In Alaska, a School of the Future 50 Years in the Making

Aldeman: Mat Su Central's hybrid flexibility, portability for families, student built-in monitoring & academic support make it an approach to consider

Last spring, I had the chance to visit a school unlike any I had ever seen before.

Mat-Su Central in Wasilla, Alaska, is hard to label. It might accurately be called a hybrid homeschool, but that newfangled term belies its much-older origins. The school’s unique history helped shape it into what could be a model for the rest of the country, and it has lessons for any state or district leader looking to deliver personalized, high-quality public education.

Mat-Su Central is a public school with about 2,200 students in grades K-12. It takes all students, and its workers are employees of the Matanuska-Susitna Borough School District. Its district is the second-largest in the state of Alaska, serving nearly 20,000 students spread out across a geographic area roughly the size of West Virginia.

To reach all families, especially in the harsh winter months, in 1972 the Mat-Su district opened a correspondence school, which allowed students who weren’t physically present to complete coursework in their own homes on their own time. Its licensed teachers functioned more like advisers. They worked with families to craft an educational plan, but parents had to take some responsibility for teaching and even grading their child’s work, with the school providing ultimate oversight to make sure kids remained on track.

Over time, Mat-Su Central’s leaders noticed that too many students weren’t graduating. After engaging a core group of families, they diagnosed the problem as a lack of connection among students, teachers and peers. So, a little more than a decade ago, the school added on-site classes to shift away from pure distance learning into the hybrid model it operates today.

Every student has an individual learning plan that teachers, parents and students build together. They incorporate each student’s strengths and weaknesses and take into account classes the students need in order to graduate — such as reading, math, science and history, as well as any remedial work — and subjects they want to pursue, including art, music, welding and gymnastics.

Some families opt for fully virtual classes, akin to private homeschooling but with the guidance and oversight of Mat-Su teachers. Other students want more in-person interaction, and they can take up to two classes at their local public school, enroll in college courses, attend classes on site or participate in local community programs. This flexibility affords families choices about what classes their kids want to take and what format they want to take them in.

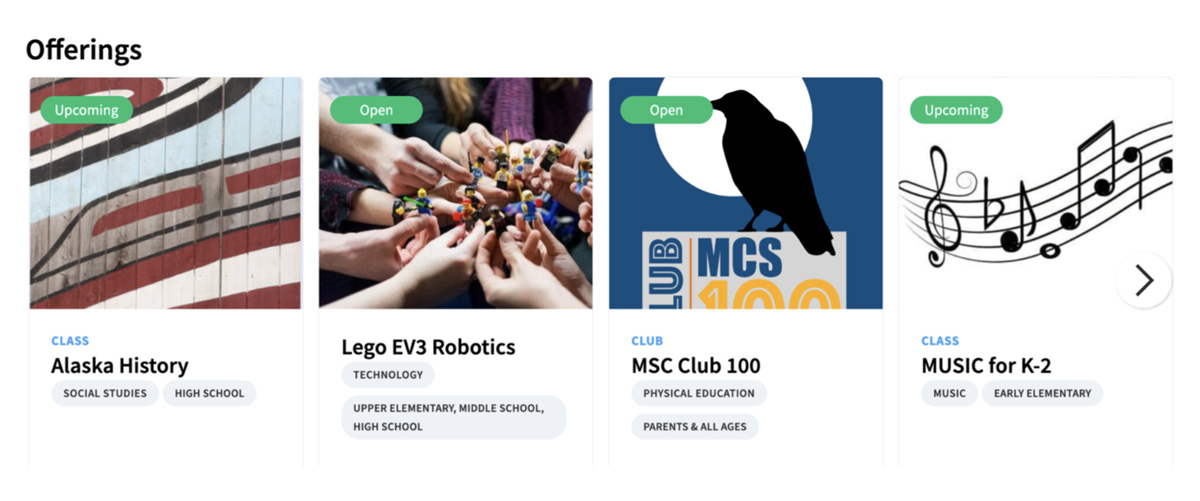

Parents can talk through those choices with their advisers, and the school has an online roster that lets users sort potential offerings by grade, subject and method (online, hands-on or paper and pencil), and how the material is graded (by school staff, by parents or through an external provider). The site features staff notes listing the advantages and disadvantages of different curricula and whether those are available to rent from the school.

Mat-Su Central doesn’t have traditional classrooms, but it has dedicated art, music and technology rooms, plus a student-run coffee shop and flexible spaces for a variety of programs. On any given day, those rooms might be used by teachers for traditional subjects like history or Spanish, but they may also be used for walk-in math labs or guitar or ukulele lessons. A series of informational “Flapjack Friday” events touch on topics such as building household budgets or traveling to Europe.

Families have access to educational options through allotments of $2,600 to $3,000 per student, depending on grade level. It’s not a voucher or cash payment; the school retains control of the money and is responsible for paying and vetting vendors. Each child’s learning plan outlines how the allotment will be used, including for curriculum, community programs or other educational services. Students can also put the money toward a computer and monthly internet service.

Over time, the school has curated a list of 300 community business partners who provide instruction and learning opportunities. (Each vendor must have a business license and pass the school’s quality review, as well as background checks for anyone working with students.) My favorite: This being Alaska, students have the option to use a portion of their allotment to earn their pilot’s license, in lieu of driver ed programs at many schools.

Even with the allotments, Mat-Su Central spends only $7,975 per pupil, less than half of the district’s $16,545 average. One reason is that the school doesn’t deploy teachers in normal classroom roles. Instead, it has 25 advisory teachers. Each serves as the teacher of record for an average of about 100 students, and some also provide tutoring or work with children with disabilities. They help craft and monitor students’ learning plans and guide families throughout the year.

The school has full-time art and music teachers on site, a nurse and two counselors who are available for in-person or telehealth visits. Advisory teachers can also design supplemental offerings for students to choose from.

As the school’s core mission is serving families, staff members have been known to drive to students’ homes for parent meetings, met up at a coffee shop to work on a child’s learning plan or connected at Target to drop off textbooks.

Still, Mat-Su Central puts a lot of responsibility on parents to monitor their child’s progress and even step in as instructor or evaluator. It doesn’t serve the full-day custodial role of a traditional school or provide transportation.

It’s also hard for outsiders to know how well students at Mat-Su Central are performing. The state has flagged the school as needing “additional targeted support” because of low achievement among English learners. Principal Stacey McIntosh attributes that to the very high percentage of families who opt out of state exams. She also notes that each individualized learning plan must include a standardized test to measure student proficiency, as well as a specific plan spelling out how any child not already proficient is going to get there.

One testament in Mat-Su Central’s favor is that families continue to flock to it. Enrollment in Mat-Su Central has roughly quadrupled over the last 20 years, far outpacing student population increases in the district and the state. McIntosh attributes that demand to concerns about bullying or students experiencing anxiety at more traditional schools, and she noted that pandemic-era closures led to a particular surge in interest. Going forward, the district is about to break ground on a new building for the school to continue expanding its on-site offerings of clubs, classes and workshops.

After seeing Mat-Su Central in person, I left believing that every state needs a hybrid homeschool like it. This could take the form of “statewide districts” as Robin Lake and Kelly Young outlined in a recent report for the Center on Reinventing Public Education. Or, states could grant individual school districts or charter schools the authority to serve families from broad geographic areas.

Mat-Su Central’s hybrid model may not be for everyone, but it provides an option for children who aren’t well served by traditional public school districts. The combination of flexibility and portability for families, along with built-in monitoring and support from the teacher advisers, makes it an approach for other states to consider.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)