Within NYC’s Highly Segregated School System, a Group of Low-Income Students Sacrifice Their Summers, Weekends for a Chance at College Success

Every year, the SEO Scholars program asks 14-year-old, low-income freshmen in New York City for a staggering commitment: to spend one month of their summers, three out of their four Saturdays every month, and one school night each week in a classroom.

By the time they graduate high school, they’ll have learned 2.5 years’ worth of English and 1.5 years of math — entirely outside of the city’s public schools. Not to leverage an advantage, but to have a viable chance at college and career success.

“SEO [Scholars] is not an extra level. SEO has always been a bridge,” senior Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye said of the nonprofit program, whose earliest iterations date back to the 1970s. Since 2006, it’s seen more than 95 percent of its students matriculate to college. “It takes the kids who are often forgotten by the school system and makes up for the education that our school system never gave us.”

New York City is the largest and one of the most segregated school districts in the country, a reality that recently fueled almost-weekly student protests and widespread calls for reform. School resources can hinge on zip codes; a wealthy Upper West Side school saw $2.1 million in PTA funding last year, for example, compared with some schools in higher poverty areas reporting less than $5. And while there are selective admissions high schools in the city that send students to the country’s top universities, fewer than half of students systemwide are currently proficient in math and English, mirroring national trends.

Sixty-two percent of 2018 graduates were college bound — a city record — but only 51 percent met the local CUNY system’s English and math standards.

Recognizing that there are “too many students who are losing out,” SEO Scholars has transformed over time into a robust, eight-year program resolute on getting students both to and through college, the program’s leaders say. In New York City, about 275 freshmen from a pool of more than 1,000 applicants are accepted each year — 80 percent of whom are black and Latino. Eighty-five percent would be first-generation college students.

“Every day [students] are being undereducated, and we can’t wait,” said Millie Hau, SEO Scholars’ vice president for high school programming.

SEO becomes these scholars’ “advocate and ally” through high school, providing free services such as “rigorous” academic curriculum, SAT prep and guidance on college and financial aid applications, thanks to about $11 million annually from private donors and foundations. It then sticks with these scholars through college, acting as a personal adviser and helping them hone career skills, such as networking, résumé building and interviewing.

There are about 1,000 high schoolers and 800 college students in the NYC program.

Hau noted that the nonprofit doesn’t place blame on public schools for being unable to provide all of those supports. “We recognize that schools, they have a lot of different needs in their building, and sometimes they are unable to serve all of them in the way that they want,” she said.

When freshmen join SEO Scholars, achievement gaps are recognized immediately: Students score an average of 60 percent on an in-house diagnostic test based on middle school math and elementary and middle school English. Flash-forward, and of the 86 percent who stay with the program through high school, 100 percent are accepted to four-year universities. And typically, 90 percent get a diploma within six years, eclipsing the roughly 60 percent national average for all students and light years beyond the 11 percent college success rate for low-income, mostly first-generation students.

For all the students interviewed, the program’s existence is bittersweet — a life-changing opportunity born from systemic failures in the education system. It’s opened their eyes, they said, to what they deserve and what they’re capable of achieving.

“We experience the inequities that we’ve experienced in our public education, and we kind of become complacent to them,” said Alexander Rodriguez, a senior. “We don’t really say, ‘Oh, this is a problem,’ because this is how it’s always been. But SEO has really just called it out for what it is. ‘No, this is an inequity, this is injustice, and that’s why we’re here.'”

Kendall Acheampong, 16, Brooklyn College Academy

Kendall Acheampong makes the 35-minute commute from his school near Prospect Park to SEO in lower Manhattan on the B35 bus and 2 train on Wednesday nights. There, especially in math class, he is in his element.

