Despite May’s Slight Economic Rebound, Working Students Continue to Face Shattering Unemployment Numbers

Updated June 6 | This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go deeper: See our full series.

Working students are facing unrelenting record-high unemployment, even as the economy showed some recovery last month, the Labor Department said Friday. Those without at least a high school degree continue to suffer most from the worst joblessness since the Great Depression, and state education employees saw further job losses.

“While the overall numbers are encouraging, they also include critical warnings about the crisis facing state and local governments, including public education,” Rep. Bobby Scott, chairman of the Committee on Education and Labor, said in a statement Friday. “Local governments shed 310,000 education jobs over the last month. At a time when schools are facing higher costs and difficult challenges, we are at risk of experiencing a wave of teacher layoffs in school districts across the country.”

The U.S. shattered economists’ expectations by adding 2.5 million jobs in May, dropping the unemployment rate to 13.3 percent from 14.7 percent in April as Americans started to go back to work two months after the coronavirus outbreak shuttered much of the economy. While much of the movement back to the workplace is attributed to the return of employees temporarily laid off due to stay-at-home orders, the number of people who lost their jobs permanently continued to rise in May, increasing by 295,000 to 2.3 million, according to the Department.

Even as overall unemployment retreated, the share of working students out of jobs continued to hover around 30 percent, yielding little relief to students who may be in the workforce to support their families, cover costs of education or otherwise. Around 70 percent of all college students and 25 percent of high school students work.

Working while in school can be a double-edged sword. Students who work can have lower grades or may be more prone to dropping out, but they also tend to earn higher wages after graduation, according to research out of Rutgers University. That, coupled with recent school shutdowns that threaten students’ ability to graduate, could lay the groundwork for an entire generation of young people to earn lower pay than those before them — for years into their careers.

“Undergraduates who both work during college and complete a degree gain the most in terms of a post-college earnings advantage,” write Rutgers researchers Daniel Douglas and Paul Attewell. “While that is the optimal outcome, college students who accumulate credits short of a degree while establishing a work history also benefit from higher pay after entering the labor market.”

Despite last month’s easing, the unemployment situation is still worse than it was at the bottom of the Great Recession. Government employment also fell last month, the Labor Department said, particularly in state education, which lost 63,000 more jobs in May while schools remain closed and localities grapple with stabilizing their economies. The month prior, declines in education employment already outsized those of the entire Great Recession. Meanwhile, employment in private education rose by 33,000 over the month.

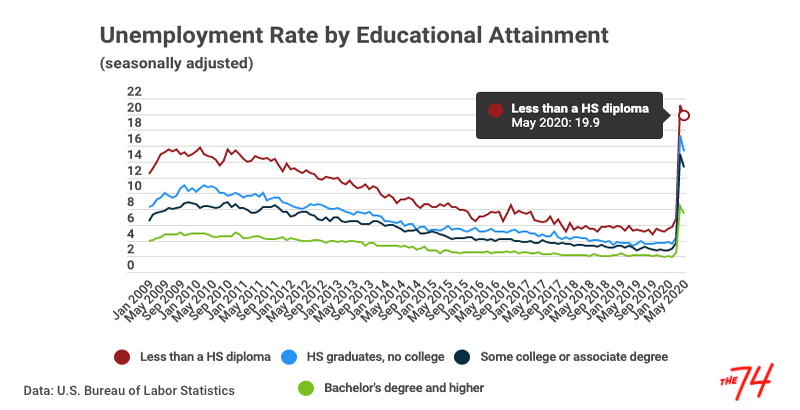

Friday’s jobs report also followed recession trends that show that workers with the lowest levels of education get hit the hardest when the economy takes a nosedive, although even those with advanced degrees are not immune to layoffs. Around 20 percent of Americans without a high school diploma were without a job in May, compared with about 6 percent just three months ago, before the coronavirus outbreak. The unemployment rate for those with a bachelor’s degree or more, however, rose to 7.4 percent from 1.9 percent over the same period.

For those with advanced degrees like master’s degrees or doctorates, in particular, jobs are still tougher to come by than they were before the pandemic. And, unlike the last recession, going back to school to ride out the storm is a more challenging prospect amid school closures.

Still, when broken down by race, a higher level of education protected Asian workers from job losses of epic proportions. After achieving record low unemployment last June, Asian Americans fell out of work at staggering rates as COVID-19 warped public perception of Asians and their businesses. In the second week of April, New York state saw a 10,210 percent increase in unemployment filings among Asians from the year prior.

In May, the unemployment rate for Asians without a high school diploma skyrocketed to 33.8 percent, more than 10 percentage points higher than for other racial groups. The Asian jobless rate, however, fell to be below or on par with other groups among those with bachelor’s degrees or higher.

The FBI in March forecasted a rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans, noting in a report that the warning was made “based on the assumption that a portion of the U.S. public will associate COVID-19 with China and Asian American populations.”

Clarification: The unemployment rate is calculated based on the percentage of Americans who are without work and actively searching. The Labor Department noted that those categorized as “temporarily unemployed” during the shutdown were instead classified as employed but “absent” from work for “other reasons.” Department noted that the overall unemployment rate would have been about 3 percentage points higher than reported,” placing the May unemployment rate at 16.3 percent.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)