‘We Don’t Have Any Talented Students’: Confronting English Language Learners’ Drastic Under-Representation in Elementary Gifted & Talented

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

English language learners are drastically under-represented in the nation’s gifted and talented elementary education programs. And the one tool advocates hoped would better identify them — non-verbal assessments — hasn’t worked, critics say.

Experts say teachers have not been adequately trained to spot these students’ gifts and that schools’ failure to recognize and grow their talent could turn them off to school entirely.

Educators’ increased focus on English language learners comes as school districts around the nation reassess their elementary gifted and talented offerings after New York City’s program was threatened with closure by the outgoing mayor for its failure to include Black and Hispanic students. The program won a reprieve, though concerns about equity will likely remain.

Immigrant advocates in New York and elsewhere say English language learners’ exclusion marks a major loss not only for those who have been shut out, but for their families, communities and the nation at large.

While advanced programs at the elementary level are dubious — most have not prompted major long-term academic gains — a student’s selection signals to schools, parents and the child that they have special gifts, boosting their confidence and exposing them to advanced materials.

Carly Spina, who taught English language learners inside Glenview School District 34 near Chicago for 15 years, said that in some cases, a child’s participation in gifted programming in their elementary years is a prerequisite for their enrollment in advanced courses in higher grades.

“It’s all about access,” said Spina, who now works with educators who serve these children statewide. “Our students deserve to be there.”

And it’s more than an ethical issue: It’s a legal obligation.

Kristina Moon, senior attorney with the Education Law Center, said English language learners have the right to equal opportunity in all school programs.

“They cannot be excluded … just because they are not proficient in the English language,” she said, citing the federal Equal Educational Opportunities Act.

Those concerned about these students’ overlooked abilities are re-evaluating their methods.

Jonathan Plucker, president of the National Association for Gifted Children, said schools around the country are beginning to abandon costly non-verbal gifted assessments for English language learners because they yield the same results as traditional verbal tests.

“We cannot figure out why that is the case,” Plucker said. “These districts are finding it’s expensive and they aren’t getting different data. For the life of us, we never expected that.”

‘We don’t have any talented students’

English language learners represented more than 10 percent of students nationwide in 2018 according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Yet they accounted for just 2.4 percent of the nation’s 3.3 million gifted children that same year, the last for which such data is available, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

While the data alone do not prove discriminatory conduct, the civil rights office said in a statement, members of the public who believe these students are being unfairly excluded are invited to file a complaint on their behalf.

A survey by The 74 of school districts across the country reflects the national disparity. While some managed to include a proportionate — or nearly proportionate — number of non-English speaking students in gifted programming, most included only a fraction of these children.

English language learners accounted for 18 percent of the student body in the Broward County Public Schools in Florida, but make up only 1.5 percent — just 39 of 2,607 children — in its gifted elementary program.

Other districts, including those in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and Florida’s Palm Beach, Brevard and Miami-Dade counties, report similar statistics.

Educators who work with gifted students are taking note and trying to make change.

Their efforts coincide with a massive uptick in newcomer children crossing the nation’s southern border now that immigration and pandemic-related restrictions have eased.

These students face numerous hurdles upon arrival: Educators often underestimate their intelligence and ability, working under the false assumption that they are somehow deficient or in need of remediation.

What schools fail to realize, experts say, is that many of these children have already mastered multiple languages in their home countries, a reflection of their acumen.

“It is not rare for me to talk to a principal who says, ‘All of this is really important,’” Plucker said. “‘And I say, ‘What can we do to help you with your school?’ And they say, ‘Oh, we only have low-income Hispanic kids here. We don’t have any talented students.’”

Part of the reason for this, experts say, is schools’ overreliance on test scores as a means to assess student’s ability.

English language learners often score low on state and other exams, but for some, it’s language, not a lack of brainpower, that holds them back. Experts say a child who earns low marks might still be gifted, but their skills need to be identified in other ways.

“We have all of this talent just sitting there,” Plucker said. “And the child isn’t benefiting from their own skills. That is a massive societal failure. We simply have to do better.”

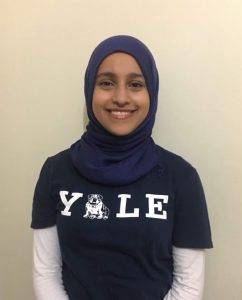

Amal Altareb, 20, knows what it’s like to struggle with a new language. She arrived in the United States from Yemen at age 11 unable to speak English. Determined to learn — she was a gifted student back home — she spent hours each night translating her assignments.

“I pulled so many all-nighters,” said Altareb, who attended school in Memphis, Tennessee. “I was not giving myself any mercy.”

While some educators failed to recognize her abilities — her math teacher openly laughed at her homework because she so badly misinterpreted the instructions, she said — her English as a Second Language instructor, who spoke her native Arabic, knew she was gifted.