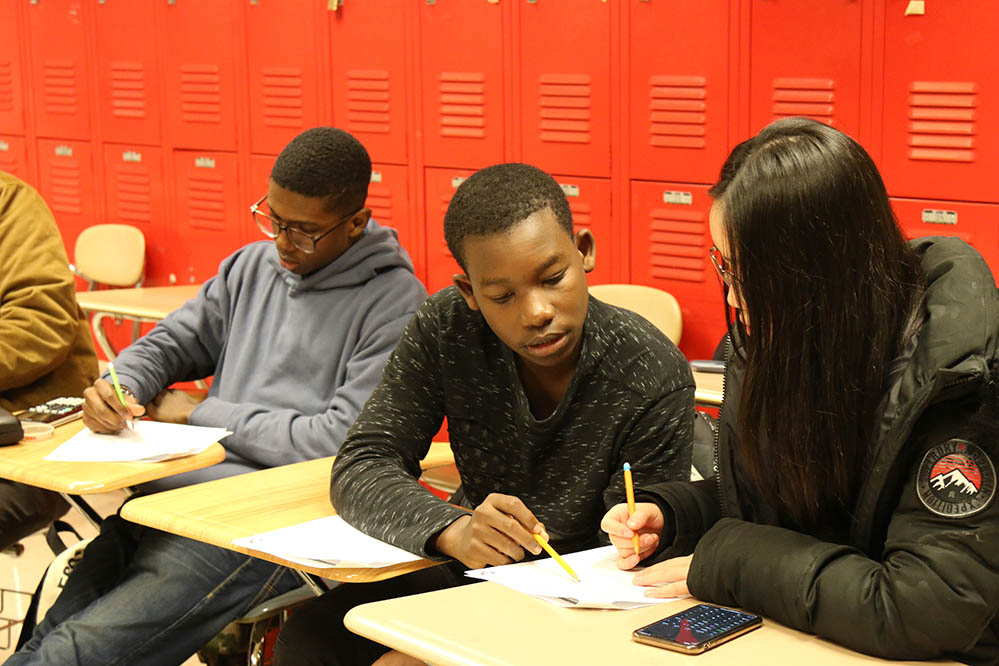

During a class in December, the 16-year-old breezed through his algebra worksheet, migrating to other peers’ desks and walking them through the material — to the point of delaying discussion of the answers. “Kendall, we’re starting,” the teacher pressed.

It hasn’t always been like that. “When I came into SEO, I wouldn’t say I was bad at math, but I wasn’t as good as I am now,” Acheampong said. “Now, I just look at math and I’m like, ‘This is kind of easy.’ It clicks with me.”

SEO Scholar’s Saturday classes focus on math, critical reading and writing, and grammar, with weekday instruction reviewing and reinforcing those concepts. For juniors like Acheampong, math lessons also act as SAT prep. Each week comes with an average of two to three hours of homework assignments across subjects.

