There Are Three Times as Many Latino Students as Teachers in America. Two New Reports Show Why That’s Bad for Both

Latino teachers are eager to serve as role models and cultural stewards, but they feel their extra work as interpreters for Spanish-speaking families is undervalued, according to a new report from the Education Trust. Many see the additional responsibilities of community outreach as a second job they are expected to perform.

The report comprises responses from 90 Latino teachers in five states (New Jersey, North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and California) about the complexities of teaching Latino students, as well as their relationships with white colleagues and administrators, and their hopes for professional advancement.

Two themes emerged: the importance of Latino instructors in classrooms where large numbers of students are Latino themselves, and the expectation — often voiced by supervisors — that they act as Spanish-language resources for schools and families.

Many hope to provide an example for students of a first- or second-generation American who has attained advanced degrees and professional success. While stressing the diversity of the Latino experience in America — some respondents were born in the U.S., while others emigrated from Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador — they said they feel a special kinship with students who share their background, particularly at a time of heightened anxiety around deportation and family separation.

Beyond their instructional duties, the teachers stressed their role as “cultural guardians,” introducing their students to Latino history through culturally relevant texts and the selective use of Spanish in class. This is especially tricky, they added, given the requirements of academic standards like the Common Core.

But the added work of acting as a bridge to Latino parents, many of whom struggle to access educational services for their kids without an advocate, can be overwhelming, they said. Schools with only one or two Spanish-speaking staff members sometimes rely on them to mediate between parents and teachers, or even to translate districtwide curricular materials.

“I think of even student-teacher conferences [that leave] parents and families feeling unwelcome … and no one’s going to [help] the families that they can’t communicate with,” one teacher said. “Suddenly, I’m in charge of every Hispanic student that we have in sixth grade, which is the majority of all of our students, and it’s an extra job on top of my job to communicate with all those families.”

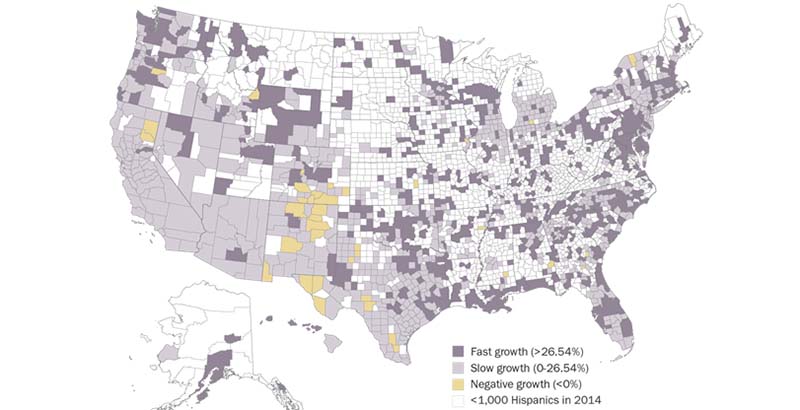

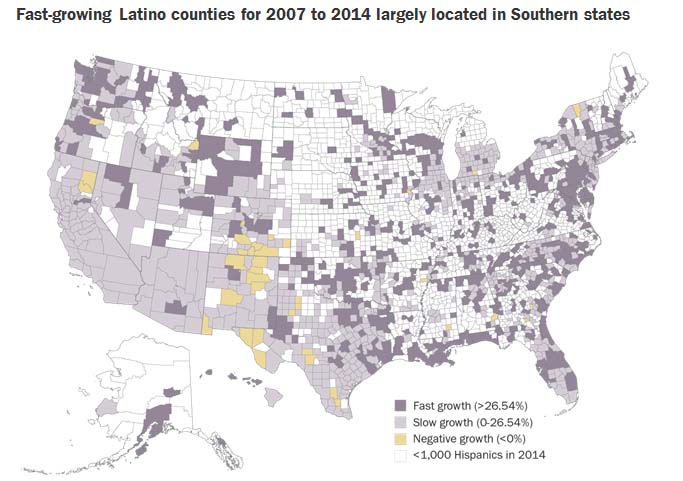

The pressure of acting as part-time interpreters and school ambassadors is widely shared, in part because there are so few Latino teachers. While roughly one-quarter of American K-12 students are Latino, less than 10 percent of teachers are. Those gaps are most acute in border-adjacent states like Texas and California — but the counties experiencing the fastest Latino population growth are mostly found in the Pacific Northwest, the mid-Atlantic states, and the South.

Research has shown that early exposure to a teacher from the same racial or ethnic group can lower dropout rates and boost educational attainment among minority students. Hundreds of districts are searching for Latino teachers — especially men — to keep up with the surge in Latino students. (The Education Trust’s respondents were almost 90 percent female, a lopsided composition that points to the difficulty of attracting young Latino men to the profession.)

Helpfully, the Center for American Progress has released a research brief offering three recommendations to widen the talent pipeline.

First, it advises Congress to pass a clean Dream Act protecting immigrants currently in danger of losing their protections under the Obama administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Of nearly 700,000 young people covered under DACA, about 20,000 work as teachers. Many are college-educated and bilingual; given the shortage of qualified replacements, deporting so many would be a significant step backward.

Equally important, the authors argue, are financial incentives to help students pursue teaching degrees and earn a license. Latinos currently lag behind all other ethnic groups in college graduation, and the Trump administration’s proposed budget cuts to grant aid and federal loan programs could push postsecondary education even further out of reach for promising low-income students. According to new research from the Brookings Institution, rates of both student borrowing and default are nearly twice as high for Latino students as for whites; making college more affordable could guide many to careers in teaching.

Finally, the brief points to the success of alternative teacher certification programs like Teach for America and the National Center for Teacher Residencies, as well as local grow-your-own programs in Oregon and Washington. All have fostered strong pools of minority talent, but the grow-your-own model — which typically focuses on credentialing bilingual candidates already working in classrooms, like teaching assistants and paraprofessionals — could be particularly attractive to localities.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)