Williams: Successful Community Schools — Like Those in NYC’s Rand Study — Are Compatible With Successful Education Reforms

How do you measure a successful education reform? The answer is thornier than you think.

You could start with the obvious — a successful reform must be one that improves students’ academic performance — but the path from challenge to solution isn’t so simple. Academic improvements don’t happen in a vacuum. They can’t be hammered into existence solely on the strength of educators’ wills.

Students arrive at school amid broader socioeconomic, racial and familial contexts. These often shape the opportunities students receive — and how they engage with those. There’s ample debate about how much education reforms can achieve without engaging directly with out-of-school factors.

That’s where community schools come in. They look to resolve the debate by blurring the lines between education reforms and anti-poverty efforts. They provide a range of health, mental health and family support services aimed at addressing issues that can impede student learning. Many of these schools partner with community organizations to engage some of the difficult realities imposed on children growing up in poverty.

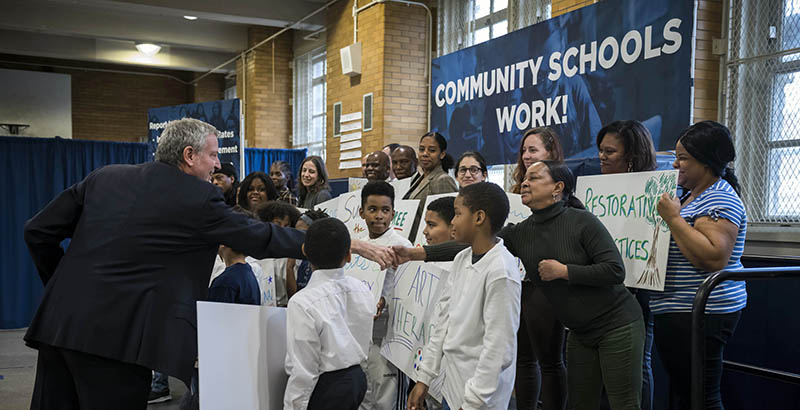

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio has presented the wraparound services offered by the city’s Community Schools program as an alternative approach to other recent education reforms — things like school accountability policies linked to academic assessments and systemic overhauls of how schools operate. In essence, instead of reforming schools, this approach aims to shift the contexts in which schools operate.

Does it work, as an education reform? This week, a new study of the city’s Community Schools program provided an answer. Researchers from the RAND Corporation found that NYC’s Community Schools raised students’ attendance and grade progression rates. High school students at Community Schools picked up more credits, and elementary and middle school students had fewer disciplinary incidents.

That’s a pretty solid haul for the $195 million program and its 267 schools. And yet, the study also found limited academic improvements — no increase in student reading scores and an increase in math scores in only one year of the three-year study period.

So, does that count as a successful education reform? It all depends on the terms you set. Critics of the program note that this sort of finding — some general improvements in school climate and non-academic behaviors but limited impacts on academic achievement — is relatively common. For instance, one 2017 study found that an intensive community schools program helped get students more support but “did not have a positive effect on students’ attendance, academic performance, or behavior after two years.”

These critics are not wholly wrong. Proxies like attendance rates and credit accumulation aren’t the core objectives of public education. We don’t run schools to ensure that kids attend at higher rates or get more credits or — even — get a graduation credential. We run schools so that kids who attend learn skills and acquire knowledge. The credits and diplomas are just formal ways of representing that learning to the world. So it’s hard to celebrate an education reform that improves proxy metrics but not actual learning.

But that critique also misses the point. Put simply, we shouldn’t justify providing vision care and mental health therapy to children from low-income families on the grounds that these will improve their math scores or reading levels. Anti-poverty efforts and social services ought to be judged on their own terms: Are community schools’ dental programs improving children’s oral health? Are their mentorship and mental health programs improving children’s well-being? These are basic services that all children deserve as developing humans and that policymakers in New York City and the broader United States — there are more than 5,000 community schools throughout the country — ought to be able to provide.

This confusion is the natural consequence of conflating wraparound services and anti-poverty efforts with education reform initiatives. It invites misunderstanding about what these services are actually for. Pitching programs like community schools as alternatives to education reforms makes it hard to decide if community schools work. Incidentally, it’s also possible to make this same rhetorical mistake, but in reverse. For instance, it’s equally wrong to pan efforts to improve public education because they haven’t solved economic inequality or structural racism. School reforms aim to make schools more equitable, and that’s the standard we should use to judge them.

It’s an argument as old as the Coleman Report: Can we fix schools without fixing poverty? Can we address poverty without addressing educational inequities? Fortunately, studies like RAND’s suggest something so straightforward that asserting it borders on obnoxious: Programs to address educational inequities are wholly compatible with anti-poverty programs. New community school models don’t relieve us of responsibility to reform how those schools serve historically underserved children, just as efforts to reform those schools don’t relieve us from the responsibility to address poverty’s impact on those children.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)