“I have so much gratitude for him,” she said. “I would ask him questions from the beginning of the class until the end.”

Altareb scored high enough on her end-of-year math and science assessments to be placed in gifted classes the following year. She was even permitted to study Russian even though she had not yet fully mastered English, a reflection, she said, of her principal’s faith in her abilities.

“People believed in me after I proved myself,” she said.

The teen enrolled in college-level Advanced Placement courses in high school and went on to become valedictorian.

She is now a political science major at Yale University.

New, non-verbal tests use animation

There are only 137 English language learners in Prince George’s County Maryland’s gifted and talented program in grades 2-12, comprising less than 1 percent of the 11,560 participating students. Non-English speaking children make up 19.7 percent of the overall student population.

Theresa Jackson, the district’s supervisor of talented and gifted programs, said an additional 1,469 participants are former English language learners who have tested out of the program. Still, she said, their linguistic ability is typically not on-par with native English speakers.

Jackson said, too, that her school system is always striving to increase identification of historically underrepresented populations, including those students who receive free and reduced-priced meals, an indicator of poverty, in addition to Hispanic students and those who receive special education services.

“I am not sure I will ever be fully happy, but we are inclusive of all sub-groups,” she said.

In Palm Beach County, Florida, just 1.9 percent or 84 children of 4,519 gifted and talented students were English language learners. Yet these children comprise more than 23 percent of the district’s elementary school population. The figures include the district’s 49 charter schools.

Walter G. Secada, vice dean of the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Miami, said many educators believe a child’s English must improve before they are identified as gifted.

But that’s untrue, he said, adding the narrative only serves as an excuse for teachers not to look for talent in this group.

“It locates the problem within the child and not in our delivery system,” he said.

Experts say schools’ role as gatekeepers to advanced learning can be problematic: Many campuses rely on teacher and parent referrals to identify gifted children, both of which lead to the exclusion of those just learning English.

Kathy Escamilla, interim executive director of the BUENO Center for Multicultural Education at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said newcomer families face unique challenges in communicating with their local schools and are often reluctant to push back, not wanting to seem disrespectful.

“Non-English speaking parents aren’t going to go to school and say, ‘I think my kid is gifted,’” she said. “They are much too humble and rely on the school to do those kinds of things.”

Spina, of Illinois, said some parents are required to write a letter explaining their position and win the support of other teachers, a difficult task for families who do not speak English.

The longtime teacher, has, in some cases, informed parents of their legal rights, helped them write rebuttals, accompanied them to meetings with school administrators and worked to make sure translation services were available.

“We have to embrace our space as change agents,” Spina said. “We have to advocate. If we are not fighting for them, we are not walking our walk here.”

English language learners’ exclusion from gifted programming is a long-standing but not unsolvable problem. Escamilla said schools can use high quality non-verbal assessments — some have just been released — and better train staff to assess non-English speaking students through observation.

They can also use tests written in the child’s native language, she said.

Jack Naglieri, a psychologist and research professor at the University of Virginia, created one of the most widely used tests for assessing the ability of non-English speaking children.

He’s recently developed a new exam for this purpose, the first of its kind to use animation.

“There is no doubt in my mind we will find more children who do not speak English doing well on these tests,” he said.

Quick to understand cultural norms

Marcy Voss of Kerrville, Texas, has spent more than 35 years working with or on behalf of gifted and bilingual children either as a teacher or an administrator. Like Plucker, she and Escamilla are aware of the shortcomings of non-verbal tests.

Voss said educators should look at a portfolio of work — not a single test score — in order to identify advanced English language learners.

Voss said, too, these students should not be evaluated based on what they already know: Some have missed years of school in their home countries and simply didn’t have the opportunity to learn.

She and many other immigrant advocates believe these children should be evaluated based on how well they comprehend new material — an approach some administrators have been slow to embrace.

“There are gifted students in this population,” she said. “I’ve seen them and they deserve to have their educational needs met.”

Whenever Voss is tasked with identifying a gifted child, she tries to understand the way their mind works, how quickly they catch on to new concepts and their ability to solve problems, she said.

With non-English speakers, she considers a number of additional factors, including how fast they learn the language.

Gifted English language learners might also adapt more easily to their new environment as compared to other newcomers — they might be quick to understand the cultural norms and nuances of their newly adopted country — act as ambassadors for other students and their own parents, all of which reflects their ability to make connections quickly, she said.

“They understand the hidden rules of order without having them explained,” said Voss, who facilitates the Emerging Leaders Program for the Texas Association for the Gifted & Talented.

But even after they gain admission to advanced programming, English language learners can face nearly insurmountable obstacles: Many teachers of gifted and talented students don’t feel they need to make language accommodations for non-English speaking participants, Spina said.

Spina is sensitive to teachers’ time and workload, but will challenge those who shirk this responsibility, telling them, “You don’t get to opt out.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)