewards of public tax dollars was a continual challenge faced by my administration.”

According to the education department’s parent handbook, some materials, like board games, puzzles and Legos, don’t require parents to submit a curriculum. But less-obvious items like dolls and stickers do. To justify buying a chicken coop for a science lesson, one parent posted a chicken-raising guide. Another suggested a workout from Fit Bottomed Girls to support the purchase of a trampoline for physical education.

Teachers for core subjects need to have at least a bachelor’s degree, but for specific classes like art, drama or dance, a two-year degree or a credential is acceptable. Vendors in the Facebook group often list what students would learn from their programs. The sword casting instructor, for example, said he would teach students “archaeology, physics, history and metallurgy.”

But Lewis, who also helped organize 2018’s “Red for Ed” protests for higher teacher pay, accuses the state of not holding families and private schools accountable. She thinks standardized testing should be required for students who receive ESAs.

“We don’t know what the kids are learning or whether they’re learning,” she said.

‘Tailored to the individual student’

Craig Hulse, executive director of Yes. Every Kid, a national organization that advocates for ESAs, thinks such criticisms are misguided. He said the public likely wouldn’t object to a school taking students on a field trip to SeaWorld or allowing ice skating to count toward a gym credit.

With an ESA, he said, it’s expected that parents’ choices would be “specifically tailored to the individual student.”

Becky Greene, a Mesa parent, has five children, ages 7 to 17, using ESAs. For physical education, they all take taekwondo. She was able to afford a $200 Time-Life series on aviation for her oldest son, a “military history buff,” and a book on the chemical reactions involved in cooking for another son interested in culinary arts.

She once wondered how a parent in the Facebook group got approved for a kayak. But as someone “used to stepping out of the box,” she doesn’t question how others educate their children.

Capalongan said she hopes to use ESA funds to help pay for the care of her daughter Lexi’s rabbit — items like a hutch, a litter box and nail clippers. Lexi joined an animal club similar to 4-H and is studying the rabbit’s anatomy and nutrition.

“It’s covering science and biology, but at a level that a kindergartner can understand,” she said.

‘Any reasonable’ expense

Prior to the former governor’s expansion of the program, it was limited to specific groups of students, including those with disabilities, in foster care or in military families.

Dave Wells, research director at the Grand Canyon Institute, a center-left think tank, said Hobbs took a “pretty important rhetorical step” by calling for a change in course. But with a Republican-controlled legislature, she might have to settle for tighter regulations to improve accountability, he said.

Now, the program’s enrollment has nearly quadrupled and the state is working to speed up turnaround time for approvals and reimbursement.

“I walked into a backlog of 171, 575 orders,” Christine Sawhill Accurso, the program’s new executive director, wrote in a January email to participants. “We are making our way through that backlog as quickly as possible while still receiving thousands of new requests each day.”

Accurso, a former ESA parent, confirmed that the state has approved chicken coops, ice skating and cowboy roping lessons among a broad variety of ESA purchases. She has updated the allowable list to more closely match state law, but has also written in memos to ESA families that the department would approve “any reasonable education-related expense.”

School choice advocates in other states are watching Arizona as officials try to define what’s reasonable.

Texas Republican Sen. Mayes Middleton has introduced a $10,000-per-student ESA bill that would allow “every type of education” to qualify. Under his plan, the state comptroller would run the program instead of the education agency to avoid debates over curriculum.

“The money is going to be spent,” he told The 74. “Do you want only the government to decide [what to teach], or do you want parents to decide?”

In New Hampshire, by contrast, the state applies some “Yankee frugality” to its program and rejects requests for purchases that could be used by multiple family members, like a kayak or trampoline, said Kate Baker Demers, executive director of the Children’s Scholarship Fund.

“Right out of the gate, we said, ‘This is narrower than you think,’” she said. “We want to run it in a way that everyone can be supportive of it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)