Analysis: What Lasting Academic (and Economic) Effects Could Coronavirus Shutdowns Have on This Generation of Students? Some Alarming Data Points From Research on Previous Disasters

Though we can guess at the academic effects of the COVID-19 school shutdowns, the full impact of the lost learning time won’t be known for decades. Research on previous school closures may be helpful to guide our response. Those studies find negative effects on two levels.

One is that school closures can disrupt educational trajectories if students use the opportunity to make different life decisions than they otherwise would have. Another: Lost learning time has the largest effects on the youngest students.

School closures affect students inequitably on both levels. The American education system has never been a paragon of equality, but the COVID closures are likely to make those problems much worse.

Based on the research on school closures in other circumstances, we will need to respond to several distinct challenges. First, there’s the task of trying to keep as many students as possible progressing through the education pipeline. This will mostly affect older students, in high school or college, who are at risk of dropping out now in order to take advantage of immediate job opportunities.

This has happened before here in the United States. In 1916, schools in many places closed for several weeks in the midst of a polio outbreak. When researchers looked back, they found that younger students eventually returned to school, while working-age students who lived in communities with more cases of polio eventually completed fewer years of schooling.

These types of disruptions seem to be getting the most attention right now. After all, it’s easiest to see the effects of the coronavirus on the educators and students whose lives are clearly upended. Teachers are adjusting to a new reality of remote learning, while seniors who were completing graduation requirements, planning for commencement ceremonies and heading toward college or careers have been thrown into turmoil. For college students specifically, past recessions suggest that seniors who were on track to graduate may suffer worse economic outcomes that will follow them through their early working years.

Studies also find large and long-lasting effects on the youngest students.

Researchers have attempted to quantify the loss of learning from school closures in a number of contexts. Natural disasters provide one useful parallel. For example, test scores fell in Thailand the year after severe flooding in 2011 forced schools in some provinces to close for up to a month. The losses were the most pronounced for younger students.

The same pattern is likely here. When NWEA looked at historical testing data, it projected that younger students were most at risk from lost learning time. Because younger students typically learn more during a normal school year, they have more to lose by not being in school.

