Record-Breaking Coronavirus Job Losses Devastate the Least Educated — and Have Already Displaced Highest Degree Holders Worse Than the Great Recession

An ominous reality was made clear in the Department of Labor’s new employment figures Friday morning: Unprecedented job losses hit the least educated the hardest, but even those with higher degrees weren’t protected from the downturn.

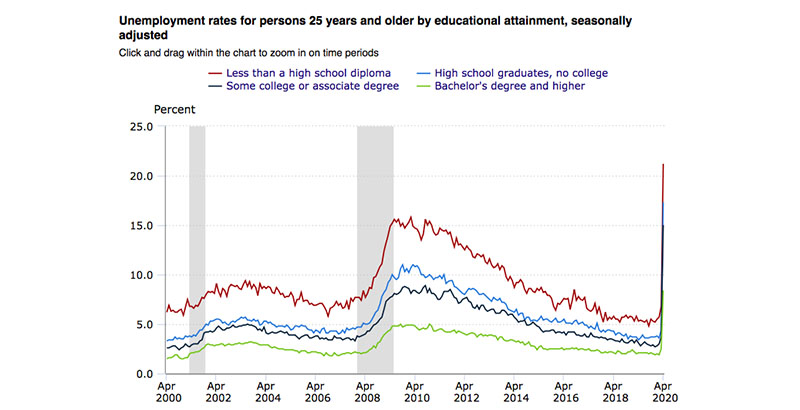

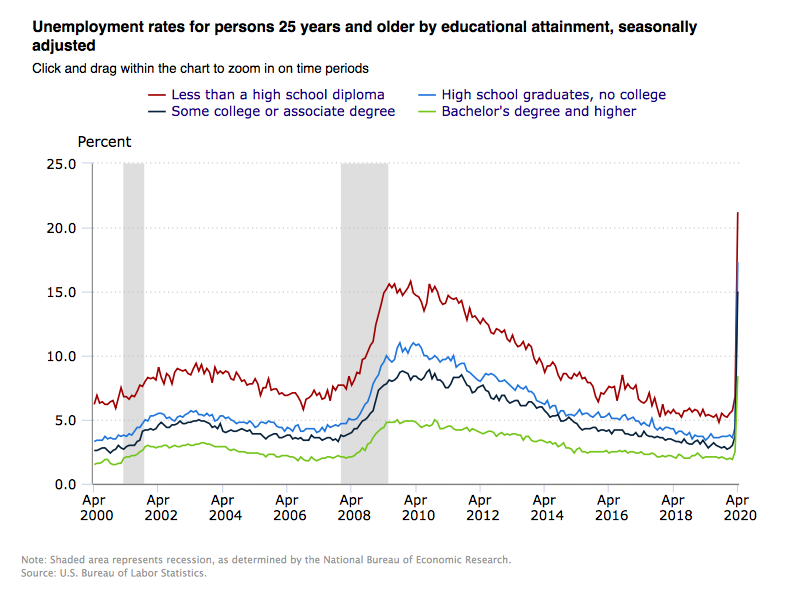

Just months ago, the United States was celebrating “the longest economic recovery in history,” marked by record-low joblessness among those without a high school diploma or a bachelor’s degree. Unemployment had dipped below the rates seen in the internet-fueled boom of the 1990s, and even low-wage workers were beginning to collect bigger paychecks after a decade of slow growth.

Then came COVID-19, erasing a decade of progress within weeks. When the Class of 2020 walks across the stage in a month’s time, they will be graduating into the most volatile labor market in memory — and the damage is being absorbed even by highly educated professionals.

After weeks of soaring unemployment applications at the state level, the report was the first to show a full month’s look at the extent of the pandemic’s wreckage: Total unemployment soared from 4.4 percent in March to 14.7 percent in April as the dawning recession culled 20.5 million jobs. Even the worst months of the Great Recession, which unfolded over more than a year, never approached such depths.