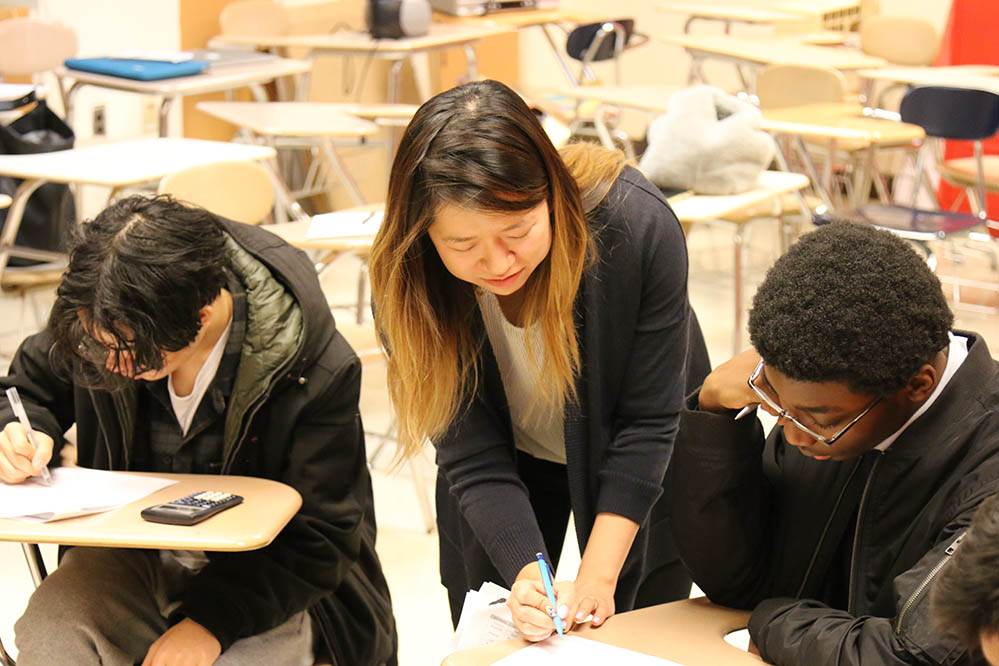

A large part of his improvement in math, Acheampong says, is the individualized attention. “There’s less kids [in SEO classes], so the teacher has time to come to me if I’m needing help or come to me if I’m struggling,” he said. The student-teacher ratio on weekdays is about 12:1, replicating a seminar-style atmosphere. Saturday and during the summer is 21:1. The average ratio in New York City public high schools, comparatively, is nearly 27:1.

Like many peers in the program, Acheampong will be a first-generation college student. His parents moved from Ghana to the U.S. when he was 4 years old “to provide me and my brother with a better life,” he said. Now, he’s an aspiring petroleum engineer — or dentist — and is in friendly competition with his older brother, who attends Brooklyn College.

“He never got a chance to go to SEO, so I have to be better than him,” Acheampong said, grinning. He added that he wants to be a role model for his 3-year-old brother. “I’m trying to make something of myself.”

Not everyone who applies to SEO Scholars gets in. The program receives about 1,200 complete applications a year, which include a student’s report card, a few short essays and income verification. About 23 percent secure a spot, rivaling acceptance rates at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Vassar College.

One of students’ critiques of the Scholars program is this selectivity — that the bar is set too high and risks overlooking other students in need. Program heads acknowledged that given the academic rigor and time commitment SEO demands, “we’re looking for kids who are motivated and have the aptitude to succeed.” That means at least a 70 GPA, which SEO’s Hau points out “is still quite low in the New York City school system.”

Prospective students “might not have been identified in ninth grade for certain advanced classes, [but] they’re not in danger of dropping out, so they’re just in the middle, being undereducated,” she said. “That’s really our target population.”

Alexander Rodriguez, 17, Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice

For Alexander Rodriguez, the program’s value extends well outside of the classroom.

Rodriguez knew early in high school that he wanted to pursue a medical career. But his downtown Brooklyn school didn’t offer physics, chemistry or biology, and he worried that he’d start off college in remedial courses.

In response, SEO connected Rodriguez to Weill Cornell Medicine’s Black & Latino Men in Medicine Initiative, allowing him to explore different medical career paths from surgery to osteopathic medicine his junior year.

“It was such an intensive introduction-to-medicine course that I just fell in love with,” Rodriguez said. “I got to do a lot of things that a lot of people can’t say they did, like do practice surgery on the da Vinci robot machine.”

As part of its summer enrichment programs, SEO Scholars also sent Rodriguez to India and Nepal for five weeks to learn about public health disparities — an opportunity he called “the most life-changing, mind-changing experience of my entire life.”

Like Acheampong, Rodriguez plans on becoming a first-generation college student. His mother grew up poor in the Dominican Republic, helping on the family farm after middle school. His father cared for his mother, who was ailing with cancer, working to help pay her medication bills.

Rodriguez’s own journey has sometimes been grueling. For two months junior year, he barely had a day off. SEO ran for eight hours on Saturdays, and from 1 to 4 p.m. on Sundays he would be at the medical program on the Upper East Side.

“Mental health days — I miss those,” Rodriguez said. “I think everyone wants to quit at some point because it’s just so hard, and it’s one of those things where you don’t see outcomes right away. … Everyone says, ‘Trust the process.’”