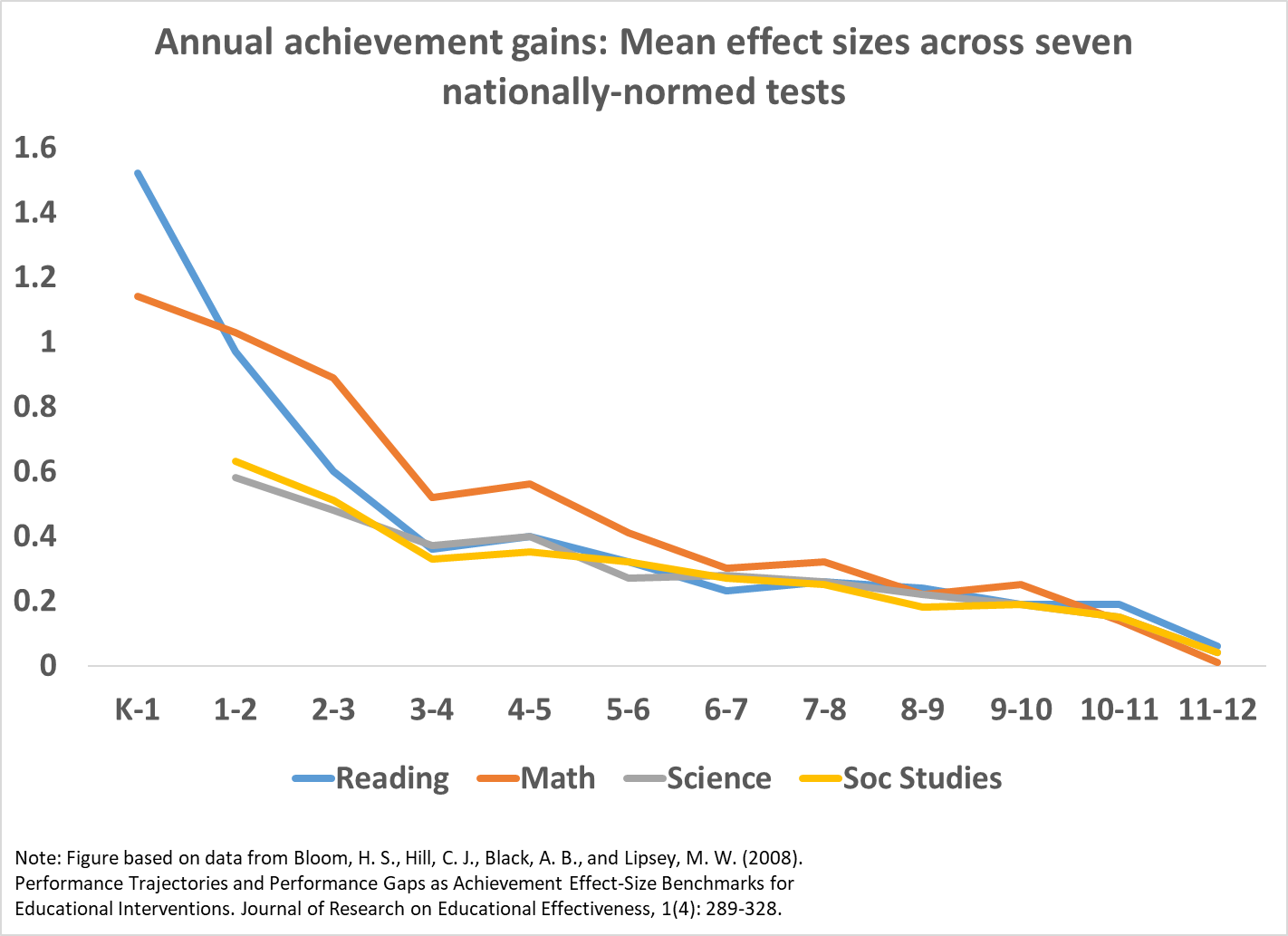

The graph below helps show this visually. It’s adapted from a 2008 review by research group MDRC. Each line in the graph represents one of four academic subjects — reading, math, science and social studies. Although the learning gains vary by subject, they all show the same pattern: Younger students learn much, much more over the course of a year than older students do.

We see similar age-related patterns in research on the effects of snow days. When researchers Dave Marcotte and Steven Hemelt looked at the effects of snow days on Maryland children, they found larger learning losses for third-graders than for fifth- or eighth-graders.

It’s possible that these studies are too pessimistic for the current moment. After all, here in the U.S. during COVID-19, schools are at least attempting to offer remote learning opportunities. But those efforts seem spotty at best, and younger students are the hardest to serve in a remote context.

Argentina provides an alarming example of what might happen if those efforts fail. Starting in the early 1980s, Argentinian provinces suffered through a wave of teacher strikes that caused students to miss an average of 88 days of learning. The strikes caused a decline in high school and college completion rates, as well as lower employment rates and earnings. The authors of a 2017 research study found that 30- to 40-year-olds who lived through the strikes earned 3 percent less than they otherwise would have. This amounted to an annual loss of more than $700 million to the Argentine economy.

The study also found that younger students were slightly more affected by the shutdowns than older students. What’s more, the effects extended beyond a single generation. The children of the students affected by the lost learning time also had lower educational outcomes, implying that a large learning loss may pass down from generation to generation.

In the present moment, even a return to “normal” may seem daunting for our education systems. With COVID-19 case counts and deaths still rising, and millions of Americans newly unemployed, the immediate economic consequences of the coronavirus are real and alarming enough.

But this is not the time for complacency. History suggests that merely going back to normal would be a disaster for our youngest, most vulnerable children.

Chad Aldeman is a senior associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)