Look closer, though, and the news becomes even more alarming. While the financial crisis of 2008 put millions out of work for years at a time, the damage was felt less acutely by those with post-secondary education. Unemployment for those with bachelor’s degrees or more, for instance, never climbed above 5 percent during the Great Recession; those who completed some amount of college, or who held an associate’s degree, peaked at 8.9 percent unemployment.

Just three months into the coronavirus outbreak, jobless numbers for those workers are looking far worse. Americans with limited college were coasting at 3.7 percent unemployment in March; today, 15 percent of them are unemployed. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher have hit 8.4 percent unemployment. Men and women with advanced credentials, such as master’s degrees or doctorates — a rarefied and highly coveted sliver of the workforce — are now experiencing 6.2 percent unemployment, a rate significantly higher than those with only a bachelor’s degree during the last recession.

And yet the highly educated are still comparatively fortunate. One-sixth of all employees who have completed only high school are now out of work, along with one-fifth of those lacking a diploma. Such workers tend to enjoy less job security even in much stronger economic times, and they are disproportionately concentrated in service-oriented industries like travel, hospitality and retail, which have been particularly hampered by the social distancing measures made necessary by COVID-19.

Education professor Paul Harrington, director of the Center of Labor Markets and Policy at Drexel University, said that the trends in joblessness were “closely associated” with levels of educational attainment.

“College graduates were best insulated from the worst effects of these massive job losses,” Harrington said. “Employment fell by a massive 6.65 million over the month among those with a college degree, but relative to those with fewer years of schooling, we see that the pace of college graduate job losses were only about half that of their high school graduate counterparts.”

By contrast, Harrington noted that industries predominantly employing college graduates — such as finance, government, and professional and technical services — were cushioned somewhat from the outbreak’s worst effects. Careers in those fields rely more sparingly on face-to-face interaction and are consequently more conducive to remote work.

The ugly state of the economy raises the question of what will happen to the legions of young people who recently finished high school and college and are about to start looking for work. For many, the pandemic has already cost them summer jobs or internships that would have provided their first taste of working life.