College junior Ivy Allotey has trusted the process for seven years. A psychology major at Columbia University with an interest in public service work, Allotey continues to lean on SEO for networking for internship opportunities, biweekly calls with her adviser, who is there to “talk about anything, from personal things to academics,” and résumé tinkering.

“I won’t go to [my college’s career center] as much for résumés or cover letters, because I don’t think they’d give me the same personalized support SEO does,” she said.

Allotey is considering moving to Ghana, where her family is from, to promote youth engagement in civil service. Knowing that she has a “solid network” behind her post-graduation makes the sunsetting of her time in SEO Scholars less “nerve-racking.” “It’s actually more reassuring for me,” she said.

While it’s “all love” for SEO, Rodriguez said it’s “devastating” to consider the reality that there are students outside of the program being left behind. He and other students interviewed all said they have friends who weren’t accepted — or who learned about the program too late to apply.

SEO officials say the organization conducts extensive outreach, visiting about 150 of the district’s more than 400 high schools a year and hosting a few meet-and-greets with students and parents. It also launches social media campaigns on Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat and enlists alumni to spread the word. Applications are typically due mid-December of each school year.

For students who don’t get in, SEO provides a referral list for alternate options, which include A Better Chance, Bottom Line, Minds Matter and LEDA Scholars.

Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye, 18, Brooklyn College Academy

Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye heard about SEO Scholars when program managers visited her school freshman year. She remembers taking a flier and mulling it over on the bus ride home to her Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood that day, realizing that this could be her chance.

On track to become the first person in her family to finish high school, she’d told herself, “I have no type of guidance [from my family], so for me to not take this opportunity is me telling myself, ‘I don’t want to graduate.'”

It hasn’t come without sacrifice. Ndiaye hasn’t visited her extended family in Senegal since 2008 — a trip she was hoping to make every summer of high school before SEO came into the picture. “I’ve forgotten a lot of my family members because I haven’t seen them in a long time,” she said.

Nevertheless, she’s fully embraced the program, largely because of its inclusive atmosphere and diverse teaching workforce. About 57 percent are teachers of color, compared with 42 percent citywide and about 20 percent statewide.

Students in SEO can call teachers by their first names. Class is always conducted in a circle, because there’s “no back row in SEO,” Ndiaye explained. A teacher will “compliment” a student’s do-rag instead of making him or her take it off. The literature also reflects the students themselves, who are majority black and Hispanic. The city’s DOE has expressly backed culturally responsive education, though equity advocates point out that 83 percent of books commonly used in the city’s public schools are still written by white authors.

“We have the representation that we need, and we have teachers that genuinely care for us and are motivated,” she said. “We have one-on-one check-ins as often as we want where we just sit with whoever and just talk to them about ourselves and our lives and what we’re going through, and they’ll talk to us about their lives too.”

“It’s like a family.”

All in this together

Sometimes, students get their greatest inspiration and support from each other.

Sixteen-year-old Mashiha Chowdhury feels she can “relate” more to her peers at SEO than those at Beacon High School, a selective college-preparatory school in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen where half of the students are white. Chowdhury’s family is from Bangladesh.

“It wasn’t easy to connect [with Beacon kids], but in SEO it was an automatic connection,” said Chowdhury, who commutes more than an hour each way to SEO Scholars from her home in the Bronx. While SEO operates independently of the school system, the DOE’s Office of Pupil Transportation provides MetroCards to cover students’ travel costs for weekday and Saturday classes.

Chowdhury said the program “created new bonds that I probably would not lose, and it made me realize, ‘OK, this is what I want in a friend, regardless of academics.’”

SEO students can commiserate about having to drag themselves out of bed on Saturdays and on weekdays during the summer. They’ve even created Snapchat groups to hold one another accountable.

“We call each other, keep each other going,” Chowdhury said. If a student is late, “we text, ‘Where are you?’ or call them.”

They say their shared passion and drive has made all the difference.

“We’re all in this together,” Acheampong said. “We all have to do it. So we might as well do it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)