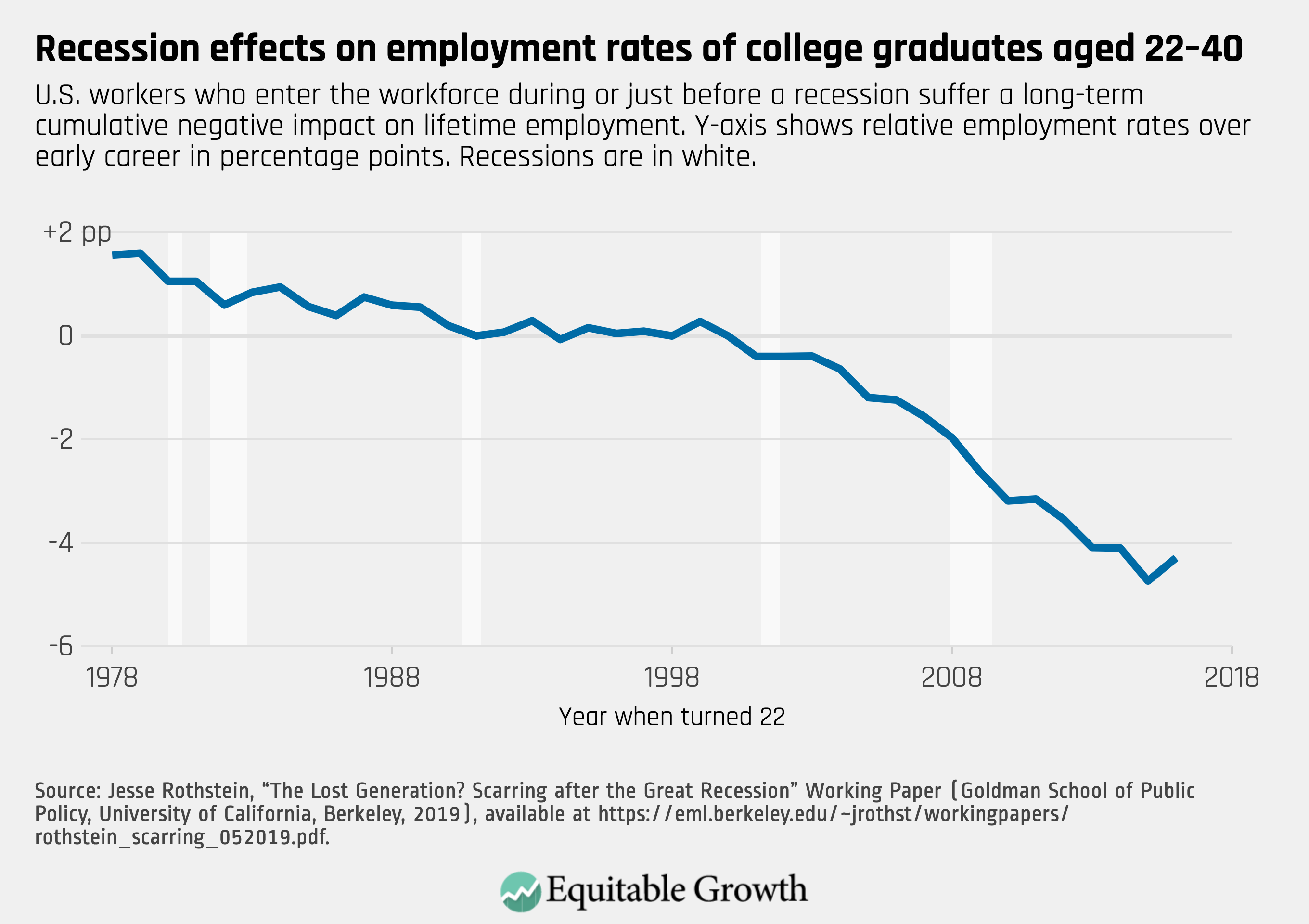

Mountains of economic research suggest that students graduating in the midst of a recession experience will receive lower wages long into their careers. One analysis indicates that the earnings of recent graduates are initially 9 percent lower than they would have been without an economic downturn — a prolonged effect referred to as “scarring,” and one that doesn’t recede for years. Nicole Smith, chief economist of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, called the abrupt contraction “nothing short of devastating.”

“For the graduating class of 2020, entering the job market now is nothing short of disastrous,” Smith said. “Jobs postings have been down by over 30 percent compared to the same month in the previous year. Furthermore, those lucky enough to get a job will invariably experience ‘scarring’ as they play catch-up to earn what they should have in a better economy.”

Just a year ago, the Class of 2019 was heading into a much sunnier economic climate. At the time, analysts from the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute noted that low-wage workers had seen increasing wage gains over the previous few years, making additional growth likely as the labor marketed tightened further. Soon-to-be graduates can’t count on the same trends prevailing now; in a blog post Friday, EPI senior economist Elise Gould called the Labor Department’s release “a waking nightmare.”

And with the economic downturn threatening to pinch state and local budgets, financial experts have warned that school districts themselves may have to resort to layoffs in the coming months. Hundreds of thousands of teachers lost their jobs during the Great Recession, and overall spending on education declined in dozens of states.

It is difficult to tell whether a similar phenomenon is taking shape now. The Labor Department’s statistics show that unemployment in the “education, training, and library occupations” skyrocketed to 14 percent in April from 3.1 percent in March.

In an email, school finance expert Marguerite Roza cautioned against attributing those job losses directly to school districts, which reportedly haven’t yet slashed much spending. But the massive influx of new job seekers might change the outlook for promised teacher salary increases.

“A year ago, teacher turnover was high (and there were shortages), but now, with so many people out of work, the labor market is completely different,” Roza said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)